The biggest drop was in a company that sold its sugar interests in 2009 so that was a rather within the day affair once traders realised their error.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

18 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, financial economics, health economics Tags: British economy, libertarian paternalism, meddlesome preferences, nanny state, sugar tax

The biggest drop was in a company that sold its sugar interests in 2009 so that was a rather within the day affair once traders realised their error.

16 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

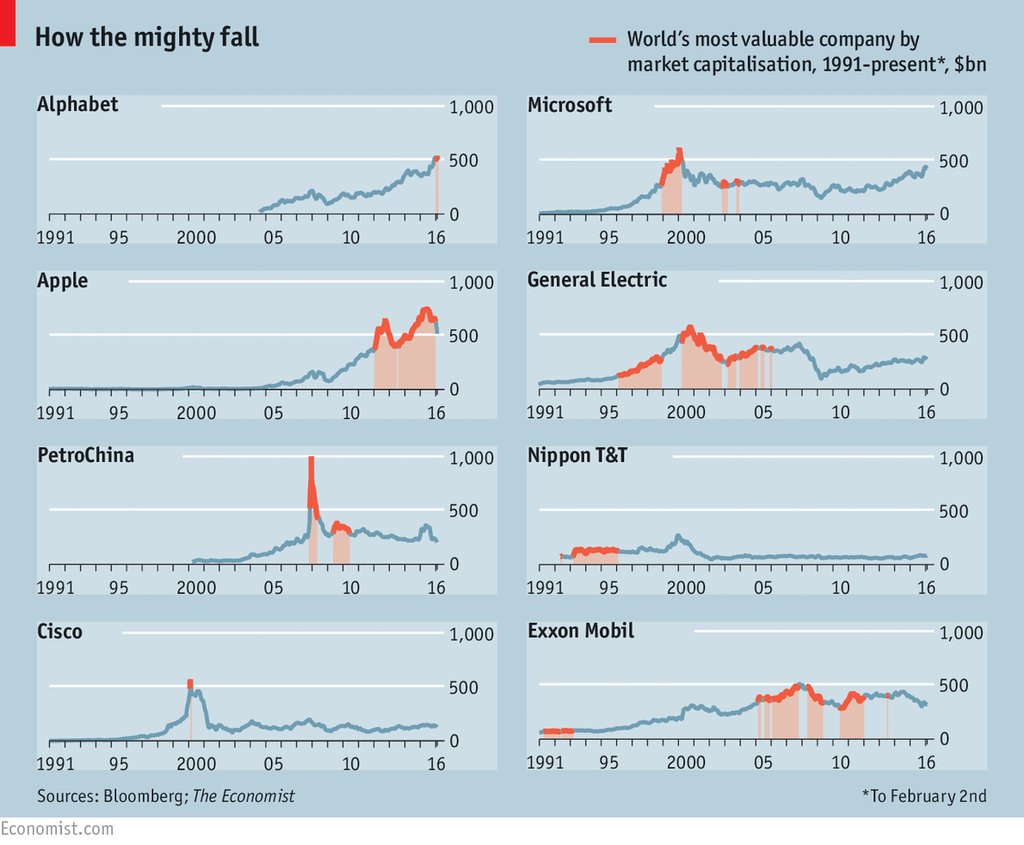

in economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics Tags: creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness

.

15 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in financial economics, industrial organisation, law and economics, monetary economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: competition law, competition policy, economics of banking, state owned enterprises

27 Feb 2016 1 Comment

in environmental economics, financial economics, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, public economics, survivor principle Tags: agricultural economics, privatisation, state owned enterprises

As cash cows go, Landcorp has had $2.25 million more in capital injections from taxpayers than it returned to them in dividends since 2007.

Source: data released by the New Zealand Treasury under the Official Information Act.

Those $1.5 billion in assets in Landcorp do not appear to be worth a cent in net cash to the long-suffering taxpayer.

Source: data released by the New Zealand Treasury under the Official Information Act.

Landcorp is a state-owned enterprise of the New Zealand government. Its core business is pastoral farming including dairy, sheep, beef and deer. In January 2012, Landcorp managed 137 properties carrying 1.5 million stock units on 376,156 hectares of land.

24 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in development economics, economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics, growth miracles, industrial organisation, rentseeking, survivor principle Tags: billionaires, China, entrepreneurial alertness, Hong Kong, Japan, superstar wages, superstars, Taiwan

Surprisingly few billionaires in any of the 4 countries obtained their wealth through political connections. Founding a company seems to be still the path of great wealth even in Japan these days. Hong Kong is a financial centre so the large number of billionaires in its financial sector is no surprise.

18 Feb 2016 1 Comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics, industrial organisation Tags: billionaires, entrepreneurial alertness, Philippines, superstars, top 1%

A surprisingly large number of Filipino billionaires are in the financial sector.

16 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic history, economics of regulation, entrepreneurship, financial economics, human capital, industrial organisation, labour economics, poverty and inequality, survivor principle Tags: billionaires, British economy, entrepreneurial alertness, superstars, top 1%

Inheriting wealth is not what it used to be in Britain. There are all these upstarts running businesses or working in the City.

06 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of regulation, financial economics, politics - USA

03 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in defence economics, economic history, economics of regulation, energy economics, entrepreneurship, environmental economics, financial economics, global warming Tags: active investing, disinvestment, entrepreneurial alertness, ethical investing, Fossil Fuels, green rentseeking, hedge funds, passive investing, renewable energy, solar power, Vice Fund, wind power

Just as the Vice Fund specialises in investing in tobacco, alcohol, gaming and defence shares, Cool Futures Funds Management is starting-up to specialise in betting against global warming by shorting green stocks:

…instead of renewables being our energy future, they’re betting on the subsidies drying up and the whole industry collapsing; instead of fossil fuels being left in the ground as “stranded assets”.

An example of the nice little earners this hedge fund can come across is anticipating when particular investors will want to disinvest from fossil fuels.

When institutional investors ranging from universities to sovereign investment funds such as the New Zealand Superannuation Fund seek to disinvest from fossil fuels, that will be a good time to buy cheap shares.The

02 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, business cycles, economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics, movies Tags: bank runs, financial crises

About the only time the Hollywood Left oozes with patriotism is when getting stuck into Wall Street. Hollywood must get its revenge for all those times investors did not back their film pitches, trimmed budgets and get the lion’s share of merchandising royalties and syndication profits. As Larry Ribstein explained:

American films have long presented a negative view of business…. it is not business that filmmakers dislike, but rather the control of firms by profit-maximizing capitalists… this dislike stems from filmmakers’ resentment of capitalists’ constraints on their artistic vision.

The Big Short is still a good film despite the left-wing populism, worth going to see. Its limitations in not discussing the monetary policy of The Fed or regulations that encouraged lending to high risk borrowers are justified poetic license and editing.

The film is already 120+ minutes long despite frequent resorts to breaking the fourth wall to explain technical terms, who was what and what they were doing, past and present. The Big Short is a film designed it make money at the box office, not a semester long documentary.

The Big Short is well acted, funny, insightful and still a good story despite the documentary element that was impossible to do without.

The Big Short highlights that its protagonists had skin in the game. They were investing in mortgages or shorting the same in the expectation of a crash. There were no windbags and armchair critics in The Big Short talking gloom and doom on the horizon without investing their own money to profit from their forecasts. That said, the protagonists betting on a sub-prime mortgages crash, bar two of them, were a little bit nutty.

I do not know any of the critics of the economics of the film’s explanation of the sub-prime crisis who suggested how they could fix these gaps in its economics without making the film much, much longer.

