@Income_Equality this mostly criticises @annetterongotai @AndrewLittleMP

11 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, health economics, politics - New Zealand

Solution aversion and the anti-science Left

11 Mar 2016 1 Comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economics of regulation, energy economics, environmental economics, global warming, health economics, law and economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, property rights, Public Choice Tags: antiscience left, climate alarmism, geo-engineering, GMOs, growth of knowledge, gun control, motivated reasoning, nuclear power, political persuasion, solar power, solution aversion, wind power

Climate science is the latest manifestation of solution aversion: denying a problem because it has a costly solution. The Right does this on climate science, the Left does it on gun control, GMOs, and plenty more. Cass Sunstein explains:

It is often said that people who don’t want to solve the problem of climate change reject the underlying science, and hence don’t think there’s any problem to solve.

But consider a different possibility: Because they reject the proposed solution, they dismiss the science. If this is right, our whole picture of the politics of climate change is off.

Some psychologists wasted grant money on lab experiments to show that people that think the solution to a problem is costly tend to rubbish every aspect of the argument. Any politician will tell you you do not concede anything. Sunstein again:

Campbell and Kay asked the participants whether they agreed with the IPCC. And in both, about 80 percent of Democrats did agree; the policy solutions made no difference.

Republicans, in contrast, were far more likely to agree with the IPCC when the proposed solution didn’t involve regulatory restrictions…

Here, then, is powerful evidence that many people (of course not all) who purport to be skeptical about climate science are motivated by their hostility to costly regulation.

The Left is equally prone to motivated readings. For example, it was found that those on the left are much more concerned about home invasions when gun control can reduce them rather than increase them.

The Left picks and chooses which scientific consensus as it accepts. The overwhelming consensus among researchers is biotech crops are safe for humans and the environment. This is a conclusion that is rejected by the very environmentalist organisations that loudly insist on the policy relevance of the scientific consensus on global warming.

Previously the precautionary principle was used to introduce doubt when there was no doubt. But when climate science turned in their favour, environmentalists wanted public policy to be based on the latest science.

The Right is welcoming of the science of nuclear energy or geo-engineering. The Left rejects it point-blank. Their refusal to consider nuclear energy as a solution to global warming is a classic example of solution aversion. Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.

Monopolies and patents can breed deadweight loss and market inefficiencies

11 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, law and economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, property rights Tags: intellectual monopolies, patents and copyright

Everybody is at least 40% richer than in 1979

10 Mar 2016 1 Comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, economics Tags: The Great Fact

Negative Externalities and the Coase Theorem

06 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, history of economic thought, law and economics, property rights Tags: Coase theorem

This @amprog lead in picture and its 1st figure about minimal improvement in living standards in 30 years just does not gel somehow

05 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, economics of media and culture, industrial organisation, politics - USA Tags: good old days, Leftover Left, pessimism bias, rational irrationality, smart phones, The Great Enrichment

Source: When I Was Your Age | Center for American Progress.

The claim by the Centre for American progress is that despite being more educated and working in a more productive economy, 30-year-olds today barely make more than 30-year-old Baby Boomers did in 1984.

Source: When I Was Your Age | Center for American Progress.

Nearly everything from RadioShack ad in 1991 is replaced by a smartphone. https://t.co/xGh6ZzW1Nx—

Vala Afshar (@ValaAfshar) December 19, 2015

The apps in your smartphone cost $900,000 thirty years ago —@datarade https://t.co/pjw7q4QGDp—

Vala Afshar (@ValaAfshar) October 29, 2015

On playing God at Pharmac

01 Mar 2016 1 Comment

in applied welfare economics, health economics

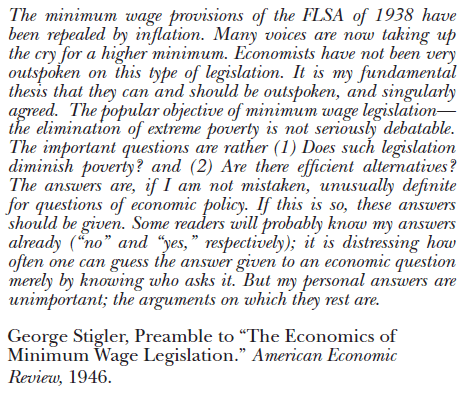

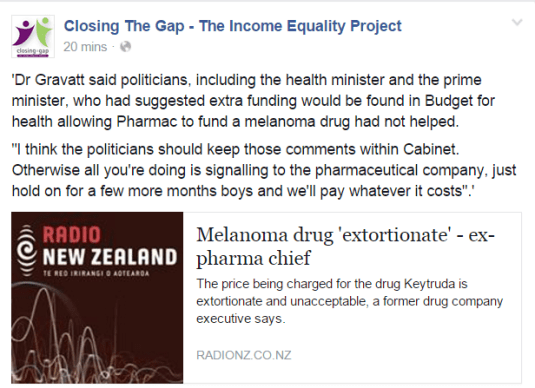

I unsuccessfully tried to get a list of all the drugs that had a stronger case for funding than Keytruda. The Labor Party wants that to be given priority – jump the queue.

I asked for the cost of each drug that is above Keytruda and the cut-off point for PHARMAC funding of drugs in the last four years. The first part about the cost of drugs was refused on commercial in confidence grounds.

My inquiries about a list of drugs queued up for funding that will get funding as soon as money becomes available lead to an intriguing answer by Pharmac in their response to my Official Information Act request:

For the second part of your request, PHARMAC makes its funding decisions based on its legislative objective, ‘to secure…the best health outcomes that can reasonably be achieved from pharmaceutical treatment and from within the amount of funding. Therefore, there is no cut-off value, threshold or other criteria relating to a fixed point.

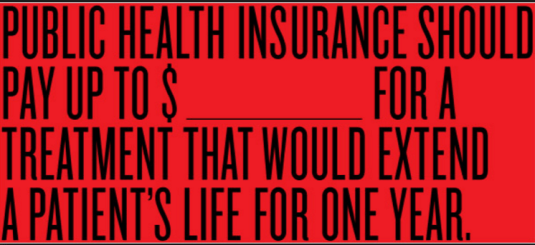

This lack of a queue or cut-off point lead me to ponder how funding is allocated between life-saving and other medications, between painkillers and routine medications that are not about relieving suffering.

Source: Pharmac Making Funding Decisions factsheet.

So at the bottom of it all a certain amount of funding is available for different types of drugs ranging for miracle drugs to routine medications. Cost benefit analysis cannot really help you with that because all would tell you is to spend all your money on the life-saving drugs but we live our lives out in pain as few other drugs are available to us. At bottom, someone must play God and say that a certain amount of the budget is available to save lives.

That philosopher God King must first decide how big the health budget is and then how big the Pharmac budget is. Within the Pharmac budget, certain rather arbitrary decisions must be made as to how much is spent on life-saving drugs. Peter Singer had one of his good days when he said:

Governments implicitly place a dollar value on a human life when they decide how much is to be spent on health care programs and how much on other public goods that are not directed toward saving lives.

The task of health care bureaucrats is then to get the best value for the resources they have been allocated. It is the familiar comparative exercise of getting the most bang for your buck. Sometimes that can be relatively easy to decide. If two drugs offer the same benefits and have similar risks of side effects, but one is much more expensive than the other, only the cheaper one should be provided by the public health care program. That the benefits and the risks of side effects are similar is a scientific matter for experts to decide after calling for submissions and examining them. That is the bread-and-butter work of units like NICE.

But the benefits may vary in ways that defy straightforward comparison. We need a common unit for measuring the goods achieved by health care. Since we are talking about comparing different goods, the choice of unit is not merely a scientific or economic question but an ethical one.

Singer then goes on to talk about quality adjusted life years as the measure economists use. Still very subjective because people have enough trouble working out the value of a life saved – the value of the statistical life.

Quantifying the quality of life is even bigger leap for bureaucrats. That is not to belittle their effort. At least it is an attempt to be upfront about making difficult choices in medical rationing.

Health care does more than save lives: it also reduces pain and suffering. Tragic choices must be made as only so much spending is on saving lives; the rest will be spent on relieving pain and suffering.

We should be upfront about that so we are not captured by the identifiable victim effect. Giving money to an identifiable victim is money taken from many other health budget purposes that also save lives and relieve suffering.

Will there be poverty on the Starship Enterprise?

26 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, poverty and inequality

A Facebook photo by Mary Ruwart reminded me of the question I posed in previous blog posts about whether there will be poverty on the Star Trek enterprise. Those security officers in the red tunics get a really bad deal, especially if they beam down to the planet with Captain Kirk.

Data chauvinism versus the 1st law of public policy development

25 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economics of bureaucracy, Public Choice

I learnt at the Australian Productivity Commission that the first law of public policy development is plagiarise, plagiarise, plagiarise. Why be original? Copy the successes of others, improve upon them, but do not repeat their failures, just learn from them.

I developed this policy insight from my experience at the Productivity Commission with a smart-arse Commissioner – that was the chairman’s private description of him in a conversation with me, not mine.

This Commissioner with whom I had countless arguments would respond to the many US studies I had marshalled by always asking for Australian evidence – what is the Australian evidence?

He knew that there was no Australian data or studies so he could slow the whole policy process down through this appeal to data chauvinism. The Americans are swimming in data and that is before you get to their cross-sectional data with 50 states.

Ever since then, I regarded data chauvinism – the request for Australian evidence and studies or New Zealand evidence and studies – as a stalling tactic designed either to defend the status quo.

Ever since then, I regarded data chauvinism – the request for Australian evidence and studies or New Zealand evidence and studies – as a stalling tactic designed either to defend the status quo.

By and large, all the local evidence shows when it augments the US studies is how a local regulation or tax screws things up further. Local evidence rarely served the interests of my opponents who were fighting against deregulation or privatisation.

It is a good public policy – you are much more likely to implement a proposal or act on a particular empirical study – if there are half a dozen to a dozen overseas studies preferably in several different countries showing much the same thing. Beware the man of one study. Milton Friedman (1957) rightly preferred to emphasize the congruence of evidence from a number of different sources and with due attention to the quality of the data:

I have preferred to place major emphasis on the consistency of results from different studies and to cover lightly a wide range of evidence rather than to examine intensively a few limited studies.

The role of empirical evidence is to resolve disagreements – to bring people closer together. One study in one country rarely does that. Many studies in many countries about the same topic of controversy is far more persuasive.

Recent Comments