via The unbelievable rise of single motherhood in America over the last 50 years – The Washington Post.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

19 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: causes of poverty, single parenthood

via The unbelievable rise of single motherhood in America over the last 50 years – The Washington Post.

15 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, labour economics, liberalism, minimum wage, poverty and inequality Tags: earned income tax credit, family tax credits, in-work tax credits, minimum wage, negative income tax, poverty and inequality

13 Dec 2014 1 Comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, labour economics, liberalism, poverty and inequality Tags: causes of poverty, inequality and poverty, school breakfast programmes, The Great Fact

13 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, poverty and inequality Tags: gender wage gap, Gini coefficient, poverty and inequality, top 1%

What is claimed to have gone wrong by the op-ed in The Guardian overnight?

A stark rich-poor divide, the OECD argued, had taken over a third off the country’s economic growth rate in the last 20 years. But how could this be?

The simple answer is that in the two decades from 1985 onwards, New Zealand had the biggest increase in income gaps of any developed country.

Incomes for the richest Kiwis doubled, while those of the poorest stagnated. Middle income earners didn’t do too well, either.

Are these claims true? That is, in the two decades from 1985 onwards, have the incomes of the richest Kiwis doubled, while those of the poorest stagnated and have a middle income earners not done too well either?

Figure 1 shows that prior to the recent recession starting in 2009, there were 15 years of steady growth in median household incomes. As will be shown, most of the period covered both by the op-ed in the Guardian, and by the OECD paper was an economic boom.

Figure 1: Real household income trends before housing costs (BHC) and after housing costs (AHC), 1982 to 2013 ($2013)

Source: Bryan Perry, Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2013. Ministry of Social Development (July 2014).

Perry (2104) found that net income gains from the mid-1990s to 2013 were similar for all income groups, so income inequality in 2013 was also similar to the mid-1990s – see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Real household incomes (BHC), changes for top of income deciles, 1994 to 2013

Source: (Perry 2014).

Importantly, in the OECD analysis, much was made of what was happening to the 40% income decile. As can be seen from figure 2, this decile gained as much as any other group in New Zealand from the income growth between 1994 and 2013.

The Gini coefficient in figure 3 , which years the most common measure of inequality, shows no evidence of a rise in income inequality since the mid-1990s. The trend-line of the genie coefficient in figure 3 is almost flat since the early 1990s .

Figure 3: Gini coefficient New Zealand 1980-2015

Source: (Perry 2014).

To make things more awkward, the large increase in income inequality in New Zealand in the late 1980s and early 1990s shown in figure 3 was followed by a 15 year economic boom after 20 years of economic stagnation – next to no income growth – as is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Real GDP per New Zealander and Australian aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1956-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

The lost decades of the growth in the 1970s and 1980s were replaced with a long boom. Trend growth of 2% per year returned after this increase in inequality – see figure 4.

The gains since the economic boom since the early 1990s has been broadly based both up and down the income distribution and by ethnicity. As shown in figure 5, between 1994 and 2010, real equivalised median household income rose 47% from 1994 to 2010; for Māori, this rise was 68%; for Pasifika, the rise was 77%.

Figure 5: Real equivalised median household income (before housing costs) by ethnicity, 1988 to 2013 ($2013).

Source: (Perry 2014).

These improvements in Māori incomes since 1992 were based on rising Māori employment rates, fewer Māori on benefits, more Māori moving into higher paying jobs, and greater Māori educational attainment should be celebrated and consolidated. Māori unemployment reached a 20-year low of 8 per cent from 2005 to 2008.

As for the top 1%, as shown by Figure 6, their income share has been steady at 8-9% since the mid-1990s. It was only in the USA the top 1% share continued to rise strongly, from 13% to 19%.

Figure 6: income shares of the top 1% of earners, New Zealand, Australia and USA

source: Top incomes database

Over the last more than two decades in New Zealand, there has been sustained income growth spread across all of society. Perry (2014) concluded that:

Overall, there is no evidence of any sustained rise or fall in inequality in the last two decades.

The level of household disposable income inequality in New Zealand is a little above the OECD median.

The share of total income received by the top 1% of individuals is at the low end of the OECD rankings.

What is claimed as the causes of this growing rich-poor divide that is also slowing growth by a third?

Tracing the causes of a growing income gap is like trying to map earthquake fault lines – never a precise science – but it is hard to ignore the correlation between the timing of the increase and the country’s post-1984 political revolution.

Embracing reforms known elsewhere as Thatchernomics and Reaganomics with unprecedented enthusiasm, New Zealand halved its top tax rate, cut benefits by up to a quarter of their value, and dramatically reduced the bargaining power – and therefore the share of national income – of ordinary workers.

Thousands of people lost their jobs as manufacturing work went overseas, and there was no significant response with increased trade training or skills programmes, a policy failure that is on-going.

At the same time, New Zealand stopped building affordable houses in any serious quantity, forcing poorer households to spend ever-increasing amounts on rent and mortgages.

As will be recalled from Figure 4, the economic reforms in New Zealand were followed by a long economic boom starting in 1992 that only came to an end with the onset of the global financial crisis.

Figure 7 shows that from 1994, the proportion of the lowest income households spending more than 30% of their income on housing fell steadily, reaching 34% by 204.

Figure 7: Proportion of households spending more than 30% of their income on housing costs by income quintile, New Zealand 1988–2013 HES years

Source: Perry (2014)

Housing affordability was improving for much of the period in which the op-ed in the Guardian was claiming it was getting worse. The increase in housing unaffordability in the late 1980s and early 1990s coincided with a deep recession and a cut in welfare benefits.

Housing affordability has become an issue in New Zealand because of rising prices. Supply is not keeping up with demand.

There were considerable increases in prices throughout the house price distribution between 2004 and 2008. Median house price increasing by over 50% between 2004 and 2008; the price rises were largest among the lower price houses.

It was not a case of a decline in demand under the hypothesis that is put forward in the op-ed in the Guardian. For that hypothesis to hold, housing prices would somehow have to fall in the price range of ordinary workers. That is not the case.

Furthermore, the large increase in housing prices and decline in housing affordability occurred a decade and more after the increase in inequality in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The timing is out.

Another inconvenience for the rich poor divide hypothesis is during the housing price boom after 2004 rent to disposable income for all income quintiles remained relatively constant. Rents were stable.

Poorer households are more likely to rent, and therefore much less likely to be affected by the housing affordability crisis in New Zealand as that was mostly about home ownership.

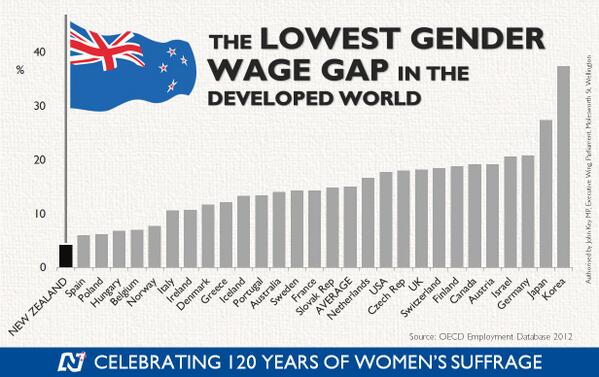

Gender analysis! Gender analysis? Where is the gender analysis? Over the last 20 to 30 years, the gender gap has closed substantially in terms of wages and employment. Young women now outnumber young men two to one at university.

New Zealand has the smallest gender wage gap in the Western world. That is inconsistent with the notion in New Zealand has a rich poor divide. Instead New Zealand appears to be an egalitarian paradise as long as you are not a boy!

The major driver of inequality in New Zealand and overseas is the rising number of two-income households made up of two well-educated parents and one or two children and many more single parent households on low pay or no one in paid employment in the house. Well-educated couples form into high income households; fewer of the less educated marry and too many end up a single mothers.

Source: closertogether.org.nz

The main cause of poverty in New Zealand is dependency on welfare benefits and in particular the number of single parents. Child poverty in beneficiary families is 75% to 80%, much higher than in families with at least one adult in full-time employment (11% in 2012 and 2013). The payment of welfare benefits to families who do not work guarantees an income to people not in a job, but it creates incentives not to work.

The economic and sociological literatures overseas increasingly suggesting that skill disparities resulting from a lower quality education and less access to good parenting, peer and neighbourhood environments produce most of the income gaps of racial and ethnic minorities rather than factors such as labour market discrimination.

12 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: labour economics, welfare reform

Paradoxically, the main way of using financial incentives to increase net labour supply of beneficiaries and move more off the benefit is to toughen the benefit abatement regime.

This increase in the abatement rates on welfare benefits for earned income moves more off the benefit and moves more into full-time employment but still with an ambiguous effect on part-time employment. Some may prefer the benefit over their current part-time job.