These critics fall into the exact same trap that the Big Short was not about. The Big Short was about investors to put their money where their mouth is. The critics of the film should put their script doctoring skills where their mouths are at least of The Big Short.

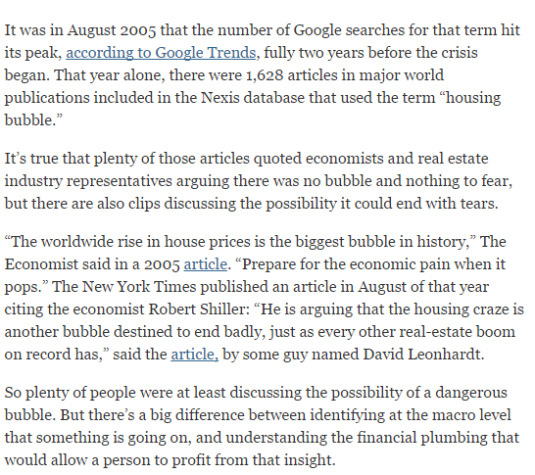

Source: What ‘The Big Short’ Gets Right, and Wrong, About the Housing Bubble – The New York Times.

Getting stuck into the role of the Fed and regulatory mandates on the banks regarding their level of sub-prime mortgages is for another film. Plenty of people warned of dark days ahead. An essay anyone can read with profit is Ross Levine’s “An Autopsy of the U.S. Financial System: Accident, Suicide, or Negligent Homicide?“

Other films, correctly documentaries, place the blame for the sub-prime crisis and the Great Recession directly on the Fed:

The financial mess we’re still climbing out of can be laid directly at the feet of the Fed, whose misguided advocacy, under Greenspan, of a borrow-and-spend economy rather than a focus on savings and investment has created a situation where, as the title implies, money is disconnected from any underlying value.

There are plenty of points that could be added to the economics of The Big Short if it was a film of more or less unlimited length:

Krugman and friends like the film because it leaves out any discussion of the main culprit behind the financial crisis, which was not Wall Street “greed” but bad monetary and credit policies from the Federal Reserve and the federal government. The movie barely hints at any exogenous factors behind the boom or bust. (This FEE report by Peter Boettke and Steven Horwitz fills in the missing information.) So the pro-regulation crowd is cheering. Viewers are given no understanding of the real causal factors and hence fill in the missing data with a feeling that banks just love ripping people off. To be sure, if you approach this movie with some knowledge of economics and monetary policy, the rest of the narrative makes sense. Of course Wall Street got it wrong, given Washington’s policies on mortgage lending!

To add to the brew, Edward Prescott points out the Great Recession can be explained through productivity shocks. Specifically, a collapse in investment and in particular investment in intangibles such as intellectual property in 2007 in anticipation of more taxes and more regulation.

The Great Recession had many of the same features of the 1990s technology boom but in reverse. The boom in the 1990s and bust in 2007 were somewhat inexplicable because major sources of volatility were unmeasured, specifically, investment in intangible capital.

V.V. Chari also points out that the extent of the financial crisis was overstated. This is because the typical firm can finance its capital expenditures from retained earnings so it was hard to see how financial market disruptions could directly affect investment.

What Chari disputed was that bank lending to non-financial corporations and individuals has declined sharply, that interbank lending is essentially non-existent; and commercial paper issuance by non-financial corporations declined sharply, and rates have risen to unprecedented levels.

John Taylor argues that we should consider macroeconomic performance since the 1960: There was a move toward more discretionary policies in the 1960s and 1970s; A move to more rules-based policies in the 1980s and 1990s; and back again toward discretion in recent years.

These policy swings are correlated with economic performance—unemployment, inflation, economic and financial stability, the frequency and depths of recessions, the length and strength of recoveries. Less predictable, more interventionist, and more fine-tuning type macroeconomic policies have caused, deepened and prolonged the current recession. Robert Hetzel puts it this way:

The alternative explanation offered here for the intensification of the recession emphasizes propagation of the original real shocks through contractionary monetary policy. The intensification of the recession followed the pattern of recessions in the stop-go period of the late 1960s and 1970s, in which the Fed introduced cyclical inertia in the funds relative to changes in economic activity.

Finn Kydland considers fiscal policy to be at the heart of the slow recovery. Instead of restructuring and investing more prudently, Western countries faced with budget shortfalls will seek to increase taxes:

Now imagine trying to incorporate all the above points into a film and keeping it at its current two-hour length?

28 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of bureaucracy, financial economics, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, public economics

Today the Treasury advised that it no longer calculates an annual rate of return on the portfolio of state owned enterprises as a whole. It no longer publishes an annual portfolio report (APR).

Source: Treasury response to Official Information Act request by Jim Rose, 14 January 2016.

The Treasury regards the crown portfolio report which contains performance indicators on the state owned enterprises portfolio as a whole as too resource intensive.

The Treasury prefers to be more forward-looking in their reporting on a quarterly basis to the Minister of Finance. Unfortunately, the Treasury refused to my requests for access to this forward-looking reporting to the Minister of Finance on commercial-in-confidence grounds.

The forward-looking approach to state-owned enterprise performance is now only by the Treasury and the Minister of Finance. No one else has access to this financial performance information.

It is no longer possible to say using a figure calculated by the Treasury whether the portfolio of state owned enterprises as a whole are a good return to the taxpayer or not. Individual annual reports of the state owned enterprises can be reviewed but the portfolio wide rate of return is no longer available from the Treasury with the associated credibility of the same.

A common argument against state ownership is that as a whole government ownership is a bad investment. Specifically, the portfolio of state owned enterprises struggle to pay a return in excess of the long-term bond rate.

A common argument for continued state ownership is the loss of the dividends from privatisation. The vulgar argument such as by the New Zealand Labor Party and New Zealand Greens is if a state owned enterprise is privatised either partially or fully, the taxpayers no longer receive dividends. The fact that the sale price reflects the present value of future dividends is simply ignored.

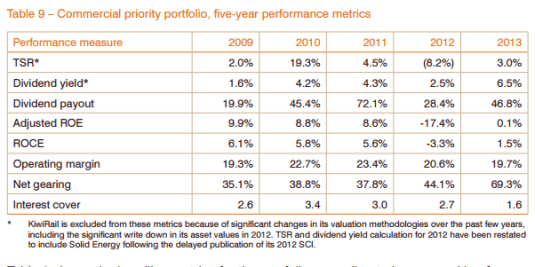

Source: Treasury, Crown Portfolio Report 2013.

The sophisticated argument is the assets are under-priced such as for political reasons. Failed privatisations are indeed the best case against state ownership because governments cannot even sell an asset with such any degree of competence.

Governments are so bad as business owners and so incapable of running a commercial process free of politics that governments cannot even sell a state-owned enterprise for a good price under the full glare of the media and public.

Source: Treasury, Crown Portfolio Report 2013.

A reply to the loss of dividends argument is the dividends from the portfolio as a whole do not repay the government debt incurred to fund capital infusions into state-owned enterprises both when initially established and through time. In that case, it is better to leave your money in the bank than in the state of enterprise.

John Quiggin often criticises privatisation on the grounds that state owned enterprises can invest at a cheaper rate because they are financed at the long-term bond rate:

In general, even after allowing for default risk, governments can borrow more cheaply than private firms. This cost saving may or may not outweigh the operational efficiency gains usually associated with private ownership.

It is not possible to scrutinise that argument without an annual rate of return on the portfolio of state owned enterprises as a whole to see if it is true at first pass at least. As the Treasury no longer calculates a rate of return on the portfolio and taxpayers’ equity, that debate comes to something of a crashing halt in New Zealand.

If these state owned enterprises were privately owned and listed on the share market, investors would just look at trends in share prices for daily measure of expected future profitability.

John Quiggin made the best simple summary of the case for privatisation which was the selling the dogs in the portfolio:

The fiscal case for privatisation must be assessed on a case by case basis. It will always be true for example that if a public enterprise is operating at a loss, and can be sold off for a positive price with no strings attached, the government’s fiscal position will benefit from privatisation.

Various early ventures in public ownership, such as the state butcher shops operated in Queensland in the 1920s (apparently a response to concerns about thumbs on scales) met this criterion, and there doesn’t seem to be much interest in repeating this experiment.

Quiggin also made a measured statement of why state ownership should be limited at most to monopolies:

In most sectors of the economy, the higher cost of equity capital is more than offset by the fact that private firms are run more efficiently, and therefore more profitably, than government enterprises.

But enterprises owned by governments are usually capital intensive and often have monopoly power that entails close external regulation, regardless of ownership. In these situations, the scope to increase profitability is limited, and the lower value of the asset to a private owner is reflected in the higher rate of return demanded by equity investors.

Quiggin is wrong about government enterprises have been a lower cost of capital because it contradicts the most fundamental principles of business finance as explained by Sinclair Davidson:

…it is clear that the Grant-Quiggin view violates the Modigliani-Miller theories of corporate finance. The cost of capital is a function of the riskiness of the investment projects and not a function of a firm’s ownership structure.

How the cash flows of a business are divided between owners and creditors does not matter unless that division changes the incentives they have to monitor the performance of the firm and keep it on its toes. Those lower down the pecking order if things go wrong such as owners have much more of an incentive to monitor the success of the business and lift its performance.

Capital structures of firms, the property rights structures of firms, matter precisely because they influence incentives of those with different claims on the cash flows of the firm.

Having to pay debt disciplines managerial slack and ensures that free-cash flows are used to repay debt (or pay dividends) rather than be invested in low quality new ventures. Having to borrow from strangers such as banks ensures regular scrutiny of the soundness and prospects of the company from a fresh set of eyes. Capital structures made up of both debt and equity keeps the firm on its toes.

Unfortunately, in New Zealand it is much more difficult to review the arguments for and against the current size and shape of the state owned enterprise portfolio as for example summarised by John Quiggin:

Technologies and social priorities change over time, with the result that activities suitable for public ownership at one time may be candidates for privatization in another. However, the reverse is equally true. Problems in financial markets or the emergence of new technologies may call for government intervention in activities previously undertaken by private enterprise.

In summary, privatization is valid and important as a policy tool for managing public sector assets effectively, but must be matched by a willingness to undertake new public investment where it is necessary.

As a policy program, the idea of large-scale privatization has had some important successes, but has reached its limits in many cases. Selling income-generating assets is rarely helpful as a way of reducing net debt. The central focus should always be on achieving the right balance between the public and private sectors.

This balancing of public and private ownership is more difficult in New Zealand because portfolio wide rates of return are unavailable unless you calculate them yourself. That must be labour-intensive given the Treasury thought it was too labour-intensive for it to do for itself.

An obvious motive to start a review the extent of state ownership is the portfolio is performing poorly. That warning sign is no longer available because the crown portfolio report is no longer published.

One way to fix an underperforming portfolio is to sell the dogs in the portfolio. One of the first ways owners notice dogs in their portfolio is the portfolio not returning as well as it used too because of the emergence of these dogs so further enquiries are made and explanations sought.

Taxpayers, ministers and parliamentarians are all busy people with little personal stake in the rate of return on the state owned enterprises portfolio.

Taxpayers, ministers and parliamentarians will all first look at the portfolio wide rate of return to see whether more detailed scrutiny of individual investments is required. That quick check against poor value for money and trouble ahead is no longer available on the state owned enterprises portfolio in New Zealand.

22 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture, entrepreneurship, financial economics Tags: creative destruction, legacy media

18 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in Euro crisis, financial economics, fiscal policy

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments