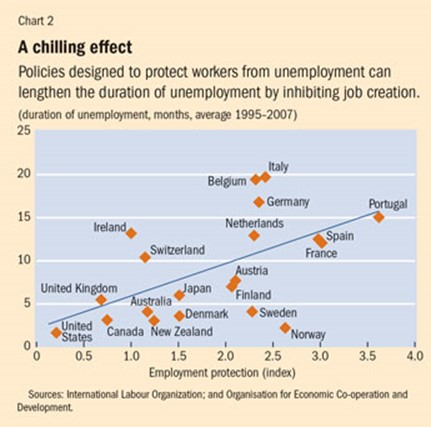

As discussed yesterday, if the Employment Court had its way, New Zealand case law under the Employment Relations Act regarding redundancies and layoffs would be as job destroying as those in France.

The Employment Court’s war against jobs goes back more than 20 years. To 1991 and G N Hale & Son Ltd v Wellington etc Caretakers etc IUW where the Court held that a redundancy to be justifiable under law it must be ‘unavoidable’, as in redundancies could only arise where the employer’s capacity for business survival was threatened.

The Court of Appeal slapped that down and affirm the right of the employer to manage his business in no uncertain terms:

…this Court must now make it clear that an employer is entitled to make his business more efficient, as for example by automation, abandonment of unprofitable activities, re-organisation or other cost-saving steps, no matter whether or not the business would otherwise go to the wall…

The personal grievance provisions … should not be treated as derogating from the rights of employers to make management decisions genuinely on such grounds. Nor could it be right for the Labour Court to substitute its own opinion as to the wisdom or the expediency of the employer’s decision.

When a dismissal is based on redundancy, it is the good faith of that basis and the fairness of the procedure followed that may fall to be examined on a complaint of unjustifiable dismissal

… the Court and the grievance committees cannot properly be concerned with an examination of the employer’s accounts except in so far as it bears on the true reason for dismissal.

The Employment Court could only inquire as to the genuineness of the employer’s decision and the procedures adopted. The Court could not substitute their views on management decisions. No second-guessing.

In Brake v Grace Team Accounting Ltd, the Employment Court found its way back into second-guessing employer’s decisions about how to manage their business. The figures used by the employer to decide that a redundancy was required were in error. The employer miscalculated.

The Employment Court had previously held in Rittson-Thomas T/A Totara Hills Farm v Hamish Davidson that the statutory test of what a fair and reasonable employer could have done in all the circumstances applies to the substantive reasoning for redundancies. Some enquiry into the employer’s substantive decision is required to establish that a hypothetical fair and reasonable employer could also make the same decision in all of the circumstances.

Subsequently in Brake v Grace Team Accounting Ltd, the Employment Court found that the actions by the employer were “not what a fair and reasonable employer would have done in all the circumstances” and “failed to discharge the burden of showing that the plaintiff’s dismissal for redundancy was justified”.

The Court found that the redundancy was “a genuine, but mistaken, dismissal”, but it still found that the dismissal was substantively unjustified. That is a major new development. Mistaken dismissals that are genuine are unlawful and grounds for compensation under the employment law.

The case was appealed where the issues were whether the correct test had been applied. The Court of Appeal, in a sad day for employers, job creation and the unemployed, found that the Employment Court was within its rights to do what it did and applied the statutory tests correctly:

GTA acted precipitously and did not exercise proper care in its evaluation of its business situation and it made its decision about Ms Brake’s redundancy on a false premise.

So it never turned its mind to what its proper business needs were but rather proceeded to evaluate its options based on incorrect information. We can see no error in the finding by the Employment Court that a fair and reasonable employer would not do this.

The test is now that fair and reasonable employers in New Zealand do not make mistakes. A much greater burden is now laid upon employers to show that not only that redundancies are justified, but they have made careful calculations and no mistakes.

No more seat of your pants entrepreneurship in New Zealand. No more entrepreneurial hunches – the essence of entrepreneurship is acting on hunches and other judgements that are incapable of being articulated to others and about which there is mighty disagreement in many cases. As Lavoie (1991) states:

…most acts of entrepreneurship are not like an isolated individual finding things on beaches; they require efforts of the creative imagination, skillful judgments of future costs and revenue possibilities, and an ability to read the significance of complex social situations.

The essence of entrepreneurship is your hunches are better than the next guy’s and you survive in competition by backing that hunch often to the consternation of the crowd. As Mises explains:

[Economics] also calls entrepreneurs those who are especially eager to profit from adjusting production to the expected changes in conditions, those who have more initiative, more venturesomeness, and a quicker eye than the crowd, the pushing and promoting pioneers of economic improvement…

The entrepreneurial idea that carries on and brings profits is precisely that idea which did not occur to the majority… The prize goes only to those dissenters who do not let themselves be misled by the errors accepted by the multitude

In many cases, those entrepreneurial hunches are sorted, sifted and selected on the basis of trial and error in the marketplace. Central to Hayek’s conception of the meaning of competition is it is a process of trial and error with many errors:

Although the result would, of course, within fairly wide margins be indeterminate, the market would still bring about a set of prices at which each commodity sold just cheap enough to outbid its potential close substitutes — and this in itself is no small thing when we consider the insurmountable difficulties of discovering even such a system of prices by any other method except that of trial and error in the market, with the individual participants gradually learning the relevant circumstances.

Remember Hayek’s conception of competition as a discovery procedure where prices and production emerge through the clash of entrepreneurial judgements and competitive rivalry:

…competition is important only because and insofar as its outcomes are unpredictable and on the whole different from those that anyone would have been able to consciously strive for; and that its salutary effects must manifest themselves by frustrating certain intentions and disappointing certain expectations

Errors are no longer permitted in the New Zealand labour market by the Employment Court. The Court has outlawed error in redundancy decisions.

This is despite the fact that the conception by Kirzner of the market process is that it is an error correction procedure without rival and a central role of entrepreneurial alertness is to correct errors in pricing and production:

It is important to notice the role played in this process of market discovery by pure entrepreneurial profit. Pure profit opportunities emerge continually as errors are made by market participants in a changing world. The inevitably fleeting character of these opportunities arises from the powerful market tendency for entrepreneurs to notice, exploit, and then eliminate these pure price differentials.

The paradox of pure profit opportunities is precisely that they are at the same time both continually emerging and yet continually disappearing. It is this incessant process of the creation and the destruction of opportunities for pure profit that makes up the discovery procedure of the market. It is this process that keeps entrepreneurs reasonably abreast of changes in consumer preferences, in available technologies, and in resource availabilities.

Rothbard made similar arguments about the centrality of discrepancies and error in entrepreneurship:

The capitalist-entrepreneur buys factors or factor services in the present; his product must be sold in the future. He is always on the alert, then, for discrepancies, for areas where he can earn more than the going rate of interest.

In Frank Knight’s conception of profit, there were temporary profits that arise from the correction of error:

In the theory of competition, all adjustments “tend” to be made correctly, through the correction of errors on the basis of experience, and pure profit accordingly tends to be temporary.

The Employment Court misunderstands the market process as a process of error correction. Those errors are identified through entrepreneurial alertness and trial and error. These errors are both of over-optimism and over-pessimism as Kirzner explains:

Errors of over-pessimism are those in which superior opportunities have been overlooked. They manifest themselves in the emergence of more than one price for a product which these resources can create. They generate pure profit opportunities which attract entrepreneurs who, by grasping them, correct these over-pessimistic errors.

The other kind of error, error due to over-optimism, has a different source and plays a different role in the entrepreneurial discovery process. Over-optimistic error occurs when a market participant expects to be able to complete a plan which cannot, in fact, be completed.

A considerable part of entrepreneurial alertness arises from the business opportunities created by sheer ignorance and pure error as Kirzner explains:

What distinguishes discovery (relevant to hitherto unknown profit opportunities) from successful search (relevant to the deliberate production of information which one knew one had lacked) is that the former (unlike the latter) involves that surprise which accompanies the realization that one had overlooked something in fact readily available. (“It was under my very nose!”)

The market process is a selection procedure where the more efficient survive for reasons that may be unknown to the entrepreneurs directly concerned as well as to observers and officious judges. Alchian pointed out the evolutionary struggle for survival in the face of market competition ensured that only the profit maximising firms survived:

- Realised profits, not maximum profits, are the marks of success and viability in any market. It does not matter through what process of reasoning or motivation that business success is achieved.

- Realised profit is the criterion by which the market process selects survivors.

- Positive profits accrue to those who are better than their competitors, even if the participants are ignorant, intelligent, skilful, etc. These lesser rivals will exhaust their retained earnings and fail to attract further investor support.

- As in a race, the prize goes to the relatively fastest ‘even if all the competitors loaf.’

- The firms which quickly imitate more successful firms increase their chances of survival. The firms that fail to adapt, or do so slowly, risk a greater likelihood of failure.

- The relatively fastest in this evolutionary process of learning, adaptation and imitation will, in fact, be the profit maximisers and market selection will lead to the survival only of these profit maximising firms.

The surviving firms may not know why they are successful, but they have survived and will keep surviving until overtaken by a better rival. All business needs to know is a practice is successful.

One method of organising production and supplying to the market will supplant another when it can supply at a lower price (Marshall 1920, Stigler 1958). Gary Becker (1962) argued that firms cannot survive for long in the market with inferior product and production methods regardless of what their motives are. They will not cover their costs.

The more efficient sized firms are the firm sizes that are currently expanding their market shares in the face of competition; the less efficient sized are those firms that are currently losing market share (Stigler 1958; Alchian 1950; Demsetz 1973, 1976). Business vitality and capacity for growth and innovation are only weakly related to cost conditions and often depends on many factors that are subtle and difficult to observe (Stigler 1958, 1987). The Employment Court pretends to know better than the outcome of the competitive struggle in the market for survival.

The Employment Court also believes employers have something akin to academic tenure. In 2010, the Court found that an employee’s redundancy was unjustified because the employer did not offer redeployment and there is no requirement that the right of the redeployment be written into the employment agreement (Wang v Hamilton Multicultural Services Trust). The particulars of this case were quite interesting:

- A new management role was created with significantly more responsibility for training, supervision and decision making than the redundant finance administrator role, with a 50% salary increase to recognise the increased responsibilities and duties.

- The vacancy was advertised externally but the existing finance administrator was encouraged to apply.

- His experience and qualifications meant that he could fulfil the new role, albeit with some up-skilling.

- He decided not to apply for it to avoid jeopardising a personal grievance claim that his redundancy was not genuine and therefore unjustified.

In the case at hand, the Employment Court held that the employer was obliged to look for alternatives to making the employee redundant. Given that he would be able to perform the new finance manager position with some up-skilling, the employer should have offered him the position rather than simply inviting him to apply for it.

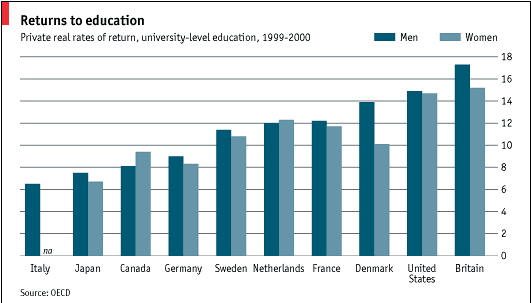

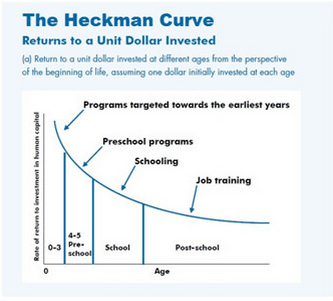

The notion that an employee through training can quickly increase their marginal productivity by 50% to fill a more senior role contradicts the modern labour economics of human capital. A 50% salary increase through a bit of training would imply extraordinary annual returns on other forms of on-the-job training and formal education as well as the training at hand in the Employment Court case.

I would very much like to be in the position where I can get a 50% salary increase after a bit of training. As I recall, I required about 5-10 years of on-the-job human capital acquisition before my starting salary as a graduate was 50% higher through promotion and transfers.

In summary, the Employment Court stands apart from the modern labour economics of human capital and job search and matching as well as the modern theory of entrepreneurial alertness, and the market as a discovery procedure and an error correction mechanism. The Employment Court has fallen for both the pretence to knowledge and the fatal conceit.

Mar 04, 2015 @ 12:01:54

Very Very interesting. In my Around the Traps!

Key must surely over-rule this.

LikeLike

Mar 04, 2015 @ 12:07:18

There is even a far worse one coming up on equal pay where the Court of Appeal upheld the right to compare equal pay between different workplaces rather than within the same workplace based on a 1971 Law people paid no attention to for 40 years

LikeLike

Mar 04, 2015 @ 15:02:08

again surely Key would intervene.

LikeLike

Mar 04, 2015 @ 18:19:10

Key Tried once already

LikeLike

Mar 05, 2015 @ 12:52:22

Hi Jim – fascinating graph above, “A chilling effect”. Where did it come from?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 05, 2015 @ 13:46:26

See http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/06/people.htm

LikeLike

Mar 05, 2015 @ 17:09:19

That’s great, thanks

LikeLike