Stossel – The Good New Days

23 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history Tags: pessimism bias, The Great Enrichment

Patrick Minford explains #Brexit

22 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economics, international economic law, international economics, International law, Public Choice Tags: Brexit, British economy, British politics, Common market, European Union

#Morganfoundation’s same #UBI of $11,000 per adult is now triple pledged

22 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, public economics

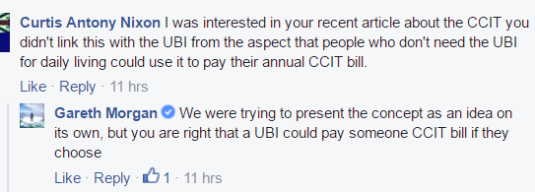

Before my two comments disappeared from Gareth Morgan’s Facebook page, I pointed out that his universal basic income of $11,000 per adult is as of last night at least triple pledged.

According to Gareth Morgan’s latest remark in the screenshot, people can use their universal basic income of $11,000 to pay their comprehensive capital tax bill. This new tax is proposed to fill the at least $10 billion gap in the funding of his universal basic income.

This is not possible because his universal basic income is already pledged to at least two other purposes that may use up a good part of the universal basic income of $11,000 per adult that he is proposing.

The first of these pledges is a by-product of adults under the age of 50 not being grandfathered in to the current level of generosity of New Zealand Superannuation – New Zealand’s universal old age pension.

Adults under the age of 50 under the Morgan Foundation’s universal basic income are expected to save part of their universal basic income. This saving is to make up for the $50 per week cut in New Zealand Superannuation when it is replaced by a universal basic income of $11,000 per adult. Gareth Morgan explains

Only people who are today under the age of 50 could be expected to retire under the UBI policy, the policy would not apply to existing superannuitants.

The key question is whether someone aged, say 40 today, would be better or worse off in retirement under the policy. And the answer is if they earn the average wage now, have an average house, they will tend to be neither better nor worse off.

For the 25 years prior to retirement they will receive the UBI on top of their wages. If they save a good portion of it they will have nest egg at retirement which they can use in retirement to supplement the UBI (which is more modest than today’s NZ Super).

In addition to this, the universal basic income makes those on a single parents benefit $150 a week worse off on the basic benefit that is not including lost accommodation supplements and additional child payments. The Morgan Foundation solution is to take part of the universal basic income of the other parent and give it to their children. Gareth Morgan explains again

It is totally feasible that the UBI of both parents could be required to be directed to support the children in the event of separation.

So in addition to the poor and ordinary families saving their universal basic income for as little as 15 years to making up for the $50 per week cut in support for old age pensioners, and the $150 plus cut in income support to single parents on a welfare benefit, the universal basic income also will be used to pay the comprehensive capital tax on the family home.

Somewhere buried in the universal basic income is it is the idea that it replaces existing welfare benefits. However, as most of the universal basic income has been pledged to other purposes such as saving for retirement, supporting children and paying the great big new tax in the family home, it will be very unwise to actually become unemployed, get sick, become a single parent or being invalid on the already meagre universal basic income as Geoff Simmons explains

With an unconditional basic income, most beneficiaries would be no better off than they are now (in fact sole parents would almost certainly receive a lower benefit).

There is a high risk that nothing will be left over from the Morgan foundation’s universal basic income to help you out when you fall in bad times because that universal basic income is already spoken for by your children, your retirement, and a capital tax bill.

Helping people out in times of misfortunes is the purpose of social insurance. The Morgan Foundation’s universal basic income fails this basic test set by Gareth Morgan

…let’s agree on what is a minimum income every adult should have in order to live a dignified life and then see what flows from that. We begin by specifying the income level below which we are not prepared to see anyone having to live.

At very best, and only very best, the Morgan Foundation’s universal basic income leaves some of those for whom social insurance was designed perhaps no worse. There are plenty of commonplace scenarios where individuals and families down on their luck are made much worse by a universal basic income replacing existing welfare benefits and plunged far deeper in poverty and hardship.

Mises on the Fatal Conceit

20 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, Ludwig von Mises, Public Choice

Adam Smith and the Follies of Central Planning

20 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in Adam Smith, applied price theory, applied welfare economics, Austrian economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, development economics, history of economic thought, Public Choice Tags: central planning, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

@ALeighMP, Lindsay Mitchell v. Susan St. John on family tax credit incidence

19 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand

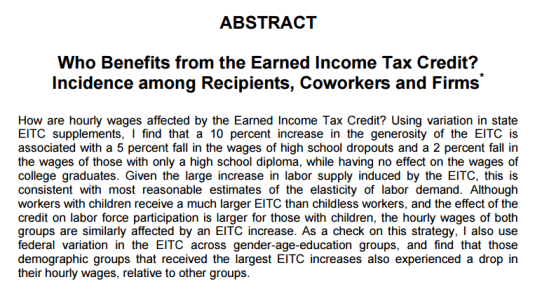

There is some feuding in the letters to editor page of the Sunday Star Times today between Lindsay Mitchell and Susan St John about whether employers pocket some of the Working for Families tax credit by reducing the wages they offer.

I have contracted-out my reply on the economic incidence of in-work tax credits to a former ANU economics professor who is now an Australian Labour Party federal MP.

There is general agreement such as summarised by the Economist that a significant part of family tax credits goes into the pockets of employers:

An analysis of the EITC published in 2010 by Andrew Leigh of the Australian National University found that most of the benefit of the credit went to workers. Not all of it did though: a 10% increase in the credit was associated with a 5% dip in wages of high-school dropouts. By the same token, a study conducted the following year by Mr Rothstein found that for each dollar spent on tax credits, existing workers’ income rose by $0.73 (although $0.09 of this was because they chose to work more). Employers gained $0.36, as they spent less on wages.

Economists at Britain’s National Institute of Economic and Social Research are conducting a similar study of the British system of tax credits. Childless workers become eligible for the credits at the age of 25. By comparing wages either side of this threshold, they have been able to estimate how much the credits are depressing wages. Their preliminary (and unpublished) results suggest that, of the 76p an hour the government forks out in tax credits for someone on the minimum wage, 72-79% goes to workers.

In work tax credits increases labour supply, which depresses wages except where wages are pressing up against a binding minimum wage. Steve Landsberg has pointed out a paradoxe of a binding minimum wage when there is an earned income tax credit:

If you increase the EITC in a market with an effective minimum wage, you’ll get a whole lot more workers competing for the same limited number of jobs, and this competition must continue until all of the benefits have either been dissipated or transferred to employers, who are now able to demand harder work and offer fewer perquisites.

@CloserTogether shows everyone in #NewZealand is much better off

19 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, politics - New Zealand, public economics

The chart below by poverty and inequality activists shows that Europeans, Maori and Pacifika are all much better off since 1988.

The increase in percentage terms for Maori and Pasifika household incomes is much larger than for Europeans as Bryan Perry (2015, p. 67) explains when commenting on table D6 sourced by Closer Together Whakatata Mai:

From a longer-term perspective, all groups showed a strong rise from the low point in the mid-1990s through to 2010. In real terms, overall median household income rose 47% from 1994 to 2010; for Maori, the rise was even stronger at 68%, and for Pacific, 77%. These findings for longer- term trends are robust, even though some year on year changes may be less certain. For 2004 to 2010, the respective growth figures were 21%, 31% and 14%.

The reforms of the 1980s known as Rogernomics stopped the long-term stagnation in real wages that started in about 1974 as the Facebook linked chart below shows.

The reforms of the early 1990s under a National Party government including a massive fiscal consolidation and the passing of the Employment Contracts Act was followed by the resumption of sustained growth in real wages with little interruption since. The good old days was long-term stagnation in wages. These economic reforms in the 1980s and 1990s also lead to a substantial decline in inequality.

New work by Chris Ball and John Creedy shows substantial *declines* in NZ inequality.

initiativeblog.com/2015/06/24/ine… http://t.co/f94fw4Bhae—

Eric Crampton (@EricCrampton) June 24, 2015

The wage stagnation in New Zealand in the 1970s and early 80s coincided with a decline in the incomes of the top 10%. When their income share started growing again for a short time in the 1980s, so did the wages of everybody after 20 years of stagnation.

The top 10% in New Zealand managed to restore their income share of the early 1970s and indeed the 1960s. That it is hardly the rich getting richer.

To paint pre-1984 New Zealand, pre-neoliberal New Zealand as an egalitarian paradise, as one of the most equal countries in the world, the Closer Together tweet and Max Rashbrooke both had to ignore 60% of the population and the inequalities they suffered.

“New Zealand up until the 1980s was fairly egalitarian, apart from Maori and women, our increasing income gap started in the late 1980s and early 1990s,” says Rashbrooke. “These young club members are the first generation to grow up in a New Zealand really starkly divided by income.”

Racism and patriarchy can sit comfortably with a fairly egalitarian society if you are to believe the Twitter Left. The biggest beneficiaries of the return of wages growth were Maori and New Zealand women. The gender wage gap in New Zealand is the smallest in the OECD.

Perry (2014) reviews the poverty and inequality data in New Zealand every year for the Ministry of Social Development. He concluded that:

Overall, there is no evidence of any sustained rise or fall in inequality in the last two decades. The level of household disposable income inequality in New Zealand is a little above the OECD median. The share of total income received by the top 1% of individuals is at the low end of the OECD rankings.

Hayek Lecture 2016: Price Stability and Financial Stability without Central Banks

19 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, Austrian economics, comparative institutional analysis, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: free banking

Expressive voting, more gun control or fewer gun free zones

18 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economics of crime, economics of regulation, law and economics, politics - USA Tags: expressive voting, game theory, gun control, offsetting the, unintended consequences

https://twitter.com/Thomas_Conerty/status/649800146528563200

If you want fewer mass shootings, reduce the supply of gun free zones where even the craziest gunmen have been able to find despite being tormented by the voices as John Lott explains

Time after time, we see that these killers tell us they pick soft targets. With just two exceptions, from at least 1950, the mass public shootings have occurred in these gun-free zones. From last summer’s mass public killers in Santa Barbara and Canada, to the Aurora movie theatre shooter, these killers made it abundantly clear in their diaries or on Facebook how they avoided targets where people with guns could stop them.

And even when concealed handgun permit holders don’t deter the killers, the permit holders stop them. Just a couple of weeks ago, a mass public shooting at a liquor store in Conyers, Ga., was stopped by a concealed handgun permit holder.

The USA is in an arms race between criminals and law-abiding citizens. Both have lots of guns so the only people who gain from disarmament to those who obey the law to have fewer guns. They are in a high gun equilibrium where it very difficult to get out of this arms race.

Demands for more gun control and bans on specific weapons postpone the hard work of how to reduce mass shootings in a society with easy gun access. It is expressive politics at its worse.

What does U.S. gun ownership really look like? Load up with #PollPosition’s @Johnnydontlike: bit.ly/1y2EMjX http://t.co/fn5EpM75U7—

(@PJTV) March 25, 2015

An Australian politician today in an unrelated context regarding universal health insurance in Australia called Medicare made this point about politics is hard work, not political theatre

It’s so much easier today to be a cynical poseur than a committed democrat, it’s easier to retreat to observer status than convince your friends of the merits of incremental change.

It required hard slog to ensure those institutions could survive the heat of adversarial politics. Then it took election campaign after election campaign, tough political negotiation, administrative effort, and the making and breaking of careers and governments to finally make Medicare stick,” she said.

The creation of Medicare took more than a hollow-principled stand, it took more than just wishful thinking, it took more than slogans, it took more than protests. It took real, tough politics. It took idealists who were prepared to fight to win government.

Expressive politics is about what voters boo and cheer, not whether policies actually work if adopted. Voters want to feel good about what they voted for and find a sense of identity in who they oppose and what they support. After a mass shooting, voters feel they must do something, cheer for something better and cheering for more gun control is an easy way to feel better.

Gun control is not going to happen in the USA because of the poor incentives for law-abiding individuals to retreat from high levels of legal private gun ownership when criminals will keep their guns. Harry Clarke pointed out that:

The political popularity of guns is strengthened by Prisoner’s Dilemma disincentives for individuals to retreat from high levels of gun ownership.

Accepting a gun buyback would be unattractive to citizens who would recognize high levels of overall gun ownership in the community and, hence, their own personal increased vulnerability if those with criminal intent acted rationally and kept their weapons.

If you want fewer mass shootings, fewer gun free zones is the way to go. That might have other unintended consequences but more mass shootings is not likely to be one of them. Ready access to guns in moments of despair increases suicide rates. Suicides in the Israeli Defence Force fell 40% when young soldiers were not allowed to take their guns home at the week-end. Suicides do not increase during the week so the lack of weekend access to guns got them through dangerous moments of despair where ready access to a firearm would have led to a suicide.

The last thing spree killers want is to be quickly shot down like the dogs they are such as at an American church in 2007. The last wannabe jihadist to try it on in Texas died in a hail of gunfire.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s National Crime Victimization Survey showed the risk of serious injury from a criminal attack is 2.5 times greater for women offering no resistance than for women resisting with a gun. 97% of murders are by men. Any arguments about gun control should be about gun control for men.

The sharemarket perception of gun control is every time there are calls for more gun controls, the share prices of gun manufacturers surge of the back of an anticipated spike in sale. Buying two gun shares on the first trading day after 12 recent mass shootings and selling them 90 days later produces a return of 365% over a nine-year period compared to 66 percent for the S&P 500 Index. A buy-and-hold bet on Smith & Wesson stock starting in January 2007returns 137%.

What gun-control headlines mean for gun-industry bottom lines: reut.rs/20LPJGf via @specialreports https://t.co/R3QiG4MuSM—

Reuters Top News (@Reuters) February 05, 2016

The key to the success of Australian and New Zealand gun laws was low levels of gun crime and minimal use of guns for self-defence. There was no arms race as compared to the USA where criminals and civilians are both armed. It is easy to control an arms race that has not started. The New Zealand, Australian and even the British police rarely have to discharge their weapons.

Martin Luther King was a gun owner for obvious reasons. Tom Palmer was the lead litigant in the recent Supreme Court case on gun control in the USA. He saved himself and a fellow gay man from a severe beating in 1987 by gang of 20 men by pulling a gun on them. Pink pistols has been in the thick of anti-gun control litigation in the USA.

Deirdre McCloskey on the Nirvana fallacy in public policy

18 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economic history, Public Choice

Source: Quotation of the Day… – Cafe Hayek.

James Heckman on the Economics of Human Development

14 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, discrimination, economics, economics of education, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality Tags: James Heckman

@Noahpinion says 20% losing their jobs is a small price to pay in #fightfor15

14 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, labour economics, minimum wage, Robert E. Lucas

https://twitter.com/EconBizFin/status/626687442834300928

Noah Smith is a type of friend that should make poor Americans prefer their republican enemies. At least they are not fanatics. Fanatics never give up. Evil people have other things to do with their dastardly days.

Source: A Higher Minimum Wage Won’t Lead to Armageddon – Bloomberg View.

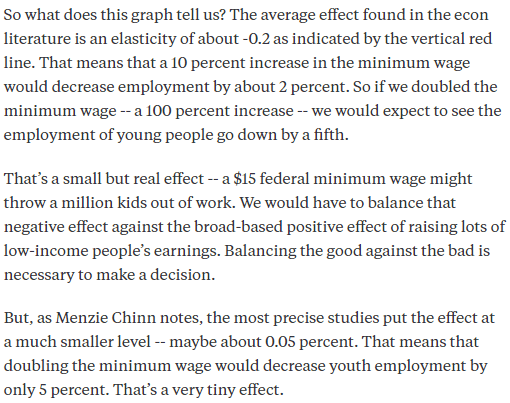

Describing 1/5th of young people losing their jobs after a doubling of the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour as a small but real effect is a type of callousness that not even Donald Trump could stoop. What is Even Noah Smith admits that large minimum wage increases experiment with the fortunes of young people

We don’t really know what happens when you raise the minimum wage to $15 — but soon, we will know. We will be able to see whether employment rates fall in L.A., Seattle, and San Francisco.

We will be able to see whether people who can’t get work migrate from these cities to cities with lower minimum wages. We will be able to see if employment growth suddenly slows after the enactment of the policy. In other words, federalism will do its job, by allowing cities to act as policy laboratories for the rest of the country.

These one million young people who may well lose their jobs under a $15 minimum wage are real living people starting out their work in lives in a country with a rather inadequate unemployment benefits especially for the long-term unemployed.

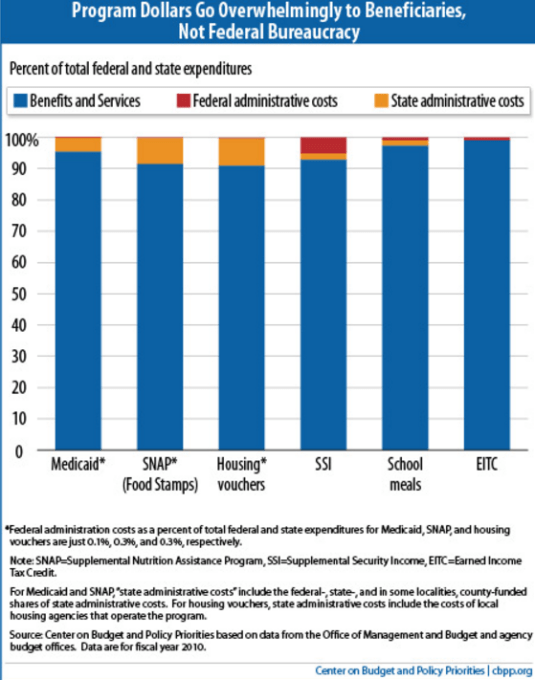

Noah Smith wants to throw them onto the scrapheap through a large increase in the minimum wage because he is too cheap to support a large increase in the earned income tax credit.

If doubling the minimum wage to throw 20% of the workforce out of a job passes the brutal utilitarian calculus of bleeding-heart progressives, why not double everybody’s wages? Show the strength of your conviction about these Kruger–Card minimum wage results which repeal the laws of supply and demand.

https://twitter.com/AlvaroLaParra/status/738776906988822528

The leading reason for empirical research and economic history is to warns us not to repeat the mistakes of the past and not try experiments that are obvious folly. People and the economy should not be used as lab rats as Lucas explains in his short speech “What Economists Do”

I want to understand the connection between the money supply and economic depressions.

One way to demonstrate that I understand this connection–I think the only really convincing way–would be for me to engineer a depression in the United States by manipulating the U.S. money supply.

I think I know how to do this, though I’m not absolutely sure, but a real virtue of the democratic system is that we do not look kindly on people who want to use our lives as a laboratory. So I will try to make my depression somewhere else.

Bill Maher: Sanders Supporters Are “Used To Getting Shit For Free”; That’s Not Socialism, It’s “Santa-ism”

13 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, defence economics, economic history, economics of education, economics of media and culture, economics of regulation, environmental economics, industrial organisation, politics - USA, survivor principle Tags: 2016 presidential election, Twitter left

Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government Is Smarter

11 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economics, economics of information, income redistribution, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking Tags: rational ignorance, rational irrationality, voter demographics

Recent Comments