First. That these loans should only be made at a very high rate of interest. This will operate as a heavy fine on unreasonable timidity, and will prevent the greatest number of applications by persons who do not require it. The rate should be raised early in the panic, so that the fine may be paid early; that no one may borrow out of idle precaution without paying well for it; that the Banking reserve may be protected as far as possible.

Secondly. That at this rate these advances should be made on all good banking securities, and as largely as the public ask for them. The reason is plain. The object is to stay alarm, and nothing therefore should be done to cause alarm. But the way to cause alarm is to refuse some one who has good security to offer… No advances indeed need be made by which the Bank will ultimately lose. The amount of bad business in commercial countries is an infinitesimally small fraction of the whole business…

The great majority, the majority to be protected, are the ‘sound’ people, the people who have good security to offer. If it is known that the Bank of England is freely advancing on what in ordinary times is reckoned a good security—on what is then commonly pledged and easily convertible—the alarm of the solvent merchants and bankers will be stayed. But if securities, really good and usually convertible, are refused by the Bank, the alarm will not abate, the other loans made will fail in obtaining their end, and the panic will become worse and worse.

Walter Bagehot Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market (1873).

The classical theory of the lender of last resort stressed

(1) protecting the aggregate money stock, not individual institutions,

(2) letting insolvent institutions fail,

(3) accommodating sound but temporarily illiquid institutions only,

(4) charging penalty rates,

(5) requiring good collateral, and

(6) preannouncing these conditions in advance of crises so as to remove uncertainty.

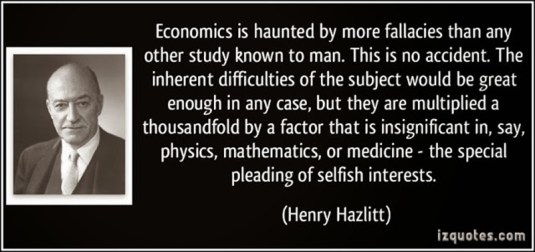

Did anyone follow these rules in the global financial crisis? The Fed violated the classical model in at least seven ways:

- Emphasis on Credit (Loans) as Opposed to Money

- Taking Junk Collateral

- Charging Subsidy Rates

- Rescuing Insolvent Firms Too Big and Interconnected to Fail

- Extension of Loan Repayment Deadlines

- No Pre-announced Commitment

- No Clear Exit Strategy

…{the Fed’s} policies are hardly benign, and that extension of central bank assistance to insolvent too-big-to-fail firms at below-market rates on junk-bond collateral may, besides the uncertainty, inefficiency, and moral hazard it generates, bring losses to the Fed and the taxpayer, all without compensating benefits. Worse still, it is a probable prelude to a severe inflation and to future crises dwarfing the current one.

Recent Comments