Economic freedom and British productivity

30 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic growth, macroeconomics Tags: British economy, Margaret Thatcher

French, German, British and US tax revenues as % of GDP, 1965 – 2013

28 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, politics - USA, public economics, taxation Tags: British economy, France, Germany, growth of government

Figure 1: Tax revenue as percentage of French, German, British and US GDP, 1965–2013

Source: OECD StatExtract.

Long-term unemployment by sex, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK and USA, 1968 – 2013

26 May 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, unemployment Tags: Australia, British economy, Canada

Trade union density, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK and USA, 1960–2012

25 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, labour economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, unions Tags: Australia, British economy, Canada, trade union density, union power, union wage premium

Minimum wage relative to average wage of full-time worker, UK, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia, 1960–2012

24 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: Australia, British economy, Canada

Figure 1: minimum wage relative to median wage in full-time worker, UK, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia, 1960 – 2012

Source: OECD StatExtract

Figure 2: minimum wage relative to mean wage in full-time worker, UK, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia, 1960 – 2012

Source: OECD StatExtract

French and German real GDP per capita as a percentage of British GDP per capita, 1820–2010

21 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history Tags: British economy, France, Germany

Figure 1: French and German real GDP per capita are as percentage of British GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1820 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

US and Canadian real GDP per capita as a percentage of British GDP per capita, 1800–2010

19 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic growth, economic history, macroeconomics, politics - USA Tags: British economy, Canada, convergence

Figure 1: US and Canadian real GDP per capita are as percentage of British GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1800 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

Colonial upstarts! British, American and Canadian real GDP per capita, 1775–2010

18 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic growth, economic history, macroeconomics Tags: British economy, Canada, convergence, industrial revolution

The USA only overtook Britain in per capita GDP per capita in purchasing power parity terms early in the 20th century. Canada overtook the mother country in the post-war period.

Figure 1: British, American and Canadian GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1775 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

Figure 2: British, American and Canadian GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1775 – 1870

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

Figure 3: British, American and Canadian GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1870 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

When did Down Under overtake the Mother Country? Real GDP Britain, Australia and New Zealand 1820–2010

17 May 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, economic growth, economic history, growth disasters, growth miracles, macroeconomics Tags: Australia, British economy, convergence, lost decades, Maddison database, New Zealand

Pretty quickly according to figure 1. Britain, Australia and New Zealand quickly had similar standards of living in the middle of the 19th century until about 1880. Australia was richer for about 20 years until the great Federation drought took the wind out of its sails.

Figure 1: British, Australian and New Zealand GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1820 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

New Zealand then broke away at the end of the Second World War from both Australia and UK. In the mid-1960s circumstances changed with Australia drifting ahead of the UK and New Zealand drifting away to a lower standard of living.

Figure 2: British and Australian GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1820 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

Figure 2 shows that from about 1960 until 1990 Australia was richer than the UK. After that, the growth dividend of Thatchernomics allowed the British to catch up again to the Australians.

Figure 3: British and New Zealand GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1820 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

Figure 3 shows that New Zealand was richer than the UK in the mid-20th century. The lost decades in New Zealand from 1974 to 1992 let the sick man of Europe overtake New Zealand before Thatchernomics caused a growth spurt in the UK to take the British well ahead.

Figure 4: Australian and New Zealand GDP per capita (1990 Int. GK$PPP), 1820 – 2010

Source: The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm 2013 version.

Figure 4 shows that New Zealand was richer than Australian in the first part of the post-war period. The divergence started with the onset of the lost decades in New Zealand in the early 1970s.

Is the Mother Country catching up with Down Under? Real GDP per working age New Zealander, British and Australian, detrended, 1956 –2013

15 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic growth, economic history, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand Tags: Australia, British economy, lost decades

Figure 1: Real GDP per New Zealander, British and Australian aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1956-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 2: Real GDP per New Zealander, British and Australian aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1.9 per cent detrended, 1956-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Good old days alert: 1950s Britain

12 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history Tags: British economy, good old days

In the early 1950s, two million British households had no electricity or gas, which meant cooking in ranges or on open fires and lighting by candles or oil lamps. As late as 1961, 15 percent of the households in the industrial city of Birmingham didn’t have exclusive use of a toilet, and 32 percent didn’t have their own fixed baths; nearly 20 percent of Manchester’s households lacked a hot-water tap—the percentage of working-class households living in these conditions was naturally higher.

The sick men of Europe? British and Irish unemployment rates, 1956–2013

09 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic growth, economic history, great depression, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, unemployment Tags: British economy, Celtic Tiger, Ireland, prosperity and depression, sick man of Europe, unemployment rates

Source: OECD StatExtract

Ireland and Britain justly earned the name the sick man of Europe in the 1980s. Irish unemployment was in the mid teens much of the 1980s because the Irish economy was in a great depression from 1973 to 1992.

Unemployed people are defined as those who report that they are without work, that they are available for work and that they have taken active steps to find work in the last four weeks. The ILO Guidelines specify what actions count as active steps to find work; these include answering vacancy notices, visiting factories, construction sites and other places of work, and placing advertisements in the press as well as registering with labour offices.

Two booms, two depressions: British and Irish real GDP detrended, 1955–2013

07 May 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, economic growth, economic history, entrepreneurship, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, macroeconomics Tags: British disease, British economy, Celtic Tiger, Ireland, prosperity and depression, sick man of Europe

Figure 1: Real GDP per British and Irish aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1955-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 2 detrends British real GDP growth since 1955 by 1.9% and Irish real GDP growth by 3.6%. The US real GDP growth in the 20th century is used as the measure of the global technological frontier growing at trend rate of 1.9% in the 20th century. The Irish economy is more complicated story because its growth rate in figure 2 was detrended at a rate of 3.6% because it was catching up from a very low base. Trend GDP growth per working age Irish for 1960-73 was 3.6 per cent (Ahearne et al. 2006).

Figure 2: Real GDP per British and Irish aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1.9 per cent detrended UK, 3.6% detrended Ireland, 1955-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

A flat line in figure 2 indicates growth at 1.9% for that year. A rising line in figure 2 means above-trend growth; a falling line means below trend growth for that year.

In the 1950s, Britain was growing quickly that the Prime Minister of the time campaigned on the slogan you never had it so good.

By the 1970s, and two spells of labour governments, Britain was the sick man of Europe culminating with the Winter of Discontent of 1978–1979. What happened? The British disease resulted in a 10% drop in output relative to trend in the 1970s, which counts as a depression – see figure 2 .

Prescott’s definition of a depression is when the economy is significantly below trend, the economy is in a depression. A great depression is a depression that is deep, rapid and enduring:

- There is at least one year in which output per working age person is at least 20 percent below trend; and

- there is at least one year in the first decade of the great depression in which output per working age person is at least 15 percent below trend; and

- There is no significant recovery during the period in the sense that there is no subperiod of a decade or longer in which the growth of output per working age person returns to rates of 2 percent or better.

The British disease in the 1970s bordered on a depression. There was then a strong recovery through the early-1980s with above trend growth from the early 1980s until 2006 with one recession in between in 1990. So much for the curse of Thatchernomics?

Figure 1 suggests a steady economic course in Ireland until the 1990s with a growth explosion growth with the Irish converged on British living standards up until the global financial crisis.

Figure 2 shows the power of detrending GDP growth and why Ireland was known as the sick man of Europe in the 1970s and 1980s with unemployment as high as 18% and mass migration again. The Irish population did not grow for about 60 years from 1926 because of mass migration.

Figure 2 shows that real GDP growth per working age Irish dropped below its 3.6 per cent trend for nearly 20 years from 1974 , but more than bounced back after 1992. The deepest trough was 18 per cent below trend and the final trough was in 1992 – see Figure 2.

The deviation from trend economic growth made the Irish depression from 1973 to 1992 comparable in depth and length to the 1930s depressions (Ahearne et al. 2006).

The Irish depression of 1973 to 1992 can be attributed to large increases in taxes and government expenditure and reduced productivity (Ahearne et al. 2006). There were two oil price shocks in the 1970s and many suspect Irish policy choices from 1973 to 1987.

There were three fiscal approaches: an aggressive fiscal expansion from 1977; tax-and-spend from 1981; and aggressive fiscal cuts from 1987 onwards. In the early 1980s, Irish CPI inflation at 21 per cent, public sector borrowing reached 20 per cent of GNP.

To rein in budget deficits, taxes as a share of GNP rose by 10 percentage points in seven years. The unemployment rate reached 17 per cent despite a surge in emigration. The rising tax burden raised wage demands, worsening unemployment. Government debt grew on some measures to 130 per cent of GNP in 1986 (Honohan and Walsh 2002).

From 1992, Ireland rebounded to resume catching-up with the USA. The Celtic Tiger was a recovery from a depression that was preceded by large cuts in taxes and government spending from the late 1980s (Ahearne et al. 2006). Others reach similar conclusions but avoid the depression word. Fortin (2002, p. 13) labelled Irish public finances in the 1970s and to the mid-1980s as a ‘black hole’.

Fortin (2002) and Honohan and Walsh (2002) disentangle the Irish recovery into a long-term productivity boom that had dated from the 1950s and 1960s, and a sudden short-term output and employment boom since 1993 following the late 1980s fiscal and monetary reforms.

Honohan and Walsh (2002) wrote of belated income and productivity convergence. The delay in income and productivity convergence came from poor Irish economic and fiscal policies in the 1970s and 1980s.

This was after economic reforms in the late 1950s and the 1960s that started a process of rapid productivity convergence after decades of stagnation and mass emigration; Ireland’s population was the same in 1926 and 1971. During the 1950s, up to 10 per cent of the Irish population migrated in 10 years.

In the 1990s, many foreign investors started invested in Ireland as an export platform into the EU to take advantage of a 12.5 per cent company tax rate on trading profits. Between 1985 and 2001, the top Irish income tax rate fell from 65 to 42 per cent, the standard company tax from 50 to 16 per cent and the capital gains tax rate from 60 to 20 per cent (Honohan and Walsh 2002).

What happened after the onset of the global financial crisis in Ireland and the UK are for a future blog posts.

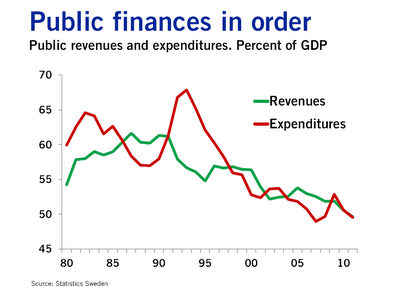

Swedosclerosis and the British disease compared, 1950–2013

03 May 2015 2 Comments

in economic growth, economic history, entrepreneurship, macroeconomics, Public Choice, public economics Tags: British disease, British economy, Margaret Thatcher, poor man of Europe, Sweden, Swedosclerosis, taxation and the labour supply, welfare state

In 1970, Sweden was labelled as the closest thing we could get to Utopia. Both the welfare state and rapid economic growth – twice as fast as the USA for the previous 100 years.

Of course the welfare state was more of a recent invention. Assar Lindbeck has shown time and again in the Journal of Economic Literature and elsewhere that Sweden became a rich country before its highly generous welfare-state arrangements were created

Sweden moved toward a welfare state in the 1960s, when government spending was about equal to that in the United States – less that 30% of GDP.

Sweden could afford to expand its welfare state at the end of the era that Lindbeck labelled ‘the period of decentralization and small government’. Swedes in the 60s had the third-highest OECD per capita income, almost equal to the USA in the late 1960s, but higher levels of income inequality than the USA.

By the late 1980s, Swedish government spending had grown from 30% of gross domestic product to more than 60% of GDP. Swedish marginal income tax rates hit 65-75% for most full-time employees as compared to about 40% in 1960. What happened to the the Swedish economic miracle when the welfare state arrived?

In the 1950s, Britain was also growing quickly, so much so that the Prime Minister of the time campaigned on the slogan you never had it so good.

By the 1970s, and two spells of labour governments, Britain was the sick man of Europe culminating with the Winter of Discontent of 1978–1979. What happened?

Sweden and Britain in the mid-20th century are classic examples of Director’s Law of Public Expenditure. Once a country becomes rich because of capitalism, politicians look for ways to redistribute more of this new found wealth. What actually happened to the Swedish and British growth performance since 1950 relative to the USA as the welfare state grew?

Figure 1: Real GDP per Swede, British and American aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1950-2013, $US

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 1 is not all that informative other than to show that there is a period of time in which Sweden was catching up with the USA quite rapidly in the 1960s. That then stopped in the 1970s to the late 1980s. The rise of the Swedish welfare state managed to turn Sweden into the country that was catching up to be as rich as the USA to a country that was becoming as poor as Britain.

Figure 2: Real GDP per Swede, British and American aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, detrended, 1.9%, 1950-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 2 which detrends British and Swedish growth since 1950 by 1.9% is much more informative. The US is included as the measure of the global technological frontier growing at trend rate of 1.9% in the 20th century. A flat line indicates growth at 1.9% for that year. A rising line in figure 2 means above-trend growth; a falling line means below trend growth for that year. Figure 2 shows the USA growing more or less steadily for the entire post-war period. There were occasional ups and downs with no enduring departures from trend growth 1.9% until the onset of Obamanomics.

Figure 2 illustrates the volatility of Swedish post-war growth. There was rapid growth up until 1970 as the Swedes converged on the living standards of Americans. This growth dividend was then completely dissipated.

Swedosclerosis set in with a cumulative 20% drop against trend growth. The Swedish economy was in something of a depression between 1970 and 1990. Swedish economists named the subsequent economic stagnation Swedosclerosis:

- Economic growth slowed to a crawl in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Sweden dropped from near the top spot in the OECD rankings to 18th by 1998 – a drop from 120% to 90% of the OECD average inside three decades.

- 65% of the electorate receive (nearly) all their income from the public sector—either as employees of government agencies (excluding government corporations and public utilities) or by living off transfer payments.

- No net private sector job creation since the 1950s, by some estimates!

Prescott’s definition of a depression is when the economy is significantly below trend, the economy is in a depression. A great depression is a depression that is deep, rapid and enduring:

- There is at least one year in which output per working age person is at least 20 percent below trend; and

- there is at least one year in the first decade of the great depression in which output per working age person is at least 15 percent below trend; and

-

There is no significant recovery during the period in the sense that there is no subperiod of a decade or longer in which the growth of output per working age person returns to rates of 2 percent or better.

The Swedish economy was not in a great depression between 1970 and 1990 but it meets some of the criteria for a depression but for the period of trend growth between1980 and 1986.

Between 1970 and 1980, output per working age Swede fell to 10% below trend. This happened again in the late 80s to the mid-90s to take Sweden 20% below trend over a period of 25 years.

Some of this lost ground was recovered after 1990 after tax and other reforms were implemented by a right-wing government. The Swedish economic reforms from after 1990 economic crisis and depression are an example of a political system converging onto more efficient modes of income redistribution as the deadweight losses of taxes on working and investing and subsidies for not working both grew.

The Swedish economy since 1950 experienced three quite distinct phases with clear structural breaks because of productivity shocks. There was rapid growth up until 1970; 20 years of decline – Swedosclerosis; then a rebound again under more liberal economic policies.

The sick man of Europe actually did better than Sweden over the decades since 1970. The British disease resulted in a 10% drop in output relative to trend in the 1970s, which counts as a depression.

There was then a strong recovery through the early-1980s with above trend growth from the early 1980s until 2006 with one recession in between in 1990. So much for the curse of Thatchernomics?

After falling behind for most of the post-war period, the UK had a better performance compared with other leading countries after the 1970s.

This continues to be true even when we include the Great Recession years post-2008. Part of this improvement was in the jobs market (that is, more people in work as a proportion of the working-age population), but another important aspect was improvements in productivity…

Contrary to what many commentators have been writing, UK performance since 1979 is still impressive even taking the crisis into consideration. Indeed, the increase in unemployment has been far more modest than we would have expected. The supply-side reforms were not an illusion.

John van Reenen goes on to explain what these supply-side reforms were:

These include increases in product-market competition through the withdrawal of industrial subsidies, a movement to effective competition in many privatised sectors with independent regulators, a strengthening of competition policy and our membership of the EU’s internal market.

There were also increases in labour-market flexibility through improving job search for those on benefits, reducing replacement rates, increasing in-work benefits and restricting union power.

And there was a sustained expansion of the higher-education system: the share of working-age adults with a university degree rose from 5% in 1980 to 14% in 1996 and 31% in 2011, a faster increase than in France, Germany or the US. The combination of these policies helped the UK to bridge the GDP-per-capita gap with other leading nations.

British economic recoveries compared

03 May 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, job search and matching, macroeconomics Tags: British economy, British general election, recessions and recoveries

Growth was good last year, will be okay in years to come. But overall? The slowest recovery in history #Budget2015 http://t.co/oMpkKpvIa1—

Fraser Nelson (@FraserNelson) March 18, 2015

Recent Comments