The Paid Leave Fairy Tale

05 Jun 2019 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, labour supply, law and economics, politics - USA Tags: maternity leave

Why is the Swedish gender wage gap so stubbornly stable (and high)?

06 May 2017 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: economics of fertility, female labour force participation, gender wage gap, maternity leave, preference formation, statistical discrimination, Sweden, unintended consequences

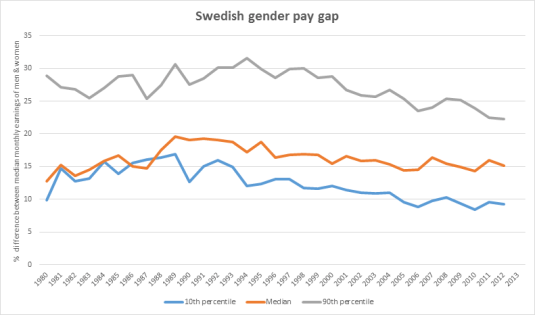

The Swedes are supposed to be in a left-wing utopia. Welfare state, ample childcare and long maternity leave but their gender wage gap is almost as bad as in 1980. They must be a misogynist throwback.

Maybe Megan McArdle can explain:

There are countries where more women work than they do here, because of all the mandated leave policies and subsidized childcare — but the U.S. puts more women into management than a place like Sweden, where women work mostly for the government, while the private sector is majority-male.

A Scandinavian acquaintance describes the Nordic policy as paying women to leave the home so they can take care of other peoples’ aged parents and children. This description is not entirely fair, but it’s not entirely unfair, either; a lot of the government jobs involve coordinating social services that women used to provide as homemakers.

The Swedes pay women not to pursue careers. The subsidies from government from mixing motherhood and work are high. Albrecht et al., (2003) hypothesized that the generous parental leave a major in the glass ceiling in Sweden based on statistical discrimination:

Employers understand that the Swedish parental leave system gives women a strong incentive to participate in the labour force but also encourages them to take long periods of parental leave and to be less flexible with respect to hours once they return to work. Extended absence and lack of flexibility are particularly costly for employers when employees hold top jobs. Employers therefore place relatively few women in fast-track career positions.

Women, even those who would otherwise be strongly career-oriented, understand that their promotion possibilities are limited by employer beliefs and respond rationally by opting for more family-friendly career paths and by fully utilizing their parental leave benefits. The equilibrium is thus one of self-confirming beliefs.

Women may “choose” family-friendly jobs, but choice reflects both preferences and constraints. Our argument is that what is different about Sweden (and the other Scandinavian countries) is the constraints that women face and that these constraints – in the form of employer expectations – are driven in part by the generosity of the parental leave system

Most countries have less generous family subsidies so Claudia Goldin’s usual explanation applies to their falling gender wage gaps

Quite simply the gap exists because hours of work in many occupations are worth more when given at particular moments and when the hours are more continuous. That is, in many occupations earnings have a nonlinear relationship with respect to hours. A flexible schedule comes at a high price, particularly in the corporate, finance and legal worlds.

Mandatory Maternity Leave is a Bad Idea @suemoroney

05 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in economics, gender, labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA Tags: maternity leave

Bridging the Gender Gap: The Problems with Parental Leave

11 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: gender wage gap, maternity leave, Parental leave

@suemoroney more generous maternity leave increases the gender wage gap @JanLogie

07 Dec 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, labour economics, labour supply, law and economics, occupational choice, politics - New Zealand Tags: do gooders, expressive voting, female labour force participation, gender wage gap, maternal labour supply, maternity leave, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

Source: Why Are Women Paid Less? – The Atlantic.

Source: AEAweb: AER (103,3) p. 251 – Female Labor Supply: Why Is the United States Falling Behind?

Maternity leave compared

30 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: gender gap, maternal labour supply, maternity leave, paternity leave

Richard Branson has announced a great paid leave policy for .2 percent of his workers

11 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, entrepreneurship, gender, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: entrepreneurial alertness, maternity leave, paternity leave, Richard Branson

The NYT must be slipping with "When Family-Friendly Policies Backfire”

27 May 2015 2 Comments

in discrimination, economics of regulation, gender, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: gender wage gap, maternity leave, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

The best part of the article is its frank admission about how bare the cupboard is in dealing with the impact of generous maternity leave on the gender gap. Maternity leave should not be too generous, should not be paid by employers but by taxpayers, and should extend to both men and women.

Why is the gender gap so large and the glass ceiling so thick in Sweden?

14 May 2015 1 Comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, human capital, labour economics, occupational choice, politics - USA Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, do gooders, economics of families, gender wage gap, maternity leave, Sweden, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

The gender wage gap is no better than the OECD average, despite generous maternity and paternity leave. What gives?

America: one day a year celebrating mothers, fathers.

Sweden: 480 days paid leave per child. vox.com/2014/5/12/5708… http://t.co/weFDrTj7Jb—

Ezra Klein (@ezraklein) May 11, 2015

Source: Closing the gender gap: Act now – http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264179370-en

How big is the wage gap in your country? bit.ly/18o8icV #IWD2015 http://t.co/XTdntCRfDQ—

(@OECD) March 08, 2015

One important question is whether government policies are effective in reducing the gap. One such policy is family leave legislation designed to subsidize parents to stay home with new-born or newly adopted children.

One of the RLE articles shows that for high earners in Sweden there is a large difference between the wages earned by men and women (the so-called “glass ceiling”), which is present even before the first child is born. It increases after having children, even more so if parental leave taking is spread out.

These findings suggest that the availability of very long parental leave in Sweden may be responsible for the glass ceiling because of lower levels of human capital investment among women and employers’ responses by placing relatively few women in fast-track career positions. Thus, while this policy makes holding a job easier and more family-friendly, it may not be as effective as some might think in eradicating the gender gap.

via New volume on gender convergence in the labour market | IZA Newsroom.

Longer Maternity Leave Not So Great for Women After All

01 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in economics Tags: gender wage gap, maternity leave, unintended consequence

The left-wing parties around the world and in New Zealand have long tried to keep women’s wages down and hold their careers back by increasing the generosity of maternity leave.

Francine Blau argues that:

- Family-friendly policies make it easier for women to combine work and family and women’s advancement at work. Such policies facilitate the labor force entry of less career-oriented women (or of women who are at a stage in the life cycle when they would prefer to reduce labor market commitments).

- Long, paid parental leaves and part-time work may encourage women who would have otherwise had a stronger labor force commitment to take part-time jobs or lower-level

positions. - Such policies may lead employers to engage in statistical discrimination against women for jobs leading to higher-level positions, if employers cannot tell which women are likely to avail themselves of these options and which are not. These policies may leave women less likely to be considered for high-level positions.

More women will work more women will work as a result of maternity leave, but more of these women all work part time, instead of full-time.

At bottom, paying women to spend extended periods of time out of the workforce at crucial times of their career in their late 20s and their 30s does them no favours in terms of advancing their careers.

Recent Comments