The notion that tinkering with financial incentives will not have large effects on labour supply and benefit numbers is not new. Increase in the generosity of welfare benefits with increase the number of applicants.

Tinkering with the details of abatement rates and thresholds has ambiguous labour supply effects because exits from welfare are still offset by new entry onto welfare. The netting the labour supply changes of these diverse groups often leads to welfare reform leading to positive but small change in labour supply. Quantitatively, an old finding is the remarkable lack of effects of financial incentives on welfare participation (Moffitt 1992, 2002).

Under a move up to a 100 per cent benefit abatement rate as shown in Figure 1; arrow 1 in Figure 1 shows that some who were working part-time will now find not working at all to be the more attractive option. The new 100 per cent benefit abatement rate reduces their take-home pay but they enjoy more leisure time.

Figure 1: the labour supply effects of an increase to a 100 per cent benefit abatement rate

Arrow 2 in Figure 1 shows that some part-time workers increase their working hours because working a little more mitigates the reduction in their take-home pay and allow some leisure time.

Arrow 3 in Figure 1 shows that some part-timers return to full-time working hours because of the revised leisure-labour trade off that now makes a somewhat higher take-home pay worthwhile despite reduced leisure time.

Whether net labour supply increases or falls after a rise in the benefit abatement rate to 100 per cent depends on the relative numbers of workers at different points on the budget constraint that are working full-time, not working, and working part-time and the magnitudes of their responses.

Some will stay as they are working either full-time, not working or working part-time. Others supply more labour. Working more hours may increase their take-home pay depending on how productivity they are.

Some part-timers will move to full-time in low paid jobs with take-home pay because of the loss of benefit income, they will enjoy less leisure time and there can be additional costs such as child care.

More productive workers in better paid jobs will take home more in pay by moving to full-time but will enjoy less leisure time. Some workers that were previously working part-time stop working and rely in welfare benefits.

If reduced welfare dependence is the objective, high abatement rates and low abatement thresholds are the path to follow. With a move to 100 per cent abatement of benefits, some leave the welfare system but no one joins it because of the higher abatement rate.

Less generous abatement will see some who claim the benefit while working part-time move to a lower take-home pay. Some will be on a higher take-home pay working full-time. The net labour supply effect is ambiguous because some leave work altogether while others work more hours.

The net labour supply depends on the relative numbers at different points on the budget constraint working full-time, not working, or working part-time and the magnitudes of their respective individual labour supply responses. Some people will stay as they are working full-time, not working or working part-time.

No one who previously did not work is worse off under the benefit abatement rate increase to 100 per cent because they are unaffected by abatement. Some who were working part-time and previously claiming the benefit take-home less but enjoy more leisure as shown by arrow 2 in Figure 1. The remaining part-time workers now take-home more pay but enjoy less leisure because they are working more hours and even full-time as shown by arrow 3 in Figure 1.

The blogs so far

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

11 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in economics of education, human capital, international economics, labour supply, occupational choice, poverty and inequality Tags: Bryan Caplan, Charles Murray, IQ and education, poverty and inequality, signalling

Charles Murray has been cooking with gas lately – on fire. One of his points is too many go to college. Murray points out that succeeded at college requires an IQ of at least 115 but 84% of the population don’t have this:

Historically, an IQ of 115 or higher was deemed to make someone “prime college material.”

That range comprises about 16 per cent of the population.

Since 28 per cent of all adults have BAs, the IQ required to get a degree these days is obviously a lot lower than 115.

Those on the margins of this IQ are getting poor advice to go to college. Murray argues that other occupational and educational choices would serve them better in light of their abilities and likelihood of succeeding at college. Moreover, Murray is keen on replacing college degrees with certification after shorter periods of study such as in the certified public accountants exam.

Murray believes a lot of students make poor investments by going on to College, in part, because many of them don’t complete their degrees:

…even though college has been dumbed down, it is still too intellectually demanding for a large majority of students, in an age when about 50 per cent of all high school graduates are heading to four-year colleges the next fall.

The result is lots of failure. Of those who entered a four-year college in 1995, only 58 per cent had gotten their BA five academic years later.

Murray does not want to abandon these teenagers:

Recognizing the fact that most young people do not have ability and/or the interest to succeed on the conventional academic track does not mean spending less effort on the education of some children than of others.

…Too few counsellors tell work-bound high-school students how much money crane operators or master stonemasons make (a lot).

Too few tell them about the well-paying technical specialties that are being produced by a changing job market.

Too few assess the non-academic abilities of work-bound students and direct them toward occupations in which they can reasonably expect to succeed.

Worst of all: As these students approach the age at which they can legally drop out of school, they are urged to take more courses in mathematics, literature, history and science so that they can pursue the college fantasy. Is it any wonder that so many of them drop out?

To add to that, he is in the Bryan Caplan School: education is often an elaborate former of signalling for many degrees. Murray says that college is a waste of time because:

Outside a handful of majors — engineering and some of the sciences — a bachelor’s degree tells an employer nothing except that the applicant has a certain amount of intellectual ability and perseverance.

Even a degree in a vocational major like business administration can mean anything from a solid base of knowledge to four years of barely remembered gut courses.

If the OECD is to be believed, that not enough people are going to college from lower middle class families, obviously IQ is not one of the constraints on access to college Charles Murray suggested it to be.

The growing strength of the case that education is a form of signalling is a literature that the now famous OECD paper reviewed, found wanting, but did not have time to discuss in the working paper.

Another contemporary theme the OECD paper reviewed, found wanting, but did not have time to discuss is a large number of graduates who end up holding jobs that do not require a university education – going to college:

About 48 per cent of employed U.S. college graduates are in jobs that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) suggests requires less than a four-year college education.

Eleven per cent of employed college graduates are in occupations requiring more than a high-school diploma but less than a bachelor’s, and 37 per cent are in occupations requiring no more than a high-school diploma.

The proportion of overeducated workers in occupations appears to have grown substantially; in 1970, fewer than one per cent of taxi drivers and two per cent of fire-fighters had college degrees, while now more than 15 per cent do in both jobs

All in all, the OECD has gone into the dragons den by backing the accumulation of human capital as its mechanism to link inequality with lower growth. No matter how you spin it, this linking of lower economic growth to greater inequality through financial constraints on the accumulation of human capital by the lower middle class was a bold hypothesis.

The case for investing more in education is not a slam dunk. Higher education – university or polytechnic – is a rat race that many don’t need to join.The case for the government paying a great many more to join that rat race is rather weak.

11 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in economics of education, human capital, labour economics, occupational choice, poverty and inequality Tags: educational attainment, human capital, poverty and inequality, student loans, tuition fees

The analysis of the OECD published overnight depends crucially upon how greater inequality reduces the ability of the lower income families to invest in human capital.

The OECD theory of inequality and lower growth is there is a financing constraint because of inequality that reduces economic growth because of less human capital accumulation by lower income families.

Proportion of adults aged 25–64 years with an educational qualification of at least upper secondary level and tertiary level, 1991–2009

In a nutshell, not enough people are going to university. Apparently, the explosion in tertiary educational attendance over the last generation, an increase of about 150% for the adult population aged 25 to 64, was just not good enough.

But what about adults aged 25 to 34, recent graduates, how many of them are there?

There was an explosion of young New Zealanders in the late 1990s who qualified for a degree from a university or diploma from a Polytech.

Under the hypothesis of the OECD about financial constraints retarding the accumulation of human capital among the lower middle class – the fourth decile of the income distribution – even more young New Zealanders should have gone to university or Polytech.

Are there many New Zealanders left who are qualified and suited to tertiary education who do not go?

That is the crux of the OECD position: not enough lower-middle-class New Zealanders go on to obtain higher education and upgrade their skills because of financial constraints in a country was in interest free student loans, means tested student allowances, and the government subsidises for 75% of all tuition fees. Tuition fees only equal 25% of the actual cost and any one can get a student loan to cover this fee.

10 Dec 2014 2 Comments

in economic growth, economics, economics of education, human capital, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, poverty and inequality Tags: financing constraint on education, inequality and economic growth, poverty and inequality, student loans, taxation and the labour supply, top 1%

Figure 1: Estimated consequences of changes in inequality (1985 – 2005) on subsequent cumulative growth (1990-2010)

Drawing on harmonised data covering the OECD countries over the past 30 years, the econometric analysis suggests that income inequality has a negative and statistically significant impact on subsequent growth.

In particular, what matters most is the gap between low income households and the rest of the population.

In contrast, no evidence is found that those with high incomes pulling away from the rest of the population harms growth.

The paper also evaluates the “human capital accumulation theory” finding evidence for human capital as a channel through which inequality may affect growth.

Analysis based on micro data from the Adult Skills Survey (PIAAC) shows that increased income disparities depress skills development among individuals with poorer parental education background, both in terms of the quantity of education attained (e.g. years of schooling), and in terms of its quality (i.e. skill proficiency).

