M.A. Adelman on the use of knowledge and resource exploration and conservation

08 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

M.A. Adelman on the use of knowledge in resource exploration and conservation

29 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

Housing habitability laws

25 Nov 2014 1 Comment

in economics of regulation, urban economics Tags: consumer products standards, do gooders, economics of regulation, nanny state, offsetting behaviour, rent control, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, urban economics

Minimum standards for rental housing is back in the news in New Zealand. After some deaths in some rather nasty fires in rental houses without fire alarms, there are demands that landlords must put fire alarms in place and maintain those fire alarms. About a dozen people or so die in fires in New Zealand every year.

The fact that in the proposed regulation, landlords are also required to maintain those fire alarms – ensure they have batteries in them – is a microcosm of the economics of rental housing habitability laws.

Even when landlords put in fire alarms, low income tenants prefer to spend their money on something other than replacement batteries for those alarms. These tenants are presumed to be competent to vote and drive cars, but not manage the risk of fires in the houses in which they live.

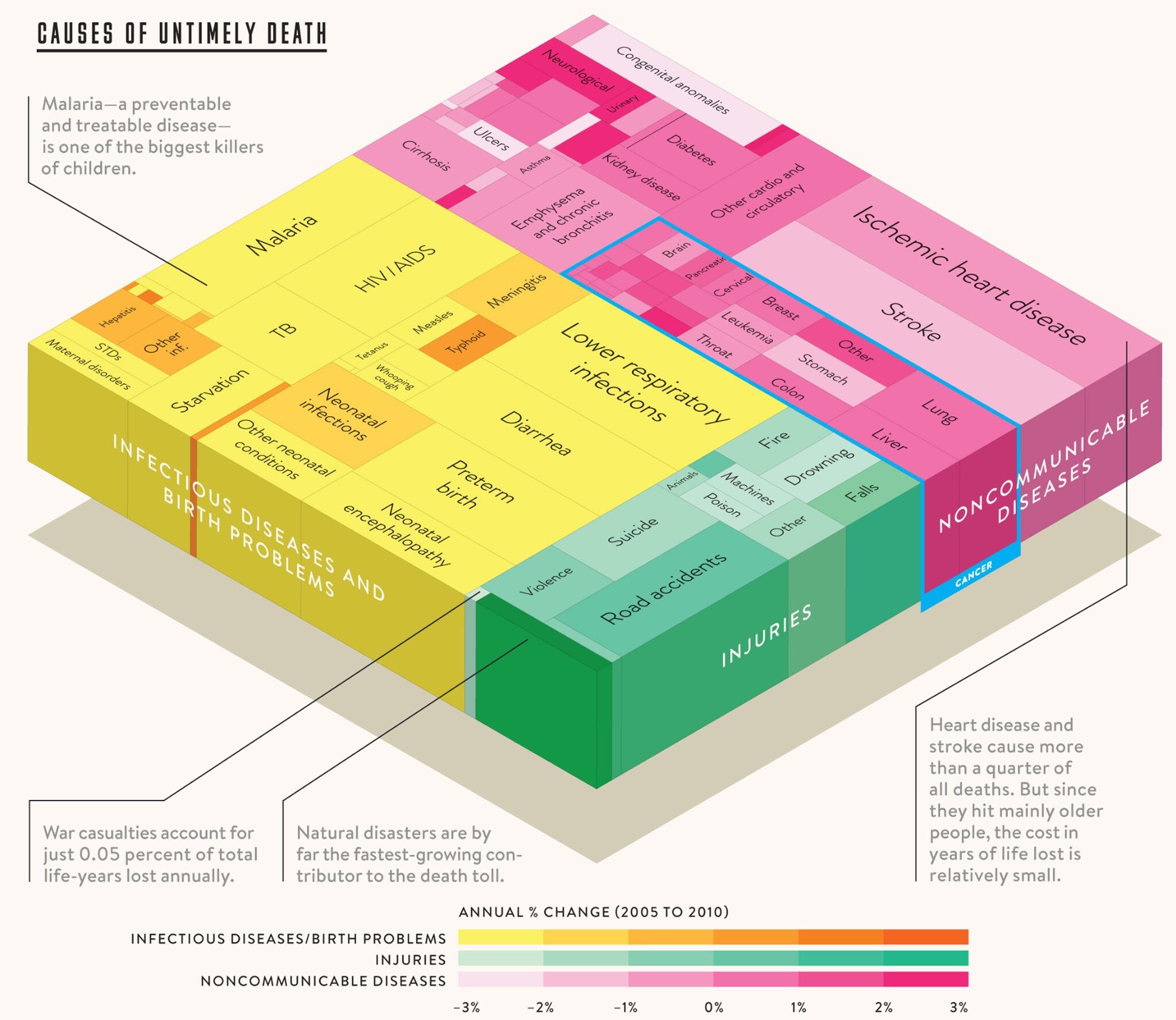

Maybe the reason for the lack of interest of low income tenants in putting batteries and fire alarms is domestic household fires are relatively rare these days. Fire is buried in the green area of the diagram below and is similar to drowning and falls.

The American data below suggests that your chances of dying by fire are about the same as dying from choking and a little worse from dying from post surgery complications.

Rather than in need of nudging, your average low income tenants seems to have it pretty right regarding the risks of dying in a fire.

When I went looking for some economics of housing habitability laws, Google was a bit of a disappointment. There are some empirical work done in the 1970s and early 1980s and then it fell away.

My suspicion is there is not so much empirical work on the economics of housing habitability laws because proving the obvious is not a good investment in Ph.D. topics or tenure track economic research.

Walter Block wrote an excellent defence of slumlords in his 1971 book Defending the Undefendable:

The owner of ghetto housing differs little from any other purveyor of low-cost merchandise. In fact, he is no different from any purveyor of any kind of merchandise. They all charge as much as they can.

First consider the purveyors of cheap, inferior, and second-hand merchandise as a class. One thing above all else stands out about merchandise they buy and sell: it is cheaply built, inferior in quality, or second-hand.

A rational person would not expect high quality, exquisite workmanship, or superior new merchandise at bargain rate prices; he would not feel outraged and cheated if bargain rate merchandise proved to have only bargain rate qualities.

Our expectations from margarine are not those of butter. We are satisfied with lesser qualities from a used car than from a new car. However, when it comes to housing, especially in the urban setting, people expect, even insist upon, quality housing at bargain prices.

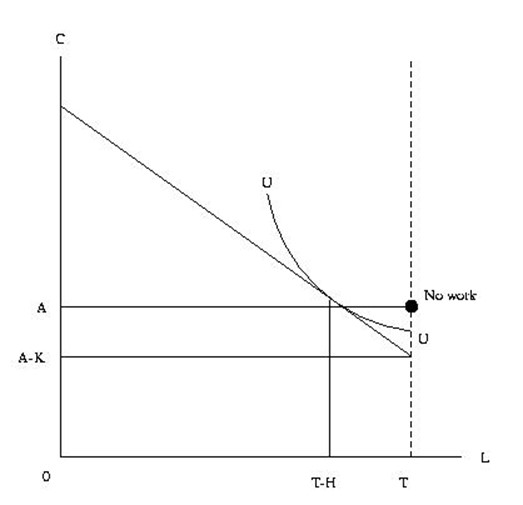

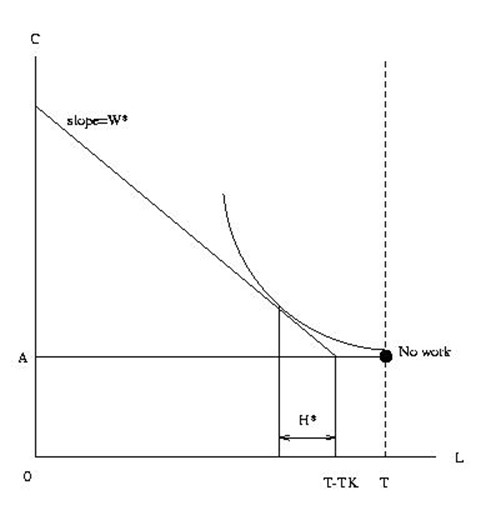

Richard Posner discussed housing habitability laws in his Economic Analysis of the Law. The subsection was titled wealth distribution through liability rules. Posner concluded that habitability laws will lead to abandonment of rental property by landlords and increased rents for poor tenants.

What do-gooder would want to know that a warranty of habitability for rental housing will lead to scarcer, more expensive housing for the poor! Surprisingly few interventions in the housing market work to the advantage of the poor.

Certainly, there will be less rental housing of a habitability standard below that demanded by do-gooders. In the Encyclopaedia of Law and Economics entry on renting, Werner Hirsch said:

It would be a mistake, however, to look upon a decline in substandard rental housing as an unmitigated gain. In fact, in the absence of substandard housing, options for indigent tenants are reduced. Some tenants are likely to end up in over-crowded standard units, or even homeless.

If you’re so smart, why aren’t you rich: Deirdre McCloskey on economists as forecasters

10 Nov 2014 1 Comment

The reversing gender gap: why women choose not to be scientists, engineers and IT professionals

05 Nov 2014 4 Comments

in discrimination, economics of education, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: do gooders, occupation choice, sex discrimination, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Concerns about the lack of women undertaking careers in science and engineering are based on one simple false premise: that science and engineering are the most prestigious choices available to women with great ability in maths and science at high school.

We themed our roundup this week: 5 Plots on Gender You Have to See blog.plot.ly/post/976775676… @randal_olson @katy_milkman http://t.co/B5suLXIPkz—

plotly (@plotlygraphs) September 16, 2014

If relatively more prestigious career options are open to women who also happen to qualify for science and engineering, women will be underrepresented in science and engineering simply because they have better career options than the men who become scientists and engineers.

In New Zealand, just as many women as men qualify for science and engineering and the IT degrees. Not as many women who have qualified take up this option simply because they also qualify for medicine and law in greater numbers than the men who happen to qualify for science, engineering and IT degrees.

In the United States, the Association for Psychological Science found that:

Women may be less likely to pursue careers in science and math because they have more career choices, not because they have less ability, according to a new study published in Psychological Science.

Although the gender gap in mathematics has narrowed in recent decades, with more females enrolling and performing well in math classes, females are still less likely to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) than their male peers.

Researchers tend to agree that differences in math ability can’t account for the underrepresentation of women in STEM fields. So what does?

Developmental psychologist Ming-Te Wang and his colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh and University of Michigan wondered whether differences in overall patterns of math and verbal ability might play a role.

The researchers examined data from 1490 college-bound US students drawn from a national longitudinal study. The students were surveyed in 12th grade and again when they were 33 years old. The survey included data on several factors, including participants’ SAT scores, various aspects of their motivational beliefs and values, and their occupations at age 33.

Looking at students who showed high math abilities, Wang and colleagues found that those students who also had high verbal abilities — a group that contained more women than men — were less likely to have chosen a STEM occupation than those who had moderate verbal abilities.

This outcome is no surprise for those familiar with the gap between men and women in verbal and reading abilities – a gap that is strongly in favour of women

The OECD PISA tests at the age of 15 find that teenage boys have a slight advantage in maths – a few percentage points – teenage girls have a serious advantage in reading.

The OECD PISA tests at the age of 15 find that this superior verbal and reading abilities of teenage girls the equivalent of six months extra schooling. One half year’s education goes a long way towards explaining many wage gaps by gender,ethnicity in race. This six-month edge in schooling is a serious advantage when qualifying for university.

Young women choose to not pursue science, engineering and IT careers because there are other career options that allow them to use their superior verbal and reading abilities – other careers is that allow them to be more successful in life than being a scientist, an engineer or an IT geek. As the Association for Psychological Science explains in the same press release cited above:

Our study shows that it’s not lack of ability or differences in ability that orients females to pursue non-STEM careers, it’s the greater likelihood that females with high math ability also have high verbal ability,” notes Wang. “Because they’re good at both, they can consider a wide range of occupations.

To put it bluntly, science, engineering and IT degrees are for young people who lack the verbal and reading abilities to get into medicine and law. Science, engineering and IT good degrees are for those who can’t get into medicine and law. They could have been contenders if they were more articulate and well-read.

There is a gender disparity in science, engineering and IT because teenage girls find these degrees to be inferior choices – inferior choices given the set of abilities they have when considering their career options.

HT: Mark J. Perry

The real reason why behavioural economics is so popular among politicians and bureaucrats

03 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, behavioural economics, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: behavioural economics, do gooders, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

\

\

HT: David-k-Levine

Recent Comments