POSNER, Circuit Judge, with whom EASTERBROOK, Circuit Judge, joins in 819 F. 2d 732 – Chicago Board of Realtors Inc v. City of Chicago:

The stated purpose of the ordinance is to promote public health, safety, and welfare and the quality of housing in Chicago. It is unlikely that this is the real purpose, and it is not the likely effect.

Forbidding landlords to charge interest at market rates on late payment of rent could hardly be thought calculated to improve the health, safety, and welfare of Chicagoans or to improve the quality of the housing stock.

But it may have the opposite effect. The initial consequence of the rule will be to reduce the resources that landlords devote to improving the quality of housing, by making the provision of rental housing more costly. Landlords will try to offset the higher cost (in time value of money, less predictable cash flow, and, probably, higher rate of default) by raising rents. To the extent they succeed, tenants will be worse off, or at least no better off.

Landlords will also screen applicants more carefully, because the cost of renting to a deadbeat will now be higher; so marginal tenants will find it harder to persuade landlords to rent to them. Those who do find apartments but then are slow to pay will be subsidized by responsible tenants (some of them marginal too), who will be paying higher rents, assuming the landlord cannot determine in advance who is likely to pay rent on time. Insofar as these efforts to offset the ordinance fail, the cost of rental housing will be higher to landlords and therefore less will be supplied–more of the existing stock than would otherwise be the case will be converted to condominia and cooperatives and less rental housing will be built…

The provisions that authorize rent withholding, whether directly or by subtracting repair costs, may seem more closely related to the stated objectives of the ordinance; but the relation is tenuous. The right to withhold rent is not limited to cases of hazardous or unhealthy conditions. And any benefits in safer or healthier housing from exercise of the right are likely to be offset by the higher costs to landlords, resulting in higher rents and less rental housing.

The ordinance is not in the interest of poor people. As is frequently the case with legislation ostensibly designed to promote the welfare of the poor, the principal beneficiaries will be middle-class people.

They will be people who buy rather than rent housing (the conversion of rental to owner housing will reduce the price of the latter by increasing its supply); people willing to pay a higher rental for better-quality housing; and (a largely overlapping group) more affluent tenants, who will become more attractive to landlords because such tenants are less likely to be late with the rent or to abuse the right of withholding rent–a right that is more attractive, the poorer the tenant. The losers from the ordinance will be some landlords, some out-of-state banks, the poorest class of tenants, and future tenants.

The landlords are few in number (once owner-occupied rental housing is excluded–and the ordinance excludes it). Out-of-staters can’t vote in Chicago elections. Poor people in our society don’t vote as often as the affluent. See Filer, An Economic Theory of Voter Turnout 81 (Ph.D. thesis, Dept. of Econ., Univ. of Chi., Dec. 1977); Statistical Abstract of the U.S., 1982-83, at pp. 492-93 (tabs. 805, 806). And future tenants are a diffuse and largely unknown class.

In contrast, the beneficiaries of the ordinance are the most influential group in the city’s population. So the politics of the ordinance are plain enough, cf. DeCanio, Rent Control Voting Patterns,Popular Views, and Group Interests, in Resolving the Housing Crisis 301, 311-12 (Johnson ed. 1982), and they have nothing to do with either improving the allocation of resources to housing or bringing about a more equal distribution of income and wealth.

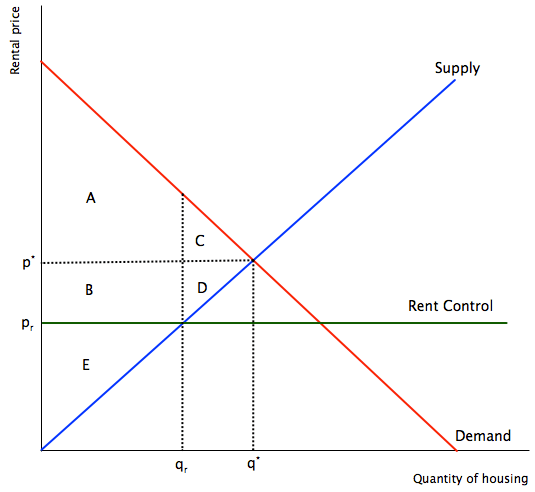

A growing body of empirical literature deals with the effects of governmental regulation of the market for rental housing. The regulations that have been studied, such as rent control in New York City and Los Angeles, are not identical to the new Chicago ordinance, though some–regulations which require that rental housing be "habitable"–are close. The significance of this literature is not in proving that the Chicago ordinance is unsound, but in showing that the market for rental housing behaves as economic theory predicts: if price is artificially depressed, or the costs of landlords artificially increased, supply falls and many tenants, usually the poorer and the newer tenants, are hurt…

Apr 20, 2023 @ 14:07:25

Your graphic is wrong. Rent control doesn’t keep the rent price flat (the green line), it just prevent “parasite blood sucker landlords” to pump the rent price by 40%.

LikeLike