It is ironic that both camps use World War II as evidence that the fiscal policy might work (Keynesian macroeconomics) or it does not work (Barro and Ohanian).

The nature of the new spending and how it was financed both matter, as does whether the new spending was a public good, a private good or a general or contingent income transfer matter, and whether the new spending was tax or bond financed all matter to the income and substitution effects of taxes and the additional public debt.

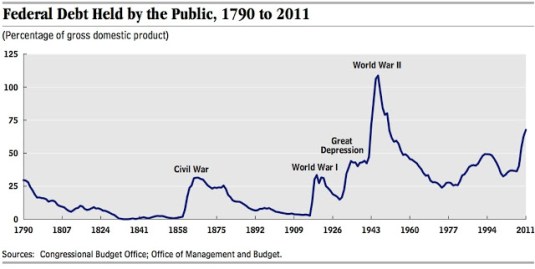

World War II was a temporary increase in government military purchases that will be followed by a long period of primary budget surpluses and perhaps surprise spikes in price inflation to pay down the massive wartime debt.

- A military build-up financed by debt lowers consumer wealth which induces households to consume less leisure and work more while the temporary nature of the fiscal shock increases labour input through inter-temporal substitution of labour into the period of lower taxes.

- The increase in the supply of labour leads to a fall in productivity and real wages. Inter-temporal substitution of labour also raises the real interest rate and lowers private investment.

Barro found that World War II U.S. defence expenditures increased by $540 billion per year at the peak in 1943-44, amounting to 44% of real GDP. this increased real GDP by $430 billion per year in 1943-44 – a multiplier was 0.8 (430/540). The main declines were in private investment, non-military government purchases, and net exports. Wartime production was a dampener, rather than a multiplier.

The war-based multiplier of 0.8 overstates the multiplier that would apply to peacetime government purchases. Public spending crowds out private spending wartime because of intertemporal substitution of labour and consumption smoothing so private investment falls substantially.

People expect the added wartime spending to be temporary so consumer demand will fall by less. Consumers saving less to smooth out the changes in consumption relative the changes in their current after-tax income if the war is expected to last no more than a few years and no major destruction of capital stock and population is anticipated.

Korean War expenditures were financed mostly by higher taxes resulted in a much lower output and welfare compared to the tax smoothing policy for World War II.

The US borrowed heavily to finance World War II as did for most of its previous wars. This means the tax rises necessary to pa for the war debt were spread over a much longer period of time and would in consequence have less effect on labour supply and investment.

In the Korean War, taxes were increased immediately to finance the war. In consequence,labour supply and investment dropped immediately during the period of high taxes

Britain taxed capital income at a much higher rate than the United States during the war and for much of the post-war period. Lee Ohanian explains what happened:

British capital income tax rates rose substantially during the war—they approached 90 per cent—and remained high after it.

Not surprisingly, savings and investment were close to zero over this period, reflecting the very low after-tax return to savings.

In time, London reduced tax rates on savings and investment—and, as a result, savings and investment began to rise, increasing from about 3 per cent of British GDP in the early 1950s to 20 per cent of GDP in the 1980s.

But before its capital income tax rates fell, the United Kingdom was among the slowest growing countries in the industrialized West.

Recent Comments