Price Floors: The Minimum Wage

17 Jun 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: price controls

PRECARIOUS WORK AS THE FLIP SIDE OF EFFICIENCY WAGES

02 Jun 2017 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, Marxist economics, minimum wage, poverty and inequality, unemployment Tags: living wage

Efficiency wages were put forward as a cause of what is now called precarious work. The efficiency wage hypothesis breathed considerable new life into the old theory of dual labour markets (Katz 1986; Dickens and Lang 1985).

The notion of a segmented labour market, of a primary and a secondary labour market, each with distinctly different wage setting mechanisms, was very much a fringe idea prior to the 1980s:

Efficiency wage theory provides a rare common meeting ground for mainstream and radical economists, because the far left in U.S. economics has taken the lead in developing theories of dual labor markets and for setting-out policy proposals for higher minimum wages based on the assumed validity of the efficiency wage approach (Gordon 1990, p. 1157).

The workers privileged enough to hired by firms paying an efficiency wage would enjoy job security, low job quit rates, good working conditions, career advancement, training and higher pay (Akerlof 1982, 1984; Bulow and Summers 1986; Dickens and Lang 1993). The remaining equally productive workers who were unlucky enough to be priced out of these good jobs by the job rationing implicit in an efficiency wage must fend for themselves in a secondary labour market; in precarious work with high quit rates, harsh workplace discipline, few promotions, little training and poor pay (Akerlof 1982, 1984; Katz 1986; Dickens and Lang 1985). Efficiency wages do not motivate greater employee effort unless the prospect of precarious work in this secondary labour market looms large in the back of their minds as their main alternative source of employment for those lucky enough to be employed in the good jobs in the primary labour market (Katz 1986; Bulow and Summers 1986).

Those workers crowded into these bad jobs in the secondary labour market find it to be a slow and difficult process to break into these better paying good jobs in the primary labour market. There are queues for the good jobs because they are paying above-market wages; many of those crowded into the bad jobs are women and minorities (Bulow and Summers 1986; Dickens and Lang 1985, 1993).

Akerlof, in his Nobel Prize lecture on behavioural macroeconomics, contended that the good and bad jobs caused by paying efficiency wages is central to explaining involuntary mass unemployment:

The existence of good jobs and bad jobs makes the concept of involuntary unemployment meaningful: unemployed workers are willing to accept, but cannot obtain, jobs identical to those currently held by workers with identical ability. At the same time, involuntarily unemployed workers may eschew the lower-paying or lower-skilled jobs that are available. The definition of involuntary unemployment implicit in efficiency wage theory accords with the facts and agrees with commonly held perceptions. A meaningful concept of involuntary unemployment constitutes an important first step forward in rebuilding the foundations of Keynesian economics (Akerlof 2002, p. 415).

Living wage activists already doubt that the market can provide steady wages growth and stable employment. Efficiency wages are a leading New Keynesian macroeconomic explanation for that. The living wage movement cannot pick and choose from what the efficiency wage hypothesis says about how well the labour market functions for those who are and are not in efficiency wage jobs.

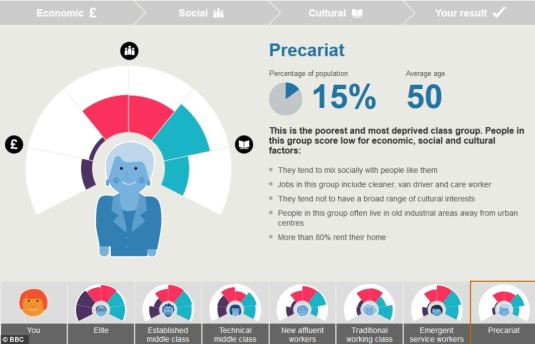

Living wage activists are unwittingly following a course of action that leads to more job rationing, more precarious work and more unemployment. Those priced out of council jobs by a living wage such as the 17 parking wardens are left to take their chances in the rest of the local labour market. These workers must take bad jobs while queueing for the good jobs in the primary labour market. Instead of being sources of opportunity in their communities, councils through a living wage policy risk becoming drivers of labour market segmentation and the fostering of a precariat.

Short Cut: Macron’s Scandi-Solution for France

16 May 2017 Leave a comment

in economics, fiscal policy, labour supply, macroeconomics, minimum wage, Public Choice, public economics, welfare reform

#livingwage movement just can’t handle the truth @LWEmployerNZ

27 Apr 2017 Leave a comment

in industrial organisation, labour economics, labour supply, minimum wage, personnel economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: conjecture and refutation, critical discussion, crybaby left, living wage, Twitter left

Looks like the living wage movement will not be taking up my challenge for a public debate anytime soon.

It is illegal to mention the 3% minimum wage increase surcharge in New York State

13 Mar 2017 Leave a comment

The Racist Origin of the Minimum Wage — Deirdre McCloskey

03 Mar 2017 Leave a comment

in economics, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - USA

What’s the Right Minimum Wage?

25 Feb 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

Deirdre McCloskey on the Unsavory History of the Minimum Wage – Cafe Hayek

14 Feb 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economic history, history of economic thought, labour economics, minimum wage

The compassion of unions towards the minimum waged

24 Jan 2017 1 Comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, poverty and inequality, unemployment, unions Tags: do gooders, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge

Source: page 451 and page 828 of the 3rd edition (1972) of University Economics by Armen Alchian and William Allen; the first part of the quotation is Question #30 at the end of Chapter 22. via Bonus Quotation of the Day… – Cafe Hayek

Thomas Sowell – Black Lives and Social Policy

08 Dec 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, economics of education, human capital, labour economics, minimum wage, occupational choice, poverty and inequality, unemployment Tags: economics of families, racial discrimination, Thomas Sowell

The old and new theories of monopsony have clashing predictions

06 Dec 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: job search and matching, monopsony

Robinson’s (1933) theory of monopsony, of employer market power, is about fewness in the number of employers allow them to pay below-market wages. This means a minimum wage will raise wages, employment and, importantly, output. Her’s is a joint hypothesis. Employers will hire more workers and will produce more which means the firm must cut its prices to sell this additional output.

The new theories of monopsony such as in Manning’s Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in the Labour Market have ambiguous predictions about output and employment because they arise out of how the surplus from job matching is split. They acknowledge the possibility that some firms will close because they cannot afford the higher minimum wage rate.

The old monopoly monopsony theories are vindicated if output rises and prices fall as they must to sell the additional output. The new monopsony theories are vindicated if some firms close but employment does not fall much.

Because the new monopsony theories arise from a specific hypothesis about the labour market that it more difficult for larger employers to recruit, Kuhn (2005) argued that the title “Search Models with Ex-Ante Posted Wages in Motion, while considerably more accurate than Monopsony on Motion, is less catchy”.

Recent Comments