When communism fell, so did mass killings. buff.ly/1PhbuYd #peace http://t.co/kZ3kKD3RI3—

HumanProgress.org (@humanprogress) August 11, 2015

Why are ex-Communists still on the Left forgiven for their past?

15 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, economics of crime, liberalism, Marxist economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: autocracy, communism, ex-Communists, genocide, mass murder, reigns of terror, tinpot dictatorships, totalitarian dictatorships

William Easterly on the Tyranny of Experts and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

13 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

Longest-serving (non-hereditary) world leaders

18 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, economic history, Public Choice Tags: autocracy

Where would Sepp Blatter rank among the longest-serving (non-hereditary) world leaders? bit.ly/1Fe5qZs http://t.co/O1Nvv7ytsx—

Guardian Data (@GuardianData) May 29, 2015

Gordon Tullock explains his theory of popular revolutions and palace coups

01 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of bureaucracy, Gordon Tullock, income redistribution, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: Arab Spring, autocracy, military coups, palace coups, popular revolutions

[I]n most revolutions, the people who overthrow the existing government were high officials in that government before the revolution.

If they were deeply depressed by the nature of the previous government’s policies, it seems unlikely that they could have given enough cooperation in those policies to have risen to high rank. People who hold high, but not supreme, rank in a despotism are less likely to be unhappy with the policy of that despotism than are people who are outside the government.

Thus, if we believed in the public good motivation of revolutions, we would anticipate that these high officials would be less likely than outsiders to attempt to overthrow the government.

From the private benefit theory of revolutions, however, the contrary deduction would be drawn. The largest profits from revolution are apt to come to those people who are (a) most likely to end up at the head of the government, and (b) most likely to be successful in overthrow of the existing government. They have the highest present discounted gain from the revolution and lowest present discounted cost.

Thus, from the private goods theory of revolution, we would anticipate senior officials who have a particularly good chance of success in overthrowing the government and a fair certainty of being at high rank in the new government, if they are successful, to be the most common type of revolutionaries.

Both Venezuelan and Singapore were ruled by socialist strongmen

30 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, growth disasters, growth miracles Tags: autocracy, capitalism and freedom, Singapore, Venezuela

Bad luck http://t.co/EaIoiqnjbR—

TakingHayekSeriously (@FriedrichHayek) March 28, 2015

Singapore’s Peoples Action Party was expelled from Socialist International in 1976. There is widespread government ownership of businesses in Singapore. So much so, that a new term was invented for it: Government Linked Corporations.

An essay on Lee Kuan Yew, the man who remade Asia on.wsj.com/1BR9YD4 http://t.co/hxG2p7ECpX—

David Crawshaw (@davewsj) March 28, 2015

Roger Congleton on why democracy emerged neither from revolutions nor the threat of revolution

06 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

Why all this sucking up to the dead Saudi dictator?

24 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in energy economics, industrial organisation, politics - Australia, politics - USA, resource economics Tags: autocracy, autocratic succession, cartel theory, creative destruction, David Friedman, M. A. Adelman, Middle-East politics, OPEC oil cartel

We are not living in the 70s, but nonetheless the death of the late unlamented Saudi dictator has flags at half-mast and other sycophantic behaviour that hasn’t been seen since the death of the last totalitarian dictator who was something of a player in geopolitics and American foreign policy.

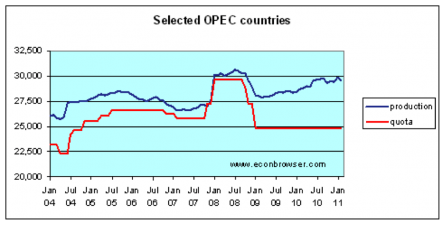

We are not living in the 70s where the West in fear of the OPEC cartel and the behaviour of Saudi Arabia as the swing producer and purported cartel enforcer.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2908448/oil_price_jan6.0.png)

OPEC and Saudi Arabia are both shadows of the former selves in terms of dominance in the global oil markets. OPEC as a whole represents about one third of global oil production, which was down for a little over 50% in 1973.

Within OPEC, Saudi Arabia As oil reserves that aren’t much bigger than those of either Iran or Venezuela. All of these countries, including Saudi Arabia have large populations and few other ways to servicing needs than from the oil revenues.

Russia is in the same position of needing to pump out as much oil as it can while letting someone else do the hard lifting regarding keeping the price of the oil up by cutting back production. US oil production has been on the rise, and has lessened the need for imported crude oil.

The best place to be in any cartel is outside the cartel selling as much as you can at the cartel price. The next best option is to be a cartel member, pretending to be a loyal while selling under the counter bias, much as you can. Recent discounts given by the Kingdom to some customers have been interpreted as showing a determination to maintain market share. David Friedman explains:

One great weakness of a cartel is that it is better to be out than in. A firm that is not a member is free to produce all it likes and sell it at or just below the cartel’s price.

The only reason for a firm to stay in the cartel and restrict its output is the fear that if it does not, the cartel will be weakened or destroyed and prices will fall.

A large firm may well believe that if it leaves the cartel, the remaining firms will give up; the cartel will collapse and the price will fall back to its competitive level.

But a relatively small firm may decide that its production increase will not be enough to lower prices significantly; even if the cartel threatens to disband if the small firm refuses to keep its output down, it is unlikely to carry out the threat.

Maurice Adelman regards the oil glut as the chronic condition of the world oil market, given the continuous tendency to underestimate reserves and undiscovered oil.

There was a glut 70 years ago, 50 years ago in 1933, 15 years ago in 1970 …But that condition of everlasting glut is periodically broken by dangers of oil shortage.

All cartels break-down and only some get back together. Cartels contain seeds of their own destruction. Cartel members are reducing their output below their existing potential production capacity, and once the market price increases, each member of the cartel has the capacity to raise output relatively easily. Adelman explains:

Opinions vary as to what is the right price for maximum profit, and opec has often had to find its right price through trial and error…

Each opec member could reap a windfall by cheating and producing over quota because the cost of production is so far below the market price. But, if some cartel members were to defect, output would climb and the prices — and windfall profits — would fall.

OPEC members pay scant regard to their actual production quotas and their national production quotas are always increased when push comes to shove. As Bill Allen said:

Long-term survival of the cartel has two fundamental requirements: first, cheating by a member on the stipulated prices, outputs and markets must be detectable; second, detected cheating must be adequately punishable without leading to a break-up of the cartel.

All cartels must decide how to allocate the reduction of output that follows the price increases across members with different costs structures and spare capacity.:

- The tendency is for cartel members to cheat on their production quotas, increasing supply to meet market demand and lowering their price.

- Most cartel agreements are unstable and at the slightest incentive they will quickly disband, and returning the market to competitive conditions.

The exercise of collective market power will not be stable unless sellers agree on prices and production shares; on how to divide the profits; on how to enforce the agreement; on how to deal with cheating; and on how to prevent new entry.

A cartel is in the unenviable position of having to satisfy everyone, for one dissatisfied producer can bring about the feared price competition and the disintegration of the cartel. Thus a successful cartel must follow a policy of continual compromise. Little wonder that John. S McGee wrote that:

The history of cartels is the history of double crossing.

Was it important to suck up to the Saudi dictator because of its role as swing producer in OPEC. In 1983, 1984, and 1986, for example, the Saudis produced only about 3.5 million barrels per day, despite their (then) production capacity of about 10 million barrels per day. Whatever else you can say about those production cutbacks to defend posted OPEC cartel price, they were a long time ago.

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates have large reserves relative to the financial needs of their population but what they have is only a small share of global reserves and global production of oil and trivial share if you add global shale production.

With the exception of the wake of the 1979 Iranian upheaval, and market anticipation of a possible destruction of substantial reserves in the 1990–1991 and 2003 Gulf wars, real prices of crude oil fell from 1974 through 2003. Prices increased in 2004 onwards because of demand in Asia.

Bryan Caplan summarised the views of leading oil economist James Hamilton in 2008 as follows:

1. OPEC has almost no effect on world oil prices; most countries produce less than their quota, and when countries want to produce more, their quota goes up.

2. The price of oil follows a random walk. But the oil industry isn’t trying very hard to develop new sources because oil execs believe that the price of oil is mean-reverting (i.e., what goes up must come down). Why are the oil execs so wrong? Hamilton’s guess: They’re putting too much weight on their last big experience with high oil prices in the 70s and 80s.

No amount of cutting can support prices when supply outside OPEC is growing strongly and demand is weak in the wake of the global financial crisis and the slower recoveries both in the USA and Europe. Hamilton’s current view is that:

…of the observed 45% decline in the price of oil, 19 percentage points– more than 2/5– might be reflecting new indications of weakness in the global economy.

Whatever reason people are sucking up to the dead Saudi dictator, they have nothing to do with the global oil market.

The Arab Spring – will there ever be a successful popular revolution?

23 Mar 2014 1 Comment

in Gordon Tullock, political change, Public Choice Tags: Arab Spring, autocracy, free-riders, military coups, people power, popular revolutions, succession crisis in politics

The Arab Spring is a good example of Gordon Tullock’s consideration of revolutions as palace coups that sometimes occur against the background of street protests. For Tullock, the puzzle is not that popular revolutions are so rare, but that they happen at all.

The role of street protests in the Arab Spring was to throw in the possibility of mutinies and desertions in the army and police. Previous alliances are thrown into doubt especially as the autocrat is old and sick, but had been for many years grooming his young son to inherit his power.

Ordinary citizens obey dictators because if they don’t, they are highly unlikely to make any difference in any revolt and could get killed during the uprising even if it succeeds. Worse awaits them if the revolt fails.

To stay in power, Tullock considers that an autocrat needs a moderately competent secret police willing to torture and kill, and a policy of rewarding generously those who betray coup plotters. Of course, the plotters must be shot.

Autocrats are fundamentally insecure. Wintrobe wrote of the “Dictator’s Dilemma” – the problem facing any ruler of knowing how much support he has among the general population, as well as among smaller groups with the power to depose him. Most dictators are overthrown by the higher officials of their own regime.

Most dictators do not anoint a formal successor while they are in office. Tullock argued that as soon as a likely successor emerges, loyal retainers start to form alliances with that person and may see private advantage in bringing his anointed day forward. Can’t have that.

More than a few autocrats were murdered in their sleep. To his very last day, Stalin locked his bedroom door because he did not trust the bodyguards who had been with him since the 1920s.

As for the populace, the autocrat must use both the carrot and the stick to buy loyalty. It is tricky to get the right mix of repression and co-optation due to lack of information. So dictators pay very high wages to select groups to secure their loyalty, especially the military and police. The communist party of the USSR started with 100,000 members in 1920. By the early 1980s, co-optation left it with 26 million members with the ensuing privileges.

Perfectly ordinary regular armed forces, with no counterinsurgency doctrine or training whatsoever, have in the past regularly defeated insurgents by using well-proven methods.

The simple starting point is that insurgents are not the only ones who can intimidate or terrorise civilians.

For instance, whenever insurgents are believed to be present in a village, small town, or city district, the local notables can be compelled to surrender them to the authorities, under the threat of escalating punishments, all the way to mass executions. That is how the Ottoman Empire controlled entire provinces with a few feared janissaries and a squadron or two of cavalry.

Terrible reprisals to deter any form of resistance were standard operating procedure for the German armed forces in the Second World War. Compare occupied France with the U.S. in Iraq:

- German officers walked around occupied France with no more than side-arms because any mischief would be dealt with by savage reprisals.

- American forces in Iraq bunker down and move in convoys because they do not launch reprisals.

On the side-lines, even better, watching it all on TV is the safest place for most to be in a popular revolution, uprising or insurgency.

Unless you control key military resources in the capital, what you do personally does not matter to the success of the revolution. Sticking your neck out can get you shot at or perhaps tortured. A classic ‘free rider’ dilemma.

If you must get involved, the best place to be in a mounting revolution is to be a ‘late switcher’. Switch sides when you are sure of joining the winning side. Back the winner just as he is about to win.

One reason for those post-revolution and post-coup purges is the small number of people actually involved in overthrowing the old autocrat and who actually stuck their necks out while plotting the coup do not trust their Johnny-come-lately new allies. They turn on these late-switchers before they change sides again to support a further coup of their own or a counter-coup.

People power in Manila in 1986 had a lot to do with late switching in a coup plot.

Originally, a military coup was planned by General Ramos and Defence Minister Enrile against the dying Marcos.

The coup plotters feared for their lives under Imelda. The plot was uncovered. Assassins were dispatched.

Ramos and Enrile gave up on forming a military junta and threw their lot with Cory Aquino and her popular movement in the hope that the army would split or hold off until the lay of the land was clearer, which the army did. That 1986 military coup and the coup attempts in succeeding years were staffed by different cabals of these late switchers.

Yeltsin on that tank in Moscow with a loud hailer was great TV, but remember he was calling for the army and security forces to switch sides or at least stay neutral. They did.

The mid-1980s Russian leaders were old and sick, so many ambitious younger army officers and nomenklatura saw their main chance if they boxed real clever and switched sides just at the right moment.

After every change of leadership in the USSR, there is a redistribution of patronage. Perestroika and Glasnost were, on closer inspection, another round of these reallocations of patronage. Patronage to their own entourages are routine for new autocrats throughout history.

Every Russian leader had his own reform initiatives after entering office and had periodic anti-corruption purges to redistribute the rents of high government offices and state-owned enterprise management positions to the up-and-comers he could trust more. Like Khrushchev, Gorbachev also wanted to transfer resources away from the military. Gorbachev went further and wanted to stop bleeding money and resources to the communist satellite states of Eastern Europe.

It also should be always remembered that Qadaffi got his main chance to take over when he was a mere Colonel Qadaffi leading a small group of junior officers. Colonels control strategic components of the military but are not as well paid as those in the autocrat’s inner circle.

Generals are often close to the leadership; their appointments are usually somewhat political and benefit from generous patronage from the autocrat. They have little to gain but their life to lose in a coup plot.

Enough military coups are led by more junior officers seizing their main chance. This make their generals nervous enough about their own survival in a colonels’ coup to strike first and displace the current autocrat before they are the next to be arrested and share his fate. There is then a post-coup realignment of patronage to buy off the junior officers.

Nasser did not believe that he, as a lieutenant-colonel, would be accepted by the Egyptian people and so he and the Free Officers Movement selected a general to be their nominal boss and lead the coup in 1952. Nasser did not become Prime Minister until 1954 after a spell as a minister and then as Deputy Prime Minister.

What appears to be a popular uprising is normally a split within the government. The Arab Spring, not by coincidence, occurred during a succession crisis in Egypt. President Mubarak has been very old and sick for a long time. Gamal Mubarak was old enough to covet the presidency but would have a large entourage of his own that would take many of the lucrative posts from his father’s retainers and courtiers.

A few autocrats call elections and retire abroad. The gratitude of the populace and the uncertain identity of his successors creates a big enough break in the traffic to allow the dictator to get to the airport alive.

Recent Comments