Meanwhile … in Germany, unemployment has fallen to a 30 year low #econ2 #f585 pic.twitter.com/kOEyEVu3HG

— Tutor2u Geoff (FRSA) (@tutor2uGeoff) January 29, 2015

Germany had major labour market deregulation on the eve of the global financial crisis

31 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

Offsetting behaviour alert: only fools and politicians would believe that a minimum wage increase increases net pay and conditions

20 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in income redistribution, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: minimum wage, offsettinh behaviour, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

John Schmitt lists 11 margins along which a minimum wage might cause changes in net pay and conditions:

- Reduction in hours worked (because firms faced with a higher minimum wage trim back on the hours they want),

- Reduction in non-wage benefits (to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage),

- Reduction in money spent on training (again, to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage),

- Change in composition of the workforce (that is, hiring additional workers with middle or higher skill levels, and fewer of those minimum wage workers with lower skill levels),

- Higher prices (passing the cost of the higher minimum wage on to consumers),

- Improvements in efficient use of labour (in a model where employers are not always at the peak level of efficiency, a higher cost of labour might give them a push to be more efficient),

- “Efficiency wage” responses from workers (when workers are paid more, they have a greater incentive to keep their jobs, and thus may work harder and shirk less),

- Wage compression (minimum wage workers get more, but those above them on the wage scale may not get as much as they otherwise would),

- Reduction in profits (higher costs of minimum wage workers reduces profits),

- Increase in demand (a higher minimum wage boosts buying power in overall economy), and

- Reduced turnover (a higher minimum wage makes a stronger bond between employer and workers, and gives employers more reason to train and hold on to worker.

Richard McKenzie argues that the biggest impact of a minimum wage increase is reductions to paid and unpaid benefits for minimum wage workers, including health insurance, store discounts, free food, flexible scheduling, and job security resulting from higher-skilled workers drawn to the higher minimum wage jobs:

- Masanori Hashimoto found that under the 1967 minimum-wage hike, workers gained 32 cents in money income but lost 41 cents per hour in training—a net loss of 9 cents an hour in full-income compensation.

- Other researchers in independently completed studies found more evidence that a hike in the minimum wage undercuts on-the-job training and undermines covered workers’ long-term income growth.

- Wessels found that the minimum wage caused retail establishments in New York to increase work demands by cutting back on the number of workers and giving workers fewer hours to do the same work.

- Fleisher, Dunn, and Alpert found that minimum-wage increases lead to large reductions in fringe benefits and to worsening working conditions.

- Marks found that workers covered by the federal minimum-wage law were also more likely to work part time, given that part-time workers can be excluded from employer-provided health insurance plans.

McKenzie also argued that if the minimum wage does not cause employers to make substantial reductions in fringe benefits and increases in work demands, then an increased minimum should cause

(1) An increase in the labour-force-participation rates of covered workers (because workers would be moving up their supply of labour curves),

(2) A reduction in the rate at which covered workers quit their jobs (because their jobs would then be more attractive), and

(3) A significant increase in prices of production processes heavily dependent on covered minimum-wage workers.

Wessels found that minimum-wage increases had exactly the opposite effect as intended: labour force participation rates went down; job quit rates went up, and prices did not rise appreciably.

These are findings by Wessels are consistent only with the view that minimum-wage increases make workers worse off, rather than better off in terms of net pay and conditions. After the minimum wage increase, the net advantages and disadvantages of menial jobs are less than before. Fewer workers enter the workforce and more quit their jobs.

McKenzie was the first economist to argue that a minimum wage increase may actually reduce the labour supply of menial workers. Employment in menial jobs may go down slightly in the face of minimum-wage increases not so much because the employers don’t want to offer the jobs, but because fewer workers want these menial jobs that are offered.

The repackaging of monetary and non-monetary benefits, greater work intensities and fewer training opportunities make these jobs less attractive relative to their other options. This reduction in labour supply by low skilled workers is why the voluntary quit rate among low-wage workers goes up, not down, after a minimum wage increase. As McKenzie explains

Economists almost uniformly argue that minimum wage laws benefit some workers at the expense of other workers.

This argument is implicitly founded on the assumption that money wages are the only form of labour compensation. Based on the more realistic assumption that labour is paid in many different ways, the analysis of this paper demonstrates that all labourers within a perfectly competitive labour market are adversely affected by minimum wages.

Although employment opportunities are reduced by such laws, affected labour markets clear. Conventional analysis of the effect of minimum wages on monopsony markets is also upset by the model developed.

McKenzie argues that not accounting for offsetting behaviour led to a fundamental misinterpretation in the empirical literature on the minimum wage. That literature shows that small increases in the minimum wages does not seem to affect employment and unemployment by that much.

…. wage income is not the only form of compensation with which employers pay their workers. Also in the mix are fringe benefits, relaxed work demands, workplace ambiance, respect, schedule flexibility, job security and hours of work.

Employers compete with one another to reduce their labour costs for unskilled workers, while unskilled workers compete for the available unskilled jobs — with an eye on the total value of the compensation package.

With a minimum-wage increase, employers will move to cut labour costs by reducing fringe benefits and increasing work demands

Proponents and opponents of minimum-wage hikes do not seem to realize that the tiny employment effects consistently found across numerous studies provide the strongest evidence available that increases in the minimum wage have been largely neutralized by cost savings on fringe benefits and increased work demands and the cost savings from the more obscure and hard-to-measure cuts in nonmoney compensation.

McKenzie is correct in arguing that the empirical literature on the minimum wage is dewy-eyed. The first assumption about any regulation is the market will offset it significantly.

In the course of undoing the direct effects of the regulation, there will be unintended consequences such as the remixing of wage and nonwage components of remuneration packages of low skilled workers covered by the minimum wage. Greg Mankiw concludes that:

The minimum wage has its greatest impact on the market for teenage labour. The equilibrium wages of teenagers are low because teenagers are among the least skilled and least experienced members of the labour force.

In addition, teenagers are often willing to accept a lower wage in exchange for on-the-job training. . . . As a result, the minimum wage is more often binding for teenagers than for other members of the labour force.

Milton Friedman – Case Against Equal Pay for Equal WorkY

15 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, discrimination, economic history, gender, labour economics, labour supply, liberalism, minimum wage Tags: equal pay, Milton Friedman

Some Ground Rules for the Minimum Wage debate

12 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in econometerics, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: methodology of economics, minimum wage

This is the best single paper I’ve seen written on the methodology of the minimum wage debate.

From a great blog I have just discovered, the author gives a good kicking to both sides for empiricial sloppiness, advocacy bias and plain bad economics. He also explains how to lift your game no matter where you are on the political spectrum.

Naturally, the author, Michael Tontchev, is an economics undergraduate.

My latest article for Turning Point USA. I suggest some aspects of the debate that just need to go away. Your thoughts?

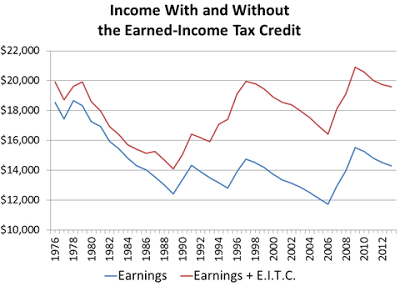

EITC is better than the Minimum Wage

15 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, labour economics, liberalism, minimum wage, poverty and inequality Tags: earned income tax credit, family tax credits, in-work tax credits, minimum wage, negative income tax, poverty and inequality

Why some economists would not oppose minimum wage increases

04 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

In 1965 an editor at Look asked an MIT economist why "liberal" economists hadn't signed an anti-minimum wage letter. http://t.co/ONuQKIWhG7—

Garett Jones (@GarettJones) December 02, 2014

Lindsay Mitchell – Labour’s Carmel Sepuloni: be careful what you ask for

01 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, labour economics, labour supply, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: Carmel Sepuloni, inequality and poverty, James Heckman, James Julius Wilson, labour economics, Roland Fryer, welfare reform

Lindsay Mitchell has a nice blog today on the views of the new Labour Party spokesman on social development – the New Zealand ministerial portfolio covering social security and social welfare

Carmen Sepuloni disagrees with National Party’s policy of requiring solo mothers to look for work. She believed there should be support for sole parents to return to work, but not a strict compulsion:

It is a case by case basis. I don’t think it should be so stringent because it’s not necessarily to the benefit of their children.

The American sociologist James Julius Wilson in The Truly Disadvantaged (1987) and When Work Disappears (1996) wrote about how more children are growing-up without a working father living in the home and thereby gleaning the awareness that work is a central expectation of adult life:

. . . where jobs are scarce, where people rarely, if ever, have the opportunity to help their friends and neighbors find jobs. . . many people eventually lose their feeling of connectedness to work in the formal economy; they no longer expect work to be a regular, and regulating, force in their lives.

In the case of young people, they may grow up in an environment that lacks the idea of work as a central experience of adult life — they have little or no labor force attachment.

Carmel Sepuloni appears to believe that work is not a central expectation of adult life. Hard work used to be a core value of the Labour Party.

The toughest week of door knocking for the Labour Party in the 2011 general elections was after the Party promised that the in-work family tax credit should also be paid to welfare beneficiaries.

Voters in strong Labour Party areas were repulsed by the idea. These working-class Labour voters thought that the in-work family tax credit was for those that worked because they had earnt it through working on a regular basis. The party vote of the Labour Party in the 2011 New Zealand general election fell to its lowest level since its foundation in 1919 which was the year where it first contested an election.

When Sepuloni was on the Backbenchers TV show prior to the recent NZ general election, she was asked by the host whether she would support a $40 per hour minimum wage if that would mean equality. She did not hesitate to say yes.

Sepuloni does not seem to have noticed that wages must have something to do with the value of what you produce and the ability of your employer to sell it at a price that covers costs.

The economic literatures (Heckman 2011; Fryer 201o) and sociological literatures (Wilson 1978, 1987, 2009, 2011), particularly in the U.S. is suggesting that skill disparities resulting from a lower quality education and less access to good parenting, peer and neighbourhood environments produce most of the income gaps of racial and ethnic minorities rather than factors such as labour market discrimination.

Grounds for optimism about the effectiveness of welfare reform in overcoming barriers to employment lie in the success of the 1996 federal welfare reforms in the USA.

The subsequent declines in welfare participation rates and gains in employment were largest among the single mothers previously thought to be most disadvantaged: young (ages 18-29), mothers with children aged under seven, high school drop-outs, and black and Hispanic mothers. These low-skilled single mothers who were thought to face the greatest barriers to employment. Blank (2002) found that:

At the same time as major changes in program structure occurred during the 1990s, there were also stunning changes in behavior. Strong adjectives are appropriate to describe these behavioral changes.

Nobody of any political persuasion-predicted or would have believed possible the magnitude

of change that occurred in the behavior of low-income single-parent families over this decade.

People have repeatedly shown great ability to adapt and find jobs when the rewards of working increase and eligibility for welfare benefits tighten.

via Lindsay Mitchell: Carmel Sepuloni: be careful what you ask for.

In the good old days, everyone agreed on the employment effects of minimum wage laws, even their supporters

28 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

The Best Minimum Wage Story Of The Day, Or, Yes, Wage Rises Really Do Kill Jobs

30 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, unemployment, unions Tags: living wage, minimum wage

Coalition Celebrating Equal Pay Case Outcome

29 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, gender, income redistribution, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand, rentseeking Tags: gender wage gap, living wage, minimum wage, pay equity

I wonder who will pay for this? Caregiver wages are funded out of a fixed budget allocated by the government.

A higher wage will change the type of worker that the caregiving sector will seek to recruit, as happened after increases in the teenage went minimum wage.

When the teenage minimum wage went up in New Zealand, employment of 17 and 18-year-olds fell, while the employment of 18 to 19-year-olds increased because the latter were more mature and reliable than the younger contemporaries.

Pay Equity Challenge Coalition

Media release: Pay Equity Challenge Coalition

28 October 2014

Coalition Celebrating Equal Pay Case Outcome

“The Court of Appeal’s decision declining the employers’ appeal in the Kristine Bartlett case is a huge victory for women workers” said Pay Equity Coalition Challenge spokesperson Angela McLeod.

“The Courts’ decision that equal pay may be determined across industries in female-dominated occupations revitalises the Equal Pay Act 1972 and will be a major factor in closing New Zealand’s stubborn 14 percent gender pay gap”.

The judgement by the Court of Appeal upholding the Employment Court decision again validates the work of caregivers and that they are underpaid, she said.

“We commend the Service and Food Workers Union Nga Ringa Tota in taking this case and exposing the underpayment and undervaluation of aged care workers. And the decision is a victory for all the women’s organisations who have never given up fighting for equal pay,”…

View original post 92 more words

Recent Comments