General government expenditure as % of US, British and Canadian GDP since 1960

28 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, fiscal policy, macroeconomics, politics - USA, public economics Tags: British economy, Canada, growth of government, Margaret Thatcher, size of government, Thatchernomics, Tony Blair

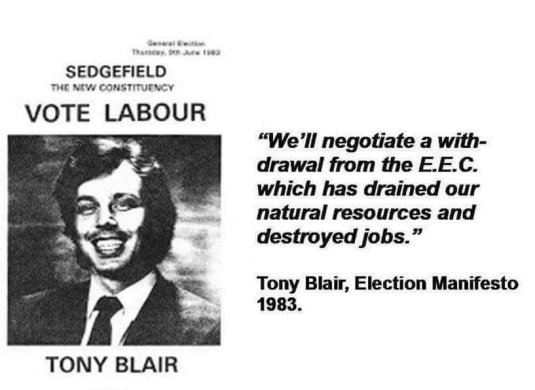

Both the British and Canadian economies experienced major winding backs in the size of government. Only the UK, under neoliberal pawn and closet Thatcherite Tony Blair, was that undone. He is now despised by many Labour Party members including its current leader for this record.

Data extracted on 23 Feb 2016 07:45 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

Did the British disease pass retirees by? British retiree and non-retiree median real household income by Prime Minister since 1977

03 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic growth, economic history, macroeconomics, poverty and inequality Tags: British economy, British politics, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair

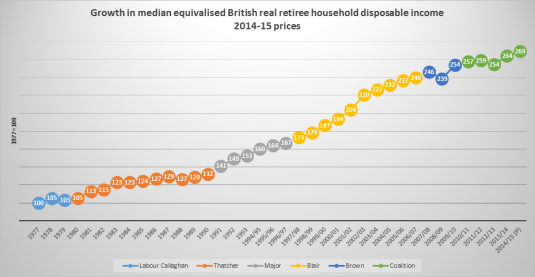

The British disease and the horrors of Thatchernomics past British retirees by as did pretty much the Global Financial Crisis. Slow and steady as she goes under every Prime Minister since 1977 has been year in year out result for the real disposable median incomes of British retired households. Despite it all, British retiree household incomes increased by 170% since the winter of discontent. The fastest growth in retiree incomes was under Tony Blair.

Source: Release Edition Reference Tables – ONS.

Notes:

1 Households are ranked by their equivalised disposable incomes, using the modified-OECD scale.

2 1994/95 represents the financial year ending 1995, and similarly through to 2014/15, which represents the financial year ending 2015.

3 Income figures have been deflated to 2014/15 prices using an implied deflator for the household sector.

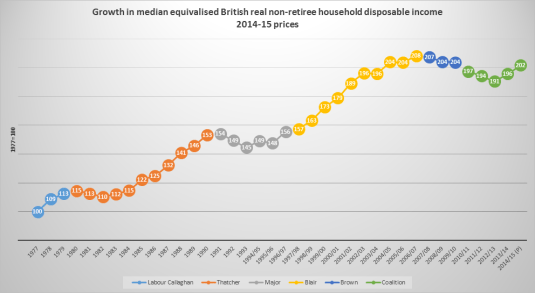

It has been a much rockier ride for British households yet to retire. Once again, the only time a sustained real income increases for non-retired households was under Thatcher and Blair. Despite it all, household real incomes have doubled since the winter of discontent. The majority of that doubling was under the dead hand of Tony Blair. British Labour now spends a considerable amount of time repudiating that time of unusually rapid household income growth across all of British society.

Source: Release Edition Reference Tables – ONS.

Notes:

1 Households are ranked by their equivalised disposable incomes, using the modified-OECD scale.

2 1994/95 represents the financial year ending 1995, and similarly through to 2014/15, which represents the financial year ending 2015.

3 Income figures have been deflated to 2014/15 prices using an implied deflator for the household sector.

@jeremycorbyn incomes of the poorest increased most under Blairism @UKLabour

13 Sep 2015 2 Comments

in economic history, labour economics, Marxist economics, poverty and inequality Tags: British economy, Leftover Left, Tony Blair, Trish Labor Party, welfare state

Under Tony Blair the incomes of the UK's poorest families increased by more than under any other Prime Minister. http://t.co/8Uh8GBqbRB—

Tom Forth (@thomasforth) September 12, 2015

Labour is incoherent & self-defeating in its opposition to private prisons

21 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of crime, industrial organisation, law and economics, managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, survivor principle Tags: creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness, evidence-based policy, Leftover Left, New Zealand Labour Party, prison privatisation, private ownership, private prisons, privatisation, state ownership, Tony Blair

The New Zealand Labour Party would make a lot more progress in its opposition to private prisons if it would drop its ideologically blinkered opposition to privatisation. If it was to do that, it would have a much stronger case against private prisons.

That case would be based on the modern economics of industrial organisation and state and private ownership. In particular, the make or buy decision that any organisation, be they public or private must face when deciding whether to make a particular production input in-house or source it externally.

Labour’s current case against private prisons is a bunch of ideological clichés as it illustrated today in a post on Facebook by Jacinda Ardern. Her post was based on her speech in the House of Representatives:

Yes, part of that opposition is my view that no one should make a profit from incarceration, but it’s also about the complete fallacy that somehow a company like SERCO will do the job better.

The notion that no one should make a profit from incarceration is farcical. There are a whole range of private profit making suppliers of goods and services to prisons and prison officers draw a wage.

The case was state ownership, as well stated by Andrei Shleifer is no different than any other ownership decision taken by an organisation facing the inability to contract fully over hard to measure quality issues with the goods or services supplied to it.

Shleifer in “State versus Private Ownership” argues that you make in-house rather than buy in the market under the following conditions:

- opportunities for cost reductions that lead to non-contractible deterioration of quality are significant;

- innovation is relatively unimportant;

- competition is weak and consumer choice is ineffective; and,

- reputational mechanisms are also weak.

What particularly should focus Labour’s attention on Andrei Shleifer’s State versus Private Ownership is it is a simplified version of Hart, Oliver, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W Vishny. 1997. “The Proper Scope of Government: Theory and an Application to Prisons.” Quarterly Journal of Economics. The abstract to that longer paper says the following:

When should a government provide a service in-house, and when should it contract out provision? We develop a model in which the provider can invest in improving the quality of service or reducing cost.

If contracts are incomplete, the private provider has a stronger incentive to engage in both quality improvement and cost reduction than a government employee has. However, the private contractor’s incentive to engage in cost reduction is typically too strong because he ignores the adverse effect on non-contractible quality. The model is applied to understanding the costs and benefits of prison privatization.

The privatisation of prisons is at the margin of the case was state versus private provision of a good or service.

Labour forecloses this entire literature to itself and bases its arguments on ideology. Any other argument Labour makes are just talking points to a fixed ideological position.There is no give-and-take. When one argument is knocked down, Labour just looks for other arguments to defend the same fixed position.

The reason Labour forecloses this large economic literature on state versus private ownership and its application to private versus public prisons is embracing that literature would mean admitting that same literature makes a strong case for the privatisation of a number of other government services and state-owned enterprises. As Shleifer says in State versus Private Ownership:

Private ownership should generally be preferred to public ownership when the incentives to innovate and to contain costs must be strong.

The main argument, the best argument, against the privatisation of publicly provided services and state-owned enterprises is the dilution of quality once it is supplied privately. This risk of compromises and quality to enhance profits is higher when the privatisation is contracting back to government. Detailed contracts must be written to assure quality. As Hart, Shleifer and Vishny say:

Critics of private schools fear that such schools, even if paid for by the government (e.g., through vouchers), would find ways to reject expensive-to-educate children, who have learning or behavioural problems, without violating the letter of their contracts. Critics also worry that private schools would replace expensive teachers with cheaper teachers’ aides, thereby jeopardizing the quality of education.

In the discussion of public versus private health care, the pervasive concern is that private hospitals would find ways to save money by shirking on the quality of care or rejecting the extremely sick and expensive-to-treat patients. In the case of prisons, concern that private providers hire unqualified guards to save costs, thereby undermining safety and security of prisoners, is a key objection to privatization.

Our model tries to explain both why private contracting is generally cheaper, and why in some cases it may deliver a higher, while in others a lower, quality level than in-house provision by the government.

By basing the argument on the strengths and weaknesses of contracting over quality for specific services, Labour would have to drop its straight ideological opposition to privatisation and run on a case-by-case basis over the ability to successfully contract to assure quality.

That sounds far too much like becoming a Blairite – the horror, the horror if you are a Labour Party member in the 21st century concerned more about ideological purity than winning office and improving the lot of the people claim to you represent.

If it were to embrace the modern economics of state versus private ownership, Labour would have to agree with Hart, Shleifer and Vishny when they say:

the case for privatization is stronger when quality reducing cost reductions can be controlled through contract or competition, when quality innovations are important, and when patronage and powerful unions are a severe problem inside the government.

When the government cannot fully anticipate, describe, stipulate, regulate and enforce exactly what it wants and prisons are a good case this and has difficulty enforce in any contract with regard to quality assurance, it’s better to make it in-house as Hart, Shleifer and Vishny show.

A call to the barricades is not be very uplifting if based on incomplete contracting over service quality rather than the evils of capitalist profit. It is unfortunate that the Labour Party sacrifice the interests of those incarcerated in the prison system to its unwillingness to be denounced as a Blairite.

The case for private prisons is based on public prisons may have fewer incentives to keep costs down, including keeping costs down by skimming on quality to increase profits as Andre Shleifer explains:

Ironically, the government sometimes becomes the efficient producer precisely because its employees are not motivated to find ways of holding costs down.

The modern case for government ownership can often be seen from precisely this perspective. Advocates of such ownership want to have state prisons so as to avoid untrained low-wage guards, state water utilities to force investment in purification, and state car makers to make them invest in environmentally friendly products.

As it turns out, however, this case for state ownership must be made carefully, and even in most of the situations where cost reduction has adverse consequences for non-contractible quality, private ownership is still superior.

That is the twist in the tale for Labour. The case against privatisation is merely a balancing act requiring detailed scrutiny of the potential to successfully enforce contracts with private providers over quality assurance.

The case against prison privatisation is simply for the public sector as fewer incentives to weaken quality because this increases the bottom line of the contractor or salaries of management. It’s a trade-off between cost control and quality dilution. Publicly run prisons have fewer incentives to control costs, but they also have fewer incentives to deliberately cut corners on quality to increase dividends or managerial salaries .

There’s nothing new about the non-profit provision of goods and services in the marketplace. A whole range of non-profit firms emerged through market competition in situations where contracting over quality or trust was costly.

Most life insurance companies were initially mutually owned by customers. Because they were a non-profit firm, there were fewer avenues to run off with the premiums through excessive dividends.

Many private universities and private schools are run by charitable trusts as a way of quality assurance. Another way of quality assurance is heavy involvement of alumni through giving and sports to police the reputation of the university or school they once attended or want their children to attend.

An arguable case can be made against prison privatisation, based on sound economic principles as long as you’re willing to admit that in many cases privatisation is a good idea based on the same economic principles. That’s a bridge too far from the Labour Party in New Zealand.

Maybe the reason is Labour knows that although they may be able to make an arguable case against prisons privatisation, they may still lose to better arguments and, in particular, successful experiments in prison privatisation at home and abroad. Better to keep the debate away from evidence-based policy. This awkwardness in seeking out the best argument is due to the proclivity of Labour in opposition to repudiate the successes of its last time in office and look for reasons to make themselves even less electable by going left rather than going back into the centre.

UK labour has gone one up from the credit card pledges

04 May 2015 Leave a comment

in Public Choice Tags: British general election, Tony Blair, UK politics

Ed Miliband's stone slab. Labour says will be put up in Downing St garden if they win http://t.co/sQ44clVtYq—

lucy manning (@lucymanning) May 03, 2015

In a great irony, the stone monolith in the garden of No. 10 may not get local council planning permission, and more importantly, permission to alter an historic building from Historic England.

Recent Comments