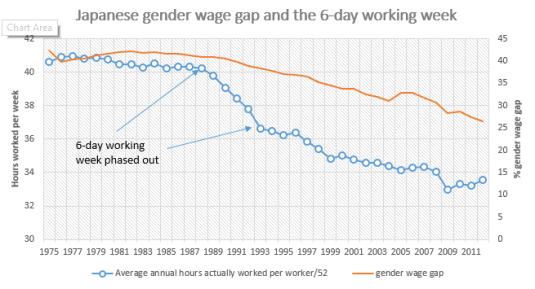

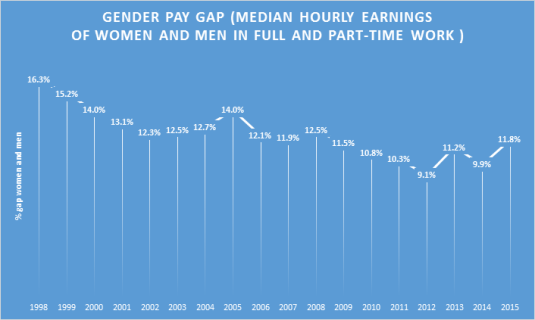

Geoff Simmons’ Friday Whiteboard podcast last night on the 12% gender wage gap was a good summary of the proximate drivers such as occupational segregation and part-time work. I have a few quibbles with his stress on unconscious bias as the driver of the gender wage gap.

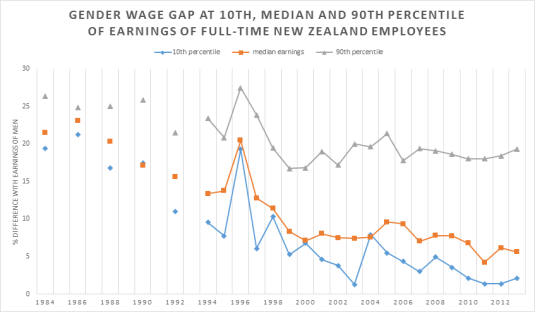

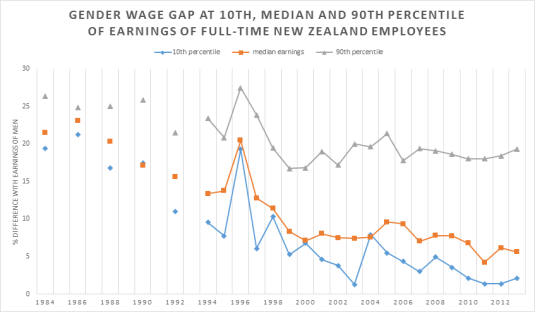

The first of these quibbles is the gender wage gap is tiny at the bottom and even the middle of the labour market but is so high and so stable for so long at the top-end. Why does unconscious bias increase with the wages on offer? Better paid professional women have far more options to look around for the best paid job and turned down inferior officers.

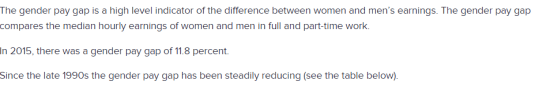

Source: OECD Employment Database.

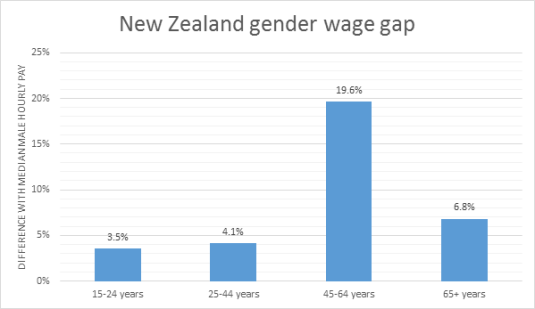

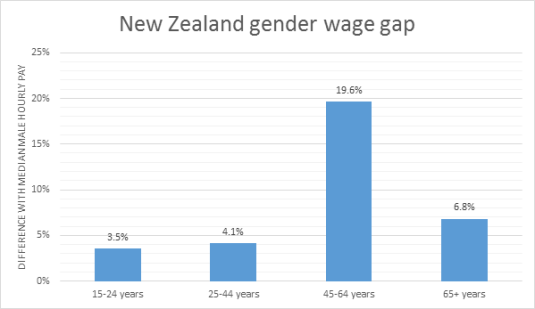

My second quibble is the New Zealand gender wage gap is trivial for women under the age of 45 but suddenly there is a burst of unconscious bias until they retire. This is odd because mature age workers have had plenty of time to accumulate human capital, search around for the best job offer and will have a job and therefore can turn down inferior offers. These women are not new starters on the unemployment benefit desperate for employment.

Source: New Zealand Income Survey 2014 via Human Rights Commission: Tracking Equality at Work.

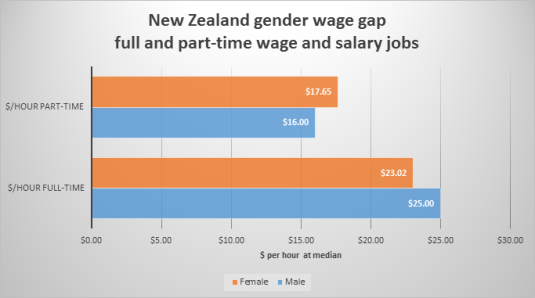

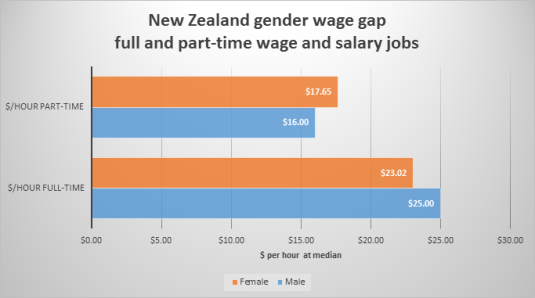

My final quibble is the gender wage gap for part-time workers is reversed. No one takes this higher pay per hour as evidence that there is no unconscious bias against women who work part-time. If the gender pay gap was in the opposite direction, of course, that pay gap would be conclusive evidence of unconscious bias against women in part-time jobs. But as the gap is as it is in favour of women not against them, the usual adjustments for skills, age and experience become convenient truths.

Source: Statistics New Zealand, New Zealand Income Survey, June quarter 2015.

Is what’s left of the unconscious bias hypothesis that we chauvinistic men, bastards all, have an unconscious bias against women who work full-time, who are over the age of 45 or earn a lot of money making us jealous?

The unconscious bias hypothesis for the residual in the gender wage gap has come to the fore because earlier hypotheses of deliberate discrimination against women fell by the wayside as explanations for the gender wage gap.

Complicating things is the unconscious bias hypothesis must explain why the unconscious bias is so much stronger at the top end of the labour market against women who have plenty of options to fight back including found in their own companies to hire women underpaid elsewhere.

As is well known, sex and race discrimination by employers as a profit opportunity for other less prejudiced employers including unconsciously prejudiced employers to hire the undervalued workers.

The process whereby the market bids up the wages of women undervalued by unconsciously biased employers can be itself be thoroughly unconscious as Armen Alchian explained in 1950. Alchian pointed out the evolutionary struggle for survival in the face of market competition ensured that only the profit maximising firms survived:

- Realised profits, not maximum profits, are the marks of success and viability in any market. It does not matter through what process of reasoning or motivation that business success is achieved.

- Realised profit is the criterion by which the market process selects survivors.

- Positive profits accrue to those who are better than their competitors, even if the participants are ignorant, intelligent, skilful, etc. These lesser rivals will exhaust their retained earnings and fail to attract further investor support.

- As in a race, the prize goes to the relatively fastest ‘even if all the competitors loaf.’

- The firms which quickly imitate more successful firms increase their chances of survival. The firms that fail to adapt, or do so slowly, risk a greater likelihood of failure.

- The relatively fastest in this evolutionary process of learning, adaptation and imitation will, in fact, be the profit maximisers and market selection will lead to the survival only of these profit maximising firms.

These surviving firms may not know why they are successful, but they have survived and will keep surviving until overtaken by a better rival. All business needs to know is a practice is successful. The reason for its success is less important.

In the case of unconscious bias against women, those employers who are less unconsciously biased than the rest will grow at the expense of less enlightened albeit unconsciously less enlightened rivals. Undervaluing workers for any reason is a business opportunity. The market processes will reduce this undervaluation. All that is required is that some employers be less unconsciously biased than others.

One method of organising production will supplant another when it can supply at a lower price (Marshall 1920, Stigler 1958). Gary Becker (1962) argued that firms cannot survive for long in the market with inferior product and production methods regardless of what their motives are. They will not cover their costs.

The more efficient sized firms are the firm sizes that are currently expanding their market shares in the face of competition; the less efficient sized firms are those that are currently losing market share (Stigler 1958; Alchian 1950; Demsetz 1973, 1976). Business vitality and capacity for growth and innovation are only weakly related to cost conditions and often depends on many factors that are subtle and difficult to observe (Stigler 1958, 1987). In the case of unconsciously biased employers, they are less likely to survive.

What is even more peculiar is this unconscious bias exists at the end of the market where there is the greatest incentive to invest in ascertaining the quality of recruits if Edward Lazear’s pioneering work on the personnel economics of hiring standards is to believed:

Screening is more profitable when the stakes are higher: The purpose of screening is to avoid the unprofitable candidates. Therefore, the greater the downside risk from hiring the wrong person, the more value there is to screening. Similarly, the longer that a new candidate can be expected to stay with the employer, the more valuable will be the screen. Firms that intend to hire employees for the long term thus tend to invest more in careful screening before committing to a new hire.

The higher the wage of recruit, the more important they are to the success of the firm. That gives the entrepreneur more reasons to sort and screen from better quality recruits. The higher paid is the recruit, the greater the returns to the applicant from signalling their quality:

Signalling is helpful when employers do not have enough information about job applicants to assess their potential accurately enough. It is useful when differences in talent among potential employees matter a lot to productivity. When differences in talent do not make much difference to productivity, signalling will not be very useful.

These ideas suggest when we should expect to see employment practices consistent with signalling. First, signalling should be more important in jobs where skills are most important. Such jobs tend to be those that are at high levels of the hierarchy, in research and development, and in knowledge work. They also correspond well to professional service firms, such as consulting, accounting, law firms, and investment banks. In such professions, even small differences in talent can lead to large differences in effectiveness on the job, so sorting for talent is very important. For this reason, such firms tend to screen very carefully at recruiting, and usually have promotion systems that correspond well to our probation story above, at least in the first few years on the job.

The presence of more unconscious bias at the top of the labour market than at the middle and the bottom doesn’t have as many legs as suggested by Geoff Simmons in his Friday podcast. The higher is the wage, the greater is investment by both sides to the recruitment equation in an unbiased consideration of the job application. This runs against the notion that the gender gap at the top end of the labour market is due to unconscious bias.

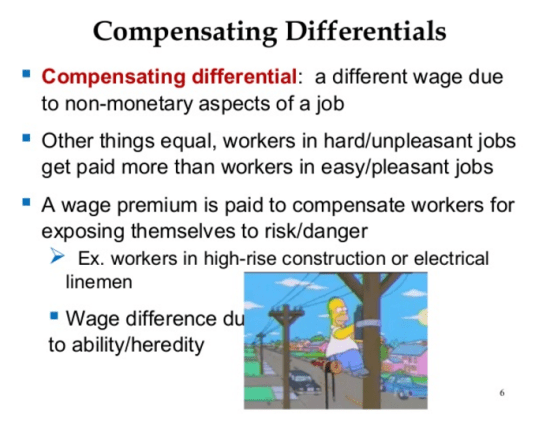

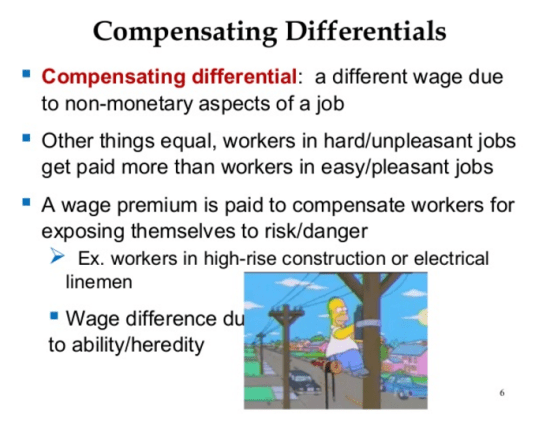

A far better explanation is compensating differentials. Women at the top are trading off wages from work-life balance and more time with their children. They can do so because they are well-paid.

Whatever the hypothesis about compensating differentials is, that hypothesis has nothing to do with unconscious bias by employers. Alison Booth and Jan van Ours were almost annoyed to find that British women are actually quite satisfied with part-time work:

Women present a puzzle. Hours satisfaction and job satisfaction indicate that women prefer part-time jobs irrespective of whether these are small or large but their life satisfaction is virtually unaffected by hours of work.

I will close with a quote from Amy Wax on the impractical nature of doing anything about unconscious bias:

Demonstrating racial bias is no easy matter because there is often no straightforward way to detect discrimination of any kind, let alone discrimination that is hidden from those doing the deciding. As anyone who has ever tried a job-discrimination case knows, showing that an organization is systematically skewed against members of one group requires a benchmark for how each worker would be treated if race or sex never entered the equation. This in turn depends on defining the standards actually used to judge performance, a task that often requires meticulous data collection and abstruse statistical analysis.

Assuming everyone is biased makes the job easy: The problem of demonstrating actual discrimination goes away and claims of discrimination become irrefutable. Anything short of straight group representation — equal outcomes rather than equal opportunity — is “proof” that the process is unfair.

Advocates want to have it both ways. On the one hand, any steps taken against discrimination are by definition insufficient, because good intentions and traditional checks on workplace prejudice can never eliminate unconscious bias. On the other, researchers and “diversity experts” purport to know what’s needed and do not hesitate to recommend more expensive and strenuous measures to purge pervasive racism. There is no more evidence that such efforts dispel supposed unconscious racism than that such racism affects decisions in the first place.

Recent Comments