Source: The World Wealth and Income Database.

The rise of the Canadian working rich – composition of top 1% incomes since 1946

08 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, human capital, labour economics, poverty and inequality Tags: Canada, superstar wages, superstars, top 1%, working rich

The New Zealand top 1% is still bone lazy – top 1% income shares USA, New Zealand and Australia since 1913

08 Jan 2016 2 Comments

in applied price theory, economic history, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, poverty and inequality Tags: Australia, Leftover Left, top 1%

What slackers. Despite 30 years of neoliberalism oppressing the unions and working class, the top 1% in New Zealand (and Australia) are unable to do any better in terms of their share of national income than in the good old days of pre-1984 New Zealand looked upon with such fondness by the the Leftover Left.

Source: The World Wealth and Income Database.

Top 1% pays almost as much tax as the bottom 95%

27 Dec 2015 1 Comment

in politics - USA, public economics Tags: top 1%

The gender gap among the top 1%

19 Dec 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: gender wage gap, superstar wages, superstars, top 1%

Why didn’t @MaxRashbrooke chart the top 1%’s wealth?

10 Dec 2015 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, Marxist economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: top 1%, Twitter left

The latest research of Max Rashbrooke on trends in wealth was in the Dominion Post today. The breathless reporter used it to say that:

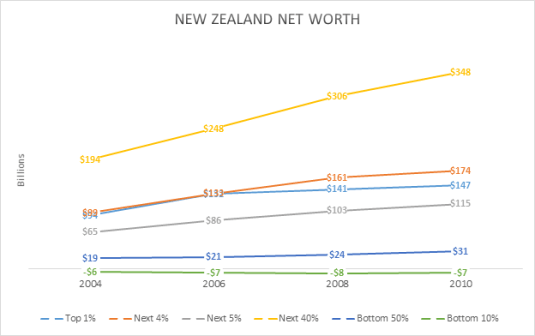

The elite and high-income earners of New Zealand have increased their wealth by almost $200 billion while debt among the poorest has climbed to $7b…

The net wealth of the top 10 per cent has increased dramatically while the bottom 10 per cent of Kiwis face increasing levels of debt in the billions of dollar…

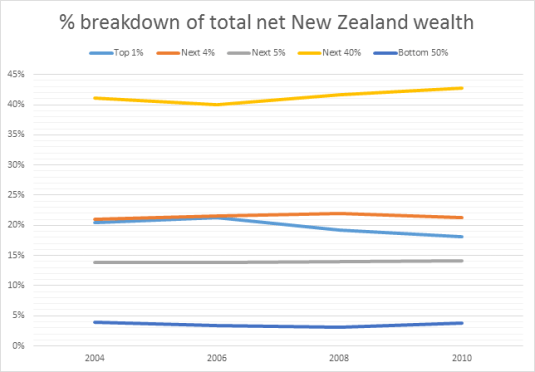

The data in the Dominion Post today consisted of a time series of the top 10% and the bottom 10% share of net wealth and an interactive pie chart showing the distribution of wealth.

When you chart the data published by Max Rashbrooke as a time series rather than an interactive pie chart, today is not quite the day for the down-trodden proletariat to kick in the rotten door of neoliberal capitalism to start the permanent revolution.

It is not much of a call to the barricades to say that just about every section of New Zealand society became much richer in a short six-year period – their wealth increased by between 60-80% between 2004 and 2010 as shown in the chart below. The middle class has been doing just swimmingly between 2004 and 2010: up from $194 billion to $348 billion in a short six years. This is an increase of 80% in six years. So rapid an increase that the sceptics among you might start to doubt the accuracy of the data either at the beginning or by the end.

Furthermore, no section of society noticeably increased their share of wealth as shown in the chart below. Further evidence of how lazy is the top 1% is in New Zealand. Their wealth increased only by 56% between 2004 and 2010. Having the wealth of the top 1% increase by less than every group in society bar the bottom 10% qualifies as a dramatic increase in inequality by the journalistic standards of the Dominion Post. The wealth of the top 10% increased between 2004 and 2010 by 68% – no more than any other group in society bar the top bottom 10%. That too is a dramatic increase in inequality by Dominion Post standards.

Source: Geoff Rashbrooke, Max Rashbrooke and Wilma Molano, Wealth Disparities in NZ Institute for Governance and Policy Studies (November 2015) via The richest 10 per cent own $436 billion of New Zealand’s wealth: research | Stuff.co.nz.

Joan Robinson in the 1940s was on to this failure of capitalism to impoverish the proletarian when she said the battle cry of Marxists would have to change from the 1848 version “rise up ye workers, rise up for you have nothing to lose but your chains” to “rise up ye workers, rise up for you have nothing to lose but the prospect of a suburban home and a motorcar”.

Today that battle cry of the Marxist revolution would have to be “rise up ye workers rise up for you have nothing to lose but your iPhone and your air points”. As Joan Robinson observed in the 1940s, that’s not much of a basis for a revolutionary movement.

The Twitter Left are grumpy buggers because a rapid increase in wealth that is broad-based across New Zealand society – lifting up 90% of New Zealand society – for them is only another reason to complain.

What does @Walmart do wrong but @APPLEOFFIClAL does right?

16 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, politics - USA Tags: Apple, creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness, Left-wing hypocrisy, Leftover Left, superstar wages, superstars, top 1%, Twitter left, Walmart

@CloserTogether @FairnessNZ nail case for neoliberalism @chrishipkins @Maori_Party

06 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in econometerics, economic history, labour economics, labour supply, minimum wage, politics - USA, unions Tags: conspiracy theories, conspiracy theorists, Leftover Left, living standards, Maori economic development, neoliberalism, top 1%, Twitter left, union power, union wage premium

The Council of Trade Unions and Closer Together Whakatata Mai charted similar statistics to show that everything has gone to hell in a hand basket since neoliberalism seized power in New Zealand in 1984 and in particular after the passing of the Employment Contracts Act in 1991.

Source: Income Gap | New Zealand Council of Trade Unions – Te Kauae Kaimahi.

The passage of the Employment Contracts Act greatly reduced union power and union membership and with it wages growth in New Zealand, according to what is left of the New Zealand union movement.

Source: Income Gap | New Zealand Council of Trade Unions – Te Kauae Kaimahi.

Unfortunately, both charts of the same statistics show the exact opposite to what was intended by The Council of Trade Unions and Closer Together Whakatata Mai.

Even the most casual inspection of the data charted above and reproduced below with some annotations shows that real wages growth returned to New Zealand in the early 1990s after 20 years of real wage stagnation.

Source: Income Gap | New Zealand Council of Trade Unions – Te Kauae Kaimahi.

The reforms of the 1980s stopped what was a long-term decline in average real wages. The reforms of the early 1990s including the passing of the Employment Contracts Act was followed by the resumption of sustained growth in average real wages with little interruption since.

Closer Together Whakatata Mai has even stumbled onto the great improvements in household incomes across all ethnicities since the early 1990s.

The increase in percentage terms of Maori and Pasifika real household income is much larger than for Pakeha. As Bryan Perry (2015, p. 67) explains when commenting on the very table D6 sourced by Closer Together Whakatata Mai:

From a longer-term perspective, all groups showed a strong rise from the low point in the mid 1990s through to 2010. In real terms, overall median household income rose 47% from 1994 to 2010: for Maori, the rise was even stronger at 68%, and for Pacific, 77%. These findings for longer- term trends are robust, even though some year on year changes may be less certain. For 2004 to 2010, the respective growth figures were 21%, 31% and 14%.

Source: Bryan Perry, Household Incomes in New Zealand: trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2014 – Ministry of Social Development, Wellington (August 2015), Table D6.

As Closer Together Whakatata Mai documented, incomes increased in real terms by 14% for the bottom and 19% for the middle.

Perry noted that in the lowest decile had too many implausible incomes including many on zero income so he was wary of relying on it. I have therefore charted the second, median and top decile before and after housing costs below. All three deciles charted showed substantial improvements in incomes both before and after housing costs.

Source: Bryan Perry, Household Incomes in New Zealand: trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2014 – Ministry of Social Development, Wellington (August 2015).

Naturally, measuring changes in living standards over long periods of time is fraught with under-estimation. There are new goods to be accounted for and product upgrades too.

The apps in your smartphone cost $900,000 thirty years ago —@datarade https://t.co/pjw7q4QGDp—

Vala Afshar (@ValaAfshar) October 29, 2015

Swedish and Danish top incomes & union decline @FlipChartRick @EconomicPolicy @PoliticalSift

04 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, econometerics, entrepreneurship, labour economics, Public Choice, rentseeking, unions Tags: Denmark, labour surplus, Sweden, top 1%, union power, union wage premium

The Danish top 1% and top 10% is even lazier than their transnational co-conspirators. No success at all at either grinding the Danish unions down or extracting more labour surplus from the long-suffering Danish proletariat.

Source: OECD StatExtract and Top Incomes Database.

Source: OECD StatExtract and Top Incomes Database.

The Swedish top 10% and top 1% have done a bit better since the economic liberalisation in that country from the early 1990s. But none of that additional labour surplus has anything to do with grinding the unions down because Swedish union membership has not declined.

Source: OECD StatExtract and Top Incomes Database.

Source: OECD StatExtract and Top Incomes Database.

Top incomes and the decline of unions in Canada, France and Italy

03 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economic history, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, labour economics, labour supply, Milton Friedman, poverty and inequality, Public Choice, rentseeking, unions Tags: Canada, entrepreneurial alertness, France, Italy, top 1%, union power, union wage premium

The French ruling class is as lazy as their transnational co-conspirators down under. French union membership is in serious decline albeit from a low base. An opportunity lost for the French ruling class. It has not lifted a finger to extract additional labour surplus from the downtrodden French proletariat now stripped of their only line of collective defence against capitalist exploitation.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

The top 10% and top 1% in France are no better off than two generations ago despite the decline of French unions. The French Left must be most disappointed. No kicking in the rotten door of the permanent revolution anytime soon after the immiserised French proletariat rises up because it has nothing to lose but its chains. The 21st century version of the Marxist call to the barricades would be a proletariat stirred to revolution with nothing to lose but their suburban home, motorcar, IPad and air points

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

The Italian ruling class has had little success in bringing Italian unions down. The top 10% in Italy is earning no more now than back when the Red Brigades were gunning for them.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

The top 1% in Italy is doing a little bit better than when the Red Brigade was gunning for them, but not much more. Unions don’t figure in explaining that small rise in Italian top 1% incomes over the last 40 years. Italian unions are pretty much a strong as they were 40 years ago in membership. Italian employment protection laws are pretty much as strong as they used to be too.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

The Canadian ruling classes even more incompetent than their transnational co-conspirators over in Italy. There appears to have been next to no decline in union membership in Canada. The Canadian top 10% is not earning any more than back in the 60s.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

The Canadian top 1% is doing a little bit better than 25 years ago also but not off the back of unions which are almost as strong as in the past. The Canadian Left will have to look for a different hypothesis than the ravages of the top 1%.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

All in all, the Economic Policy Institute simply got lucky with a spurious correlation between top incomes and union membership in the USA.

@EconomicPolicy showed gender pay equality when arguing the opposite @CHSommers @Mark_J_Perry

02 Nov 2015 2 Comments

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - USA Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, compensating differentials, gender wage gap, marital division of labour, power couples, top 1%, top incomes, Twitter left, union power, union wage premium

The Economic Policy Institute were good enough to dig out unit record data on the unadjusted US gender wage gap by percentiles. In attempting to show there was a persistent gender pay gap, the impeccably left-wing Economic Policy Institute showed that the unadjusted gender pay gap has all but disappeared in the USA.

There is next to no gender wage gap even in unadjusted terms towards the bottom of the labour market. This is despite all the protestations of the Left of an inherent inequality of bargaining power between the bosses and workers.

The low paid are supposed to be powerless unless unionised. Declining unionisation is a leading explanation on the Left of the rising income shares of the top 10%, top 1% in the top 0.1%.

If that inherent inequality of bargaining power trundled out at every opportunity by the Twitter Left explains anything in the labour market, this inequality of bargaining power should be operating with greatest strength at the bottom of the labour market.

Clearly the inherent inequality of bargaining power between the bosses and workers is not doing its job regarding the gender wage gap. The gender wage gap in the USA increases as you move up the income ladder rather than the other way around.

The explanation of the Economic Policy Institute for greater gender pay equality at the bottom is the minimum wage and male wage stagnation:

It is interesting to note that the wage gap between genders is smaller at the 10th percentile than at the 95th. At the 10th percentile, women earn 91 percent of men’s wages while women make only 79 percent of men’s wages at the 95th percentile.

The minimum wage is partially responsible for this greater equality among the lowest earners—it sets a wage floor that applies to everyone, which means that people near the bottom of the distribution are likely to make more equal wages. Also, low-wage workers are disproportionately women, which means that the minimum wage particularly bolsters women’s wages.

…Although women have seen modest wage gains in the last several decades, the main reason the gender wage gap has slowly narrowed is that the vast majority of men’s wages have stagnated or declined.

It is a bit rich for the Economic Policy Institute to praise the minimum wage as a force for increasing incomes after spending so much of its time saying how the minimum wage has fallen way behind wages growth in general.

The gender gap lingers at the top of the labour market despite the quite substantial wage gains for women as compared to men over the past 15 years. The Economic Policy Institute dismissed the substantial gains as modest despite their own documenting of them.

It is even richer for the Economic Policy Institute to start extending the male wage stagnation hypothesis to the top 20% and top 10%.

The top of the income distribution has not been known previously known as victims of wage stagnation.

The gender wage gap remains stubbornly high at the top end of the US labour market at 20% for the last few decades. The gender wage is so large and has stayed large at the top half of the labour market for the past few decades because of compensating differentials. Women on higher incomes are balancing families and careers in choosing the occupations that best suits each individual woman, their talents and educational choices.

Source: OECD Employment Database.

Studies of top earning professionals show that they make quite deliberate choices between family and career. The better explanation of why so many women are in a particular occupation is job sorting: that particular job has flexible hours and the skills do not depreciate as fast for workers who take time off, working part-time or returning from time out of the workforce. Low job turnover workers will be employed by firms that invest more in training and job specific human capital.

- Higher job turnover workers, such as women with children, will tend to move into jobs that have less investment in specialised human capital, and where their human capital depreciates at a slower pace.

- Women, including low paid women, select careers in jobs that match best in terms of work life balance and allows them to enter and leave the workforce with minimum penalty and loss of skills through depreciation and obsolescence.

This is the choice hypothesis of the gender wage gap. Women choose to educate for occupations where human capital depreciates at a slower pace. This gender wage gap for professionals can be explained by the marriage market combined with assortative mating:

- Graduates are likely to marry each other and form power couples; and

- There tends to be an age gap between men and women in long-term relationships and marriages of two years.

This two-year age gap means that the husband has two additional years of work experience and career advancement. This is likely to translate into higher pay and more immediate promotional prospects. Maximising household income would imply that the member of the household with a higher income, and greater immediate promotional prospects stay in the workforce.

This is consistent with the choice hypothesis and equalising differentials as the explanation for the gender wage gap. As Solomon Polachek explains:

At least in the past, getting married and having children meant one thing for men and another thing for women. Because women typically bear the brunt of child-rearing, married men with children work more over their lives than married women. This division of labour is exacerbated by the extent to which married women are, on average, younger and less educated than their husbands.

This pattern of earnings behaviour and human capital and career investment will persist until women start pairing off with men who are the same age or younger than them.

In low-paying jobs, there is little in the way of trade-offs other than full-time or part-time work. Low-paid jobs do not involve choosing majors at university, choosing careers, industries and employers that call for long hours and uninterrupted careers or not so long hours, fewer human capital and promotional penalties for time off and more work-life balance. The choice hypothesis is the far better explanation for the persistence of the unadjusted gender wage gap in the USA as Polachek explains:

The gender wage gap for never marrieds is a mere 2.8%, compared with over 20% for marrieds. The gender wage gap for young workers is less than 5%, but about 25% for 55–64-year-old men and women.

If gender discrimination were the issue, one would need to explain why businesses pay single men and single women comparable salaries. The same applies to young men and young women. One would need to explain why businesses discriminate against older women, but not against younger women. If corporations discriminate by gender, why are these employers paying any groups of men and women roughly equal pay?

Why is there no discrimination against young single women, but large amounts of discrimination against older married women? … Each type of possible discrimination is inconsistent with negligible wage differences among single and younger employees compared with the large gap among married men and women (especially those with children, and even more so for those who space children widely apart)

The main drivers of the gender wage gap are unknown to employers such as whether the would-be recruit or employer is married, their partner is present, how many children they have, how many of these children are under 12, and how many years are there between the births of their children.

@economicpolicy Top incomes and the decline of unions in the US, UK, Australia and New Zealand

02 Nov 2015 4 Comments

in applied welfare economics, labour economics, Marxist economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, unions Tags: top 1%, union power, union wage premium

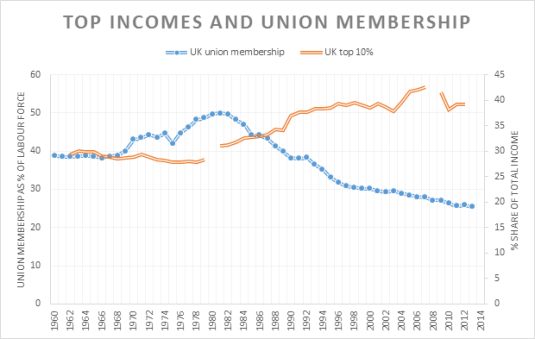

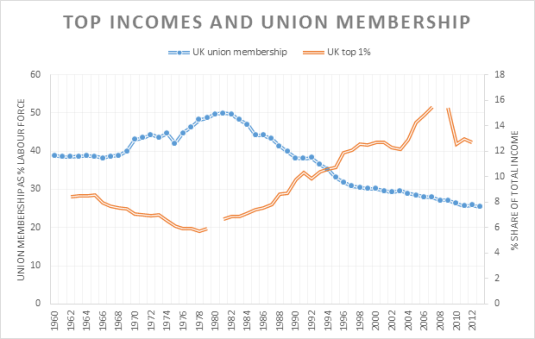

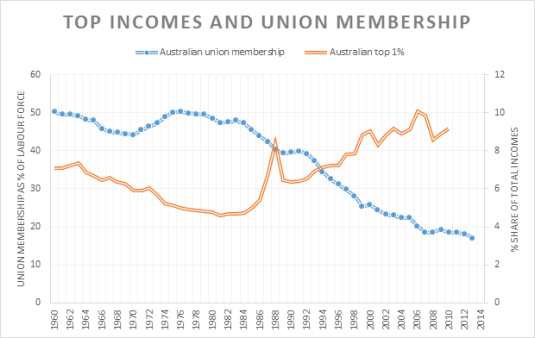

The Left in the USA and the UK like to show correlations between top incomes and the decline of union membership.

I thought I would check how this hypothesis travelled to European offshoots such as Australia and New Zealand. For example, in the USA, top income shares have been increasing while union membership has been in decline since 1960.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

In the UK, the relationship between union membership and top incomes is gentler than in the USA.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

Moving down under, the relationship between top incomes and union membership is non-existent in New Zealand.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

The same pretty much goes for Australia in terms of no relationship between top incomes in union membership to extent that this relationship is anything more than a spurious correlation.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

Source: OECD Stat and Top Incomes Database.

@MaxCRoser the impact of the top 1% on Swedish economic growth

25 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic growth, economic history, macroeconomics, Marxist economics Tags: endogenous growth theory, envy, Leftover Left, politics of envy, Sweden, top 1%

#Sweden: Inequality decreased hugely in the 20th century – but is now rising.

bit.ly/1DEBY1P https://t.co/MHPgp29AWZ—

Max Roser (@MaxCRoser) October 24, 2015

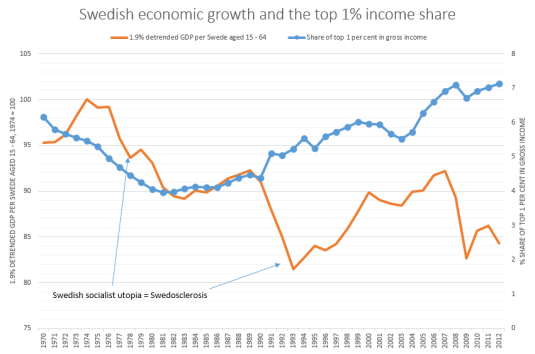

A fall in the share of the top 1% of total Swedish total incomes was in tune with the emergence of a new word in the English language which was Swedosclerosis. That was the long stagnation in the Swedish economy in the 1970s and the 1980s with Swedish economic growth well below that in the trend rate of growth in the USA. Only after an increase in the top 1% share in Sweden did economic growth start recovering to trend.

Source: Computed from OECD StatExtract and The Conference Board. 2015. The Conference Board Total Economy Database™, May 2015, http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/

In the chart above, a flat-line in real GDP per working age Swede is growth at the trend rate of the US economy for the 20th century which was 1.9% per year. A falling line is Swedish growth below trend, a rising line is growth above that trend rate of 1.9% in Sweden. A trend rate of 1.9% is the trend rate of growth currently used by Edward Prescott for the USA in the 20th century.

More evidence on the emergence of the working rich

25 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of education, entrepreneurship, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, Marxist economics, occupational choice Tags: College premium, creative destruction, education premium, entrepreneurial alertness, graduate premium, Leftover Left, superstar wages, superstars, top 1%

@BernieSanders are the rich getting richer & poor getting poorer or are just men getting their comeuppance?

16 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, politics - USA Tags: 2016 presidential election, expressive voting, gender wage gap, Leftover Left, middle class stagnation, reversing gender gap, top 1%, Twitter left, wage stagnation

The Typical Male U.S. Worker Earned Less in 2014 Than in 1973: blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2015/… http://t.co/PmTmmfsfbE—

Demos Action (@DemosAction) September 21, 2015

For the first time ever, women are more likely to have bachelor's degrees than men. vox.com/2015/10/13/951… http://t.co/ffK7iiU2Kq—

Demos (@Demos_Org) October 14, 2015

Recent Comments