We are not living in the 70s, but nonetheless the death of the late unlamented Saudi dictator has flags at half-mast and other sycophantic behaviour that hasn’t been seen since the death of the last totalitarian dictator who was something of a player in geopolitics and American foreign policy.

We are not living in the 70s where the West in fear of the OPEC cartel and the behaviour of Saudi Arabia as the swing producer and purported cartel enforcer.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2908448/oil_price_jan6.0.png)

OPEC and Saudi Arabia are both shadows of the former selves in terms of dominance in the global oil markets. OPEC as a whole represents about one third of global oil production, which was down for a little over 50% in 1973.

Within OPEC, Saudi Arabia As oil reserves that aren’t much bigger than those of either Iran or Venezuela. All of these countries, including Saudi Arabia have large populations and few other ways to servicing needs than from the oil revenues.

Russia is in the same position of needing to pump out as much oil as it can while letting someone else do the hard lifting regarding keeping the price of the oil up by cutting back production. US oil production has been on the rise, and has lessened the need for imported crude oil.

The best place to be in any cartel is outside the cartel selling as much as you can at the cartel price. The next best option is to be a cartel member, pretending to be a loyal while selling under the counter bias, much as you can. Recent discounts given by the Kingdom to some customers have been interpreted as showing a determination to maintain market share. David Friedman explains:

One great weakness of a cartel is that it is better to be out than in. A firm that is not a member is free to produce all it likes and sell it at or just below the cartel’s price.

The only reason for a firm to stay in the cartel and restrict its output is the fear that if it does not, the cartel will be weakened or destroyed and prices will fall.

A large firm may well believe that if it leaves the cartel, the remaining firms will give up; the cartel will collapse and the price will fall back to its competitive level.

But a relatively small firm may decide that its production increase will not be enough to lower prices significantly; even if the cartel threatens to disband if the small firm refuses to keep its output down, it is unlikely to carry out the threat.

Maurice Adelman regards the oil glut as the chronic condition of the world oil market, given the continuous tendency to underestimate reserves and undiscovered oil.

There was a glut 70 years ago, 50 years ago in 1933, 15 years ago in 1970 …But that condition of everlasting glut is periodically broken by dangers of oil shortage.

All cartels break-down and only some get back together. Cartels contain seeds of their own destruction. Cartel members are reducing their output below their existing potential production capacity, and once the market price increases, each member of the cartel has the capacity to raise output relatively easily. Adelman explains:

Opinions vary as to what is the right price for maximum profit, and opec has often had to find its right price through trial and error…

Each opec member could reap a windfall by cheating and producing over quota because the cost of production is so far below the market price. But, if some cartel members were to defect, output would climb and the prices — and windfall profits — would fall.

OPEC members pay scant regard to their actual production quotas and their national production quotas are always increased when push comes to shove. As Bill Allen said:

Long-term survival of the cartel has two fundamental requirements: first, cheating by a member on the stipulated prices, outputs and markets must be detectable; second, detected cheating must be adequately punishable without leading to a break-up of the cartel.

All cartels must decide how to allocate the reduction of output that follows the price increases across members with different costs structures and spare capacity.:

- The tendency is for cartel members to cheat on their production quotas, increasing supply to meet market demand and lowering their price.

- Most cartel agreements are unstable and at the slightest incentive they will quickly disband, and returning the market to competitive conditions.

The exercise of collective market power will not be stable unless sellers agree on prices and production shares; on how to divide the profits; on how to enforce the agreement; on how to deal with cheating; and on how to prevent new entry.

A cartel is in the unenviable position of having to satisfy everyone, for one dissatisfied producer can bring about the feared price competition and the disintegration of the cartel. Thus a successful cartel must follow a policy of continual compromise. Little wonder that John. S McGee wrote that:

The history of cartels is the history of double crossing.

Was it important to suck up to the Saudi dictator because of its role as swing producer in OPEC. In 1983, 1984, and 1986, for example, the Saudis produced only about 3.5 million barrels per day, despite their (then) production capacity of about 10 million barrels per day. Whatever else you can say about those production cutbacks to defend posted OPEC cartel price, they were a long time ago.

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates have large reserves relative to the financial needs of their population but what they have is only a small share of global reserves and global production of oil and trivial share if you add global shale production.

With the exception of the wake of the 1979 Iranian upheaval, and market anticipation of a possible destruction of substantial reserves in the 1990–1991 and 2003 Gulf wars, real prices of crude oil fell from 1974 through 2003. Prices increased in 2004 onwards because of demand in Asia.

Bryan Caplan summarised the views of leading oil economist James Hamilton in 2008 as follows:

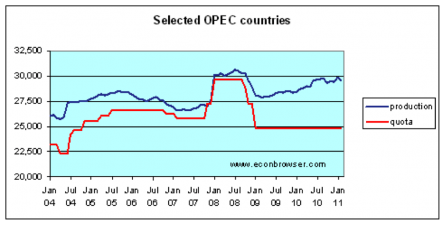

1. OPEC has almost no effect on world oil prices; most countries produce less than their quota, and when countries want to produce more, their quota goes up.

2. The price of oil follows a random walk. But the oil industry isn’t trying very hard to develop new sources because oil execs believe that the price of oil is mean-reverting (i.e., what goes up must come down). Why are the oil execs so wrong? Hamilton’s guess: They’re putting too much weight on their last big experience with high oil prices in the 70s and 80s.

No amount of cutting can support prices when supply outside OPEC is growing strongly and demand is weak in the wake of the global financial crisis and the slower recoveries both in the USA and Europe. Hamilton’s current view is that:

…of the observed 45% decline in the price of oil, 19 percentage points– more than 2/5– might be reflecting new indications of weakness in the global economy.

Whatever reason people are sucking up to the dead Saudi dictator, they have nothing to do with the global oil market.

Recent Comments