Stigler on economics as a big tent @RusselNorman @NZGreens @GreenpeaceNZ @Mark_J_Perry

21 Sep 2015 1 Comment

The dangerous left-wing bias of economists strikes again

21 Sep 2015 2 Comments

in applied price theory, budget deficits, business cycles, economics of regulation, history of economic thought, occupational choice, politics - USA

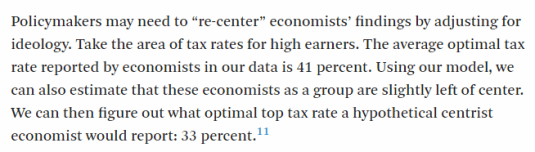

The left-wing bias of economists must be taken into account in public policy-making. Any suggestions to regulate the economy, spend our way out of a recession, increase the top tax rate and so on must be discounted for that well-known but little publicised political bias.

Source: Economists Aren’t As Nonpartisan As We Think | FiveThirtyEight

As is not well-known enough, Cardiff and Klein (2005) used voter registration data to rank disciplines at Californian Ivy League universities by Democrat to Republican ratios. Economics is the most conservative social science, with a Democrat to Republican ratio of a mere 2.8 to 1. This can be contrasted with sociology (44 to 1), political science (6.5 to 1) and anthropology (10.5 to 1). 40% of Americans are Democrats, 32% are independents with the balance Republicans.

Zubin Jelveh, Bruce Kogut, and Suresh Naidu confirmed that bias: that the typical economist is a moderate Democrat. They found a 60–40 liberal conservative bias

Jelveh, Kogut, and Naidu also reminded, as many have before them that economics is the most politically diverse of academic professions. Sociology is a notorious left-wing echo chamber as an example. Their most likely view of Jeremy Corbyn is he is a bit of a Tory. Oddly enough, sociologists are the first to point the finger at economists for political bias.

Jelveh, Kogut, and Naidu correlated political donations of more than $200 in the Federal Elections Commission database with the language used in 18,000 journal articles back to the 1970s.

More interestingly, they correlated political bias with the estimates of quantitative effects such as the top tax rate and its impact on labour supply and investment:

We found a (significant) correlation when we compared the ideologies of authors with the numerical results in their papers. That means that a left-leaning economist is more likely to report numerical results aligned with liberal ideology (and the same is true for right-leaning economists and conservative ideology)… liberals think the fiscal multiplier is high, meaning the government can improve economic growth by increasing spending, while conservatives believe the multiplier is close to zero or negative.

They are not suggesting a rigging of the results. Economists tend to sort into the fields that suit their ideologies:

It’s more likely that these correlations are driven by research areas and the methodologies employed by economists of differing political stripe. Economics involves both methodological and normative judgments, and it is difficult to imagine that any social science could completely erase correlations between these two… macroeconomists and financial economists are more right-leaning on average while labour economists tend to be left-leaning. Economists at business schools, no matter their specialty, lean conservative. Apparently, there is “political sorting” in the academic labour market.

Before you start writing out the indictment that economic policy and the global financial crisis is the product of a vast left-wing conspiracy within the economics profession you should remember the wise words of George Stigler.

Stigler argued that ideas about economic reform needed to wait for a market. He contended that economists exert a minor and scarcely detectable independent influence on the societies in which they live. As is well known, Stigler in the 1970s toasted Milton Friedman at a dinner in his honour by saying:

Milton, if you hadn’t been born, it wouldn’t have made any difference.

Stigler said that if Richard Cobden had spoken only Yiddish, and with a stammer, and Robert Peel had been a narrow, stupid man, England would have still have repealed the Corn Laws in the 1840s. England would still have moved towards free trade in grain as its agricultural classes declined and its manufacturing and commercial classes grew in the 1840s onwards because of the industrial revolution.

As Stigler noted, when their day comes, economists seem to be the leaders of public opinion. But when the views of economists are not so congenial to the current requirements of special interest groups, these economists are left to be the writers of letters to the editor in provincial newspapers. These days, they would run an angry blog.

Greg Mankiw on the zero influence of modern macroeconomics on monetary policy making

17 Sep 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, history of economic thought, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, managerial economics, monetarism, monetary economics, organisational economics Tags: Alan Blinder, Alan Greenspan, credible commitments, Greg Mankiw, modern macroeconomics, monetary policy, neo-Keynesian macroeconomics, new classical macroeconomics, The Fed, timing inconsistency

Two of my brothers studied economics in the early 1970s and then went on to different paths in law and computing respectively. If Greg Mankiw is right, my two older brothers could happily conduct a conversation with a modern central banker. Their 1970s macroeconomics, albeit batting for memory, would be enough for them to hold their own.

Source: AEAweb: JEP (20,4) p. 29 – The Macroeconomist as Scientist and Engineer – Greg Mankiw (2006).

I would spend my time arguing with a central banker that Milton Friedman may be right and central banks should be replaced with a computer. The success of inflation targeting is forcing me to think more deeply about that position. In particular the rise of pension fund socialism means that most voters are very adverse to inflation because of their retirement savings and that is before you consider housing costs are much largest proportions of household budgets these days.

@comcom Commerce Commission understands neither creative destruction nor the scourge of lower prices

24 Aug 2015 2 Comments

in applied price theory, economic history, economics of bureaucracy, history of economic thought, industrial organisation, Joseph Schumpeter, Public Choice, rentseeking, Ronald Coase, survivor principle Tags: antitrust law, competition as a discovery procedure, competition law, competition law enforcement, creative destruction, Harold Demsetz, special interests, The meaning of competition

In its 2014 Consumer Issues report, released under the Official Information Act, the New Zealand Commerce Commission said:

We are seeing signs that NFC transaction systems are replacing the current eftpos payment system with its lower fee structure.

This could result in a transaction fee structure monopoly, and increased charges to consumers as traders pass on their increased transaction costs through surcharges or increased prices.

The Commerce Commission seems rather concerned that one form of supply will be displaced by another at a lower price. This is the scourge of lower prices – a major preoccupation of competition authorities. They are yet to accept that lower prices should be always lawful under competition law.

The distribution of firm sizes reflects the rise and fall of firms in a competitive struggle to survive with competition between firms of different sizes sifting out the more efficient firm sizes (Stigler 1958, 1987; Demsetz 1973, 1976; Peltzman 1977; Jovanovic 1982; Jovanovic and MacDonald 1994b). Business vitality and capacity for growth and innovation are only weakly related to cost conditions and often depends on many factors that are subtle and difficult to observe (Stigler 1958, 1987).

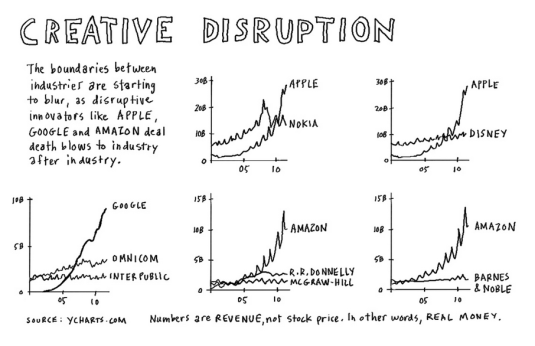

The New Zealand Commerce Commission, the competition law enforcement authority, seems to have an infuriatingly simple and out-dated understanding of the meaning of competition. Joseph Schumpeter and Ronald Coase would be turning in their graves.

The efficient firm sizes are the sizes that survived in competition against other sizes. To survive, a firm must rise above all of problems it faces such as employee relations, skills development, innovation, changing regulations, unstable markets, access to finance and new entry. This is the decisive (and Darwinian) meaning of efficiency from the standpoint of the individual firm (Stigler 1958). One method of organisation supplants another when it can supply at a lower price (Marshall 1920, Stigler 1958).

What is even more distressing is the Commerce Commission is applying their archaic concept of competition to an industry subject to rapid innovation. Regulating innovation through competition law is never a good idea. The more efficient sized firms are the firm sizes that are expanding their market shares in the face of competition; the less efficient sized firms are those that are losing market share (Stigler 1958, 1987; Alchian 1950; Demsetz 1973, 1976).

https://twitter.com/balajis/status/465585152584716289

If the firm size distribution in an industry is relatively stable for a time, the firms are their current sizes because there are no more gains from further changes in size in light their underlying demand and cost conditions (Stigler 1983; Alchian 1950; Demsetz 1973, 1976).

Temporary monopoly and rapidly changing market shares with the occasional dominant firm are all characteristics of the early stages of any new or innovating industry. The deadweight social losses from the enforcement of competition law are at their greatest in industries undergoing rapid innovation because of the possibility of error is at its height. Optimum firm sizes continually change over time because of shifts in input and output prices and technological progress (Stigler 1958, 1983).

The Netflix Effect (via @Mark_J_Perry) http://t.co/LkDjfarRZa—

Michael Hendrix (@michael_hendrix) August 11, 2015

If large firm size is better at serving consumers, the large firms start to grow and smaller firms will die or be absorbed until the untapped gains from growth in firm size are exhausted. Firms increase in size and decrease in number when this adaptation becomes necessary to survive. If a smaller firm size is now better, smaller firms will multiply and the larger firms will decline in size because they are under-cut on price and quality.

The life cycle of many industries starts with a burst of new entrants with similar products. These new or upgraded products often use ideas that cross-fertilise. In time, there is an industry shakeout where a few leapfrog the rest with cost savings and design breakthroughs to yield the mature product (Jovanovic and MacDonald 1994a; Boldrin and Levine 2008, 2013). Fast-seconds and practical minded latecomers often imitate and successfully commercialise ideas seeded by the market pioneers using prior ideas as knowledge spillovers. Their large market shares are their prizes for winning the latest product races, not the basis of their initial victories.

New entrants regard a large firm size as a premature risk rather than an advantage of incumbency they should mimic as soon as they can. New firms set-up on a scale that is well below the minimum efficient production scale for their industry (Bartelsman, Haltiwanger, and Scarpetta 2009). New entrants choose to start so small to test the waters regarding their true productivity and the market’s acceptance of their products and to minimise losses in the event of failure (Jovanovic 1982; Ericson and Pakes 1995; Dhawan 2001; Audretsch, Prince and Thurik 1998; Audretsch and Mahmood 1994).

Competition law can subvert competition by stymieing the introduction of new goods and the temporary monopoly often necessary to recoup their invention costs and induce innovation. The puzzlingly large productivity differences across firms even in narrowly defined industries producing standard products lead to doubts about the efficiency of some firms, often the smaller firms in an industry. Some firms produce half as much output from the same measured inputs as their market rivals and still survive in competition (Syverson 2011). This diversity reflects inter-firm differences in managerial ability, organisational practices, choice of technology, the age of the business and its capital, location, workforce skills, intangible assets and changes in demand and productivity that are idiosyncratic to each individual firm (Stigler 1958, 1976, 1987; De Alessi 1983).

Technological progress comes from innovations that are the result of profit orientated research and development in the course of market competition. The two main inputs into innovation are the private expenditures of prospective innovators on R&D workers and equipment and the publicly available stock of knowledge on which they hope to build (Aghion and Howitt 2008). Any profits of successful innovators last until others innovate to supersede previous innovations (Aghion and Howitt 2008).

Harold Demsetz argued that competition does not take place upon a single margin, such as price competition. Competition instead has several dimensions often inversely correlated with each other. Because of this, a competition law disparaging one form of competition will result in more of another. There are trade-offs between innovation and current price competition. Manne and Wright noted in the paper, Innovation and the Limits of Antitrust that:

Both product and business innovations involve novel practices, and such practices generally result in monopoly explanations from the economics profession followed by hostility from the courts (though sometimes in reverse order) and then a subsequent, more nuanced economic understanding of the business practice usually recognizing its pro-competitive virtues.

A competition law enforcement authority should never pretend to know which trade-off between innovation and price competition and between competition and temporary monopoly are optimal. Every competition authority should simplify the regulatory environment by simply saying lower prices are per always lawful. The New Zealand Commerce Commission should do this but it has not.

I have not even touched on the use of competition law to subvert competition such is the pursuit of Microsoft and Google by its business rivals through competition law.

The easiest way to tell if a merger is pro-competition is if the remaining firms in the market oppose it. If it was anti-competitive, they could match the higher prices of the merged firm. The reason they oppose the merger is the merged firm will start undercutting them on price. When was the last time a competitor complained about their rivals putting their prices up? Either they hold their prices and take their business or follow their pricing lead: can’t lose.

Milton Friedman predicted this police calling card to competing drug gangs

15 Aug 2015 2 Comments

in applied price theory, economics of bureaucracy, economics of crime, history of economic thought, industrial organisation, law and economics, liberalism, Milton Friedman, Public Choice Tags: cartel theory, crime and punishment, criminal deterrence, organised crime, war on drugs

My favourite John Maynard Keynes quote

10 Aug 2015 1 Comment

in history of economic thought Tags: conjecture and refutation, growth of knowledge, John Maynard Keynes

@TelasonGetachew och vad är det för fel på det budskapet? Är det fel att partier som KD ändrar sig? @Budoarstamning http://t.co/56rL7slJJg—

Old Whig (@aClassicLiberal) July 28, 2015

Karl Marx died today for the first time

07 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in history of economic thought, Marxist economics Tags: Karl Marx

Did fiscal austerity in 2010 have credible academic support?

05 Aug 2015 1 Comment

#Greece austerity gauge. Greek government spending has fallen 20% since 2008. In UK and Italy it's up. #GreekCrisis http://t.co/WMQBxxVFqq—

RBS Economics (@RBS_Economics) July 07, 2015

One measure of the scale of austerity in Greece…and other advanced economies. http://t.co/PxCLagdd3L—

RBS Economics (@RBS_Economics) July 06, 2015

The employment level in #Greece is back to where it was in 1985. It's the equivalent of the UK losing 6 million jobs. http://t.co/AAWHMEFwfK—

RBS Economics (@RBS_Economics) July 06, 2015

Did the GFC catch modern macroeconomists by surprise?

03 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, currency unions, economic growth, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, history of economic thought, law and economics, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: bank panics, bank runs, banking crises, currency crises, Thomas Sargent

@sjwrenlewis The stimulus package ignored what we have learned in the last 60 years of macroeconomic research

02 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, history of economic thought, macroeconomics, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: Brad Delong, fiscal multiplier, fiscal stimulus, Larry Summers, New Keynesian macroeconomics, Thomas Sargent

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3966560/11754389_920572351334762_1285855543300283646_o.jpg)

Recent Comments