From Paul Samuelson’s essay on marxist economics

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

03 May 2018 Leave a comment

in economics of crime, economics of information, environmental economics, financial economics, global warming, law and economics, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking Tags: climate alarmism, securities fraud

27 Apr 2018 Leave a comment

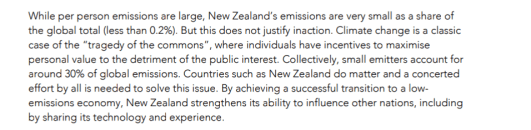

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, energy economics, environmental economics, global warming, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, public economics Tags: carbon pricing, carbon tax

27 Apr 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, energy economics, environmental economics, global warming, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking Tags: free riding, international public goods

24 Mar 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, development economics, economic history, growth disasters, growth miracles, international economics, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking, resource economics Tags: resource curse

10 Mar 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, development economics, economic history, fiscal policy, growth disasters, growth miracles, income redistribution, Public Choice, public economics Tags: Director's Law, growth of government, Steven Pinker, Wagner's Law

19 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

in fiscal policy, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: company tax

14 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

in politics - New Zealand, public economics

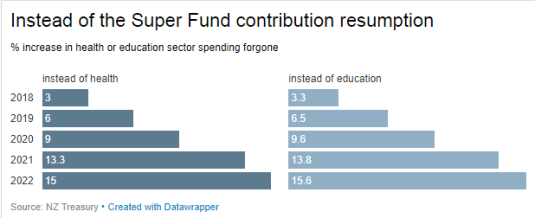

Would it have been cheaper just to raise the eligibility age to 67 for New Zealand superannuation? By 2022, either health or education spending could have been 15% higher.

14 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

in economic history, politics - USA, public economics Tags: top 1%

10 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

in economic history, politics - USA, public economics

26 Nov 2017 Leave a comment

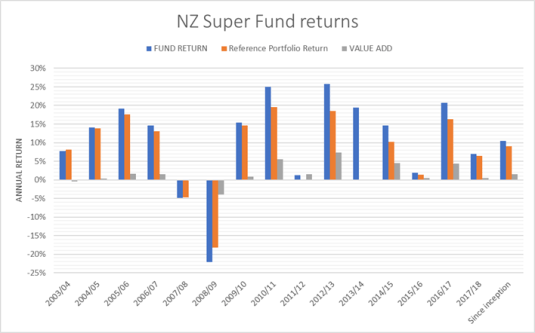

from https://www.nzsuperfund.co.nz/performance-investment/monthly-returns

Little wonder that no hedge fund headhunts from the New Zealand superannuation fund. Their staff turnover ratios are below 10% and often 5% and the CEO is paid a pittance by hedge fund standards.

Page 32 of "An Illustrated Guide to Income" more economic #dataviz at: bit.ly/12SEI9p http://t.co/HYm0II2UNI—

Catherine Mulbrandon (@VisualEcon) May 08, 2013

Page 33 of "An Illustrated Guide to Income" more economic #dataviz at: bit.ly/10M7lqR http://t.co/FcmaqZWB32—

Catherine Mulbrandon (@VisualEcon) May 09, 2013

21 Nov 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, energy economics, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, public economics

Source: Tol, Richard S J (2017) The structure of the climate debate. Energy Policy, 104. pp. 431-438.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments