Height differences of couples. #dating #dataviz

Source: fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/how-co… http://t.co/gXsS16uER6—

Randy Olson (@randal_olson) December 05, 2014

Height differences of couples

05 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of love and marriage, law and economics Tags: marriage and divorce, search and matching

Every 20 years we worry about losing jobs to technology

26 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, technological progress Tags: creative destruction, search and matching, technological unemployment

Every generation has its moral panic about technological change in creative destruction.

For young people, it’s that overweening conceit about the problems they are attempting to solve are new.

For the middle-aged and older, rather than suggest that they are policy hustlers, it’s more like you they simply forgot that these debates were had 20 years ago and the scaremongers lost the same reason they lost 20 years before that, and so on.

HT: https://twitter.com/JamesBessen/status/498435714322014208

The marvel of the market: the remarkable foresight of young adults in choosing what to study

16 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in Alfred Marshall, Armen Alchian, economics of education, George Stigler, human capital, job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice, politics - New Zealand, rentseeking Tags: 2nd laws of supply and demand, Alfred Marshall, Armen Alchian, george stigler, search and matching, skills shortgaes

Known but yet to be exploited opportunities for profit do not last long in competitive markets, including hitherto unnoticed opportunities for the greater utilisation and development of skills and experience (Hakes and Sauer 2006, 2007; Ryoo and Rosen 2004; and Kirzner 1992). Moneyball is the classic example of entrepreneurial alertness to hitherto unexploited job skills which were quickly adopted by competing firms (Hakes and Sauer 2006, 2007).

There is considerable evidence that the demand and supply of human capital responds to wage changes. For example, over- or under-supplied human capital moves either in or out in response to changes in wages until the returns from education and training even out with time (Ryoo and Rosen 2004; Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang 2012; Ehrenberg 2004).

As evidence of this equalisation of returns on human capital investments across labour markets, the returns to post-school investments in human capital are similar – 9 to 10 percent – across alternative occupations, and in occupations requiring low and high levels of training, low and high aptitude and for workers with more and less education (Freeman and Hirsch 2001, 2008). There is evidence that workers with similar skills in similarly attractive jobs, occupation and locations earn similar pay (Hirsch 2008; Vermeulen and Ommeren 2009; Rupert and Wasmer 2012; Roback 1982, 1988).

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) found that the labour supply and university enrolment decisions of engineers is “remarkably sensitive” to career earnings prospects. Graduates are the main source of new engineers. Engineers who moved out into other occupations such as management did not often moved back to work again as professional engineers. Ryoo and Rosen (2004) observed when summarising their work that:

Both the wage elasticity of demand for engineers and the elasticity of supply of engineering students to economic prospects are large. The concordance of entry into engineering schools with relative lifetime earnings in the profession is astonishing.

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) found several periods of surplus in the market for engineers. These periods of shortage or surplus corresponded to unexpected demand shocks in the market for engineers such as the end of the Cold War.

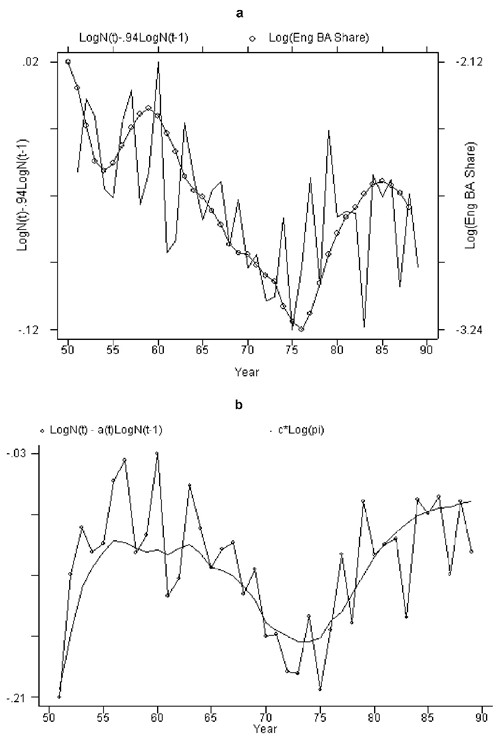

Figure 1: New entry flow of engineers: a, actual vs. imputed from changes in stock of engineers; b, time-varying coefficients.

Source: Ryoo and Rosen (2004)

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) noted that importance of permanent versus transitory changes in earnings. Transitory rises and falls in earnings prospects have much less influence on occupational choices and the educational investments of students.

In light of these findings that the supply of engineers rapidly adapted to changing market conditions, Ryoo and Rosen (2004) questioned whether public policy makers have better information on future labour market conditions than labour market participants do. When politicians get worked up about skill shortages, the markets for scientists and engineers often where they make extravagant claims about the ability of the market to adapt to changing conditions because of the long training pipeline involved in university study, including at the graduate level.

There can be unexpected shifts in the supply or demand for particular skills, training or qualifications. These imbalances even themselves out once people have time to learn, update their expectations and adapt to the new market conditions (Rosen 1992; Ryoo and Rosen 2004; Bettinger 2010; Zafar 2011; Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang 2012; Webbink and Hartog 2004).

For example, Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang (2012) found that both expected earnings and students’ abilities in the different majors are important determinants of student’s choice of a college major, and 7.5% of students would switch majors if they made no forecast errors.

The wage premium for a tertiary degree was low and stable in New Zealand in the 1990s (Hylsop and Maré 2009) and 2000s (OECD 2013). This stability in the returns to education suggests that supply has tended to kept up with the demand for skills at least over the longer term at the national level. There were no spikes and crafts that would be the evidence of a lack of foresight among teenagers in choosing what to study.

All in all, the remarkable sensitivity of engineers to a career earnings prospects, the frequent changes of college majors by university students in response to changing economic opportunities, and the stability of the returns on human capital over time suggest that the market for human capital is well functioning.

The argument that the market was not working well was assumed rather than proven. Likewise, the case for additional subsidies for science, technology, engineering and mathematics because of perceived skill shortages has not been made out. There is a large literature showing that the market for professional education works well.

The onus is on those who advocate intervention to come up with hard evidence, rather than innate pessimism about markets that are poorly understood because of a lack of attempts to understand it. Studies dating back to the 1950s by George Stigler and by Armen Alchian found that the market for scientists and engineers works well and the evidence of shortages were more presumed than real.

For those who are job-hunting after the holidays

12 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in job search and matching, personnel economics Tags: search and matching

I find the biggest mistake made at job interviews at the interview panel forget that you are interviewing them as prospective employer.

If they can’t even be polite and friendly to you before you work for them, imagine what they’re like every day.

About 20% of the people I’ve met at job interviews I would never want to work with, much less work for.

Was Moynihan, right? The role of prospective success in assortative mating in family poverty

19 Dec 2014 1 Comment

Armen Alchian on the inconsistent treatment of the concept of cost in economic theory

17 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

WH Hutt on job search

14 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in job search and matching, labour economics, macroeconomics, unemployment Tags: job search, search and matching, unemployment, voluntary unemployment

Unemployment, job search, search and matching

Unemployment, job search, search and matching

Second law of supply and demand alert: There is no such thing as a skills shortage – updated

01 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, unemployment Tags: Alfred Marshall, Armen Alchian, comparative statics, labour market shortages, search and matching, second law of demand, second law of supply, skill shortages, unemployment

Could you define both a severe skills shortage and a skills shortage?

- How do these concepts differ from concepts such as rising demand, rapidly rising demand, and reduced and sharply reduced supply?

- Are the phrases severe skills shortage and a skills shortage more precise than the phrases rising demand, rapidly rising demand, and reduced and sharply reduced supply?

- Are the phrases severe skill shortage and a skill shortage more informative than referring to the short and long run elasticity of demand and supply as summed up in the second laws of demand and supply?

- Why are rising demand, rapidly rising demand, and reduced and sharply reduced supply considered to be social problems. What causes rising demand, rapidly rising demand, and reduced and sharply reduced supply?

- For whom are rising demand, rapidly rising demand, and reduced and sharply reduced supply considered to be problems? Employers? Employees? Others?

- Should governments intervene to stop employers from competing to set wages to reflect increases in the marginal revenue product of labour?

- Is not the purpose of short and long-term upward changes in relative prices or wages to induce people to buy less of a now scarcer resource and search for substitutes and additional sources of supply, and for new suppliers to enter the market in response to the higher prices or wages?

As a starter, I thought I would update Alchian and Arrow’s timeless 1958 analysis for the Rand Corporation of the purported shortage of engineers and scientists at the height of the missile gap in the cold war.

Alchian and Arrow tested the robustness of claims of a labour market shortage of scientists and engineers by investigating the sudden appearance of a servant shortage during World War II.

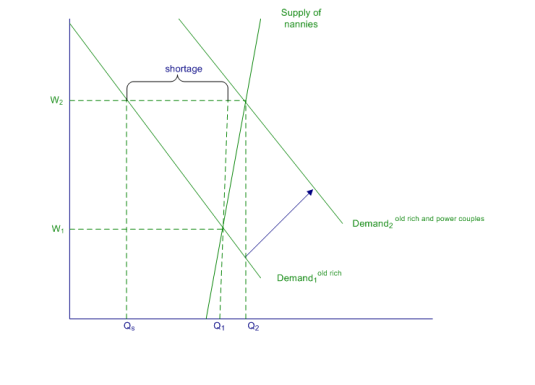

I will update this idea of a servant shortage to a purported shortage of nannies, as shown in figure 1 below which sets out the initial equilibrium and then an increase in demand.

Figure 1: the demand and supply for nannies by the old rich and power couples

In the diagram above, the initial equilibrium has the old rich hiring Q1 nannies at a wage W1 with demand curve D1, and the supply curve for nannies.

- Power couples then enter the nannies market pushing total demand out to D2 with wages increasing to W2 and quantity supplied increasing a little to Q2;

- The old rich can now afforded to buy only Qs in nannies and power couples hire (Q2 – Qs) in nannies.

By construction, the quantity of nannies supplied increases slightly in the short-run, with a large increase in wages for nannies! (Q2 – Q1) new nannies enter the market, lured in by the higher wages.

The old rich now face a shortage of nannies equal to the quantity (Q1 – Qs). These nannies having switched to work for power couples on much better pay. (In the case of the original analysis Alchian and Arrow analysis, they switched into defence work or backfilled jobs of those that moved into defence work).

As with the wartime servant shortage, the old rich are unwilling to admit they are no longer able to keep themselves in the style they were accustomed too because the demand for domestic labour has increased.

Better to blame their loss of social status on a skills shortage in a poorly functioning market rather than accept the rise of middle class power couples outbidding them in the hire of domestic help. As Alchian and Arrow (1958, pp. 39-40) explain:

… Many people who formerly consumed some of the commodity or service in question and now find the price so high that they no longer want as much (or any) would describe the situation is one of “shortage”.

Actually, this is merely one way of saying that they can’t get the given commodity at its old price.

We can think of many examples of this use of the word “shortage”. For example, the “servant shortage” during World War II was a case in point.

Those with whom the increase in household servants wages were more than they could afford to pay, apparently found it more convenient to describe their change in circumstances as a result of a “shortage” than to admit baldly that they couldn’t afford to keep the servants…

It seems reasonable to explain a good deal of the current complaint about a shortage of scientists and engineers is a variant of the “servant shortage” phenomena.

Employers who find themselves losing engineers to other firms and at the same time find it uneconomic to try and keep these employees by offering them substantial salary increases may see the situation as a “shortage” rather than recognise that other firms can put these skills to more valuable uses…

While we lack specific evidence, we have the impression that the firms who have complained most consistently about “shortage” have been those whose demand has not increased or at least not increased as rapidly as that of other firms in their industry.

Why are people priced out of any market? Given a fixed income and the many other alternative uses of their incomes, any rise in price makes buying the old quantity no longer the best bargain.

Who will admit that they can no longer keep themselves in the style they were accustomed to when they complain of market failure, skill shortages and lack of government investment in skill formation.

Alfred Marshall’s comparative statics of price adjustment

The analysis of the time path of price adjustment for any commodity was developed by Alfred Marshall in 1890. He was concerned that time was an important factor in how the markets adjusted to demand and supply changes:

… markets vary with regard to the period of time which is allowed to the forces of demand and supply to bring themselves into equilibrium with one another, as well as with regard to the area over which they extend. And this element of Time requires more careful attention just now than does that of Space.

For the nature of the equilibrium itself, and that of the causes by which it is determined, depend on the length of the period over which the market is taken to extend.

We shall find that if the period is short, the supply is limited to the stores which happen to be at hand: if the period is longer, the supply will be influenced, more or less, by the cost of producing the commodity in question; and if the period is very long, this cost will in its turn be influenced, more or less, by the cost of producing the labour and the material things required for producing the commodity.

Marshall divided the price adjustment process into the market period, the short run, and the long run.

In the market period, production is fixed; and all factors of production are fixed in supply during this time period. The burden of price adjustment is on the demand side.

As the supply is fixed in the market period, it is shown as a vertical line SMP. It is also called as inelastic supply curve. When demand increases from DD to D1 D1, price increases from P to P1. Similarly, a fall in demand from DD to D2 D2 pull the price down from P to P2.

In the short run, supply to be partially adaptable, in the sense that increased production can occur but capital equipment and certain other overhead items are held constant.

SSP is elastic implying that supply can be increased by changing a variable input. Note that the corresponding increase in price from P to P1 for a given increase in demand from D to D1 is less than in the market period. It is because the increase in demand is partially met by the increase in supply from q to q1.

The short run is the conceptual time period in which at least one factor of production is fixed in amount and others are variable in amount. In the short run, a profit-maximising firm will:

- increase production if marginal cost is less than marginal revenue;

- decrease production if marginal cost is greater than marginal revenue;

- continue producing if average variable cost is less than price per unit, even if average total cost is greater than price;

- Shut-down if average variable cost is greater than price at each level of output.

In the long run, supply is fully flexible – there are no fixed factors of production. The Marshallian long-run allows for optimal capital stock adjustment.

The long period supply curve SLP is more elastic and flatter than that of the SSP. This implies the greater extent of flexibility of the firms to change the supply.

The price increases from P to P2 in response to an increase in demand from D to D1 and it is less than that of the market period (P1) and short period (P2). It is because the increase in demand is fully met by the required increase in supply. Hence, supply plays a significant role in determining the lower equilibrium price in the long run.

The market is cleared in the long run within a framework in which supply can be considered to be fully adaptable because all factors have adjusted to the new situation. Alfred Marshall explains:

In long periods on the other hand all investments of capital and effort in providing the material plant and the organization of a business, and in acquiring trade knowledge and specialized ability, have time to be adjusted to the incomes which are expected to be earned by them: and the estimates of those incomes therefore directly govern supply, and are the true long-period normal supply price of the commodities produced.

In addition, in the market period, the short run, and the long run, foresight is not perfect, information is not free, and the cost of adjusting something is not independent of the speed in which you wish to do so.

The 2nd laws of supply and of demand

Another way to discuss how time interacts with responsiveness of supply and demand are the second laws of supply and demand.

The Second Law of Supply states that supply is more responsive to price in the long run. The Second Law of Supply relates to how flexible producers are in terms of how much of a good they produce.

Supply is more elastic in the long run because given more time, producers can more easily adapt to the change in the price.

Within shorter periods of time, producers cannot as easily change the amount of a good they produce (since changes in production often require adjustments within factories, with workers etc.)

The Second Law of Demand states that demand is more responsive to price in the long run than in the short run. Initially, when the price of a good increases or decreases, consumption does not change drastically. However, when consumers are given more time to react to the change in price, consumption can either increase or decrease more dramatically. Demand is not only determined by price but also factors such as: income, tastes, and the price of related goods.

In the market period, any adjustment must be made through changes in price. This means that there could be initially a large price increase.

In the short run, there are some capability for more supply to come forward. This additional supply will temper the initial large price increase.

In the long run, producers are fully able to adapt their circumstances to the changing market conditions and higher prices. This will reduce prices as compared to the initial price spike when market conditions first changed.

In the long run, new firms can enter the industry and old firms can exit as required by the price change and their entrepreneurial expectations of the future of the industry.

Search and matching in a decentralised labour market

To cover off the bases, the simultaneous existence of vacancies and unemployed in a labour market is no evidence of either of surplus or shortage. It takes time for workers to locate vacancies and assess their competing job options. It takes time for employers to locate suitable workers to fill vacancies.

The simultaneous existence of vacancies and unemployed is the result of, as mentioned earlier, imperfect foresight, the fact that information is not free, nor freely available, and the costs of doing anything is not independent of the speed in which you wish to act. Searching for suitable vacancies, or suitable employees, is costly, and neither jobseeker nor employer knows whether any match will work out.

The one-price (one-wage) market that clears instantly will occur only where the cost of information about the prices (wages) offered by buyers and sellers is zero. As George Stigler observed in the opening paragraph of his famous 1961 paper The Economics of Information:

One should hardly have to tell academicians that information is a valuable resource: knowledge is power. And yet it occupies a slum dwelling in the town of economics.

Mostly it is ignored: the best technology is assumed to be known, the relationship of commodities to consumer preferences is a datum.

And one of the information producing industries, advertising, is treated with a hostility that economists normally reserve for tariffs or monopolists.

Job search cost are of two types: direct costs of gathering information about competing opportunities and the opportunity cost of being unemployed or staying in your current job at your current pay.

- The benefit from job search is the expected gain in earnings that will result from waiting for a better wage offer.

- The rational job searcher searches for better offers until the marginal benefit and cost of additional search are equal.

- A significant cost of continued job search is the earnings foregone by not taking the previous best opportunity.

Unemployment can be a cost-effective method of searching for better employment opportunities and higher wage offers as David Andolfatto observed:

One frequently reads that “unemployment represents wasted resources.”

But if job search is an information-gathering activity, designed to locate a high quality job match, in what sense does such an activity necessarily constitute wasted resources? (Does the existence of single people in the marriage market also represent wasted resources?)

If the unemployment rate were to suddenly plummet because a large number of workers aborted their job search activity–accepting crappy jobs, or exiting the labour force–is this a reason to celebrate?

The behavioural responses of employers and workers to change are so pronounced because the cost of acquiring new information is profound (Alchian 1969). Many such costs impede wages from instantly fluctuating to rebalance labour supply with demand. Hicks (1932) explained this uncertainty and state of flux as follows:

For although the industry as a whole is stationary, some firms in it will be closing down or contracting their sphere of operations, others will be arising or expanding to take their place.

Some firms then will be dismissing, others taking on, labour; and when they are not situated close together, so that knowledge of opportunities is imperfect, and transference is attended by all the difficulties of finding housing accommodation, and the uprooting and transplanting of social ties, it is not surprising that an interval of time elapses between dismissal and re-engagement, during which the workman is unemployed.

A job seeker does not initially know the location of suitable vacancies, the wages for various skills, differences in job security and other factors. Job seekers must search for this information, keep this knowledge current and forecast whether better vacancies may open soon. Employers must search to learn the location, availability and asking wages of applicants. There is a tendency for unpredicted wage changes to induce costly additional job search. Long-term contracts arise to share risks and curb opportunism over sunken investments in relationship-specific human and organisation capital. These factors all lead to queues, unemployment, spare capacity, layoffs, shortages, inventories and non-price rationing in conjunction with wage stability (Alchian 1969; Alchian and Allen 1967, 1973; Klein 1984; Hashimoto and Yu 1980; Hall and Lazear 1979).

By acquiring more information, a job seeker learns more about their options and can improve their prospects of finding better-paid job matches. Job seekers and employers invest time and resources to find one another, size each other up and form a job match or try their luck elsewhere. A job match is a pairing of a worker with a particular employer.

Job seekers will apply for a portfolio of job vacancies that reflect their asking wage and their known alternatives. An asking wage is the minimum that a job seeker is willing to accept given their options.

- The extent of job search depends on the costs of job-information production and acquisition, the income available to job seekers while searching, the frequency and the magnitude of shifts in the relative demand between different sectors, the costs of relocation and retraining, and the extent and frequency of declines in aggregate demand (Alchian and Allen 1967).

- The more varied will be the potential job opportunities and the greater will be the gains to job seekers from continued job search, the greater are the rate of change in tastes and demand, the greater are the differences in the skills of job seekers and the requirements of job vacancies, and the greater are the costs of moving (Alchian and Allen 1967).

Employers face an information dilemma as well. If they wait a bit longer, hold a job vacancy open, a better job applicant may come a long and a more profitable and longer lasting job match may result.

Of course, the employer is taking a chance here on the job applicant pool improving with time. There are elements of luck involved for both employers and job seekers when filling vacancies and finding jobs.

The employer must balance the costs of holding the vacancy open with his estimation of the value and probability of a better applicant applying at a later date if he searches further the prospective recruits. But reducing your ignorance has costs as Stigler (1961) explained:

Ignorance is like sub-zero weather: by a significant expenditure its effects upon people can be kept within tolerable or even comfortable bounds, but it would be wholly uneconomical entirely to eliminate all its effects.

The rate at which job vacancies are filled and the rate at which people leave unemployment and change jobs is determined by the job search decisions of job seekers and the recruitment decisions of employers. The way in which the process works is well explained by Andolfatto’s analogy to the marriage market:

In many ways, the labour market resembles a matching market for couples.

That is, one is generally aware that the opposite side of the market consists of better and worse matches (we seldom take the view that there are no potential matches).

The exact location of the better matches is unknown, but may be discovered with some effort.

In the meantime, it may make sense to refrain from matching with ‘substandard’ opportunities that are currently available.

But since search is costly, it will generally not be optimal to wait for ones “soul mate” to come along. Furthermore, since relationships are not perfectly durable, there is no reason to expect the stock of singles to converge to zero over time

As in the labour market, there are marriages and divorces and young people come of age and look for the first time; people also link up for short-term relationships; and some relationships do better than others.

To say there is involuntary unemployment is to say there is also involuntarily unmarried people. But we can always marry the first person we meet in the street, if they’ll have us. Search and matching is a two sided affair. I doubt that our first encounter in the street would accept this offer of marriage from a stranger. I doubt that anyone would want to marry a stranger who would so willingly marry a stranger. I think both sides suspect that such a random pairing would not last long because the pairing occurred after so little mutual scrutiny and measured assessment of alternatives, current and prospective. The same principles apply to search and matching in the labour market.

Armen Alchian on the difference between market equilibrium and market clearing

28 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

A response to Judith Sloan on monopsony

11 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in economics, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: Alan Manning, minimum wage, monopsony, search and matching

In the monopsony view view, search frictions in the labour market generate upward sloping labour supply curves to individual firms even when firms are small relative to the labour market.

Peter Kuhn in a great review of monopsony in motion pointed out the correct title was search fictions with wage posting and random matching in motion.This precision is important because, as Kuhn goes on to say:

“Manning clearly recognizes this weakness of search-based monopsony models, and does his best to address it in his discussion of ‘random’ vs. ‘balanced’ matching on pages 284–96. Manning’s basic general-equilibrium monopsony model, set out in chapter 2, assumes ‘random matching’, which means that, regardless of its size, every firm—from the local bakery to Microsoft—receives the same absolute number of job applications per period. The only way for a firm to expand its scale of operations in this model is to offer a higher wage… it is absolutely critical to the search-based monopsony model at the core of this book that there be diminishing returns to scale in the technology for recruiting new workers. In other words, for the theory to apply, firms must find it harder to recruit a single new worker the larger the absolute number of workers they currently employ.”

The evidence in favour of the monopoly view of minimum wage is is not as good as people think.

Under this monopsony view of minimum wages – an upward sloping supply curve of labour – an increase in the minimum wage increases both wages and employment.

That is, there is a very specific joint hypothesis of both more employment and more wages and as there are more workers in the workplace, higher output which the employer can only sell by cutting their prices.

David Henderson made very good points along this line when he reviewed David Card’s book back in 1994:

Interestingly, Card’s and Krueger’s own data on price contradict one of the implications of monopsony. If monopsony is present, a minimum wage can increase employment. These added employees produce more output. For a given demand, therefore, a minimum wage should reduce the price of the output. But Card and Krueger find the opposite. They write: ‘[P]retax prices rose 4 percent faster as a result of the minimum-wage increase in New Jersey…’ (p. 54). If their data on price are to be believed, they have presented evidenceagainst the existence of monopsony. David R. Henderson, “Rush to Judgment,”MANAGERIAL AND DECISION ECONOMICS, VOL. 17, 339-344 (1996)

Job finding rates under work for the dole when there is involuntary unemployment

03 Aug 2014 6 Comments

in business cycles, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, welfare reform Tags: Active labour market programs, Jeff Borland, mandatory work requirements, search and matching, welfare reform, work for the dole

Jeff Borland is a critic of work for the dole. He points out that they do not improve the job finding rates of participants and in fact reduce the amount of job search because work for the Dole participants are busy undertaking work for the dole requirements:

The main reason is that participation in the program diverts participants from job seeking activity towards Work for the Dole activity. Research on similar programs internationally has come up with comparable findings.

This made me wonder. If unemployment is caused by deficient aggregate demand, and otherwise is involuntary, how can work for the dole increase unemployment or reduce the rate at which people exit unemployment?

‘Involuntary’ unemployment occurs when all those willing and able to work at the given real wage but no job is available, i.e. the economy is below full employment. A worker is ‘involuntary’ unemployment if he or she would accept a job at the given real wage. Keynesians believe money wages are slow to adjust (e.g. due to money illusion, fixed contracts or because employers and employees want long run money wage stability), and so the real wage may no adjust to clear the labour market: there can be ‘involuntary’ unemployment.

Under the deficient aggregate demand theory of unemployment, people have no control over why they are unemployed – that’s why their unemployment is involuntary.

Sticky wages are no less sticky when work for the dole is introduced and people search more intensively for jobs. Deficient demand unemployment is no less deficient when there is an increase in job search intensity.

Work for the dole must be carefully defined, of course, to differentiate it from the failed active labour market programs of the past that attempted to improve the employability of the unemployed. By work for the dole, I simply mean mandatory work requirements simply make it more of an ordeal to be on unemployment and thereby encourage people to find a job.

Mandatory work requirements simply tax leisure. By taxing leisure, mandatory work requirements change the work leisure trade-off between unemployment and seeking a job with greater zeal and a lower asking wage more attractive option. More applicants asking for lower wages will mean employers can fill jobs faster and at lower wages, which means our create more jobs in the first place.

The probability of finding a job for an unemployed worker depends on how hard this individual searches and how many jobs are available: Chance of Finding Job = Search Effort x Job Availability

Both the search effort of the unemployed and job creation decisions by employers are potentially affected by unemployment benefit generosity and mandatory work for welfare benefits requirements.

Modern theory of the labour market, based on Mortensen and Pissarides provides that more generous unemployment benefits put upward pressure on wages the unemployed seek. If wages go up, holding worker productivity constant, the amount left to cover the cost of job creation by firms declines, leading to a decline in job creation.

Everything else equal under the labour macroeconomics workhorse search and matching model of the labour market, reducing the rewards of being unemployed exerts downward pressure on the equilibrium wage. This fall in asking wages increases the profits employers receive from filled jobs, leading to more vacancy creation. More vacancies imply a higher finding rate for workers, which leads to less unemployment. The vacancy creation decision is based on comparing the cost of creating a job to the profits the firm expects to obtain from hiring the worker.

When unemployment benefits are less generous or more onerous work requirements are attached, some of the unemployed will become less choosey about the jobs they seek in the wages they will accept. a number of people at the margin between working or not. An example is commuting distance to jobs. A number of people turn down a job because is just that little too far to commute. A small change in the cost of accepting that job would have resulted in them moving from being unemployed to fully employed.

Unemployment is easy to explain in modern labour macroeconomics: it takes time for a job seeker to find a suitable job with a firm that wishes to hire him or her; it takes time for a firm to fill a vacancy. Search is required on both sides of the labour market – there are always would-be workers searching for jobs, and firms searching for workers to fill vacancies.

In a recession, a large number of jobs are destroyed at the same time. It takes time for these unemployed workers to be reallocated new jobs. It takes time for firms to find where it is profitable to create new jobs and find workers suitable to fill these new jobs.

Recessions are reorganisations. Unemployed workers look for jobs, and firms open vacancies to maximize their profits. Matching unemployed workers with new firms firms is a time-consuming and costly process.

Will work-for-the-dole work in Australia?

29 Jul 2014 12 Comments

in labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, unemployment, welfare reform Tags: benefit exhaustion spike, search and matching, unemployment insurance, US welfare reforms, welfare reform

One of the strongest empirical findings of modern labour economics is the benefit exhaustion spike. This is the large increase, shown in the diagram, in the probability of finding a job on the eve of exhausting unemployment benefits or unemployment insurance eligibility.

This benefit exhaustion spike is mobile: when unemployment insurance eligibility is lengthened, the benefit exhaustion spike moves out to the new benefit exhaustion date. For example, from 26 weeks, then to 39 weeks, then 52 weeks and then to 99 weeks. There is also a benefit exhaustion spike where the generosity of unemployment or other insurance decreases after a certain time. The alleged decay in the human capital of the long-term unemployed does not seem to affect this benefit exhaustion spike.

In addition, in the EU, the job finding probability of unemployment insurance recipients eligible for other welfare schemes are less sensitive to changes in the level and duration of their unemployment benefits benefits.

The benefit exhaustion spike shows that job seekers have much more control over their re-employment prospects than is commonly granted even in the worst of economic conditions such as in Pittsburgh in the early 1980s in a major recession and when US manufacturing industry industry was in a long-term decline.

The individual’s reservation wage (i.e. the lowest wage wage at which individuals will accept a job offer) decreases whilst search intensity increases as they approach unemployment benefit eligibility exhaustion.

This reduction in reservation wages or the asking wages of job seekers increases the incentives for employers to post new vacancies because they can fill them at a lower cost. Both more intensive job search and more vacancies will see jobs filled faster, and more jobs created and filled.

A mechanism for reducing welfare programme entry rate while increasing welfare benefit exits is mandatory minimum job search and mandatory work requirements such as those proposed this week for Australia. These minimum hours can be spent working part time, in study and training, work preparation and job search assistance or volunteering. A work requirement is a screening device that removes any advantage of moving on to welfare in terms of more leisure time.

The proposals announced this week in Australia are most job seekers will be required to look for up to 40 jobs per month and work for the dole will be mandatory for all jobseekers younger than 50. Job seekers younger than 30 would have to work 25 hours a week under the expanded programme, while those between 30 and 49 will be asked to do 15 hours work a week, and those aged 50-60, 15 hours a week.

At least 13 OECD member countries require at least monthly visits to a local employment office by unemployment beneficiaries to present job-search evidence and also perhaps to receive advice and even referrals to specific job openings.

Reforms in a range of overseas countries that introduced more intensive monitoring of job search and stronger sanctions on benefits for non-compliance significantly reduced unemployment spells.

One of the surprising results of more intensive monitoring of job search and a requirement to sign on regularly at the local employment office or Social Security office is the sheer horror of having to sign-on and talk to caseworker for five minutes encourages 5 to 10% of unemployed beneficiaries to find a job. When unemployment and sickness beneficiaries are required to undergo a full reassessment of their eligibility, it is common for up to 30% of them simply to not reapply.

The stronger monitoring of job search and the real prospect of stiffer sanctions for non-compliance encourages all benefit claimants, current and future, and not just those actually sanctioned to search harder for jobs. This anticipation of stricter monitoring and more frequent eligibility reviews has a much larger effect of welfare dependency than the actual sanctioning of the non-complaint. People review their options and marshalled their resources to find or stay in work.

The welfare exit effect and welfare entry deterrence arises from mandatory work requirements from the relative non-financial rewards of working and not working having changed in favour of staying in full-time and semi-work for persistent workers temporarily on a welfare benefit.

Persistent workers gain from anticipating the onerous nature of work requirements and searching more intensively for jobs which are more stable and enduring. These job seekers may reduce their asking wage to win a lower paid but steadier job.

Seasonal and temporary jobs will be less attractive if there are work requirements. The incentive to cycle between the benefit and part-time and full-time work including seasonal and temporary jobs are reduce because work requirements make welfare receipt more onerous. Those job seekers with fewer outside of the workforce obligations such as young children are the most likely to move to (stable) full-time work because of work requirements.

A work requirement as a condition for a welfare benefit receive unambiguously increases net labour supply and reduces the number of people relying on the welfare system now and into the future.

The number of people working increase and some leave welfare rather than comply with the mandatory work programmes. Work requirements make welfare receipt unambiguously less attractive and will close the gap between earning full-time wages and the net rewards of not working or part-time work and partial benefit receipt.

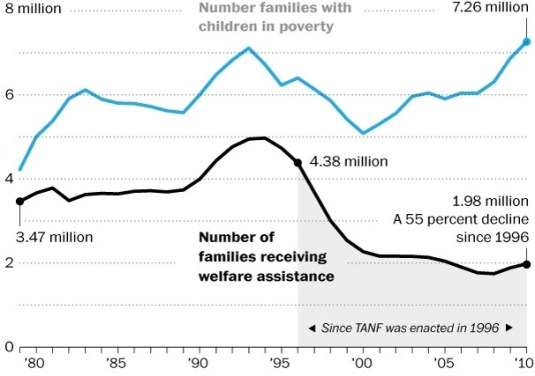

There was a more than 60% reduction in welfare caseloads after the 1996 federal welfare reform in the USA that introduced work requirement and five year lifetime federal welfare eligibility time limits on a national basis. In the four decades preceding the 1996 welfare reform, the number of Americans on welfare had never significantly decreased.

The gains in U.S. employment after the 1996 Federal welfare reform were largest among the single mothers previously thought to be most disadvantaged: young (ages 18-29), mothers with children aged under seven, high school drop-outs, and black and Hispanic mothers. These low-skilled single mothers in the USA were thought to face the greatest barriers to employment.

The U.S. literature has many competing estimates of the relative effects of work requirements, lifetime time limits and a far more generous earned income tax credit (EITC). It is agreed that work requirements and time limits reduced entry into welfare caseloads. The relative importance of time limits, work mandates and greater EITC generosity for exits is more disputed.

The Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP) had a more complex experimental design that allowed separate evaluation of the mandatory welfare-to-work program and the lower benefit reduction rate. The results indicated that the lower benefit abatement rates appear to have had little labour supply effect. The increase in labour supply seems to have come almost entirely from the mandatory welfare-to-work program and its associated sanctions.

Much was initially made in the US empirical literature of the strong state of the American economy in the 1990s as an explanation for part of the drop in welfare caseloads. The relevance of this faded when welfare caseloads did not increase again when the economy deteriorated after 2007 in the USA.

Recent Comments