How To Not Be Poor

01 Jul 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, poverty and inequality Tags: child poverty, economics of fertility, family poverty, marriage and divorce

Why is the Swedish gender wage gap so stubbornly stable (and high)?

06 May 2017 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: economics of fertility, female labour force participation, gender wage gap, maternity leave, preference formation, statistical discrimination, Sweden, unintended consequences

The Swedes are supposed to be in a left-wing utopia. Welfare state, ample childcare and long maternity leave but their gender wage gap is almost as bad as in 1980. They must be a misogynist throwback.

Maybe Megan McArdle can explain:

There are countries where more women work than they do here, because of all the mandated leave policies and subsidized childcare — but the U.S. puts more women into management than a place like Sweden, where women work mostly for the government, while the private sector is majority-male.

A Scandinavian acquaintance describes the Nordic policy as paying women to leave the home so they can take care of other peoples’ aged parents and children. This description is not entirely fair, but it’s not entirely unfair, either; a lot of the government jobs involve coordinating social services that women used to provide as homemakers.

The Swedes pay women not to pursue careers. The subsidies from government from mixing motherhood and work are high. Albrecht et al., (2003) hypothesized that the generous parental leave a major in the glass ceiling in Sweden based on statistical discrimination:

Employers understand that the Swedish parental leave system gives women a strong incentive to participate in the labour force but also encourages them to take long periods of parental leave and to be less flexible with respect to hours once they return to work. Extended absence and lack of flexibility are particularly costly for employers when employees hold top jobs. Employers therefore place relatively few women in fast-track career positions.

Women, even those who would otherwise be strongly career-oriented, understand that their promotion possibilities are limited by employer beliefs and respond rationally by opting for more family-friendly career paths and by fully utilizing their parental leave benefits. The equilibrium is thus one of self-confirming beliefs.

Women may “choose” family-friendly jobs, but choice reflects both preferences and constraints. Our argument is that what is different about Sweden (and the other Scandinavian countries) is the constraints that women face and that these constraints – in the form of employer expectations – are driven in part by the generosity of the parental leave system

Most countries have less generous family subsidies so Claudia Goldin’s usual explanation applies to their falling gender wage gaps

Quite simply the gap exists because hours of work in many occupations are worth more when given at particular moments and when the hours are more continuous. That is, in many occupations earnings have a nonlinear relationship with respect to hours. A flexible schedule comes at a high price, particularly in the corporate, finance and legal worlds.

Gender pay gap shown to be a myth by @paulabennettmp @women_nz

03 May 2017 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, law and economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: conspiracy theories, economics of fertility, gender wage gap, implicit bias, unconscious bias

The Minister for Women Paula Bennett and the Ministry of Women published excellent research in February showing there cannot be a gender wage gap driven by unconscious bias. The Minister has blamed a large part of the remaining gender wage gap on unconscious bias.

… up to 84 per cent of the reason for the Pay Gap, that’s right, 84 per cent, is described as ‘unexplained factors.’ That means its bias against women, both conscious and unconscious.

It’s about the attitudes and assumptions of women in the workplace, it’s about employing people who we think will fit in – and when you have a workforce of men, particularly in senior roles then it seems likely you’re going to stick with the status quo – whether they do that intentionally or just because “like attracts like”.

It’s because there is still a belief that women will accept less pay than men – they don’t know their worth and aren’t as good at negotiating.

The reason why this February 2017 research on the motherhood penalty contradicts earlier Ministry of Women research on unconscious bias and the gender wage gap is simple.

There is a large difference in the gender wage gap from mothers and for other women. As the adjacent graphic from Ministry of Women research shows, the gender wage gap for mothers is 17% but it is only 5% from other women.

Source: Effect of motherhood on pay – summary of results Statistics New Zealand and Ministry of Women February 2017.

We men, us dirty dogs all, have no way of knowing whether a female applicant is a mother. Remember we are dealing with unconscious bias, the raised eyebrow, the prolonged pause, the lingering glance, not a conspiracy or a prejudice of which we are self-aware and take overt steps to implement. Unconscious bias is unconscious by definition.

Because the bias against women is implicit and unconscious, we men, dirty dogs all, do not know we are biased, so we do not know we have to make further enquiries to check if the female applicant is a mother so we can discriminate against her more than we do for other women.That is before we consider other drivers of the gender wage gap such as whether there are relatively large spaces between the births of her children.

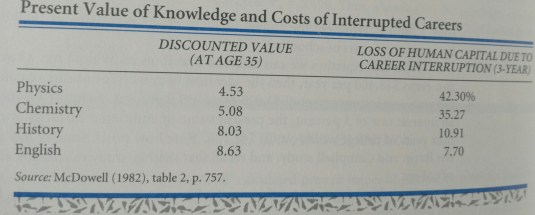

Large spaces between the birthdays of children greatly increases the gender wage gap because women spend much more time out of the workforce and part-time if they spread births. This reduces their accumulation of on-the-job human capital and encourages women who plan large families to choose occupations and educational majors that do not depreciate rapidly during career interruptions.

I have no idea how an unconsciously biased employer can discover if a woman has children with spaced out ages and therefore discriminate against an even more, unconsciously, of course. We men, dirty dogs all, do not know that in order to discriminate against them, especially in shortlisting for initial hiring when we have no information beyond the application about them.

Do women have more unconscious bias against women than men? If not, there should be differences in the gender pay gap in firms with more women managers or owners.

Becoming a mother and going part time is seriously bad for women's incomes ft.com/content/94e2e7… https://t.co/2bFfELztnX—

Chris Giles (@ChrisGiles_) August 23, 2016

Perhaps there is more unconscious biased in promotions because managers may have accidentally learnt are the ages of the children of female applicants and unconsciously taken a note to remember that when unconsciously discriminating against them in promotion. This unconscious bias involves a lot of very conscious data collection and retention.

All in all, the unconscious bias hypothesis simply cannot explain such a large difference between the gender wage gaps of parents and non-parents. There is too much evidence whose existence that is strictly forbidden by the hypothesis of unconscious bias against women in the workplace.

The case against an immigration economics and for a population economics

28 Apr 2017 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, politics - New Zealand, population economics Tags: economics of fertility, economics of immigration

Source: The case for immigration – Vox.

The traditional drivers of occupational segregation

23 Apr 2017 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: economics of fertility, female labour force participation, female labour supply, gender wage gap, marriage and divorce, occupational segregation

The main drivers of female occupational choice are supply-side (Chiswick 2006, 2007). This self-selection of females into occupations with more durable human capital, and into more general educations and more mobile training that allows women to change jobs more often and move in and out of the workforce at less cost to earning power and skills sets.

Chiswick (2006) and Becker (1985, 1993) then suggest that these supply side choices about education and careers are made against a background of a gendered division of labour and effort in the home, and in particular, in housework and the raising of children. These choices in turn reflect how individual preferences and social roles are formed and evolve in society.

These adaptations of women to the operation of the labour market, in turn, reflect a gendered division of labour and household effort in raising families and the accidents of birth as to who has these roles (Chiswick 2006, 2007; Becker 1981, 1985, 1993).

The market is operating fairly well in terms of rewarding what skills and talents people bring to it in light of a gendered division of labour and household effort and the accidents of birth. The issue is one of distributive justice about how these skills and family commitments are allocated and should be allocated outside the market between men and women when raising children. As in related areas such as racial and ethnic wage and employment gaps, these gaps are driven by differences in the skills and talents that people acquired prior to entering the labour market. …

Shock, horror! Chinese government statistics are unreliable

14 Apr 2017 Leave a comment

in development economics, population economics Tags: China, communist party, economics of fertility, one child policy, Population demographics

My Chinese friends at a Japanese university in 1995 must have been born in the 1970s at the height of the one child policy but always had a younger brother if the first child was female.

The way to tell whether the Chinese student was the daughter of a party member was to ask if they had any brothers or sisters.

How did the industrial revolution impact family planning? | Robert E. Lucas

17 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, development economics, economic history, history of economic thought, labour economics, macroeconomics, Robert E. Lucas Tags: economics of fertility, industrial revolution

TV and Indian fertility

01 Sep 2016 2 Comments

in development economics, economics, growth miracles, population economics Tags: economics of fertility, India

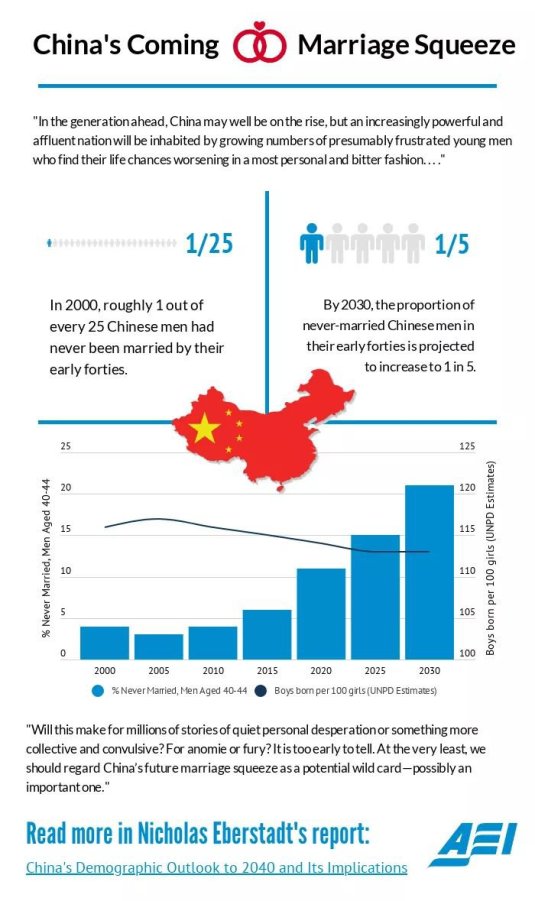

Without one-child policy, China still might not see baby boom, gender balance

03 Jul 2016 Leave a comment

in development economics, economic history, population economics Tags: China, economics of fertility

World, high income, middle income and low income country fertility rates since 1950

28 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in development economics, population economics Tags: demographic transition, economics of fertility, The Great Escape

Source: United Nations

Recent Comments