Everybody Hates Chris, “Everybody Hates Food Stamps” (2005)

27 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, TV shows, welfare reform Tags: Everybody Hates Chris, food stamps, welfare reform

Chapple and Boston on the extent of welfare benefit fraud in New Zealand

22 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of crime, labour economics, law and economics, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, crime and punishment, deterrence, Jonathan Boston, Simon Chapple, welfare fraud, welfare reform

What is more surprising about this honest disclosure of welfare fraud to the Household Labour Force Survey of Statistics New Zealand in 2011 is these welfare beneficiaries were so upfront about their criminal fraud.

These estimates must underestimate the extent of welfare fraud because some of these criminals would be aware that they should be slightly discreet in the company of any government official when discussing their eligibility for welfare benefits and any false information supplied in their claims for welfare benefits.

Some welfare cheats are alert to this basic criminal skill and do not claim their benefit if called in to the welfare benefits office for a reassessment of their eligibility. They don’t have the front to go near a government official while defrauding the taxpayer.

Yes, welfare fraud is a crime so people who perpetrated these crimes by obtaining welfare benefits under false pretences are criminals. If these criminals are caught, they are prosecuted for a crime and sometimes sent to prison.

HT: Muriel Newman

Is welfare dependence optimal for whom – part 7: the role of tagging in welfare benefits system

16 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in economics of love and marriage, labour economics, labour supply, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, labour supply, poverty and inequality, welfare reform

The unambiguously favourable labour supply effects of work requirements are often contrasted with the ambiguous results of changes in benefit abatement regimes.

The twist is work requirements need to be accompanied by a categorisation of the welfare population into those who can work and those who cannot work. The latter do need welfare support because they are unable to earn a wage in the labour market or have carer responsibilities such as for pre-schoolers.

There is already a large population on other welfare benefits with short and long-term barriers to work because of sickness or invalidity classifications.

The favourable labour supply effects of work requirements depend on an ability to adequately categorise the welfare population into different groups. The large differences between otherwise comparable countries in the number on sickness and disability benefits suggest that this classification and sorting process is knowledge intensive and error prone.

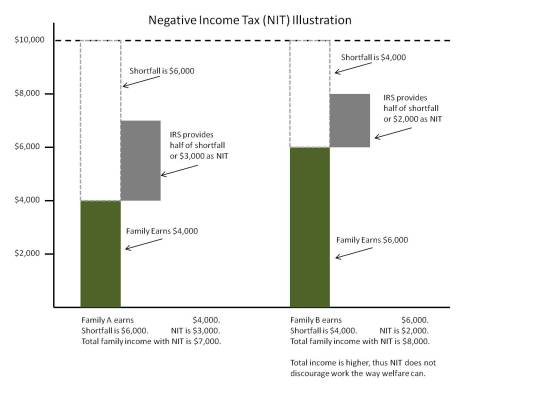

The original support for negative income taxes from Friedman (1962) and Stigler (1946) was born of the notion that welfare bureaucracies are unable to adequately screen, categorise and tag welfare claimants by their capacity to work and diligent job search in a dynamic world with dispersed knowledge and moral hazard.

Negative income taxes were proposed as an administratively simple welfare reform to give adequate income support to the low paid, out of work and unable to work, while still providing reasonable work incentives for the low paid. The negative income tax was originally intended to replace existing welfare benefits for families at least.

The modern incarnations of negative income taxes manifest as in-work tax credits that supplement welfare benefits and reduce poverty among the working poor.

The ambiguous effect of negative income taxes on the net labour supply among the low-paid was acknowledged at the outset, and was borne out in experimental trials and experience with in-work tax credits.

The existing system of domestic purpose, unemployment, sickness and invalid benefits are all examples of screening, categorising and tagging of welfare claimants with varying degrees of success.

The tagging is based on relatively coarse screening devices such as job loss, sole parenthood and medical grounds.

Akerlof (1978) noted that the truly needy—those with low job skills who have extreme difficulty in becoming employed—can be partly identified by some measurable, observable characteristic, which he called tagging the poor. Some combination of indications of poor health, low levels of education and spotty employment histories might be indicators of low job skills.

If the government moves from a negative income tax, in which all those with income are paid benefits regardless of their characteristics, to a tagged system in which only the subset who have the particular set of characteristics indicating that they are needy are paid benefits, then higher benefits could be paid to the tagged individuals without changing total expenditure.

Depending on whether the welfare tag is job loss, sole parenthood, sickness or invalidity, different abatement regimes, benefit levels and work tests apply. ACC is another example of tagging with the screening based on accidental injury.

Most welfare systems tag Akerlof partly with family structure in mind as a characteristic, with benefits heavily concentrated on families with a single parent.

Family tax credits are based on tagging through the number of hours worked and the number of children that are dependent upon the wage earner.

Nichols and Zeckhauser (1982) argued that the imposition of “ordeals” on welfare recipients, of which work requirements were one example, but onerous application procedures and participation requirements are others, could serve to deter entry of the able-bodied.

The experience with tagging to date suggest that it’s not particularly accurate. social insurance systems for injury and illness have significant issues with moral hazard.

For example, before 15 July 1980, an employee injured in a workplace accident in Kentucky received compensations proportional to his or her wage with an upper limit of $131 per week.

On 15 July 1980, this limit was raised to $217 per week. The better paid wage-earners were substantially better compensated for accidents that occurred after that date.

The periods of convalescence of these better-paid workers grew 20 per cent longer. For accidents that occurred before 15 July, these employees had been off work for an average of 4.3 weeks; for accidents after 15 July caused the same employees to stay home for an average of 5.2 weeks.

The average convalescence period for injured workers who were less well paid was unaffected by the rise in the upper limit stayed the same before and after 15 July. It is absurd to suggest that workplace accidents had suddenly become more serious for these better-paid workers and only for them after 15 July 1980.

In the past three decades, the number of people who are on disability benefit has skyrocketed but incidence of disabling health conditions among the working age population is not rising. Autor (2006) found that disability rolls in the USA expanded because:

- congressional reforms to disability screening in 1984 that enabled workers with low mortality disorders such as back pain, arthritis and mental illness to more readily qualify for benefits;

- a rise in the after-tax income replacement rate, which strengthened the incentives for lower-skilled workers to seek benefits; and

- a rapid increase in female labour force participation that expanded the pool of insured workers.

Autor found that the aging of the baby boom generation has contributed little to the growth of disability benefit numbers to date.

David Autor and Mark Duggan (2003) found that low-skills and a poor education is predictor of disability: in the USA in 2004, nearly one in five male high school dropouts between ages 55 and 64 were in the disability program; that was more than double that of high school graduates of the same age and more than five times higher than the 3.7 % of college graduates of that age who collect disability. Unemployment is another driver of disability.

The only major success in reducing beneficiary numbers anywhere has been time limits in the USA in 1996. Time limits on welfare for single parents reduced caseloads by two thirds, 90% in some states.

The subsequent declines in welfare participation rates and gains in employment were largest among the single mothers previously thought to be most disadvantaged: young (ages 18-29), mothers with children aged under seven, high school drop-outs, and black and Hispanic mothers. These low-skilled single mothers were thought to face the greatest barriers to employment. Blank (2002) found that

nobody of any political persuasion predicted or would have believed possible the magnitude of change that occurred in the behaviour of low-income single-parent families.

Rebecca Blank is the field leader on the economics of welfare reform and got as high as Acting Secretary of the Department of Commerce for Obama.

Employment are never married mothers increased by 50% after the US reforms: employment a single mothers with less than a high school education increased by two thirds: employment of single mothers aged of 18 in 24 approximately doubled.

With the enactment of welfare reform in 1996, black child poverty fell by more than a quarter to 30% in 2001. Over a six-year period after welfare reform, 1.2 million black children were lifted out of poverty. In 2001, despite a recession, the poverty rate for black children was at the lowest point in national history.

This great success of US welfare reforms was that after decades of no progress, poverty among single mothers and among black children declined dramatically.

The best solution to poverty is to move people into a job. Simon Chapple is also quite clear in his mid-year book with Jonathan Boston that a sole parent in full-time work, and a two parent family with one earner with one full-time and one part-time worker, even at low wages, will earn enough to lift their children above most poverty thresholds. Welfare benefits trap children in poverty.

The best available analysis, the most credible analysis, the most independent analysis in New Zealand or anywhere else in the world that having a job and marrying the father of your child is the secret to the leaving poverty is recently by the Living Wage movement in New Zealand.

According to the calculations of the Living Wage movement, earning only $18.80 per hour with a second earner working only 20 hours affords their two children, including a teenager, Sky TV, pets, international travel, video games and 10 hours childcare.

This analysis of the Living Wage movement shows that finishing school so your job pays something reasonable and marrying the father of your child affords a comfortable family life.

Blogs so far:

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

Is welfare dependence optimal for whom – part 6: mandatory work requirements and labour supply

14 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, welfare reform Tags: 1996 federal welfare reforms, Labour leisure trade-off, labour supply, mandatory work requirements, welfare reform

A mechanism for reducing welfare programme entries while increasing welfare exits is work requirements. These minimum hours can be spent working part time, in study and training, work preparation and job search assistance or volunteering.

A work requirement is a screening device removes any advantage of moving on to welfare in terms of more leisure time. U.S. welfare reform side-stepped the problem of programme entry with lifetime time limits on eligibility and work requirements making entry unrewarding. A lifetime time limit on eligibility also reduces inflow in to welfare receipt because workers have an incentive to bank their eligibility to hard time arise. Different work tests and abatement regimes that vary with circumstances on length of time on the benefit also increase exits without increasing entry.

Most work requirement schemes have waivers for those unable to work. Work requirements make welfare receipt less attractive and more hassle while not making welfare receipt any more or any less financially rewarding to those in work.

The gap between working and welfare receipt is larger because of the work requirements make the benefit less pleasant but no additional cash payments are made to encourage welfare programme entry.

Most welfare systems experiment with policy options to separate those who can work from the truly needy. Changes in financial incentives arising from abatement regimes, benefit levels and benefit durations are welfare reform workhorses. The clear-cut labour supply effects of work requirements are a useful contrast to the ambiguity of labour supply changes when benefit levels and abatement regimes change.

Figure 1 illustrates work requirements by introducing a minimum working hours requirement, which eliminates part of the budget constraint before the minimum hours. Work requirements combine a negative tied transfer – an obligation to work – with cash to induce those with a higher ability to work to self-select and opt out of the welfare system entirely.

Figure 1: The labour supply effects of mandatory work requirements as a condition of welfare benefit receipt

Arrows 1, 2 and 3 in Figure 1 represent possible labour supply responses to work requirements which lead to an increase in the hours worked by different types of workers, some moving to working part-time and others not working at all.

Arrow 1 shows some beneficiaries who are marginal workers increasing their hours from zero to the minimum. Other marginal workers will work more but no longer work enough hours to qualify for a benefit as shown by arrow 2.

This increase in labour supply, as shown by arrows 1 and 2 in Figure 1, is to be expected because a work requirement eliminates welfare benefits altogether over a certain range.

Welfare payments reduce the supply of labour unambiguously so reducing the generosity of welfare reduces the disincentives to supply labour.

A work requirement also reduces entry into and increases exit from the welfare system by more persistent workers as shown by arrow 3 in Figure 1.

This welfare exit effect and entry deterrence arises from the relative non-financial rewards of working and not working have changed in favour of staying in full-time and semi-work for persistent workers temporarily on a welfare benefit.

Persistent workers gain from anticipating the onerous nature of work requirements and searching more intensively for jobs which are more stable and enduring.

These job seekers may reduce their asking wage to win a lower paid but steadier job. Seasonal and temporary jobs will be less attractive if there are work requirements.

The incentive to cycle between the benefit and part-time and full-time work including seasonal and temporary jobs are reduce because work requirements make welfare receipt more onerous.

Those job seekers with fewer outside of the workforce obligations such as young children are the most likely to move to (stable) full-time work because of work requirements.

Those with more extensive outside commitments such as pre-schoolers work the minimum hours or make other arrangements because they now fail to qualify for welfare.

A work requirement unambiguously increases net labour supply and reduces the number of people relying on the welfare system now and into the future.

In contrast to abatement regime reforms, no one enters the welfare system as a new benefit claimant as the result of introducing work requirements.

The number of people working increase and some leave welfare rather than comply with the work programmes. Work requirements make welfare receipt unambiguously less attractive and will close the gap between earning full-time wages and the net rewards of not working or part-time work and partial benefit receipt.

The 60 per cent reduction in welfare caseloads that followed the 1996 federal welfare reform in the USA that introduced work requirement and time limits on a national basis.

The subsequent declines in welfare participation rates and gains in employment were largest among the single mothers previously thought to be most disadvantaged: young (ages 18-29), mothers with children aged under seven, high school drop-outs, and black and Hispanic mothers. These low-skilled single mothers who were thought to face the greatest barriers to employment. Blank (2002) found that:

At the same time as major changes in program structure occurred during the 1990s, there were also stunning changes in behaviour. Strong adjectives are appropriate to describe these behavioural changes.

Nobody of any political persuasion-predicted or would have believed possible the magnitude of change that occurred in the behaviour of low-income single-parent families over this decade.

The blogs so far

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

Policy bubbles alert: can more money reduce child poverty?

12 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, welfare reform Tags: capitalism and prosperity, poverty and inequality, Susan Mayer, The Great, the withering away of the proletariat, welfare reform

Susan Mayer in her book What Money Can’t Buy found very little evidence to support the widely held belief that parental income has a significant effect on children’s life outcomes. Mayer:

Susan Mayer in her book What Money Can’t Buy found very little evidence to support the widely held belief that parental income has a significant effect on children’s life outcomes. Mayer:

- Challenged the assumption that poverty directly causes poor health, behavioural problems, and a host of other problems for children;

- Also stated that there was no correlation but a coincidence with a missing third factor, which was jobs; and

- Found that household conditions are highly responsive to income but how it is spent is what matters more.

These findings were Susan Mayer are of profound importance because far too many people believe the solution to child poverty is to give the poor more money. What could be simpler.

Capitalism have been giving the poor more money for centuries now. This great enrichment dwarfs anything that redistribution and egalitarian politics and the welfare state has done in the 20th century.

Mayer said that her findings do not endorse massive cuts in welfare:

My results do not show that we can cut income support programs with impunity…

Indeed, they suggest that income support programs have been relatively successful in maintaining the material living standard of many poor children.

Mayer found that non-monetary factors play a bigger role than previously thought in determining how children overcome disadvantage as she explains.

Parent-child interactions appear to be important for children’s success, but the study shows little evidence that a parent’s income has a large influence on parenting practices.

Mayer said that if money alone were responsible for overcoming such problems as unwed pregnancy, low educational achievement and male idleness, states with higher welfare benefits could expect to see reductions in these problems. In reality,

once we control all relevant state characteristics, the apparent effect of increasing Aid to Families with Dependent Children benefits is very small

Mayer is of the view that many of the activities that improve children’s outcomes are more related to parenting choices than to income:

They mainly reflect parents’ tastes and values.

Books appear to benefit children because parents who buy a lot of books are likely to read to their children.

Parents who do not buy books for their children are probably not likely to read to them even if the books are free, and parents who do not take their children on outings may be less likely to spend time with them in other ways.

Among her findings, which have largely survive the test of time, are:

- Higher parental income has little impact on reading and mathematics test scores.

- Higher income increases the number of years children attend school by only one-fifth of a year.

- Higher income does not reduce the amount of time sons are idle as young adults.

- Higher income reduces the probability of daughters growing up to be single mothers by 8 to 20 percent.

Mayer found that as parents have more money to spend, they usually spend the extra money on food, especially food eaten in restaurants; larger homes; and on more automobiles.

As a result, children are likely to be better housed and better fed, but not necessarily better educated or better prepared for high-income jobs. This is her key conclusion about what money can and cannot buy:

If we are asking specifically about the relationship between parental income and children’s outcomes, a fairly clear answer is emerging: parental income itself has a modest effect on children’s outcomes and this effect is not necessarily greater for children from poor families compared to children from rich families.

Mayer’s analysis in many ways reflects her own life story. She divorced in the mid-1970s and had so many money troubles that she had trouble paying the rent.

She remarried in the early 1980s and had a second child. This second child at a comfortable middle-class upbringing. The mother went on to complete a Ph.D. and ended up as head of the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago.

Mayer noticed that both of her children turned out pretty much the same despite the older child was raised in poor circumstances. The common factor to this success was they had the same mother.

Is welfare dependence optimal for whom – part 5: higher abatement rates and labour supply

12 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: labour economics, welfare reform

Paradoxically, the main way of using financial incentives to increase net labour supply of beneficiaries and move more off the benefit is to toughen the benefit abatement regime.

This increase in the abatement rates on welfare benefits for earned income moves more off the benefit and moves more into full-time employment but still with an ambiguous effect on part-time employment. Some may prefer the benefit over their current part-time job.

The notion that tinkering with financial incentives will not have large effects on labour supply and benefit numbers is not new. Increase in the generosity of welfare benefits with increase the number of applicants.

Tinkering with the details of abatement rates and thresholds has ambiguous labour supply effects because exits from welfare are still offset by new entry onto welfare. The netting the labour supply changes of these diverse groups often leads to welfare reform leading to positive but small change in labour supply. Quantitatively, an old finding is the remarkable lack of effects of financial incentives on welfare participation (Moffitt 1992, 2002).

Under a move up to a 100 per cent benefit abatement rate as shown in Figure 1; arrow 1 in Figure 1 shows that some who were working part-time will now find not working at all to be the more attractive option. The new 100 per cent benefit abatement rate reduces their take-home pay but they enjoy more leisure time.

Figure 1: the labour supply effects of an increase to a 100 per cent benefit abatement rate

Arrow 2 in Figure 1 shows that some part-time workers increase their working hours because working a little more mitigates the reduction in their take-home pay and allow some leisure time.

Arrow 3 in Figure 1 shows that some part-timers return to full-time working hours because of the revised leisure-labour trade off that now makes a somewhat higher take-home pay worthwhile despite reduced leisure time.

Whether net labour supply increases or falls after a rise in the benefit abatement rate to 100 per cent depends on the relative numbers of workers at different points on the budget constraint that are working full-time, not working, and working part-time and the magnitudes of their responses.

Some will stay as they are working either full-time, not working or working part-time. Others supply more labour. Working more hours may increase their take-home pay depending on how productivity they are.

Some part-timers will move to full-time in low paid jobs with take-home pay because of the loss of benefit income, they will enjoy less leisure time and there can be additional costs such as child care.

More productive workers in better paid jobs will take home more in pay by moving to full-time but will enjoy less leisure time. Some workers that were previously working part-time stop working and rely in welfare benefits.

If reduced welfare dependence is the objective, high abatement rates and low abatement thresholds are the path to follow. With a move to 100 per cent abatement of benefits, some leave the welfare system but no one joins it because of the higher abatement rate.

Less generous abatement will see some who claim the benefit while working part-time move to a lower take-home pay. Some will be on a higher take-home pay working full-time. The net labour supply effect is ambiguous because some leave work altogether while others work more hours.

The net labour supply depends on the relative numbers at different points on the budget constraint working full-time, not working, or working part-time and the magnitudes of their respective individual labour supply responses. Some people will stay as they are working full-time, not working or working part-time.

No one who previously did not work is worse off under the benefit abatement rate increase to 100 per cent because they are unaffected by abatement. Some who were working part-time and previously claiming the benefit take-home less but enjoy more leisure as shown by arrow 2 in Figure 1. The remaining part-time workers now take-home more pay but enjoy less leisure because they are working more hours and even full-time as shown by arrow 3 in Figure 1.

The blogs so far

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

Is welfare dependence optimal for whom – part 4: In-work tax credits and labour supply

10 Dec 2014 3 Comments

in labour economics, labour supply, public economics, welfare reform Tags: Labour leisure trade-off, welfare dependency, welfare reform

In-work tax credits were introduced in many countries including New Zealand to encourage movement into employment by breadwinners. By linking a large payment with full-time and semi-full-time work, the rewards for working are increased for single parents and families. These in work tax credits combined child tax credit with an in work tax credit for the sole mother or couple.

These in-work benefits can phase-in when a minimum income level is reach such as with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the USA, or a paid in full when a minimum number of hours are worked. The Working for Families in-work tax credit in New Zealand and the UK family tax credit are two examples where there is a large cash payment with no phasing-in:

- Working for Families in New Zealand is paid if 30 hours are worked by New Zealand families or 20 hours are worked by sole parents; and

- The British family tax credit was paid if 16 hours are worked, initially 24 hours per week.

Figure 1 shows the impact of the introduction of an in-work tax credit paid in full to families and sole parents if a minimum number of hours per week are worked by a family or sole parent. There is no phase-in region such as with the earned income tax credit (EITC) in the USA.

Figure 1: In work tax credits and labour supply

The in-work tax credit phases-out after once the family’s income increases past an income threshold. This income threshold is usually linked to the number of children as well.

An in-work family tax credit linked to a high number of minimum number of hours worked provides an incentive for those not in work to increase their hours worked by a large amount and leave welfare, as is shown by arrow 1 in Figure 1.

For those already work, the income and substitution effect cut against each other and their net effect depend on the number of hours currently worked.

- Those working a low number of hours, hours less per week than the minimum to qualify for the in-work tax-credit have an incentive to increase their hours to the minimum to qualify and leave welfare is shown by arrow 2 in Figure 1.

- Arrows 3 and 4 in Figure 1 both represent reduction in hours worked.

- Some workers can take-home more pay and work fewer hours per week or per year as shown by arrow 3.

- Other high working hours worker can enjoy more leisure time at the expense of a slightly reduced take-home pay as shown by arrow 4.

The net labour supply effects of an in-work tax credit are therefore ambiguous because of these multiplicity of labour supply effects with some people working more another’s work in letters.

There will also be a bunching of hours worked at around the eligibility point for paying the in-work tax credit. The eligibility point is usually grouped around working a minimum of three or four days per week part or full-time that sum to 30 hours for families and 20 hours for sole parents.

Workers working less that the weekly working hour minimums will increase to the minimum to qualify for the family tax credit. Workers working more than the minimum required to qualify for the family tax credit might cut back to the working hours minimum because of the superior labour leisure trade-off. The number of people on welfare will fall because workers leave part and full benefit dependence to qualify for the in-work tax credit.

Whether labour supply on net actually increases or decreases depends on the relative numbers of individuals at different points on the budget constraint working full-time, not working and working part-time and on the magnitudes of their responses. Some will stay as they are working full-time, not working and working part-time.

To summarise, the static labour–leisure trade-off model of labour supply suggests that increases in either benefit abatement thresholds or a reduction in benefit abatement rates will increase the numbers entering the benefit and see none leave. No one will leave.

A hours worked per week based in-work tax credit will move people who are not working and working a low number of hours to work and into a higher number of work hours respectively, with bunching around the eligibility point. An in-work tax credit will also cause some to cut back their hours so the net labour supply effect is ambiguous.

The net fiscal cost of an in-work tax credit depends on the phase-in and phased out particulars of the tax credit programme and the increase in paid employment and the number of taxpaying workers as a result of the in-work tax credit. The Working for Families tax credits in New Zealand and the United Kingdom are famous for clustering of labour supply around the eligibility point for the in work tax credit.

For example, in the UK, a lot of people used to work exactly 24 hours week. When the eligibility point was reduced to 16 per week, a new word had to be invented. This new word was mini-jobs to describe the large number of part-time workers in the UK who cut-back to exactly 16 hours per week. The family tax credit for workers is twice as generous in the UK as in New Zealand.

The blogs so far

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

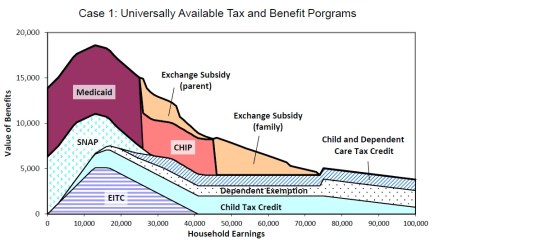

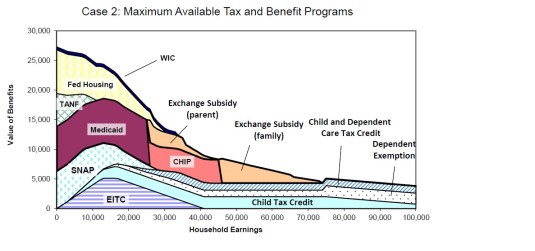

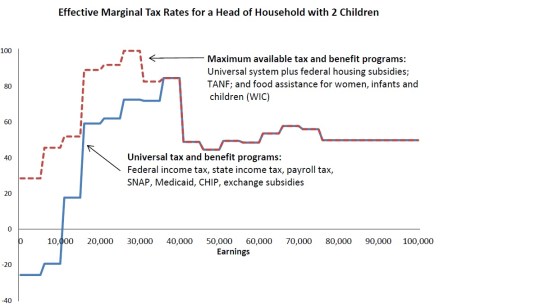

The shape of the welfare state in the USA

08 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in fiscal policy, income redistribution, labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA, public economics, welfare reform Tags: effective marginal tax rates, Obama care, poverty traps, welfare reform

One in five Americans on Medicaid; this image does not include those on Medicare –those over 65 who get their healthcare paid by the government.

Is welfare dependence optimal for whom – part 3: abatement free income thresholds and labour supply

08 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, welfare reform Tags: Labour leisure trade-off, welfare reform

Another welfare reform is a modest income threshold below which benefits are not abated. This is low for unemployment and sickness beneficiaries and higher for domestic purposes and invalid beneficiaries.

The idea behind abatement-free income thresholds is to not penalise part-time work among sole mothers and encourage the unemployed and sick to return to full-time work.

The Figure 1 shows that an increase in the benefit abatement threshold has similar ambiguous net labour supply effects to a lowering of welfare benefit abatement rates.

Figure 1: Impact of abatement thresholds on labour supply

- Arrow 1 in figure 1 shows that some who were not currently working will now find working part-time a more attractive option because of the introduction of a benefit abatement-free threshold. Their take-home pay is higher although they enjoy less leisure time.

- Arrow 2 in figure 1 shows that some part-time workers will reduce their working hours because working less and claiming the benefit clearly increases both their take-home pay and allow for more leisure time.

- Arrow 3 in figure 1 shows that workers who work a relative high number of hours per week for a relative low wage will reduce from full-time to part-time working hours because of a revised leisure-labour trade off now makes a somewhat lower take-home pay worthwhile because of increased leisure time.

- No welfare recipients leave the welfare system but some join it because of the introduction or increase in the abatement-free income threshold.

The net labour supply effects of a higher benefit abatement-free threshold are ambiguous because the reduced hours of those already in work offsets the labour force participation of those previously not in work.

Whether net labour supply increases or decreases depends on the relative numbers of individuals at different points on the budget constraint working full-time, not working and working part-time and on the magnitudes of their responses. Some will stay as they were either working full-time, not working or working part-time.

The objective of reducing welfare dependency by encouraging part-time work by those not working has important unintended adverse consequences for the labour supply and welfare dependency of those currently working part-time and full-time on low wages.

A common result of welfare reforms that increase abatement thresholds or reduce abatement rates is that no welfare recipients leave the welfare system but some join it. Welfare dependency is not reduced by financial incentives that increase the generosity and the availability of welfare benefits.

The labour supply effects of welfare reforms that increase benefit abatement thresholds or reduce benefit abatement rates are ambiguous because the reduced working hours of existing workers offsets the hours worked by those not employed prior to the reform. A further complexity is that encouraging part-time work channels beneficiaries into low paid jobs that offer little training and other human capital benefits.

In summary, an increase in the benefit abatement-free income thresholds for welfare recipients has the following effects:

- not all welfare recipients will respond to a higher abatement-free income threshold by supplying more labour;

- those welfare recipients who do respond to a higher abatement-free income are better-off and supply more labour and take-home more pay;

- the increase in labour supply is in part-time work by beneficiaries earning income up to the higher abatement-free income threshold;

- No welfare recipient leaves the welfare system – those welfare recipients who respond to this welfare reform continue to collect their full welfare benefit and work a few more hours each week.

While reforming the welfare system is intended to change the labour market behaviour of welfare recipients, it also has unintended consequences on individuals who are not collecting welfare benefits.

An increase in the exemption level for earned income affects the labour market behaviour of someone who is not receiving welfare benefits has the following effects:

- prior to the increase in the abatement-free threshold, the individual is best off by working part-time or full-time and not collecting welfare or even being eligible to collect welfare benefits; and

- after an increase in the benefit abatement-free income threshold, a worker is better-off by supplying less labour and collecting a full welfare benefit, which raises their total income.

Permitting welfare recipients to keep larger amounts of income without losing any of their welfare benefits will attract more workers into the welfare system. Some workers will find that they are better-off by joining the welfare system and switch from full-time work to being a welfare recipient who works part-time (up to the new higher exemption level). The cost of the welfare programme increases, there are more welfare recipients, and no welfare recipient loses any benefits.

All welfare recipients who increase their labour supply up to the new higher exemption level (and lower abatement rates) and all workers who switch to the welfare system will be better-off.

The effect of the quantity of labour supplied is ambiguous: some old welfare recipients will increase their labour supply up to the new higher abatement-free threshold (probably by a relatively small amount) but new welfare recipients will decrease their labour supply (probably by a relatively large amount) as they move from full-time work to part-time work on welfare.

The overall effect of changes in benefit abatement regimes depends on the number of old and new welfare recipients and the size of the labour supply change for each.

- The quality of labour supplied will deteriorate as some full-time workers switch to welfare and work part-time; part-time workers generally have less attachment to the labour force and tend to invest less in human capital to up-grade their labour market skills.

- High-productivity workers are working fewer hours while lower-productivity workers work more hours.

If the objective is to reduce the number of people on welfare by moving some welfare recipients (those who are able to work) into work, increasing abatement free income thresholds or lowering abatement rates are not the solution. Both options increase the number of people on welfare.

A reduction in the amount of welfare benefits will reduce the number of people on welfare, reduce the cost of the welfare programme, increase the supply of labour, increase the number of full-time workers relative to part-time workers but make all current welfare recipients worse-off and risks providing inadequate income support to those who are unemployable.

The blogs so far

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

Is welfare dependence optimal for whom – part 2: the labour supply effects of welfare benefit abatement rate changes

06 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, welfare reform Tags: benefit dependency, Labour leisure trade-off, welfare reform

Figure 1 shows that the introduction of a welfare benefit has both income and substitution effects. The welfare benefit abates at rate t so the take-home pay of workers is less than the full wage until the benefit cut out point shown by the arrow in Figure 1. After this cut-out point, no benefits are payable and the work receives a full wage of w times the hours worked.

Figure 1: the labour supply effects of the introduction of a welfare benefit

The income effect increases the consumption of all goods including leisure. The substitution effect increases the attractiveness of not-working relative to work because prior to the cut-out point, take-home pay is less.

· Some workers will choose to not work at all as indicated by arrow 1 in figure 1 because this makes them better off. They have more leisure time and more income.

· Other workers working at a relative low wage will work less hours than before as indicated by arrow 2 in Figure 1 because of the revised rewards of working. Working fewer hours for slightly less is a better labour-leisure trade-off for them. They earn less, but have more leisure time.

Figure 1 illustrates several of the ambiguities of welfare reform. A welfare benefit induces some workers to work fewer hours and others to stop working altogether. In addition, the abatement rate of less than 100 per cent increases the region in which workers working full-time or semi-full-time might find working less hours attractive. Some workers move from full-time work to part-time work on lower income but with more leisure time.

If the benefit abatement rate was 100 per cent, there is a larger gap between working full-time and not working at all. This large take-home pay gap makes jumps from not working to full-time work much more rewarding.

Several jurisdictions increased benefit abatement rates to 100 per cent to make full-time work more rewarding and part-time work less rewarding. Higher benefit abatement rates on earned income of welfare beneficiaries may actually increase net labour supply because fewer workers enter the benefit, more leave for full-time jobs, but fewer work part-time.

These intended and unintended consequences of welfare reform for abatement rate reforms are illustrated further in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Benefit abatement rate reductions and labour supply

Benefit abatement rates are reduced in Figure 2, which increases the cut-out point at which workers cease to be eligible for any welfare benefits.

· Arrow 1 shows the decision of those currently not working to start working part-time, which is a common motive for and the desired outcome behind reduced benefit abatement rates. These beneficiaries are working but are taking-home a higher income. Their labour leisure trade-off now favours more work and less leisure.

· Arrow 2 shows those currently working part-time reducing their hours because this clearly increases both their take-home pay and their leisure time.

· Arrow 3 shows the full-time workers working at a relative low wage have an incentive to reduce to part-time because this is a better labour-leisure trade-off for them. Their take-home pay is less, but they enjoy more leisure time.

The net labour supply effects of lower abatement rates are ambiguous because the reduced hours of those who are already in work offsets the labour force participation of those previously not working.

A key point to remember from this reduction in welfare abatement rates is no welfare recipients leaves the welfare system but some join the welfare rolls because of the reduction in the benefit abatement rate.

Whether labour supply on net actually increases or decreases depends on the relative numbers of individuals at different points on the budget constraint working full-time, not working and working part-time and on the magnitudes of their responses.

Some will stay as they are working full-time, not working and working part-time. Others will reduce their hours of work. The dictates of team production and co-ordinated working times may prevent this happening immediately. At the next job changes, those currently working full and part-time can take full advantage of lower benefits abatement rates as shown in Figure 2.

The objective of reducing welfare dependency and poverty by encouraging part-time work with lower benefit abatement rates has unintended consequences.

People focus on those who start working part-time as a conduit to eventual full-time work and self-sufficiency if welfare abatement rates are lowered to make part-time work more attractive.

What is forgotten is those who are currently working full-time, or part-time, who because of the increase in income from part-time work plus continued for partial benefit receipt find that part-time welfare dependency is optimal for them. They drop out of full-time work.

An additional reason for this entry of new people onto the welfare rolls is that welfare benefits come with a range of second tier benefits. In addition to housing supplements to pay the rent, there are special grants that can be applied for to pay for unexpected expenses such as medical and dental work or damaged around the house.

As alluded to previously, one of the welfare reforms introduced in the United States in the early 1980s was to increase the welfare abatement rate on earned income to 100% from 67% which it applied since the 1960s. This increase in welfare benefit abatement rates to 100% on earned income increased the gap between welfare dependency and working full time. The idea was to make full-time work a more attractive option relative to welfare benefit receipt.

The blogs so far

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3329592/DI_Chartbook_Section_Three-04.0.png)

Recent Comments