Educational outcomes of individuals from richer backgrounds, however, are not affected by inequality.

via Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth – Papers – OECD iLibrary.

The OECD analysis published overnight in Paris suggest that the increase in equality in New Zealand the late 1980s is still scarring economic growth today by about 15 percentage points in lost cumulative economic growth.

The analysis of the OECD published overnight depends crucially upon how greater inequality reduces the ability of the lower income families to invest in human capital:

The evidence strongly suggests that high inequality hinders the ability of individuals from low economic background to invest in their human capital, both in terms of the level of education but even more importantly in terms of the quality of education.

The OECD theory of inequality and lower growth is there is a financing constraint because of inequality that reduces economic growth because of less human capital accumulation by lower income families.

This is interesting because in 2002, with Pedro Carneiro, James Heckman showed that lack of credit is not a major constraint on the ability of young Americans to attend college. They found that credit constraints prevent, at most, 4% of the U.S. population from attending. Credit constraints is weakening as a rationale for a lack of an accumulation of human capital, and can be easily solved.

The OECD is putting a lot of their growth inequality nexus eggs in one basket. That student loans and other government interventions are not closing credit constraints on financing higher education.

To add to that basket , they are placing a lot of weight in human capital as a driver of growth, and in New Zealand’s case, of technology absorption, which is a main foundation of economic growth in New Zealand. The evidence that human capital is a key contributor to higher economic growth is weakening ruck rather than strengthening.

The trend rate of productivity growth did not accelerate over the 20th century despite a massive rise in investments in human capital and R&D because of the rising cost of discovering and adapting new technological knowledge. The number of both R&D workers and highly educated workers increased many-fold over the 20th century in New Zealand and other OECD member countries including the global industrial leaders such as the USA, Japan and major EU member states.

Higher education has been free for the low income families for several generations. Student loans are readily available. It is hard to believe that such a readily solvable problem is a major source of inequality and lower growth.

Cross-country differences in total factor productivity are due to differences in the technologies that are actually used by a country and the degree in the efficiency with which these technologies are used. Differences in total factor productivity, rather than differences in the amount of human capital or physical capital per worker explain the majority of cross-country differences in per capita real incomes (Lucas 1990; Caselli 2005; Prescott 1998; Hall and Jones 1999; Jones and Romer 2010).

Differences in the skills of the individual worker or in the total stock of human capital of all workers in a country cannot explain cross national differences in value added per worker at the industry level.

The USA, Japan, France, the UK and Germany all have relatively well-educated, experienced and tested labour forces. For example, the 1993 McKinsey’s study inquired into the education and skills levels of Japanese and German steel workers. Comparably skilled German steel workers were half as productive as their Japanese counterparts (Prescott and Parente 2000, 2005).

As for the source of the growing income inequality, there is a long literature dating back 25-years arguing that skill-biased technological change is increasing the returns to investing in education

Important is the OECD conclusion that inequality in terms of the rich getting richer does not harm growth. To make sure I have not misquoted them , I quote once again from their abstract, where the OECD summarises its own findings:

Drawing on harmonised data covering the OECD countries over the past 30 years, the econometric analysis suggests that income inequality has a negative and statistically significant impact on subsequent growth.

In particular, what matters most is the gap between low income households and the rest of the population.

In contrast, no evidence is found that those with high incomes pulling away from the rest of the population harms growth.

That conclusion of the OECD almost saves me from having to go on about how inequality has not increased in New Zealand for the last 20 years, see figure 2, and that the top 1% have not increased their share of income in recent decades – see figure 3. The fact that the rich can get richer without harming the poor is an important conclusion that will surely not be reported by the media.

Figure 2: Gini coefficient New Zealand 1980-2015

Figure 3: Top 1% income shares, USA, New Zealand and Australia, 1970-2012

Another inconvenience for the OECD is the last major increase in Gini coefficient in New Zealand was followed by a 15 year economic firm – see figures 2 and 4.

Figure 4: Real GDP per New Zealander and Australian aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1956-2013

The NZ top 1% share has been steady at 8-9% since the mid-1990s see figure 4; the top 1%’s share rose strongly in the USA in recent decades, from 13% in the mid-1980s to 19% in 2012.

The Occupy crowd blame everything from the global financial crisis to a bad environment on growing inequality and the growing riches of living top 1%. Such an argument has no foundation in fact in New Zealand. The last major increase in Inequality was a long time ago in New Zealand.

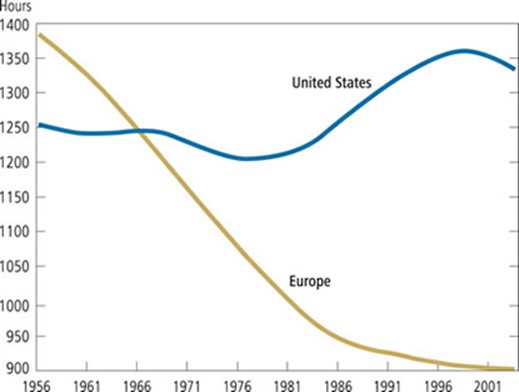

The OECD is also rather casual about how policies to redistribute wealth and increasing incomes. While Western Europe is diverse, as a group, the higher taxes in the European Union reduced incentives to work. Employment as a percentage of the population has been consistently lower in Western Europe than in the USA since the 1950s, with an average employment rate gap of 10 percentage points over 1980-2007.

Large increases in taxes on income from labour since the 1970s, enhanced incentives for retire early, and the interaction of generous employment insurance with the larger skill losses among workers displaced by the greater economic turbulence since 1980 all acted to reduce both real GDP and hours worked per week per working age person by up to a third in Western Europe as compared to the USA since the 1970s (Prescott 2004, 2007; Rogerson 2006, 2008; Ohanian et al. 2008; Ljungqvist and Sargent 1998, 2007, 2008). For example, Ohanian, Rao and Rogerson 2008 in “Work and taxes: allocation of time in OECD countries” found that:

Europeans pay more taxes, work fewer hours per year, have longer vacations, retire sooner, and invest less in human capital in an era in which trends in technology have significantly increased the demand for skilled workers, more innovation, more intense competition and greater entrepreneurial alertness. In The Impact of Labor Taxes on Labor Supply: An International Perspective (AEI Press, 2010) Rogerson finds that:

• a 10 percentage point increase in the tax rate on labour leads to a 10 to 15 per cent decrease in hours of work.

• Even a 5 per cent decrease in hours worked would mean a decline in labour output equating to a serious recession.

• While recessions are temporary, permanent changes in government spending patterns have long-lasting repercussions.

• Although government spending provides citizens with important benefits, such benefits must be weighed against the disincentive effects of increased labour taxes.

• Policymakers who fail to account for the decrease in labour output risk expanding government programs beyond their optimal scale.

Robert Lucas estimated in 1990 that eliminating all taxes on income from capital would increase the U.S. capital stock by about 35% and consumption by 7%.

Hans Fehr, Sabine Jokisch, Ashwin Kambhampati, and Laurence J. Kotlikoff (2014) found that eliminating the corporate income tax completely would raise the U.S. capital stock (machines and buildings) by 23%, output by 8% and the real wages of unskilled and skilled workers each by 12%.

In summary, this one paper by the OECD, which is a working paper makes profound conclusions about taxation and economic growth that contradict a large literature based on the lack of statistical significance of coefficients in the OECD’s regressions.

More fundamentally, linking lower economic growth to inequality through credit constraints on the human capital accumulation of the lower middle class is a weak reed to hang its argument. Human capital is not a good explanation of variations in growth across time or between countries.

What happened to income inequality in New Zealand in the late 1980s is not a credible explanation for lower growth 30 years later. Lower economic growth because of greater inequality is certainly an easy problem to solve if all that is required is more action on the financing constraint on human capital accumulation.

09 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

09 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, health economics, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: causes of poverty, economics of personality, poverty and inequality

- alcoholism: Alcohol costs money, interferes with your ability to work, and leads to expensive reckless behavior.

- drug addiction: Like alcohol, but more expensive, and likely to eventually lead to legal troubles you’re too poor to buy your way out of.

- single parenthood: Raising a child takes a lot of effort and a lot of money. One poor person rarely has enough resources to comfortably provide this combination of effort and money.

- unprotected sex: Unprotected sex quickly leads to single parenthood. See above.

- dropping out of high school: High school drop-outs earn much lower wages than graduates. Kids from rich families may be able to afford this sacrifice, but kids from poor families can’t.

- being single: Getting married lets couples avoid a lot of wasteful duplication of household expenses. These savings may not mean much to the rich, but they make a huge difference for the poor.

- non-remunerative crime: Drunk driving and bar fights don’t pay. In fact, they have high expected medical and legal expenses. The rich might be able to afford these costs. The poor can’t.

Yet as Charles Murray keeps reminding us, all of the pathologies on my list are especially prevalent among the poor.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments