Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

12 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, Austrian economics, business cycles, economic growth, F.A. Hayek, fiscal policy, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, unemployment, unions Tags: job search, mismatch unemployment, search unemployment, union power, union wage premium, waiting unemployment

04 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in business cycles, currency unions, Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: central banks, liquidity trap, monetary policy

02 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, business cycles, economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics, movies Tags: bank runs, financial crises

About the only time the Hollywood Left oozes with patriotism is when getting stuck into Wall Street. Hollywood must get its revenge for all those times investors did not back their film pitches, trimmed budgets and get the lion’s share of merchandising royalties and syndication profits. As Larry Ribstein explained:

American films have long presented a negative view of business…. it is not business that filmmakers dislike, but rather the control of firms by profit-maximizing capitalists… this dislike stems from filmmakers’ resentment of capitalists’ constraints on their artistic vision.

The Big Short is still a good film despite the left-wing populism, worth going to see. Its limitations in not discussing the monetary policy of The Fed or regulations that encouraged lending to high risk borrowers are justified poetic license and editing.

The film is already 120+ minutes long despite frequent resorts to breaking the fourth wall to explain technical terms, who was what and what they were doing, past and present. The Big Short is a film designed it make money at the box office, not a semester long documentary.

The Big Short is well acted, funny, insightful and still a good story despite the documentary element that was impossible to do without.

The Big Short highlights that its protagonists had skin in the game. They were investing in mortgages or shorting the same in the expectation of a crash. There were no windbags and armchair critics in The Big Short talking gloom and doom on the horizon without investing their own money to profit from their forecasts. That said, the protagonists betting on a sub-prime mortgages crash, bar two of them, were a little bit nutty.

I do not know any of the critics of the economics of the film’s explanation of the sub-prime crisis who suggested how they could fix these gaps in its economics without making the film much, much longer.

These critics fall into the exact same trap that the Big Short was not about. The Big Short was about investors to put their money where their mouth is. The critics of the film should put their script doctoring skills where their mouths are at least of The Big Short.

Source: What ‘The Big Short’ Gets Right, and Wrong, About the Housing Bubble – The New York Times.

Getting stuck into the role of the Fed and regulatory mandates on the banks regarding their level of sub-prime mortgages is for another film. Plenty of people warned of dark days ahead. An essay anyone can read with profit is Ross Levine’s “An Autopsy of the U.S. Financial System: Accident, Suicide, or Negligent Homicide?“

Other films, correctly documentaries, place the blame for the sub-prime crisis and the Great Recession directly on the Fed:

The financial mess we’re still climbing out of can be laid directly at the feet of the Fed, whose misguided advocacy, under Greenspan, of a borrow-and-spend economy rather than a focus on savings and investment has created a situation where, as the title implies, money is disconnected from any underlying value.

There are plenty of points that could be added to the economics of The Big Short if it was a film of more or less unlimited length:

Krugman and friends like the film because it leaves out any discussion of the main culprit behind the financial crisis, which was not Wall Street “greed” but bad monetary and credit policies from the Federal Reserve and the federal government. The movie barely hints at any exogenous factors behind the boom or bust. (This FEE report by Peter Boettke and Steven Horwitz fills in the missing information.) So the pro-regulation crowd is cheering. Viewers are given no understanding of the real causal factors and hence fill in the missing data with a feeling that banks just love ripping people off. To be sure, if you approach this movie with some knowledge of economics and monetary policy, the rest of the narrative makes sense. Of course Wall Street got it wrong, given Washington’s policies on mortgage lending!

To add to the brew, Edward Prescott points out the Great Recession can be explained through productivity shocks. Specifically, a collapse in investment and in particular investment in intangibles such as intellectual property in 2007 in anticipation of more taxes and more regulation.

The Great Recession had many of the same features of the 1990s technology boom but in reverse. The boom in the 1990s and bust in 2007 were somewhat inexplicable because major sources of volatility were unmeasured, specifically, investment in intangible capital.

V.V. Chari also points out that the extent of the financial crisis was overstated. This is because the typical firm can finance its capital expenditures from retained earnings so it was hard to see how financial market disruptions could directly affect investment.

What Chari disputed was that bank lending to non-financial corporations and individuals has declined sharply, that interbank lending is essentially non-existent; and commercial paper issuance by non-financial corporations declined sharply, and rates have risen to unprecedented levels.

John Taylor argues that we should consider macroeconomic performance since the 1960: There was a move toward more discretionary policies in the 1960s and 1970s; A move to more rules-based policies in the 1980s and 1990s; and back again toward discretion in recent years.

These policy swings are correlated with economic performance—unemployment, inflation, economic and financial stability, the frequency and depths of recessions, the length and strength of recoveries. Less predictable, more interventionist, and more fine-tuning type macroeconomic policies have caused, deepened and prolonged the current recession. Robert Hetzel puts it this way:

The alternative explanation offered here for the intensification of the recession emphasizes propagation of the original real shocks through contractionary monetary policy. The intensification of the recession followed the pattern of recessions in the stop-go period of the late 1960s and 1970s, in which the Fed introduced cyclical inertia in the funds relative to changes in economic activity.

Finn Kydland considers fiscal policy to be at the heart of the slow recovery. Instead of restructuring and investing more prudently, Western countries faced with budget shortfalls will seek to increase taxes:

Now imagine trying to incorporate all the above points into a film and keeping it at its current two-hour length?

31 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic history, fisheries economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: banking crises, financial crises, sovereign debt crises, sovereign defaults

24 Jan 2016 1 Comment

in applied price theory, business cycles, macroeconomics, unemployment

Elsby, Shin and Solon (2016) have published a paper throwing a spanner in the works for business cycle theories premised on downward wage rigidity:

We devote particular attention to the hypothesis that downward nominal wage rigidity plays an important role in cyclical employment and unemployment fluctuations. We conclude that downward wage rigidity may be less binding and have lesser allocative consequences than is often supposed.

Keynesian macroeconomics is premised on downward wage rigidity. There is mass unemployment during recessions because employers are unwilling or unable to cut wages.

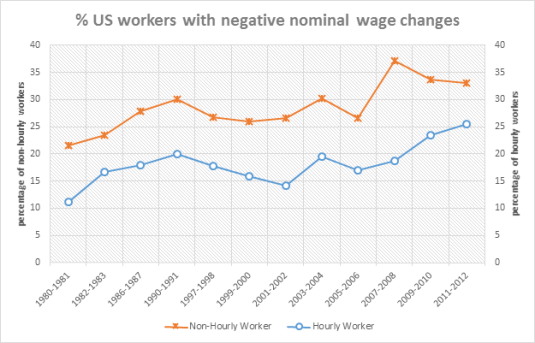

Elsby, Shin and Solon (2016) found that a non-trivial fraction of workers report nominal wage reductions: at least 10% of hourly workers and 20% of non-hourly workers. This fraction of workers whose nominal wage has been cut has been increasing since 1980 as shown in the chart below. The remaining workers either experienced a nominal wage freeze or a nominal wage increase in that year.

“What can wages and employment tell us about the UK’s productivity puzzle?” by Richard Blundell, Claire Crawford and Wenchao Jin found that in the recent British recession, 12% of employees in the same job as 12 months ago experienced wage freezes and 21% of workers in the same job as 12 months ago experienced wage cuts.

These results from the USA and UK come as no surprise to me because I have been on a collective employment agreement where after a restructuring, my pay was cut. The alternative was to leave and not receive a redundancy payment.

Chris Pissarides(2009), The Unemployment Volatility Puzzle: Is Wage Stickiness the Answer?, Econometrica argued the wage stickiness is not the answer to explaining unemployment since wages in new job matches are highly flexible:

1. wages of job changers are always substantially more procyclical than the wages of job stayers.

2. the wages of job stayers, and even of those who remain in the same job with the same employer are still mildly procyclical.

3. there is more procyclicality in the wages of stayers in Europe than in the United States.

4. The procyclicality of job stayers’ wages is sometimes due to bonuses, and overtime pay but it still reflects a rise in the hourly cost of labor

to the firm in cyclical peaks

I have been on several individual and collective agreements that grandfathered pay and conditions for existing workers and paid recruits less. I have lost count of the number of retirement pension scheme closed to new employees since I first encountered this cost saving practice at my first lecture at University.

My commercial law lecturer was explaining that he was lecturing part-time. His main job dealing with the litigation that might arise out of closing of the University retirement pension scheme. Some top-class academics had to retire earlier than they planned because of this closure to avoid a reduction in their pensions.

Most of my friends in the private sector are on bonus schemes were the great majority of the bonus is based on company profitability. Indeed, I know one company where everyone from the CEO down loses their bonus if there is a fatal workplace accident.

How can downward wage rigidity be a scientific hypothesis if the extensive international evidence of widespread nominal wage cuts wage cuts since the 1980s and 40%+ of the workforce on performance bonuses is not enough to refute it?

The same edition of the Journal of Labour Economics had a paper by Edward Lazear about how workplace effort varies with the business cycle and employment conditions:

…it seems that employers push their employees harder during recessions as they cut back the work force and ask each of the remaining workers to cover the tasks previously performed by the now-laid-off workers.

A number of models of long-term contracting in the labour market suggest that the level of employee effort expected varies with peak loads and general labour market conditions. That is understood from the start and is not is regarded as some form of opportunism by the employer after the contract is signed.

Likewise, employers do not lay off workers as soon as they become unprofitable in a downturn. If they did so, they would write off valuable firm specific human capital that might become profitable soon once the market recovers.

It is much easier to explain mass unemployment during a recessionas a a burst of layoffs at the beginning of the recession followed by the time it takes the unemployed to find suitable new vacancies and for employers to find it profitable to create such vacancies.

Some of these unemployed will simply wait for conditions to improve their existing industrial occupation so as to preserve their specialised human capital. These unemployed can be characterised as waiting unemployment or rest unemployment.

Other jobseekers will search further afield in new industries and occupations. These unemployed either have human capital that more general and mobile across many industries or have decided to scrap their industry specific and occupation specific human capital and try something else. The downturn in their current industry or occupation may be of sufficient duration that they regard waiting is a poor investment.

The economic concept of unemployment was rather primitive until Hutt write his hard to read theory of idle resources in 1939, Stigler’s paper in 1962 and the Phelps book in 1970.

I found Lucas and Prescott’s islands model to be an excellent explanation of unemployment. Lucas and Prescott’s economy is composed of a large number of scattered islands. Each of these islands is a one local labour market.

Workers in each of these islands have no precise knowledge of what wages will prevail in the economy outside of their own local labour market. Workers either remain on their island or leave it for what they expect to be a more alluring job further afield. Some workers are unemployed crossing between the islands, but they are nevertheless engaging in optimizing behaviour because they are looking for a better job than they have now.

Alchian (1969) lists three ways to adjust to unanticipated demand fluctuations:

• output adjustments;

• wage and price adjustments; and

• Inventories and queues (including reservations).

Alchian (1969) suggests that there is no reason for wage and price changes to be used regardless of the relative cost of these other options:

• The cost of output adjustment stems from the fact that marginal costs rise with output;

• The cost of price adjustment arises because uncertain prices and wages induce costly search by buyers and sellers seeking the best offer; and

• The third method of adjustment has holding and queuing costs.

There is a tendency for unpredicted price and wage changes to induce costly additional search. Long-term contracts including implicit contracts arise to share risks and curb opportunism over sunken investments in relationship-specific capital. These factors lead to queues, unemployment, spare capacity, layoffs, shortages, inventories and non-price rationing in conjunction with wage stability.

20 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, business cycles, economic growth, economic history, macroeconomics, monetary economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: CBI bias, inflation rate, measurement error, price indexes

1% to 1.5% is the usual estimate of bias in the consumer price index because of the introduction of new groups and quality upgrades in existing goods. I have adjusted the consumer price index inflation rate back to 1970 in New Zealand by 1.5% to see how long ago prices became stable. I know this is a rough adjustment, but it is still informative. If anything, the bias in the consumer price index from new goods and product upgrades is increasing rather than decreasing.

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

Prices have been stable or falling in New Zealand’s for at least three years now once bias in the consumer price index is taken into account. Despite this deflation, the economy seems to be getting along pretty well. There is also a long period of more or less stable prices in the 1990s once bias is taken into account in the measurement of consumer prices by the Statistics New Zealand.

11 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in business cycles, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, unemployment Tags: long-term unemployment

16 Dec 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, business cycles, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, occupational choice, personnel economics, theory of the firm

Jim Feyrer put forward a clever hypothesis about the sudden decline in the average quality of managers as a major contributor to the 1970s productivity slowdown. His hypothesis is a good contribution to real business cycle theory because what could be more random a shock than a demographic shock arising from the baby boom.

Feyrer’s hypothesis builds on Robert Lucas’s theory of the entrepreneur and the optimal size of the firm. The better entrepreneurs can manage larger spans of control.

Specifically, these more talented entrepreneurs can spread their skills and vision over a larger workforce thereby raising its productivity and that of the firm. Better quality managers are better trainers, better leaders, better problem solvers and better at recruiting and retaining staff.

If managerial skill and talent accumulates with experience, an influx of young workers into the workforce with the influx of the baby boomers into the workforce will lower the average quality of entrepreneurs. This will show up empirically as a decrease in the average age of managers and with that their experience and skills.

With the average age of the labour force lower during the influx of the baby boomers, more marginal managers have to be promoted into managerial positions to supervise younger employees. Lower managerial quality will lower the productivity of the workforce as a whole.

If managerial talent and skill is to have any meaning, a more talented manager should be able to extract greater productivity from the same quality labour force. Lazear points out that

Supervision and management are fundamental in personnel economics and in the theory of the firm… Boss effects are large and significant. Most important, bosses vary substantially in their quality. A very good boss increases the output of the supervised team over that supervised by a very bad boss by about as much as adding one member to the team.

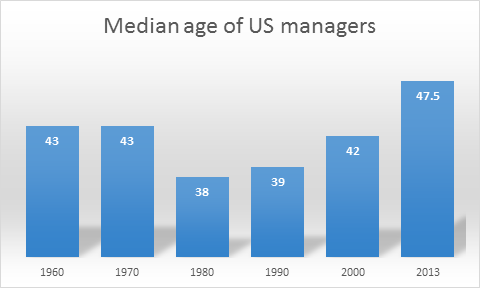

The influx of less able managers in the 1970s, as shown by a five-year reduction in the median age of US managers in the chart below, accounted for 20% of the observed productivity slowdown and resurgence in the 1970s and 1980s according to Feyrer. To fill vacancies, employers had to drop their hiring standards for managers.

Source: Jim Feyrer The US Productivity Slowdown, the Baby Boom, and Management Quality, Journal of Population Economics (2011) and Bureau of Labor Statistics Employed persons by detailed occupation and age (2013).

When the median age of managers rose in the 1990s, and along with it the average of quality of management, this productivity slowdown was reversed. Both the increase in the decrease in the age of managers are random productivity shocks in the tradition of real business cycle theory.

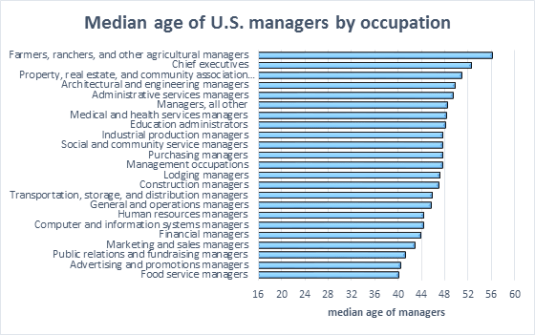

The average age of the US manager was 38 in 1980 and 39 in 1990. There is no US managerial occupation with an average age of less than 40 in 2013. The fifth managerial occupation with the lowest managing age is food service managers. The highest outside of agriculture is chief executives,

Source: Bureau of Labour Statistics Employed persons by detailed occupation and age (2013).

One of the mocking tones directed at real business cycle theory is it was supposed to require a regular forgetting of technologies so that productivity fell and then the loss technologies were remembered a few years later to have a business cycle.

That forgetting and remembering is what happened with the average age of managers and labour productivity in the 1970s. Management quickly lost five years of experience then slowly regained it with matching productivity swings and roundabouts.

Feyrer is another addition to a long line showing that business cycles can arise from the sum of random shocks, rather than one big shock, as Prescott suggested in 1986:

Another Summers question is, Where are the technology shocks? Apparently, he wants some identifiable shock to account for each of the half dozen postwar recessions. But our finding is not that infrequent large shocks produce fluctuations; it is, rather, that small shocks do, every period.

02 Dec 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, economic history, economics of regulation, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: adverse selection, bank panics, bank runs, banking crises, deposit insurance, economics central banks, financial crises, moral hazard, sovereign defaults

10 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic history, economics of regulation, Euro crisis, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics Tags: British economy, employment law, equilibrium unemployment rate, Eurosclerosis, France, Germany, Italy, labour market reforms, Margaret Thatcher, Thatchernomics, The British Disease

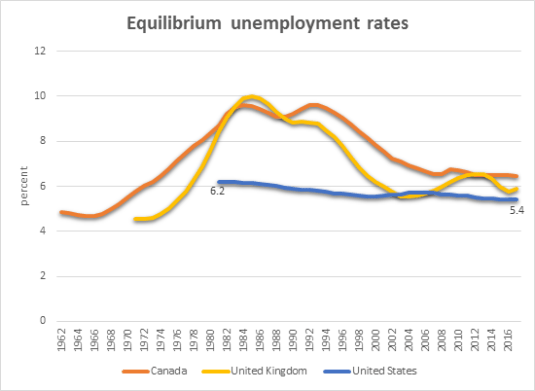

Unlike the USA, the German, Italian, British and French equilibrium unemployment rates all show fluctuations that reflect changes in their underlying economic circumstances and labour market reforms. The case of the British, the rise of the British disease and Thatchernomics. The case of German, its equilibrium unemployment rate rose after German unification and then fell after the labour market reforms of 2002 to 2005.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook November 2015 Data extracted on 10 Nov 2015 07:07 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

10 Nov 2015 2 Comments

in business cycles, economic history, macroeconomics, politics - USA, unemployment

The equilibrium unemployment rate in the USA has been dead flat at a little under 6% as far back as the OECD Economic Outlook November 2015 can estimate. The Canadian and British equilibrium unemployment rates have gone up and down to the point of near doubling at times. Institutions cannot be so stable in the USA and so unstable Canada and Britain in terms of the incentives to post vacancies, for search for work in the same in different industries and occupations and revise asking wages. We’re talking about a 35 year stretch macroeconomic and labour market policy in the USA.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook November 2015 Data extracted on 10 Nov 2015 07:07 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

Furthermore, there is a large literature in the early 1970s and late 1990s arguing that the US equilibrium unemployment rate dropped as low as 4%.

Source: Robert Shimer, Why is the U.S. Unemployment Rate So Much Lower? (1999).

More correctly, for the early 1970s literature, the equilibrium unemployment rate had risen to 4% after being at an equilibrium rate of about 3%. Something doesn’t add up.

Source: Robert Shimer, Why is the U.S. Unemployment Rate So Much Lower? (1999).

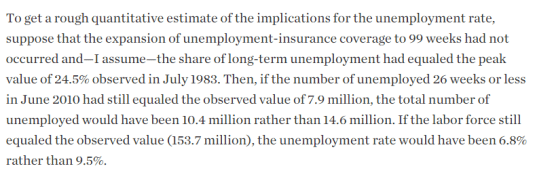

This estimate of an unchanging US equilibrium unemployment rate doesn’t add up even more when you consider the discussions after the Great Recession about how the extensions to unemployment insurance from a time limit of 26 weeks to 99 weeks would increase the equilibrium unemployment rate. Something really doesn’t add up for the US equilibrium unemployment rate to be so stable and the British and Canadian equilibrium unemployment rates to be so volatile.

Source: Robert Barro: The Folly of Subsidizing Unemployment – WSJ.

09 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic history, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: interest rates, monetary policy

15% and more. The long-term view on U.S. Nominal Interest Rates

(from 1.usa.gov/1V2PhP1) http://t.co/52o992NFhJ—

Max Roser (@MaxCRoser) September 20, 2015

03 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, macroeconomics, monetarism, monetary economics, politics - USA Tags: central banks, economics of central banking, monetary policy, rules and discretion, Taylor rule, The Fed

Yellen vs. Congress: The Fed's independence is under attack despite economic rebound bloom.bg/1HM9c0A http://t.co/NQ6548yGJK—

Bloomberg VisualData (@BBGVisualData) August 10, 2015

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments