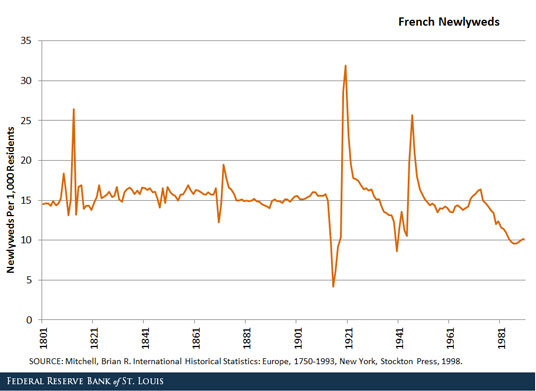

Source: How World War I Changed Marriage Patterns in Europe.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

18 May 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, economics of love and marriage Tags: dating market, economics of fertility, France, marriage and divorce, World War I

21 Apr 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of love and marriage Tags: dating markets, marriage and divorce, search and matching

29 Jan 2016 1 Comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, gender wage gap, marital division of labour, marriage and divorce

Geoff Simmons attributes part of the gender wage gap to the reluctance especially among women in high-paying jobs to haggle over pay. These women at the top end of the labour market are more likely to accept the first offer.

This relative reluctance of women to haggle over their pay is important to explaining why the gender wage gap is much larger at the top end of the labour market than at the bottom according to Geoff Simmons. Women have to haggle more if the gender pay gap is to close further.

Haggling over the wage has costs as well as benefits as Richard Epstein explained 20 years ago within a search and matching framework when commenting on a paper written by Carol Rose in 1992:

If one party is known to gobble up virtually all the cooperative surplus, then that party will find it difficult to attract deals. People anticipate getting some portion of the gain and will have a tendency to migrate to other individuals and transactions when they do not have to be ever watchful of their fair share of the gain.

If women have the characteristics that Rose attributes to them, then they would be able to enter more deals and find jobs more easily than men. At this point it becomes an empirical question: whether the greater frequency of deals (or shorter periods of unemployment) offset the tendency to gain a larger share of the profits of any given transaction.

Women will find it easier to get a job because they haggle less and therefore negotiations are less likely to breakdown, which will increase their lifetime income. This reduction in the cost of search because of a greater prospect of a match offset the losses in wages from successful haggling.

Indeed, does not this reluctance to haggle among women make it more likely that employers will hire women and promote the because their reluctance to haggle makes them cheaper. This starts off a competition between employers that will slowly drive up the wages offered to women.

It is also the case that women invest in human capital that is more mobile between the jobs and they are more likely to quit the workforce and return again after motherhood.

The ability to quickly find a job after a career interruption is a competitive advantage rather than a disadvantage.

Men have more specialised human capital and are more likely to stay in one job so they have more to gain from haggling. In comparison, women invest in human capital that is more mobile between jobs because they anticipate downscaling or quitting because of motherhood.

In such a case, it is advantageous to have human capital that appeals to a wide range of employers and become can be quickly matched so that full-time or part-time employment and the associated income stream can start quick as quickly as possible. Workers who changed jobs more often and have shorter job tenures have less to gain and more to lose from haggling and not getting the job at all.

If women do not like to haggle, does this not imply they are less likely to be attracted the jobs with performance pay? Alan Manning investigated this specific question a few years ago.

The propensity of women to seek or avoid jobs with performance pay in a more competitive workplace is an important question because up to 40% of jobs have some form of performance pay which would put women off if they do not like to haggle as Geoff Simmons implies.

Manning used jobs with performance pay in the the 1998 and 2004 British Workplace Employees Relations Survey as a proxy for the level of competition in the workplace.

If Geoff Simmons is right, women should shy away from jobs with performance pay. Women should be less likely to hold these jobs with performance pay, other things being equal. That is precisely the hypothesis that Alan Manning explored. He is a world-class labour economist. What did he find?

We find very modest evidence for differential sorting into performance pay schemes by gender, and small effects of performance pay on hourly wages. Furthermore, and unlike the laboratory studies, we find no significant effect of the gender mix in the job on the responsiveness to performance pay.

We do find some evidence for an effect of performance pay on a measure of work effort in line with the experimental evidence but the bottom line is that a very small part of the gender pay gap can be attributed to these factors.

The gender pay is already tiny in New Zealand and only a tiny part of that can be explained as any reluctance of women to compete in the workforce such as through signing on for performance pay.

Manning found that the gender mix of jobs in occupation is not affected by the presence of performance pay but it should be if women are reluctant to angle and to be competitive as suggested by Geoff Simmons.

The reluctance of women to sign on for performance pay maybe be an aspect of the asymmetric marriage premium and the marital division of effort. Mothers, unlike fathers, cannot afford to go home at the end of the workday completely exhausted if there are children to care for.

Women have a long history of carefully selecting education and other human capital and occupations to anticipate the responsibilities of motherhood and minimising human capital depreciation during the associated career interruptions. Anticipating that motherboard is a lot of work is no stretch on that occupational sorting by women.

Women still do most of the household chores? Data on who does what in the house: goo.gl/3doqy4 #statistics https://t.co/fnY0d9OgkT—

DataStories (@LindaRegber) October 24, 2015

That division of effort between the sexes has got nothing to do with the behaviour of employers and everything to do with the marital division of labour. As to what to do about that Richard Posner raised a very good conundrum in a paper from 20 years ago:

The idea the government should try to alter the decisions of married couples on how to allocate time to raising children is a strange mixture of the utopian and the repulsive. The division of labour within marriage is something to be sorted out privately rather than made a subject of public intervention.

Liberal and radical frameless can if they wanted women to stay in the labour force and have no children or fewer children, or, persuade their husbands to assume a greater role in child rearing. Others can search the contrary. The ultimate decision is best left to private choice.

I remember from decades ago a couple at work who were very modern and trying to share the child rearing equally. Their three-year-old daughter was not very cooperative because she found that her mother was much better at braiding her hair than a father. That tantrum by their three-year-old was the beginning of the end of a grand plan.

08 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of education, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - USA, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, family poverty, high school dropouts, marriage and divorce, single parents, success sequence

Source: The success sequence: Conservatives think they have a formula for raising people out of poverty.

.

22 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, economic history, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, minimum wage, occupational choice, poverty and inequality Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, Claudia Goldin, compensating differentials, economics of fertility, gender wage gap, marriage and divorce, power couples

As part of a large paper calling for massive government intervention, the Economic Policy Institute, impeccably left-wing, massed a considerable amount of evidence about the withering away of the gender wage gap and anomalies in what is left of that gap. None of these anomalies bolster the case for more regulation of the labour market.

The first of their charts showed the large reduction in the gender wage gap in the USA. Women’s wages have been increasing consistently over the last 40 years or so. The second of their tweeted charts shows that women of all races consistently outperformed men in wages growth, often by a large margin.

Their most interesting chart is about how the gender gap is not only highest among top earners, their pay gap has not fallen at all in the last 40 years. If anything, that gender wage gap is rising at the top end of the labour market albeit slowly. Progress in closing the gender gap been pretty consistent at the lower pay levels. That progress is certainly better than no progress at all.

The Economic Policy Institute didn’t enquire in any detail into why women with the most options in the labour market had made the least progress in closing the gender wage gap.

None of their solutions such as more collective-bargaining and a higher minimum wage will help the top end of the job market.

There is an anomaly in the Economic Policy Institute’s reasoning. The women who would suffer least from a purported inequality of bargaining power inherent in the capitalist system and have plenty of human capital have had least success in closing the gender pay gap. These women can shop around for better job offers and start their own businesses. Many do because they are professionals where self-employment and professional partnerships are common.

The better discussions of the gender wage gap emphasise choice. Women choosing at the top end of the labour market to balance career and family and choosing the occupation and education where the net advantages of doing that are the greatest. As the Economic Policy Institute itself notes:

In 2014, the gap was smallest at the 10th percentile, where women earned 90.9 percent of men’s wages. The minimum wage is partially responsible for this greater equality among the lowest earners, as it results in greater wage uniformity at the bottom of the distribution.

The gap is highest at the top of the distribution, with 95th percentile women earning 78.6 percent as much as their male counterparts. Economist Claudia Goldin (2014) postulates that the gap is larger for women in high-wage professions because they are penalized for not working long, inflexible hours that often come with many professional jobs, due in large part to the arrival of children and long-standing social expectations about the division of household labour between men and women.

What the Economic Policy Institute does not explain is why these long-standing social expectations about the division of household labour should be strongest among well-paid women with plenty of options.

Among these options of high-powered women in well-paid jobs is the ability to buy every labour-saving appliance, hire a nanny and ample childcare and acquire everything else on the list of demands of the Economic Policy Institute on closing the gender pay gap. Something doesn’t add up?

Of course, the Economic Policy Institute discusses the unadjusted gender wage rather than the adjusted gender wage. When you study the gender wage gap after making adjustments for demographic and other obvious factors, it is clear that this pay gap is driven by the choices women make between career and family.

Claudia Goldin did a great study of Harvard MBAs using online surveys of their careers. This is the very group that according to the Economic Policy Institute have made the least progress in bringing down patriarchy in the labour market. Specifically, the overturning of traditional expectations about the marital division of labour in childcare and parenthood.

https://twitter.com/alyssalynn7/status/669219008747610113

Goldin found that three proximate factors accounted for the large and rising gender gap in earnings among MBA graduates as their careers unfold:

The greater career discontinuity and shorter work hours for female MBAs are largely associated with motherhood. There are some careers that severely penalise any time at all out of the workforce or working less than punishingly long and rigid hours.

A 2014 Harvard Business School study found that 28 percent of recent female alumni took off more than six months to care for children; only 2 percent of men did.

Claudia Goldin found one counterfactual that cancels out the gender wage gap amongst MBA professionals: hubby earns less! Female MBAs who have a partner who earn less than them earn as much as the average MBA professional on an hourly basis but work a few less hours per week.

The gender wage gap is persisted in high-paying jobs because career women have so many options. Studies of top earning professionals show that they make quite deliberate choices between family and career. The better explanation of why so many women are in a particular occupation is job sorting: that particular job has flexible hours and the skills do not depreciate as fast for workers who take time off, working part-time or returning from time out of the workforce.

Low job turnover workers will be employed by firms that invest more in training and job specific human capital:

This is the choice hypothesis of the gender wage gap. Women choose to educate for occupations where human capital depreciates at a slower pace.

The gender wage gap for professionals can be explained by the marriage market combined with assortative mating:

This two-year age gap means that the husband has two additional years of work experience and career advancement. This is likely to translate into higher pay and more immediate promotional prospects.

An interesting and informed look at the pay gap between men and women economist.com/blogs/freeexch… https://t.co/0nxtC9ILWo—

Charles Read (@EconCharlesRead) November 06, 2015

Maximising household income would imply that the member of the household with a higher income, and greater immediate promotional prospects stay in the workforce. This is entirely consistent with the choice hypothesis and equalising differentials as the explanation for the gender wage gap. As Solomon Polachek explains:

At least in the past, getting married and having children meant one thing for men and another thing for women. Because women typically bear the brunt of child-rearing, married men with children work more over their lives than married women. This division of labour is exacerbated by the extent to which married women are, on average, younger and less educated than their husbands.

This pattern of earnings behaviour and human capital and career investment will persist until women start pairing off with men who are the same age or younger than them. That is, more women will have to start marrying down in both income and social maturity.

16 Nov 2015 1 Comment

in economics of love and marriage, labour economics, labour supply Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, British economy, male labour force participation, marriage and divorce

The number of British fathers in a couple who worked more than 45 hours a week has dropped from about 60% to under 40% since 1998.

Source: OECD Family Database.

13 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of love and marriage Tags: dating market, marriage and divorce, search and matching

“The researchers looked at different variables to understand why divorces tend to be filed by women. They suggest three main explanations:

Source: Are Women More Likely Than Men To End A Relationship? | FiveThirtyEight

01 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of love and marriage Tags: dating market, marriage and divorce, marriage market, search and matching

The linguistic features of dates that click click click click

priceonomics.com/what-people-sa… http://t.co/EhvfSjn20l—

Roseann Cima (@rosiecima) May 22, 2015

28 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of love and marriage, law and economics, occupational choice Tags: dating market, marriage and divorce, marriage market

What Professions Are Most Likely To Marry Each Other?

priceonomics.com/what-professio… http://t.co/1FVQRA67qc—

Priceonomics (@priceonomics) September 16, 2015

26 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of love and marriage, population economics Tags: economics of fertility, family demographics, marriage and divorce, search and matching

They certainly don’t go much for cohabiting in Italy or indeed the USA among young adults. Cohabitation is pretty much the same everywhere else. Marriage is not so common in Sweden generally among young people.

Source: OECD Family Database – OECD.

26 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, discrimination, economic history, economics of education, gender, growth disasters, growth miracles, human capital, labour economics Tags: College premium, compensating differentials, education premium, graduate premium, marriage and divorce, reversing gender gap

A rising majority of university students around the world are women (HT @cblatts) http://t.co/6loTmSgrk9—

William Easterly (@bill_easterly) June 15, 2015

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments