The principle of competitive land supply – Anthony Downs

16 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, urban economics Tags: Anthony Downs, green rent seeking, housing affordability, land supply, land use regulation, NIMBYs, offsetting behaviour, RMA, unintended consequences

Offsetting behaviour: smoking and obesity

16 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, health economics Tags: economics of obesity, economics of smoking, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

US life-expectancy finding: Rise in obesity has nearly offset the decline in smoking nber.org/aginghealth/20… http://t.co/VJ2zvvSisv—

Derek Thompson (@DKThomp) May 15, 2015

Urban planners are confident souls

15 May 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, economics of regulation, environmental economics, growth miracles, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, urban economics Tags: green rent seeking, housing affordability The fatal conceit, land use regulation, offsetting behaviour, RMA, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences, urban planning, zoning

Why is the gender gap so large and the glass ceiling so thick in Sweden?

14 May 2015 1 Comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, human capital, labour economics, occupational choice, politics - USA Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, do gooders, economics of families, gender wage gap, maternity leave, Sweden, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

The gender wage gap is no better than the OECD average, despite generous maternity and paternity leave. What gives?

America: one day a year celebrating mothers, fathers.

Sweden: 480 days paid leave per child. vox.com/2014/5/12/5708… http://t.co/weFDrTj7Jb—

Ezra Klein (@ezraklein) May 11, 2015

Source: Closing the gender gap: Act now – http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264179370-en

How big is the wage gap in your country? bit.ly/18o8icV #IWD2015 http://t.co/XTdntCRfDQ—

(@OECD) March 08, 2015

One important question is whether government policies are effective in reducing the gap. One such policy is family leave legislation designed to subsidize parents to stay home with new-born or newly adopted children.

One of the RLE articles shows that for high earners in Sweden there is a large difference between the wages earned by men and women (the so-called “glass ceiling”), which is present even before the first child is born. It increases after having children, even more so if parental leave taking is spread out.

These findings suggest that the availability of very long parental leave in Sweden may be responsible for the glass ceiling because of lower levels of human capital investment among women and employers’ responses by placing relatively few women in fast-track career positions. Thus, while this policy makes holding a job easier and more family-friendly, it may not be as effective as some might think in eradicating the gender gap.

via New volume on gender convergence in the labour market | IZA Newsroom.

The crusade to ban e-cigarette had the predictable effect among teens

12 May 2015 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, health economics Tags: do gooders, economics of smoking, meddlesome preferences, nanny state, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

Teen e-cigarette consumption has surpassed conventional smoking in 2014 #vaping via @CDCgov

statista.com/chart/3417/eci… http://t.co/RnZz1nbj5X—

Statista (@StatistaCharts) April 22, 2015

The Ten Pillars of Economic Wisdom

10 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, Austrian economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, development economics, economic history, economics of education, economics of information, economics of media and culture, economics of regulation, energy economics, entrepreneurship, financial economics, health economics, history of economic thought, industrial organisation, survivor principle Tags: David Anderson, evidence-based policy, offsetting behaviour, pretence to knowledge, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

via The Ten Pillars of Economic Wisdom, David Henderson | EconLog | Library of Economics and Liberty.

FA Hayek on piecemeal analysis such as cost benefit analysis and evidence-based policy

09 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, Austrian economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economics of regulation, F.A. Hayek Tags: Constitution of Liberty, cost benefit analysis, evidence-based policy, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

Happy Birthday, F.A. Hayek!

(8 May 1899 – 23 March 1992) http://t.co/K431Kj9nok—

Screwed by State (@ScrewedbyState) May 09, 2015

Milton Friedman on evidence-based policy

27 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, Milton Friedman Tags: evidence-based policy, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

No one says this about economists

27 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, Austrian economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, F.A. Hayek, liberalism, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: evidence-based policy, offsetting behaviour, science and public policy, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

Scientists dream about what could be.

Economists remind you of price tags and unintended consequences

Richard Posner on libertarian scepticism about law as an engine of women’s liberation

25 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

The Times of London on the fatal conceit, the pretence to knowledge and unintended consequences

27 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

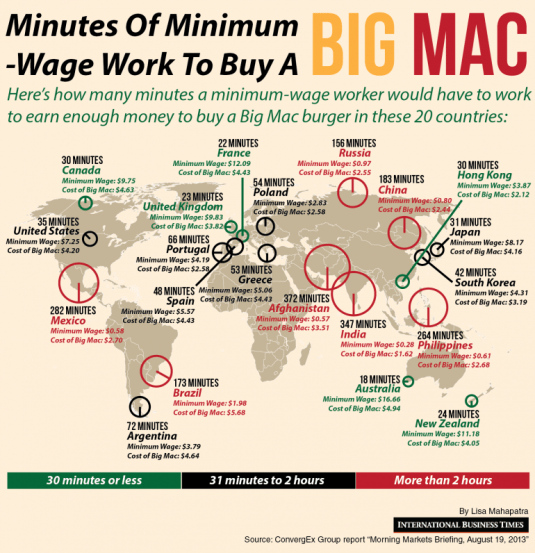

Offsetting behaviour alert: only fools and politicians would believe that a minimum wage increase increases net pay and conditions

20 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in income redistribution, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: minimum wage, offsettinh behaviour, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

John Schmitt lists 11 margins along which a minimum wage might cause changes in net pay and conditions:

- Reduction in hours worked (because firms faced with a higher minimum wage trim back on the hours they want),

- Reduction in non-wage benefits (to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage),

- Reduction in money spent on training (again, to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage),

- Change in composition of the workforce (that is, hiring additional workers with middle or higher skill levels, and fewer of those minimum wage workers with lower skill levels),

- Higher prices (passing the cost of the higher minimum wage on to consumers),

- Improvements in efficient use of labour (in a model where employers are not always at the peak level of efficiency, a higher cost of labour might give them a push to be more efficient),

- “Efficiency wage” responses from workers (when workers are paid more, they have a greater incentive to keep their jobs, and thus may work harder and shirk less),

- Wage compression (minimum wage workers get more, but those above them on the wage scale may not get as much as they otherwise would),

- Reduction in profits (higher costs of minimum wage workers reduces profits),

- Increase in demand (a higher minimum wage boosts buying power in overall economy), and

- Reduced turnover (a higher minimum wage makes a stronger bond between employer and workers, and gives employers more reason to train and hold on to worker.

Richard McKenzie argues that the biggest impact of a minimum wage increase is reductions to paid and unpaid benefits for minimum wage workers, including health insurance, store discounts, free food, flexible scheduling, and job security resulting from higher-skilled workers drawn to the higher minimum wage jobs:

- Masanori Hashimoto found that under the 1967 minimum-wage hike, workers gained 32 cents in money income but lost 41 cents per hour in training—a net loss of 9 cents an hour in full-income compensation.

- Other researchers in independently completed studies found more evidence that a hike in the minimum wage undercuts on-the-job training and undermines covered workers’ long-term income growth.

- Wessels found that the minimum wage caused retail establishments in New York to increase work demands by cutting back on the number of workers and giving workers fewer hours to do the same work.

- Fleisher, Dunn, and Alpert found that minimum-wage increases lead to large reductions in fringe benefits and to worsening working conditions.

- Marks found that workers covered by the federal minimum-wage law were also more likely to work part time, given that part-time workers can be excluded from employer-provided health insurance plans.

McKenzie also argued that if the minimum wage does not cause employers to make substantial reductions in fringe benefits and increases in work demands, then an increased minimum should cause

(1) An increase in the labour-force-participation rates of covered workers (because workers would be moving up their supply of labour curves),

(2) A reduction in the rate at which covered workers quit their jobs (because their jobs would then be more attractive), and

(3) A significant increase in prices of production processes heavily dependent on covered minimum-wage workers.

Wessels found that minimum-wage increases had exactly the opposite effect as intended: labour force participation rates went down; job quit rates went up, and prices did not rise appreciably.

These are findings by Wessels are consistent only with the view that minimum-wage increases make workers worse off, rather than better off in terms of net pay and conditions. After the minimum wage increase, the net advantages and disadvantages of menial jobs are less than before. Fewer workers enter the workforce and more quit their jobs.

McKenzie was the first economist to argue that a minimum wage increase may actually reduce the labour supply of menial workers. Employment in menial jobs may go down slightly in the face of minimum-wage increases not so much because the employers don’t want to offer the jobs, but because fewer workers want these menial jobs that are offered.

The repackaging of monetary and non-monetary benefits, greater work intensities and fewer training opportunities make these jobs less attractive relative to their other options. This reduction in labour supply by low skilled workers is why the voluntary quit rate among low-wage workers goes up, not down, after a minimum wage increase. As McKenzie explains

Economists almost uniformly argue that minimum wage laws benefit some workers at the expense of other workers.

This argument is implicitly founded on the assumption that money wages are the only form of labour compensation. Based on the more realistic assumption that labour is paid in many different ways, the analysis of this paper demonstrates that all labourers within a perfectly competitive labour market are adversely affected by minimum wages.

Although employment opportunities are reduced by such laws, affected labour markets clear. Conventional analysis of the effect of minimum wages on monopsony markets is also upset by the model developed.

McKenzie argues that not accounting for offsetting behaviour led to a fundamental misinterpretation in the empirical literature on the minimum wage. That literature shows that small increases in the minimum wages does not seem to affect employment and unemployment by that much.

…. wage income is not the only form of compensation with which employers pay their workers. Also in the mix are fringe benefits, relaxed work demands, workplace ambiance, respect, schedule flexibility, job security and hours of work.

Employers compete with one another to reduce their labour costs for unskilled workers, while unskilled workers compete for the available unskilled jobs — with an eye on the total value of the compensation package.

With a minimum-wage increase, employers will move to cut labour costs by reducing fringe benefits and increasing work demands

Proponents and opponents of minimum-wage hikes do not seem to realize that the tiny employment effects consistently found across numerous studies provide the strongest evidence available that increases in the minimum wage have been largely neutralized by cost savings on fringe benefits and increased work demands and the cost savings from the more obscure and hard-to-measure cuts in nonmoney compensation.

McKenzie is correct in arguing that the empirical literature on the minimum wage is dewy-eyed. The first assumption about any regulation is the market will offset it significantly.

In the course of undoing the direct effects of the regulation, there will be unintended consequences such as the remixing of wage and nonwage components of remuneration packages of low skilled workers covered by the minimum wage. Greg Mankiw concludes that:

The minimum wage has its greatest impact on the market for teenage labour. The equilibrium wages of teenagers are low because teenagers are among the least skilled and least experienced members of the labour force.

In addition, teenagers are often willing to accept a lower wage in exchange for on-the-job training. . . . As a result, the minimum wage is more often binding for teenagers than for other members of the labour force.

Recent Comments