Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

12 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, Austrian economics, business cycles, economic growth, F.A. Hayek, fiscal policy, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, unemployment, unions Tags: job search, mismatch unemployment, search unemployment, union power, union wage premium, waiting unemployment

11 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in human capital, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, law and economics, managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics, property rights, unemployment Tags: employment law, employment protection laws, employment regulation, firm-specific human capital, job search, labour market regulation, severance pay

There are a wide differences across the OECD in mandatory severance pay in the event of a layoff.

Source: Labor Market Regulation – Doing Business – World Bank Group.

Severance pay makes it more expensive to fire and therefore more expensive to hire. This means fewer job vacancies will be created but they will last longer.

The presence of mandatory severance pay could increase or reduce the unemployment rate but unemployment durations will increase because it takes longer to find a suitable job match among the fewer available vacancies.

Mandating severance pay does not make the job match inherently more profitable. It just redistributes some of the surplus from the job match to the end when it is terminated.

Employers and jobseekers may agree to severance pay where investments in firm specific and job specific human capital for the job is profitable.

Severance pay in these circumstances gives the employer and more reasons to invest in specific human capital. The promise to pay severance pay will make the employer hesitate to lay them off. The employer will instead retain them over a slack period or redeploy them within the company rather than pay them out. This pre-commitment encourages investment in firm specific and job specific human capital by both sides more secure, which makes the job match more profitable overall for both sides.

Of course, if it was possible to negotiate completely around severance pay mandated by law, there would be no effects on hiring, firing and unemployment durations. All it would mean is take-home pay would be less but in the event of a layoff, these employees would get that this wage reduction back as a lump sum.

29 Jan 2016 1 Comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, gender wage gap, marital division of labour, marriage and divorce

Geoff Simmons attributes part of the gender wage gap to the reluctance especially among women in high-paying jobs to haggle over pay. These women at the top end of the labour market are more likely to accept the first offer.

This relative reluctance of women to haggle over their pay is important to explaining why the gender wage gap is much larger at the top end of the labour market than at the bottom according to Geoff Simmons. Women have to haggle more if the gender pay gap is to close further.

Haggling over the wage has costs as well as benefits as Richard Epstein explained 20 years ago within a search and matching framework when commenting on a paper written by Carol Rose in 1992:

If one party is known to gobble up virtually all the cooperative surplus, then that party will find it difficult to attract deals. People anticipate getting some portion of the gain and will have a tendency to migrate to other individuals and transactions when they do not have to be ever watchful of their fair share of the gain.

If women have the characteristics that Rose attributes to them, then they would be able to enter more deals and find jobs more easily than men. At this point it becomes an empirical question: whether the greater frequency of deals (or shorter periods of unemployment) offset the tendency to gain a larger share of the profits of any given transaction.

Women will find it easier to get a job because they haggle less and therefore negotiations are less likely to breakdown, which will increase their lifetime income. This reduction in the cost of search because of a greater prospect of a match offset the losses in wages from successful haggling.

Indeed, does not this reluctance to haggle among women make it more likely that employers will hire women and promote the because their reluctance to haggle makes them cheaper. This starts off a competition between employers that will slowly drive up the wages offered to women.

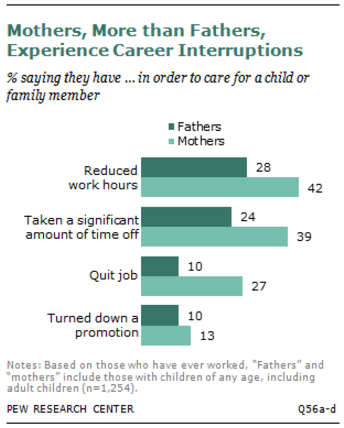

It is also the case that women invest in human capital that is more mobile between the jobs and they are more likely to quit the workforce and return again after motherhood.

The ability to quickly find a job after a career interruption is a competitive advantage rather than a disadvantage.

Men have more specialised human capital and are more likely to stay in one job so they have more to gain from haggling. In comparison, women invest in human capital that is more mobile between jobs because they anticipate downscaling or quitting because of motherhood.

In such a case, it is advantageous to have human capital that appeals to a wide range of employers and become can be quickly matched so that full-time or part-time employment and the associated income stream can start quick as quickly as possible. Workers who changed jobs more often and have shorter job tenures have less to gain and more to lose from haggling and not getting the job at all.

If women do not like to haggle, does this not imply they are less likely to be attracted the jobs with performance pay? Alan Manning investigated this specific question a few years ago.

The propensity of women to seek or avoid jobs with performance pay in a more competitive workplace is an important question because up to 40% of jobs have some form of performance pay which would put women off if they do not like to haggle as Geoff Simmons implies.

Manning used jobs with performance pay in the the 1998 and 2004 British Workplace Employees Relations Survey as a proxy for the level of competition in the workplace.

If Geoff Simmons is right, women should shy away from jobs with performance pay. Women should be less likely to hold these jobs with performance pay, other things being equal. That is precisely the hypothesis that Alan Manning explored. He is a world-class labour economist. What did he find?

We find very modest evidence for differential sorting into performance pay schemes by gender, and small effects of performance pay on hourly wages. Furthermore, and unlike the laboratory studies, we find no significant effect of the gender mix in the job on the responsiveness to performance pay.

We do find some evidence for an effect of performance pay on a measure of work effort in line with the experimental evidence but the bottom line is that a very small part of the gender pay gap can be attributed to these factors.

The gender pay is already tiny in New Zealand and only a tiny part of that can be explained as any reluctance of women to compete in the workforce such as through signing on for performance pay.

Manning found that the gender mix of jobs in occupation is not affected by the presence of performance pay but it should be if women are reluctant to angle and to be competitive as suggested by Geoff Simmons.

The reluctance of women to sign on for performance pay maybe be an aspect of the asymmetric marriage premium and the marital division of effort. Mothers, unlike fathers, cannot afford to go home at the end of the workday completely exhausted if there are children to care for.

Women have a long history of carefully selecting education and other human capital and occupations to anticipate the responsibilities of motherhood and minimising human capital depreciation during the associated career interruptions. Anticipating that motherboard is a lot of work is no stretch on that occupational sorting by women.

Women still do most of the household chores? Data on who does what in the house: goo.gl/3doqy4 #statistics https://t.co/fnY0d9OgkT—

DataStories (@LindaRegber) October 24, 2015

That division of effort between the sexes has got nothing to do with the behaviour of employers and everything to do with the marital division of labour. As to what to do about that Richard Posner raised a very good conundrum in a paper from 20 years ago:

The idea the government should try to alter the decisions of married couples on how to allocate time to raising children is a strange mixture of the utopian and the repulsive. The division of labour within marriage is something to be sorted out privately rather than made a subject of public intervention.

Liberal and radical frameless can if they wanted women to stay in the labour force and have no children or fewer children, or, persuade their husbands to assume a greater role in child rearing. Others can search the contrary. The ultimate decision is best left to private choice.

I remember from decades ago a couple at work who were very modern and trying to share the child rearing equally. Their three-year-old daughter was not very cooperative because she found that her mother was much better at braiding her hair than a father. That tantrum by their three-year-old was the beginning of the end of a grand plan.

18 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in job search and matching, labour economics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: Denmark, employment law, employment protection, labour market regulation

[Tweet https://twitter.com/KiwiLiveNews/status/688503382181449728 ]

Denmark is all the go in the New Zealand Labour Party as a model for labour market flexibility despite the fact that it is much more heavily regulated than either New Zealand or the USA.

07 Dec 2015 1 Comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, econometerics, gender, job search and matching, labour economics Tags: Armen Alchian, Gary Becker, gender wage gap, unconscious bias

Morgan Foundation researchers Jess Berentson-Shaw and Geoff Simmons were good enough to write a long reply to my recent post on the role of unconscious bias in the gender wage gap. My post was in reply to a Friday whiteboard session by Geoff Simmons.

I thought the best way to start is to summarise their reply in terms of how my rejoinder will be structured:

My reply to the original Friday whiteboard session by Geoff Simmons relied on invisible hand explanations. Nozick argued that invisible hand explanations of social phenomena must have a filter and an equilibrating mechanism.

Geoff Simmons’ hypothesis about the gender wage gap is an invisible hand explanation: 20-30% of the gender wage gap is driven by unconscious bias. There could be no greater an invisible hand than an unconscious one.

There must be a mechanism in Geoff Simmons’ hypothesis that guides market participants to not hire and not promote women on merit. Not hiring on merit forfeits profit. There must be a filter that penalise hiring on merit.

The market has a filter and an equilibrating mechanism that constitute its invisible hand. The equilibrating mechanism – the mechanism that prompts people to hire on merit – is price signals. Prices are a signal wrapped in an incentive. If prices go up, buy less and look for other options, if they go down, buying more is profitable. The filter, which is more of an invisible punch than an invisible hand, is profits and losses. Higher costs, lower profits, loss of market share, insolvency and bankruptcy drive out the entrepreneurs who fail to hire on merit.

Entrepreneurs that hire on merit are more likely to survive in market competition than those that do not. Entrepreneurs must adapt or die.

There is no similar institutional filter in Geoff Simmons hypothesis to ensure that not hiring on merit is the unintended outcome from the decentralised behaviour of countless employers and job seekers trying to improve their own circumstances. Self-interested employers are not prompted by price signals to not hire on merit. More importantly, their chances are surviving in market competition are increased rather than are reduced if employers resist the temptations arising from their unconscious biases against women.

This institutional context is the reverse of what should be for unconscious bias against women to survive in market competition as suggested by Geoff Simmons. Firms that hire on merit should have a lower probability of survival, not a higher chance of staying in business if the unconscious bias hypothesis is to prevail in the face of market competition.

Geoff Simmons and Jess Berentson-Shaw is they didn’t address my extensive comments about the market as an evolutionary process. They did not explain how market competition would not penalise employers who fail to hire on merit for any reason including unconscious bias. That is the fundamental flaw, a fatal flaw in their reply to my comment on their Friday whiteboard session.

Most of all, Geoff Simmons and Jess Berentson-Shaw succumb to what Robert Nozick christened normative sociology. This is the study of what the causes of social problems ought to be.

For Geoff Simmons and Jess Berentson-Shaw, the gender wage gap ought not be the result of the conscious choices of women making the best they can do what they have. The gender wage gap must be the result of the bad motivations of employers and other external forces. The bad motivations must be unconscious because conscious prejudice is rare these days.

The unconscious bias hypothesis suffers from the same floors as the occupational crowding and occupational segregation hypotheses. Neither the unintentional bias hypothesis nor the occupational crowding and segregation hypotheses have a filter and an equilibrating mechanism that guides employers into make unprofitable choices about hiring. These hypotheses must explain how unconsciously biased employers survive in competition with less unconsciously biased employers.

Central to Gary Becker’s theory of prejudice based discrimination is competition in the market will slowly wear down prejudice-based discrimination in the same way that it drives out any other practices inconsistent with profit maximisation and cost minimisation. Profit maximisation gets no respect in the theory of unconscious bias and the gender wage gap put forward by Geoff Simmons and Jess Berentson-Shaw.

If there are sufficient number of less unconsciously biased employers, there will be segregation. Some employers will hire a large number of women because they have the pick of the crop and will be more profitable to boot at least in the short run.

The more unconsciously biased employers will have a large number of men working for them and will be less profitable and more likely to fail. At worst, men and women will be paid to same but most women will work for these less unconsciously biased employers. The possibility of labour market segregation rather than gender wage gap was not considered in the unconscious bias hypothesis.

Unconscious bias is a preference-based explanation of the gender wage gap. The young are the last to notice the rapid social change that came before them. Cultural and preference based explanations underrate the rapid social change in the 20th century. As Gary Becker explains:

… major economic and technological changes frequently trump culture in the sense that they induce enormous changes not only in behaviour but also in beliefs. A clear illustration of this is the huge effects of technological change and economic development on behaviour and beliefs regarding many aspects of the family.

Attitudes and behaviour regarding family size, marriage and divorce, care of elderly parents, premarital sex, men and women living together and having children without being married, and gays and lesbians have all undergone profound changes during the past 50 years. Invariably, when countries with very different cultures experienced significant economic growth, women’s education increased greatly, and the number of children in a typical family plummeted from three or more to often much less than two.

Goldin (2006) showed that women adapted rapidly over the 20th century to changing returns to working and education as compared to options outside the market. Their labour force participation and occupational choices changed rapidly into long duration professional educations and more specialised training in the 1960s and 1970s as many more women worked and pursued careers. The large increase in tertiary education by New Zealand after 1990 and their move into many traditionally male occupations is another example.

The main drivers of the gender wage gap are unknown to recruiting employers such as whether a would-be recruit is married, how many children they have, whether their partner is present to share childcare, how many of children are under 12, and how many years between the births of children. Spacing out the births is a major driver of the gender pay gap but this information is unknown to employers when hiring. As Polachek explains:

The gender wage gap for never marrieds is a mere 2.8%, compared with over 20% for marrieds. The gender wage gap for young workers is less than 5%, but about 25% for 55–64-year-old men and women. If gender discrimination were the issue, one would need to explain why businesses pay single men and single women comparable salaries. The same applies to young men and young women.

One would need to explain why businesses discriminate against older women, but not against younger women. If corporations discriminate by gender, why are these employers paying any groups of men and women roughly equal pay? Why is there no discrimination against young single women, but large amounts of discrimination against older married women?

… Each type of possible discrimination is inconsistent with negligible wage differences among single and younger employees compared with the large gap among married men and women (especially those with children, and even more so for those who space children widely apart).

The main drivers of the gender wage gap are of no relevance to entrepreneurs making a profit. These findings are devastating to the notion that there is some sort of discrimination against women on the demand side of the labour market.

Employers lack the necessary information to implement any unconscious bias they might have against women in fact is mainly a bias against older women and mothers and mothers in particular the space out the births of their children. The emergence of the gender wage gap is through the supply-side choices of women because employers lack the necessary information to drive the emergence of a gender pay gap.

The career cost of a family is central to the emergence and size of the gender pay gap because it leads to self-selection on the supply-side in terms of human capital to mitigate the cost of careers breaks.

The gender gap is fairly minor before the age of 30. The female full-time employment rate drops by 10 percentage points after women enter their 30s before recovering by the time women reach the age of 50 (Johnston 2005). The gender wage gap also widens between the ages 35 to 64 when women are raising children; the biggest gap is for the ages of 44 to 44; a wage gap of 22 per cent (MWA 2010). The first child is estimated to reduce New Zealand female earnings by 7 per cent and second child reduces earnings by 10 per cent (Dixon 2000, 2001).

This self-selection of females into occupations with more durable human capital, and into more general educations and more mobile training that allows women to change jobs more often and move in and out of the workforce at less cost to earning power and skills sets. Chiswick (2006) and Becker (1985, 1993) then suggest that these supply side choices about education and careers are made against a background of a gendered division of labour and effort in the home, and in particular, in housework and the raising of children. These choices in turn reflect how individual preferences and social roles are formed and evolve in society.

Source: On Equal Pay Day, key facts about the gender pay gap | Pew Research Center.

Tiny differences in comparative advantage such as in child rearing immediately after birth can lead to large differences in specialisation in the market work and in market-related human capital and home production related work and household human capital (Becker 1985, 1993). These specialisations are reinforced by learning by doing where large differences in market and household human capital emerge despite tiny differences at the outset (Becker 1985, 1993).

Many women choose educational and occupational paths that give them more control over their hours worked, and lowers the cost of time spent on maternity leave and the associated depreciation of skills during career breaks and reduced hours (Polachek 1978, 1981; Bertrand, Goldin and Katz 2010; Katz 2006; Sasser 2005). Women over the entire run of the 20th century often end up in jobs that reduced the career cost of a family and rapidly changed their plans when new opportunities emerge (Katz 2006).

The prospect of children drives the early choices of women on education and occupations. Careers requiring continuous commitment, long hours and great sacrifices do not attract and retain as many women (Bertrand, Goldin and Katz 2010; Goldin 2006). Goldin and Katz (2011) found that differences in the reductions on the cost of career breaks was a major driver in the influx of women into previously male dominated occupations.

The key is what drives the rapid changes in the labour force participation and occupational choices of women. Some of the factors are global technology trends such rising wages and the emergence of household technologies and safe contraception and antidiscrimination laws. All of these increased the returns to working and investing in specialised education and training.

Up until the mid-20th century, women invested in becoming a teacher, nurse, librarian or secretary because these skills were general and did not deprecate as much during breaks. When expectations among women of still working at the age of 35 doubled, there were massive increases in female labour force participation and female investments in higher education and specialised skills (Goldin and Katz 2006).

In summary, Geoff Simmons and Jess Berentson-Shaw put forward an invisible hand explanation of the residual in the gender wage gap that lacks that all-important invisible punch. There is no market mechanism which penalises employers who rise above their unconscious bias against women to hire on merit. The invisible hand rewards employers that hire on merit with higher profits and penalises those that indulge a bias of whatever origin. The invisible hand consists of an invisible finger and an invisible punch. The invisible finger points the way forward through price signals; the invisible punch slaps down those entrepreneurs whose attentions wander from their bottom line when deciding who to hire and promote.

Part two of this reply will address the particulars of the reply of Geoff Simmons and Jess Berentson-Shaw. In particular, the search and matching aspects of their explanation and whether we are all sexists.

27 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, job search and matching, labour economics, unemployment

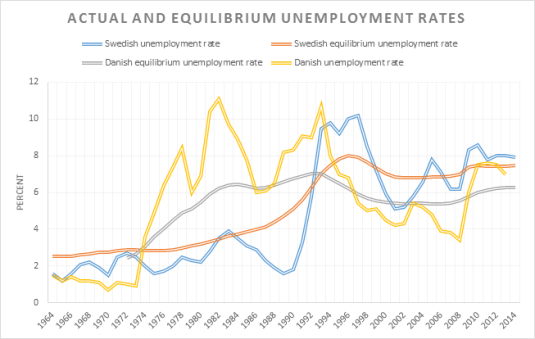

The Danish equilibrium unemployment rate has been surprisingly stable since 1982 despite rather volatile actual unemployment. The Swedish unemployment rate was allowed to increase in line with the economic crisis in the early 1990s and that was it. How nice it must be for the Danes and Swedes to have such stable labour market institutions.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook November 2015.

The Danes have a highly deregulated labour market. There were major economic and welfare state reforms in Sweden in the early 1990s in response to high unemployment. These institutional developments barely showed up in their equilibrium unemployment rates.

27 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, job search and matching, labour economics, unemployment

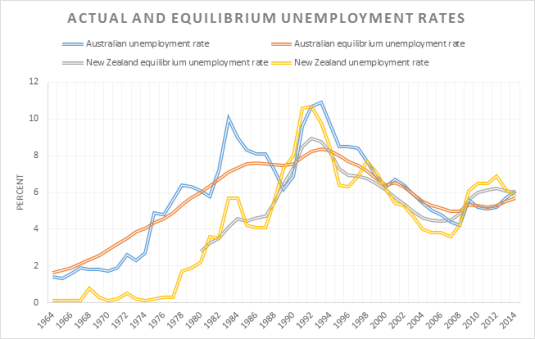

The Australian and New Zealand equilibrium unemployment rates are much more obedient. They neatly track actual unemployment with few exceptions for recessions. So much so is this close tracking of the actual unemployment rate by the equilibrium unemployment rate that you wonder what extra the latter concept adds.

Source: OECD Stat and OECD Economic Outlook November 2015.

26 Nov 2015 1 Comment

in economic history, job search and matching, unemployment

Unlike the USA, the OECD’s host country’s actual and equilibrium unemployment rates track each other rather too closely for comfort. In contrast, Italian unemployment hardly ever catches up with the Italian equilibrium unemployment rate. In common with the US equilibrium unemployment rate, the Italian equilibrium unemployment rate was rather stable for quite some time.

Source: OECD Stat and OECD Economic Outlook November 2015

26 Nov 2015 2 Comments

in economic history, job search and matching, labour economics, unemployment

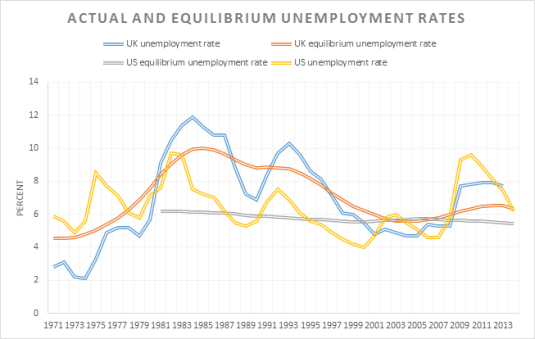

I can’t think of a charitable explanation of why the equilibrium unemployment rate is so stable in the USA and yet tracks actual unemployment with a bit of a lag in the UK. There is a large literature showing that the equilibrium unemployment rate in the USA has gone up and down quite significantly if only for demographic reasons related to the baby boomers passing through the workforce in large numbers in the 70s.

Source: OECD Stat and OECD Economic Outlook November 2015.

12 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, personnel economics, politics - New Zealand, unemployment, welfare reform

I stayed on after my Parliamentary testimony this morning to listen to others. A dozen or more made submissions arguing for more regulation – usually asking that zero hours contracts be outlawed.

I was the only submitter so far who argued against any regulation of zero hours contracts. I was thanked for putting a different perspective at the end of my submission. All members of the committee were very polite and listen to what I had to say.

Inadvertently, of course, Iain Lees-Galloway and Sue Moroney of the Labour Party and several members of the Public Service Association unearthed telling points against the case for regulation of zero hours contracts in the course of the morning in both the submissions and through the Q&A.

The first member of the Public Service Association to present information against zero hours contracts was a home support worker who was a union organiser.

This Public Service Association union organiser said, among many points in a kitchen sink submission, that zero hour contracts would deter people from entering her industry. That’s my point about zero hours contracts:

A second member of the Public Service Association talked about her daughter who was on a zero hours contract in her first job. After a seven-month spell of unemployment, her daughter worked as many shifts as possible to show she was a valued member of her team. Good for her. In low skilled jobs, what employers look for is someone who is friendly and reliable.

Part of that story was about the difficulties of her daughter with the correct payment of her unemployment benefit. Every Friday she has to telephone WINZ to forecast how many hours she expected to work in the following week so her unemployment benefit is correctly calculated for the following paid day.

From time to time, the submitter’s daughter was called in at the last minute for a shift on her zero hours contract at the weekend so that estimate of the previous day is incorrect and she is overpaid on her benefit.

This retention of unemployment benefit eligibility is a key point against the arguments raised by Iain Lee-Galloway about how workers and, in particular, the unemployed have no option but to accept zero hours contracts. Galloway was correct in making this the crux of the matter.

He can he kept stressing the inequality of bargaining power and a lack of options of job applicants when questioning me at the hearings this morning.

It was Iain Lees-Galloway who set up this bargaining power inequality as a crucial argument against zero hours contracts, not me. Zero hours contracts are said by the Labour Party and the unions to be a bad deal. It’s an offer job seekers cannot refuse, especially if they’re unemployed.

If beneficiaries do have options and they can refuse an offer of a zero hours contract, as 50% of British unemployment beneficiaries do, most arguments for the regulation or prohibition of zero hours contracts fall of the first hurdle.

The submitter’s daughter was still on an unemployment benefit despite taking a zero hours contract. She had options. She had a basic income, the unemployment benefit, so she was never left in the lurch if there was no shift that week. She never earned less than the unemployment benefit weekend and week out and often earned more.

The unemployment benefit allows beneficiaries to earn up to $200 a week after which benefit is withdrawn at 50 cents per dollar. As the beneficiary is still on the benefit, they have access to those all-important 2nd tier benefits ranging from accommodation allowances to special grants for unexpected urgent expenses.

Zero hours contracts allow the unemployed to make the benefit pay. Simon Chapple pointed out to me a few years ago that part-time work and benefit receipt can be an attractive long-term option for low skilled workers such as single mothers. The unemployment or single-parent beneficiary who works part-time has the certainty of the unemployment benefit plus a couple hundred dollars extra-week from their part-time job while retaining the second tier benefits that guard against unexpected expenses.

Sue Moroney then finished off the case against regulating zero hours contracts when questioning a submitter from the construction industry. The submitter was discussing the generosity of parental leave as well as zero hours contracts.

Sue Moroney pointed out that because of childcare responsibilities, the ability of that industry to attract women is greatly diminished if they offer zero hours contracts. She was pointing out a major cost of zero hours contracts to employers who offer them.

Sue Moroney highlighted the risk to employers of cutting themselves off from a major part of the job applicant pool – mothers of young children. That is a big cost unless employers offering zero hours contracts either pay a wage premium to keep access to that talent or offer these contracts to teenagers and adults, men and women, who circumstances dispose to working variable hours, sometimes working long hours and sometimes not working at all that week.

Zero hours contracts is an issue about job search and job matching. These contracts will benefit some employers and some employees. Other jobseekers will not sign such contracts. Still others will find that after signing a zero hours contract, that was not the best choice for them in retrospect. That form of on-the-job learning about competing job opportunities is common. Young people spend their first 10 to 15 years in the workforce job shopping. They move through half a dozen or more different jobs, employers and even industries before they find a good fit for them and stay on.

All in all, zero hours contracts empower the unemployed. Zero-hours contracts allow the unemployed to try out jobs while keeping their unemployment or single parent benefit. They don’t have to go completely off the benefit then risk a stand-down period of 6 to 12 weeks if they leave a regular job that is unsatisfactory.

Furthermore, the zero hours contracts give them an opportunity sometimes to earn a lot of money in a short period of time was still retaining their benefit eligibility. As another member of the Public Service Association mentioned when your wages balloon because of long hours one week, your benefit is wound back, but they are still on their benefit. They don’t have to reapply and risk of stand-down period

Zero hours contracts expand the options of jobseekers, especially the unemployed. Taking a zero hours contract gives the unemployed the option to test out a job without having to give up their unemployment benefit. They are empowering, not put upon as the Labour Party and the union members argued today.

10 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic history, economics of regulation, Euro crisis, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics Tags: British economy, employment law, equilibrium unemployment rate, Eurosclerosis, France, Germany, Italy, labour market reforms, Margaret Thatcher, Thatchernomics, The British Disease

Unlike the USA, the German, Italian, British and French equilibrium unemployment rates all show fluctuations that reflect changes in their underlying economic circumstances and labour market reforms. The case of the British, the rise of the British disease and Thatchernomics. The case of German, its equilibrium unemployment rate rose after German unification and then fell after the labour market reforms of 2002 to 2005.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook November 2015 Data extracted on 10 Nov 2015 07:07 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

01 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of media and culture, fiscal policy, industrial organisation, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, rentseeking, survivor principle Tags: film subsidies, Hollywood economics, industry policy, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge, unintended consequences

James Cameron is going to film the next three instalments of the Avatar franchise in New Zealand. He promises to spend at least NZ$500 million, employ thousands of Kiwis, host at least one red-carpet event, include a NZ promotional featurette in the Avatar DVDs, and will personally serve on a bunch of Film NZ committees, and probably even bring scones, all in return for a 25% rebate on any spending he and his team do in the country (up from a 20% baseline to international film-makers) that is being offered by the New Zealand Government.

The implication that many media reports are running with is that this is a loss to the Australian film industry, that we should be fighting angry, and that we should hit back at this brilliantly cunning move by the Kiwi’s by increasing our film industry rebates, which currently are about 16.5% (these include the producer and location offsets, and the post, digital and visual effects offset) to at very least 30%. These rebates cost tax-payers A$204 million in 2012, which hardly even buys you a car industry these days.

So what are the economics of this sort of industry assistance? Is this something we should be doing a whole lot more of? Was the NZ move to up the rebate especially brilliant? First, note that James Cameron has substantial property interests in New Zealand already, so this probably wasn’t as up for grabs as we might think. But if that’s how the New Zealand taxpayers want to spend their money, that’s up to them. The issue is should we follow suit?

The basic economics of this sort of give-away is the concept of a multiplier “”), which is the theory that an initial amount of exogenous spending becomes someone else’s income, which then gets spent again, creating more income, and so on, creating jobs and exports and all sorts of “economic benefits” along the way.

People who believe in the efficacy of Keynesian fiscal stimulus also believe in the existence of (>1) multipliers. Consultancy-based “economic impact” reports do their magic by assuming greater-than-one multipliers (or equivalently, a high marginal propensity to consume coupled with lots of dense sectoral linkages). With a multiplier greater than one, all government spending is magically transformed into “investment in Australian jobs”.

So the real question is: are multipliers actually greater-than-one? That’s an empirical question, and the answer is mostly no. (And if you don’t believe my neoliberal bluster, the progressive stylings of Ben Eltham over at Crikey more or less make the same point.)

But to get this you have to do the economics properly, and not just count the positive multipliers, but also account for the loss of investment in other sectors that didn’t take place because it was artificially re-directed into the film sector, which no commissioned impact study ever does.

This is why economists have a very low opinion of economic impact studies, which are to economics what astrology is to physics.

What does make for a good domestic film industry then? Look again at New Zealand, and look beyond the great Weta Studios in Wellington, for Australia and Canada both have world-class production studios and post-production facilities. Look beyond New Zealand’s natural scenery, for Vancouver is an easy match for New Zealand and Australia pretty much defines spectacular.

No, the simple comparison is that New Zealand is about 20% cheaper than Australia and 30% cheaper than Canada. New Zealand has lower taxes, easy employment conditions and relatively light regulations (particularly around insurance and health and safety). It’s just easier to get things done there.

If Australia really wants to boost its film industry, it might look more closely at labour market restrictions (including minimum wages) and regulatory burden and worry less about picking taxpayer pockets and bribing foreigners.

This article was originally published on The Conversation in December 2013. Read the original article. Republished under the a Creative Commons Attribution No Derivatives licence.

13 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, job search and matching, macroeconomics, unemployment

The unemployment rate was zero in New Zealand in 1956, 1957 and 1961. Apparently no one was jobless even for a day in New Zealand when changing jobs or entering or re-entering the workforce from outside employment, from school or other educational callings or as a migrant, if the OECD data is to be believed.

Data extracted on 13 Oct 2015 00:11 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

Unemployment was 1% for the rest of the 1960s in New Zealand before skyrocketing to 2.5% in 1975. By 1983, under the best of the good old days before the scourge of neoliberalism, unemployment rate had reached 5.5% after a steady increase from more than a decade.

The less than 1% unemployment was mostly under National Party rule but this era is looked upon with great fondness by the left-wing in New Zealand. Same in Australia where the good old days are known as the Menzies era: 23 years of Conservative party rule but beloved now by the left-wing as the ideal mixed economy.

Australian unemployment rates in the late 1960s was also pretty low given the requirements of labour market churn and entry on re-entry into the labour force.

13 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, job search and matching, macroeconomics, unemployment

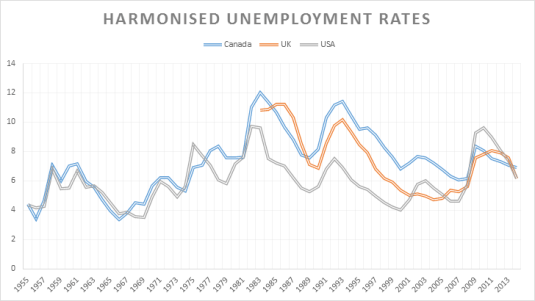

Canada has had much worse unemployment rates than the USA since the late 1970s. British unemployment rates have been doing okay since the late 1990s until the global financial crisis.

Data extracted on 13 Oct 2015 00:11 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments