Maxim Pinkovskiy and Xavier Sala-i-Martin last year suggested that national accounting estimates of poverty should be adjusted for the evolution of satellite-recorded night-time lights. I agree from personal experience.

In India between 1994 and 2010, its survey income grew by 29% but its GDP per capita more than doubled during this time. We see that lights in India increase dramatically both in their intensity over the major cities as well as in their extent over previously dark areas of the country. This suggests that the GDP estimate is a more accurate assessment of economic development of India and the faster reduction of poverty than income surveys suggest.

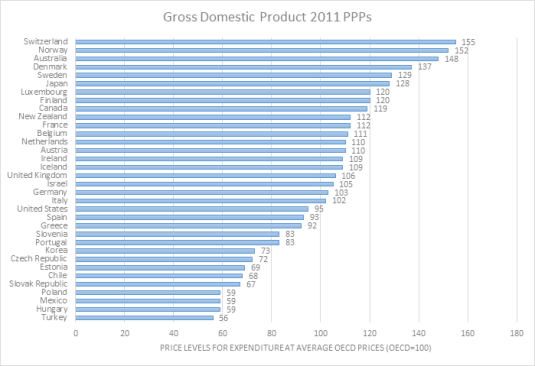

Source: The Conference Board. 2015. The Conference Board Total Economy Database™, May 2015, http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/

National accounting data on real GDP, PPP would suggest that Indonesia is a much wealthier country than the Philippines. The Philippines from about the late 1998, has had rapid economic growth, but so has Indonesia. I first visited the Philippines in 1997. I have never visited Indonesia.

When I first visited my parents-in-law in the Philippines in 1998, that part of Leyte had no sealed roads and no phones.

The next time I visited, the road was being sealed and mobile reception was better if you had an aerial on the roof.

After a five year gap in visiting, not only was mobile reception good, there was cable TV if you wanted it. When I visited in 2012, there was wireless internet if you had outside aerial.

Christmas before last, we hot spotted off my sister-in-law’s mobile. Neighbours have Skype if we want to say hello. I don’t know how that rapid change in economic fortunes is captured accurately in national accounting figures.

Recent Comments