Hall and Scobie (2005) attributed 70 percent of the labour productivity gap with Australia to New Zealand workers using less capital per worker than their Australian counterparts, rather than their using w3capital less efficiently. Figure 1 shows that the capital labour ratio is lower in New Zealand than in Australia and has been lower than Australia for several decades and is getting worse.

Figure 1: Capital intensity in New Zealand relative to Australia: 1978-2002

Source: Hall and Scobie 2005.

In 1978, New Zealand and Australian workers had about the same amount of capital per hour worked. By 2002, capital intensity in Australia was over 50 percent greater than in New Zealand. This lower rate of capital intensity is capital shallowness.

Capital should flow to countries with the highest risk adjusted rates of return. If workers in a country work with less capital than in other countries, the rate of return on providing them with more capital is higher than the global average return to capital. As Stigler (1963) said:

There is no more important proposition in economic theory than that, under competition, the rate of return on investment tends toward equality in all industries.

Entrepreneurs will seek to leave relatively unprofitable industries and enter relatively profitable industries, and with competition there will be neither public nor private barriers to these movements.

This mobility of capital is crucial to the efficiency and growth of the economy: in a world of unending change in types of products that consumers and businesses and governments desire, in methods of producing given products, and in the relative availabilities of various resources—in such a world the immobility of resources would lead to catastrophic inefficiency

Hall and Scobie (2005) acknowledged that lower capital intensities could be entirely a by-product of lower MFP. New Zealand had the third worst MFP growth performance since 1985, one quarter the OECD average (OECD 2009).

Rather than money being left on the table by persistent, known but unexploited entrepreneurial opportunities for pure profit by investing more in under-capitalised New Zealand and providing additional capital and equipment and more advanced technologies for New Zealanders to work with, investors have done the best they could the relative poor investment opportunities here.

Figure 2: Differences in capital intensity: the case of different production functions

Source: Hall and Scobie 2005.

A divergence in labour productivity levels between Australia and New Zealand emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. Kehoe and Ruhl (2003) attributed 96 percent of the fall in labour productivity in New Zealand between 1974 and 1992 to a fall in MFP. Changes in capital intensities played a minor role.

Aghion and Howitt (2007) found that three-quarters of the growth in output per worker in Australia and New Zealand between 1960 and 2000 was due to growth in MFP. New Zealand’s annual MFP growth of 0.45 percent between 1960 and 2000 was simply much lower than Australia’s 1.26 percent per year. Capital deepening was equally lower in New Zealand with 0.16 percent comparing to 0.41 percent in Australia.

Less would be invested in a country if the returns are lower because the capital is poorly employed. There might be a lack of complementary skills and education and, more often, policy distortions that lower MFP (Alfaro et al 2007; Caselli and Feyrer 2007; Lucas 1990).Investment in ICT capital is greatest in the USA because it is the global industrial leader and has very flexible markets. Investment in ICT in the EU is proportionately less because less flexible markets make ICT investments in the EU members less fruitful to investors.

To explore the relative role of lower MFP and the cost of capital in capital shallowness, Hall and Scobie (2005) used national accounts data to estimate the cost of capital and found that New Zealand faced a higher cost of capital than Australia, the USA and the OECD average since the early 1990s. Research that is more recent disputes these concerns about a higher cost of capital in New Zealand.

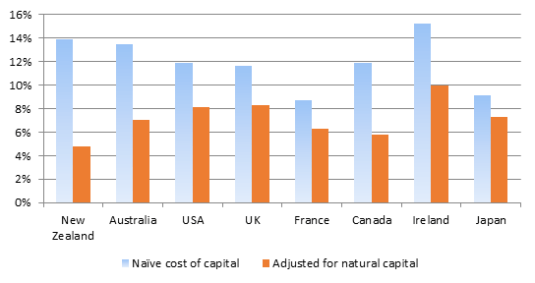

In Caselli and Feyrer’s (2007) revised cost of capital estimates, the cost of capital is significantly lower in New Zealand than in Australia and elsewhere in the OECD area such as the USA, Japan and UK – see Figure 3. Caselli and Feyrer (2007) correct for an overestimation of the cost of capital that is prevalent for countries such as New Zealand where the value of land and natural resources are high.

Figure 3: Caselli and Feyrer’s Estimates of the Cost of Capital, 1996

Source: Caselli and Feyrer (2007); Hsieh and Klenow (2011).

Notes: The measure of capital income used by Hall and Scobie (2005) to calculate the cost of capital includes payments to reproducible physical capital (equipment, machinery, ICT, buildings and other structures) as well as payments to natural capital (land and natural resources). Dividing the income that flows to all types of capital including land and natural resources by just the value of reproducible physical capital overestimates the cost of capital. Caselli and Feyrer (2007) used World Bank (2006) estimates of natural capital stocks in 1996 to estimate of income flows to reproducible physical capital. Their estimates excluded income flows to land and natural resources to estimate the cost of reproducible capital.

Caselli and Feyrer (2007) revised estimate in Figure 3 is for the cost of capital for investing in equipment, machinery, ICT, buildings and structures. When land and resources are included, shown in light blue as the naive cost of capital, the estimated cost of capital is one-half of percentage point higher in New Zealand than in Australia and two percent higher in New Zealand than the USA and UK in Figure 3. When land and natural resources are excluded, shown in red as the adjusted for natural capital estimate, the cost of capital is much lower in New Zealand than in Australia, the USA, Japan and UK – see Figure 3.

What Caselli and Feyrer (2007) show is the estimation of the cost of capital to New Zealand is fraught with statistical difficulties. A broader data set yields radically different results. That is the broader lesson.

At a minimum, safest thing to say, is there are no reliable estimates of the cost of capital in New Zealand. Depending on how you measure it, the cost of capital in New Zealand is either much higher or much lower than in the leading industrial countries such as the USA and UK. Such a broad range of estimates is no basis for public policy interventions.

When having to choose between arguing for a persistent, known but unexploited entrepreneurial opportunities for risk-free profit left on the table in New Zealand by foreign investors for decades, and measurement error in the case of one of the nastiest measurement jobs – measuring capital and natural resources – measurement error is more likely.

Capital is the most internationally mobile of factors of production. Entrepreneurs have every incentive to move it to new destinations with higher risk-adjusted rates of returns. Returns will not be exactly equal, but there will be a tendency for equalisation subject to these reservations listed by George Stigler in 1963:

- Some dispersion in rates of return exist because of imperfect knowledge of returns on alternative investments.

- Dispersion of returns would arise because of unexpected developments and events which call for movements of resources requiring considerable time to be completed.

- Dispersion in rates of return would arise because of differences among industries in monetary and nonmonetary supplements to the average rate of return.

- In any empirical study, there is also a fourth source of dispersion: the difference between the income concepts used in compiling the data and the income concepts relevant to the allocation of resources.

The last of these reservations listed by George Stigler in 1963 about the statistical concepts used in compiling what data can be collected and the concepts relevant to the entrepreneurial decisions about the allocation of resources appear to be crucial to the debate about capital shallowness in New Zealand. They also echo Hayek’s great reservation in his 1974 lecture The Pretence to Knowledge about focusing on what can be measured rather than what is important in both economic analysis and public policy making:

We know: of course, with regard to the market and similar social structures, a great many facts which we cannot measure and on which indeed we have only some very imprecise and general information. And because the effects of these facts in any particular instance cannot be confirmed by quantitative evidence, they are simply disregarded by those sworn to admit only what they regard as scientific evidence: they thereupon happily proceed on the fiction that the factors which they can measure are the only ones that are relevant.

Hall and Scobie (2005) were careful scholars who noted that possibility that the apparent capital shallowness in New Zealand is merely the result of measurement error because of the problems of measuring land and natural. Caselli and Feyrer (2007) justify their caution and vindicated the view that the marginal product of capital is pretty much the same all round the world. As Caselli and Feyrer (2007) explain:

There is no prima facie support for the view that international credit frictions play a major role in preventing capital flows from rich to poor countries.

Lower capital ratios in these countries are instead attributable to lower endowments of complementary factors and lower efficiency, as well as to lower prices of output goods relative to capital. We also show that properly accounting for the share of income accruing to reproducible capital is critical to reach these conclusions.

There is various debates in policy circles in New Zealand about this lack of capital per worker and a higher cost of capital in New Zealand.

But that debate and any policy measures that were introduced as a result may be misplaced and all due to measurement error, or more correctly the grave difficulties of measuring both the capital stock and the cost of capital, both generally and in New Zealand course of its large bounty of natural resources. The data was always in doubt, so any policy interventions should be very cautious and incremental.

It would have been surprising to find that lower productivity in New Zealand was due to a lack of access to capital. There is growing evidence that capital intensities are not a major contributor to cross-national per capita income gaps.

There is a broad empirical consensus that capital intensity explains about 20 per cent of cross-country income differences; differences in human capital account for 10 to 30 per cent of cross-national differences with MFP accounting for the remaining 50 to 70 percent (Hsieh and Klenow 2011).

The New Zealand capital shallowness hypothesis is too marred in measurement shortcomings to rebut this broad empirical consensus about MFP differences between all other countries. For example, when reviewing the trans-Atlantic productivity and income gap, Edward Prescott said:

The capital factor is not an important factor in accounting for differences in incomes across the OECD countries… [It] contributes at most 8 percent to the differences in income between any of these countries.”

At the broader level, this blind alley about capital shallowness in New Zealand illustrates the pretence to knowledge. The politicians and bureaucrats pretended to know the cost of capital and the size of the capital stock in New Zealand and then work out what to do in response while doing more good than harm. This was despite serious reservations about the quality of data at hand.

This blind alley about the cost of capital and capital shallowness in New Zealand illustrates Josh Lerner’s point about distractions such as these and their many equivalents overseas reinforce the importance of the neglected art of setting the table– of fostering a favourable business environment. The neglected art of setting the table includes:

- investing in a favourable tax regime (low taxes on capital gains relative to income tax are particularly important as studies show people respond to incentives); and

- making the labour market more flexible (again the opposite of what has happened in continental Europe ),

- reducing informal and formal sanctions on involvement in failed ventures;

- easing barriers to technology transfer, and

- providing entrepreneurship education for students and professionals alike.

Recent Comments