What is the evidence on human capital spillovers? Evidence from the mobility of knowledge workers

17 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in economic growth, Gary Becker, human capital, job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: human capital externalities

While there is a vast literature documenting the large private returns from education and on-the-job human capital (Card 1999; Rubenstein and Weiss 2007; Almeida and Carneiro 2008), evidence of human capital spillovers is limited. Many studies find little evidence of spillovers from education (Lange and Topel (2005), Ciccone and Peri (2006)). Studies even struggle to find small spillovers from another year in high school (Acemoglu and Angrist 2001). Differences in human capital also explain only a small part of cross-national differences in incomes per capita (Hsieh and Klenow 2010; Parente and Prescott 2000, 2005).

The R&D industries offer a case study of the likely size of skills spillovers from worker mobility from large firms. The mobility of technical personnel and the human capital embodied in them across R&D firms is a substantial source of knowledge transfer (Møen 2005). For there to be a spillover, the new employer must pay recruits less than the value added by the job experience and skills they bring to the fold.

A key advantage of studying the mobility of R&D workers for skills spillovers is these industries are populated with many spin-offs founded by the ex-employees of larger firms. R&D spin-offs tend to be larger on average that other new firms and initially employ more advanced, more experienced workers and more technical specialists than do other new firms (Andersson and Klepper 2013).

Capturing the value of skills spillovers from job-hopping is a major business opportunity. The efforts of entrepreneurs to create and enforce property rights over information and other resources as their value increases are central to the organisation of both markets and firms.

A litmus test for the capture of the value of skills spillover is whether wages adjust in line with evolving career opportunities. Becker (2007, p. 134) explains this process of market adaptation and entrepreneurship as follows:

Firms introducing innovations are alleged to be forced to share their knowledge with competitors through the bidding away of employees who are privy to their secrets. This may well be a common practice, but if employees benefit from access to saleable information about secrets, they would be willing to work more cheaply than otherwise.

Møen (2005), Magnani (2006) and Maliranta, Mohnen and Rouvinen (2009) found that employers capture much of the skills spillovers to others by paying R&D workers less early in their careers; later employers pay higher wages to reflect the valued added by the human capital that these R&D recruits bring.

Andersson, Freedman, Haltiwanger, Lane and Shaw (2009) found that software firms in markets with large returns from product breakthroughs pay higher starting salaries to attract star employees. Accounting and legal firms and sports teams also pay more to recruit and retain top performers (Wezel, Cattini and Pennings 2006; Campbell, Ganco, Franco and Agarwal 2012; Rosen 2001).

Employers balance skills and knowledge acquisition through recruitment with in-house development of skills and knowledge. Mason and Nohara (2010) did not find ‘any evidence’ that the external experience of scientists and engineers is any more valuable to firms than is their internal experience.

Firms will pay a wage that equalises the returns on skills acquisition through recruitment with the returns on investing in in-house training. This equalisation of the returns between internal and external sources of skills and knowledge is consistent with competition penalising firms that pay too much or too little for inputs and rewarding entrepreneurs for superior alertness to new opportunities.

The option value of founding or working for a spin-off is also captured in the wages of R&D workers (Kitch 1980; Pakes and Nitzan 1983). Central to a spin-off is carrying on with new ideas and prototypes that the leaving employees judged to be under-valued by the parent firm and they want to build on at their own entrepreneurial risk (Klepper and Sleeper 2005; Klepper 2007).

Large firms are known for incremental innovations while small firms pioneer product break-troughs whose prospects were not as well valued inside large hierarchies (Baumol 2002, 2005; Audretsch and Thurik 2003). Many R&D spin-offs continue with emerging ideas and products that their parents were in the process of abandoning (Hellmann 2007; Chatetterjee and Rossi-Hansberg 2012; Klepper and Thompson 2010). One reason is the developing idea does not fit in with the risk profile and skills of the parent so many spin-offs are friendly (Fallick, Fleischman, and Rebitzer 2006; Chen and Thompson 2011).

Founding or working for a spin-off or start-up is a real prospect. In many innovative industries, upwards of 20 percent of new entrants are intra-industry spinoffs; these firms outperform other new entrants and disproportionately populate the ranks of industry leaders (Klepper and Thompson 2010).

The evidence of large firms spawning more entrepreneurs among scientists and engineers is mixed. Large parent firm size reduces both the probability of leaving, and more so, the probability of leaving to found a spin-off (Andersson and Klepper 2013; Sørensen 2007; Sørensen and Philipps 2011). Spin-offs are less likely from large parents because more of the skills and experience accumulated within large firms is firm-specific human capital and is therefore less mobile into a spin-off.

Scientists and engineers who worked in small firms are ‘far more likely’ to found a spin-off than are their large firm counterparts, and their spin-offs are more likely to be a success (Elfenbein, Hamilton and Zenger 2010; Sørensen and Phillips 2011). Working in smaller firms allows spin-off minded employees to gain the balance and wide array of technical knowledge and management skills that are prized in entrepreneurship (Elfenbein, Hamilton and Zenger 2010; Lazear 2004, 2005).

Working in managerial hierarchies works against founding a spin-off. Tåg, Åstebro and Thompson (2013) found that conditional on size, employees in firms with more layers of management are less likely to enter entrepreneurship, self-employing or quit to go to another firm. They attributed this to the employees in firms with fewer management layers developing a broader range of skills; multiple layers of management offering more promotion opportunities; and skill mismatch is less problematic in more hierarchical firms because there are more chances to move. The higher pay and better career opportunities in larger firms reduces job quits, and with it, skills spillovers and spin-offs.

The wage adjustments for current skills and knowledge transfer opportunities to future employers, start-ups and spin-offs are large. New science graduates accept 20 per cent less in starting pay to work where they can publish more in their own names (Stern 2004).

Scientists and engineers working in R&D accept 20 per cent less pay than other scientists and engineers who work in technical and managerial occupations to secure this more interesting work (Dupuy and Smits 2010). Gibbs (2006) suggested that the U.S. Department of Defense is able to recruit and retain engineers and scientists on low pay because they offer work on some of the most advanced technical research in the world.

Employers who pay full value in wages, share options, learning and R&D opportunities in exchange for the labour and human capital of employees are not benefiting from a skills spillover.

The evidence just reviewed identifies market processes that minimise skills spillovers from large R&D firms to spin-offs. Large firms train their employees in skills that are more often firm-specific and adjust wages to account for the career opportunities that might arise from on-the-job training that is more mobile. The employees of larger firms have longer job tenures in part because their human capital is less mobile.

The marvel of the market: the remarkable foresight of young adults in choosing what to study

16 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in Alfred Marshall, Armen Alchian, economics of education, George Stigler, human capital, job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice, politics - New Zealand, rentseeking Tags: 2nd laws of supply and demand, Alfred Marshall, Armen Alchian, george stigler, search and matching, skills shortgaes

Known but yet to be exploited opportunities for profit do not last long in competitive markets, including hitherto unnoticed opportunities for the greater utilisation and development of skills and experience (Hakes and Sauer 2006, 2007; Ryoo and Rosen 2004; and Kirzner 1992). Moneyball is the classic example of entrepreneurial alertness to hitherto unexploited job skills which were quickly adopted by competing firms (Hakes and Sauer 2006, 2007).

There is considerable evidence that the demand and supply of human capital responds to wage changes. For example, over- or under-supplied human capital moves either in or out in response to changes in wages until the returns from education and training even out with time (Ryoo and Rosen 2004; Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang 2012; Ehrenberg 2004).

As evidence of this equalisation of returns on human capital investments across labour markets, the returns to post-school investments in human capital are similar – 9 to 10 percent – across alternative occupations, and in occupations requiring low and high levels of training, low and high aptitude and for workers with more and less education (Freeman and Hirsch 2001, 2008). There is evidence that workers with similar skills in similarly attractive jobs, occupation and locations earn similar pay (Hirsch 2008; Vermeulen and Ommeren 2009; Rupert and Wasmer 2012; Roback 1982, 1988).

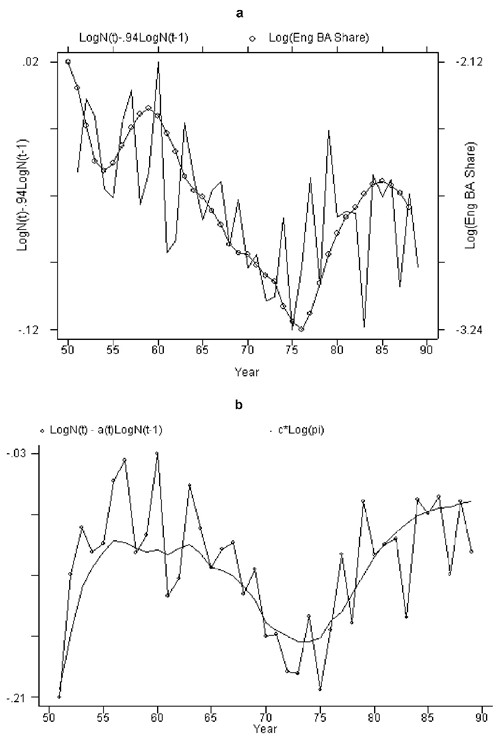

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) found that the labour supply and university enrolment decisions of engineers is “remarkably sensitive” to career earnings prospects. Graduates are the main source of new engineers. Engineers who moved out into other occupations such as management did not often moved back to work again as professional engineers. Ryoo and Rosen (2004) observed when summarising their work that:

Both the wage elasticity of demand for engineers and the elasticity of supply of engineering students to economic prospects are large. The concordance of entry into engineering schools with relative lifetime earnings in the profession is astonishing.

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) found several periods of surplus in the market for engineers. These periods of shortage or surplus corresponded to unexpected demand shocks in the market for engineers such as the end of the Cold War.

Figure 1: New entry flow of engineers: a, actual vs. imputed from changes in stock of engineers; b, time-varying coefficients.

Source: Ryoo and Rosen (2004)

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) noted that importance of permanent versus transitory changes in earnings. Transitory rises and falls in earnings prospects have much less influence on occupational choices and the educational investments of students.

In light of these findings that the supply of engineers rapidly adapted to changing market conditions, Ryoo and Rosen (2004) questioned whether public policy makers have better information on future labour market conditions than labour market participants do. When politicians get worked up about skill shortages, the markets for scientists and engineers often where they make extravagant claims about the ability of the market to adapt to changing conditions because of the long training pipeline involved in university study, including at the graduate level.

There can be unexpected shifts in the supply or demand for particular skills, training or qualifications. These imbalances even themselves out once people have time to learn, update their expectations and adapt to the new market conditions (Rosen 1992; Ryoo and Rosen 2004; Bettinger 2010; Zafar 2011; Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang 2012; Webbink and Hartog 2004).

For example, Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang (2012) found that both expected earnings and students’ abilities in the different majors are important determinants of student’s choice of a college major, and 7.5% of students would switch majors if they made no forecast errors.

The wage premium for a tertiary degree was low and stable in New Zealand in the 1990s (Hylsop and Maré 2009) and 2000s (OECD 2013). This stability in the returns to education suggests that supply has tended to kept up with the demand for skills at least over the longer term at the national level. There were no spikes and crafts that would be the evidence of a lack of foresight among teenagers in choosing what to study.

All in all, the remarkable sensitivity of engineers to a career earnings prospects, the frequent changes of college majors by university students in response to changing economic opportunities, and the stability of the returns on human capital over time suggest that the market for human capital is well functioning.

The argument that the market was not working well was assumed rather than proven. Likewise, the case for additional subsidies for science, technology, engineering and mathematics because of perceived skill shortages has not been made out. There is a large literature showing that the market for professional education works well.

The onus is on those who advocate intervention to come up with hard evidence, rather than innate pessimism about markets that are poorly understood because of a lack of attempts to understand it. Studies dating back to the 1950s by George Stigler and by Armen Alchian found that the market for scientists and engineers works well and the evidence of shortages were more presumed than real.

For those who are job-hunting after the holidays

12 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in job search and matching, personnel economics Tags: search and matching

I find the biggest mistake made at job interviews at the interview panel forget that you are interviewing them as prospective employer.

If they can’t even be polite and friendly to you before you work for them, imagine what they’re like every day.

About 20% of the people I’ve met at job interviews I would never want to work with, much less work for.

Real business cycles, the declining clarity of information and learning by waiting

22 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, entrepreneurship, job search and matching, macroeconomics Tags: real business cycles

Willems and van Wijnbergen (2013) identified reduced clarity in information about business cycle fluctuations as a factor that is the lengthening the lag in the response of employment to output changes in recent US recessions.

Willems and van Wijnbergen (2013) – ungated – found that the trough in employment in the 1991 and 2001 recessions was much later than the troughs for earlier US recessions.

- There was a stronger immediate reduction in employment in pre-1990 US recessions and a faster recovery, so the 1991 and 2001 recessions were initially job-preserving – the rate at which workers were laid off was less than in prior recessions.

- Employment in the 1991 and 2001 recessions continued to fall for another year after the trough in output.

- The job-preserving recessions in 1991 and 2001 were then followed by this delayed recovery in employment growth.

- There is a lengthening labour adjustment lag that slows the loss of jobs at the start of recessions and delays the renewal of recruitment at the end of recessions.

Willems and van Wijnbergen (2013) attributed this combination of job-preserving recessions and delayed employment recoveries in 1991 and 2001 to the interaction of rising labour adjustment costs and a reduction in the clarity of entrepreneurial information about the business cycle.

The rising labour adjustment costs arose from the capital losses to employers of laying off employees who are increasingly rich in firm-specific human capital. The risks of laying off and investing precipitously have increased in recent decades because output growth subsequent to the great moderation in real output growth volatility is less predictable.

The US economy experienced a 50% reduction in volatility for many leading macroeconomic variables as well as low inflation since the early to mid-1980s. Similar declines in the real volatility and inflation rates occurred at about the same time in other industrial countries.

Prior to the mid-1980s, US real output growth was more variable, but this variation was more predictable. Frequent recessions were soon followed by recoveries. Since the early to mid-1980s in the US, major variations in real GDP growth have come increasingly as genuine surprises – 1983–2007 was one long boom punctuated by two mild recessions in 1991 and 2001.

The delay in the official dating of the peaks and troughs in business cycles in the US has increased from an average of 7½ months before 1990 to about 15 months in the post-1990 period (Willems and van Wijnbergen 2013).

With recessions more of a surprise – and the scope and depth of the panic of 2008 is an example of such a surprise in New Zealand and abroad – the value of waiting for better market information has increased.

Less certain information makes it more profitable than before for entrepreneurs to invest in waiting before laying off increasingly human capital-rich employees, making new investments and undertaking fresh recruitment. The impact of the business cycle on employment will be more muted.

Modern recessions can be initially job-preserving – layoffs are postponed for longer because the rising cost of laying off experienced labour is higher and because of the increased value of waiting to see. Recoveries in employment can be more sluggish as investors wait to be sure about the latest trends. These employers can use the employees they hoarded in larger numbers in the downswing to fill orders in the early days of the upswing in business:

We have presented evidence that the lag with which labour input reacts to structural economic shocks went up in the 1980s, thereby bringing jobless recoveries and recessions that were relatively job preserving to the US economy.

Using a real option model, this lagged response is shown to be optimal in a setting where labour input is costly to adjust and where employers are uncertain about the persistence of shocks that drive the business cycle

The role of news in real business cycles

18 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic growth, entrepreneurship, job search and matching, macroeconomics Tags: real business cycles

Revisions in investor beliefs about productivity prospects can partly account for business expansions and contractions. If favourable news about future technological opportunities can seed a boom today in consumption and investment before the actual technological improvement arrives and is realised, news that future productivity growth may not be as good as was previously expected can induce a recession without any actual change in productivity ever occurring.

Investors build in anticipation, starting new projects and recruiting more staff. Their forecasts can turn out to be too optimistic. When entrepreneurial expectations of future productivity are revised, investment demand can fall because of an excess in capital accumulation – recent investments were made under more optimistic beliefs about productivity (Beaudry and Portier 2004).

Investment demand must be muted for a time until the excess capital accumulation is brought into use, refitted or scraped. There also will be layoffs and a lull in recruitment. Job search strategies must also change as job seekers redirect their careers in light of the news about their revised prospects in different firms, industries and competing occupations.

The optimism and pessimism of investors are rational profit-seeking responses to new entrepreneurial knowledge. Profit expectations reflect consumer preferences, resource constraints and technological factors as they exist and are forecast to change and actual and forecasted opportunities and constraints in the investment sector. Entrepreneurs are dynamic risk takers who profit from anticipating shifts in consumer demand, input costs and technology.

Recessions and booms can arise due to the challenges facing entrepreneurs in forecasting the uncertain and ever-changing future demand for new capital that is implied by their forecasts of consumer demand and technological opportunities as Beaudry and Portier (2004) explain:

The view that recession and booms may arise as the result of investment swings generated by agents’ difficulties to properly forecast the economy’s need in terms of capital has a long tradition in economics.

For example, this difficulty was seen by Pigou as being an inherent feature of any economy with technological progress.

As emphasized in Pigou (1926), when agents are optimistic about the future and decide to build up capital in expectation of future demand then, in the case where their expectations are not met, there will be a period of retrenched investment which is likely to cause a recession.

Revisions in entrepreneurial beliefs and investment plans can be required when new information is uncovered (Beaudry and Portier 2004; Sill 2009). There can be lulls in investment demand following these revisions to entrepreneurial forecasts leading to recessions. As Pigou noted in 1927:

The varying expectations of business men … constitute the immediate cause and direct causes or antecedents of industrial fluctuations

Entrepreneurship and sectoral mismatches in labour supply and labour demand

15 Dec 2014 1 Comment

in business cycles, entrepreneurship, job search and matching, macroeconomics Tags: business cycles, Fischer black, mismatch unemployment, sectoral unemployment

An important factor behind business fluctuations arises not from the balance between aggregate output and aggregate consumption, but from the accuracy of entrepreneurial matching of the individual patterns of output with the pattern of actual consumer demand in individual sectors (Black 1987, 1995).

Fluctuations in the match between resource deployment to different sectors and product demand across sectors can create major fluctuations in output and employment because moving resources from one sector into another is costly and time consuming.

What consumers will want and what can be produced in the future is uncertain. A plethora of sectors produce highly differentiated products with increasingly specialised inputs to serve consumers. Modern economic growth is built on ever greater product differentiation, ever greater product variety and ever increasing product quality produced by ever more specialised workers, firms and sectors. This explosion in specialisation is increasing the vulnerability of the business cycle to technology and taste shocks (Black 1987, 1995; Mehrling 2005).

Mismatches in the sectoral pattern of installed production capacity with actual consumer demand will arise because investments are driven by entrepreneurial forecasts of what will be wanted by consumers in the future. The capacity to produce output requires prior investments based on speculations about future consumer tastes, resource availabilities and technology progress. Part of the volatility in output and employment growth is from these investments depending on the uncertain details of the future.

Entrepreneurial errors in forecasting consumer wants will lead to inevitable mismatches of the production capacity with unfolding consumer demand. If future consumer tastes and upcoming technologies were better known now, employment would grow and be reallocated more smoothly to new uses than otherwise (Black 1987, 1995; Mehrling 2005).

When the match between forecasted and realised demand is good, there is a boom. Resources are where consumers want them. When the match is poorer, there is a recession. If events unfold in a markedly unanticipated direction, existing plans, investments and contracts require revision (Black 1987, 1995).

The existing matches between consumer desires, resource allocations by sector and production technologies can deteriorate. While a reallocation occurs, resources are diverted from production and are scrapped or are unemployed while searching for new uses (Black 1987, 1995).

Fixing a deteriorating match requires the structure of production to shift more into line with the structure of consumer demand. This takes time and consumes resources because human and other capital is highly specialised. It takes time for the new investments consistent with the latest entrepreneurial forecasts of consumer demand to be planned, built and start producing (Black 1987, 1995).

What can appear to be cyclical unemployment comes from alternations between periods of above and below average accuracy on entrepreneurial forecasting and better and worse matches in actual consumer demand and actual capacity to supply at the sector level (Black 1987, 1995; Mehrling 2005).

This type of cyclical unemployment is not a product of monetary, fiscal or other policy shocks. Resources need to be reallocated into a better alignment with consumer tastes and technological and resource possibilities. Preventing these sectoral reallocations will keep resources from moving from lower to higher value uses.

After longer booms, more human capital is more specialised to specific sectors, firms and jobs. This increased specialisation that helped underpin the prior economic boom can slow the recovery of employment at the end of the recession.

Job seekers will take longer to find good new job matches if they have more distinct backgrounds and specialised human capital. Job seekers have an incentive to search for longer to find these higher-paid job matches.

Employers will take longer to fill vacancies. The applicant pool is more diverse because of the high degree of specialisation of labour that is a legacy of the long prior boom. This accumulation of specific human capital over the course of longer booms will mean the length of the burden will affect the depth of the subsequent recession.More highly specialised workers have to be re-matched with new occupations and new sectors. More workers than usual will be putting off the day of having to face up to scrapping a significant part of their old human capital.

WH Hutt on job search

14 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in job search and matching, labour economics, macroeconomics, unemployment Tags: job search, search and matching, unemployment, voluntary unemployment

Unemployment, job search, search and matching

Unemployment, job search, search and matching

Sector specific technology and demand shocks and the business cycle

14 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, job search and matching, macroeconomics Tags: natural rate of unemployment, real business cycle, sectoral shocks

New technologies unfold daily, and consumer tastes change with rising incomes and the arrival of new products. Jobs will open in the expanding industries and disappear in the shrinking sectors.

A quarter or more of unemployment rate fluctuations over the business cycle could be due to variations in the rate that labour demand shifts across sectors. These sectoral reallocations in labour demand do not arise from mismatches between entrepreneurial forecasts and actual consumer demand.

The higher unemployment rate is not due to a bunching of technological upgrades in a recession. The above average number of sectoral shifts in labour demand is an independent cause of a temporarily higher natural rate of unemployment.

Lilien (1982) suggested that the amount of labour reallocation can change over time. Some periods may be marked by relatively homogeneous growth in labour demand across sectors, whereas others may be characterized by shifts in the composition of labour demand.

Lilien (1982) provided empirical estimates of the variation in the equilibrium unemployment rate from sectoral reallocation. He concluded that the wide unemployment fluctuations in the 1970s were largely induced by unusual structural shifts in the U.S. economy, which caused the equilibrium unemployment rate to fluctuate by about 3 percentage points over the decade!

An important factor behind business fluctuations arises not from the balance between aggregate output and aggregate consumption, but from the accuracy of entrepreneurial matching of the individual patterns of output with the pattern of actual consumer demand in individual sectors (Black 1987, 1995).

Fluctuations in the match between resource deployment to different sectors and product demand across sectors can create major fluctuations in output and employment because moving resources from one sector into another is costly and time consuming.

To a significant extent, observed fluctuations in the unemployment rate can be fluctuations in the natural rate of unemployment rather than deviations from that natural rate due, for example, to aggregate demand shocks. There will always be some unemployment. There will be new labour force entrants looking for jobs and workers who are between jobs.

The natural rate of unemployment is a long-run level of unemployment that cannot be altered by monetary policy. The natural rate of unemployment depends on the flexibility of wage contracts and labour market institutions, variations in labour demand and supply in individual markets, demographic change, the mobility of workers, unemployment benefits, the cost of gathering information about vacancies and available labour, labour market regulation and random variations in the rate of reallocation of jobs across industries and regions as technology advances and consumer tastes change.

Sectoral shifts in labour demand has a randomness about them because the size, pace and diffusion of technological advances across firms and industries is uneven (Andolfatto and MacDonald 1998, 2004).

The implications of technological progress for jobs has a further randomness because new technologies can displace existing jobs and create new jobs or renovate and update current equipment and employee skills (Mortensen and Pissarides 1998).

As a new technology diffuses, productivity will grow faster in the sectors that are adopting the new technology. During this implementation phase, which is slow, costly and may require considerable learning, there will be reorganisations to capitalise on the impending productivity gains. New technologies differ in the size of the improvement over existing methods and designs and in the difficulty of adopting the new methods. There will be lower growth in years where new technologies offer comparatively minor or less broadly applicable improvements on existing methods. Learning consumes resources, and attempts to learn a new technology through innovation or imitation diverts the resources of firms and workers away from production (Andolfatto and MacDonald 1998, 2004).

This unevenness in the pace and sectoral diffusion of technological progress will introduce unevenness in the rate of labour reallocation across sectors.

With both growing and shrinking sectors, employment may stagnate or fall for a time because the unemployed are searching for new jobs in different industries and perhaps in new occupations or are retraining.

A revival in growth in output and productivity in conjunction with initially poor employment growth is possible and has the attributes of a delayed recovery in employment (Andolfatto and MacDonald 2004).

Cross-sector job searches and the redirection of careers is a longer process than job search in the same industries and occupations. Job migration is more time consuming than the more traditional process of layoffs and rehiring by the same employer or in the same industry and occupation.

During periods of more intensive or above-average sectoral reallocation of labour demand, a mismatch can arise between the skills and experience of the workers who have exited the shrinking sectors and the immediate requirements of the expanding sectors. More workers than average can be moving into new sectors. Some of these job seekers may not be immediately viable candidates for the available jobs and may exert little downward pressure on wages.

There can be mismatch unemployment because the skills and locations of job seekers can be poorly matched with the locations of vacancies. Some local labour markets will have more workers than jobs. Others will have shortages. Job finding can depend on the rate at which the unemployed can retrain or move to locations with unfilled jobs, the rate at which jobs open in different locations and the rate at which workers vacate jobs in places with ready replacements (Shimer 2007).

Cyclical unemployment is a reversible response to lulls in aggregate demand. At the start of a recession, there is a general decline in demand, with few industries creating jobs to replace those that are lost.

As a recession ends, the unemployed are recalled by old employers or find new jobs in those industries as demand renews. Monetary and fiscal policy can aim to smooth these temporary job losses.

Job losses from structural changes in employment and technology are permanent. The sectoral location of jobs has changed. Workers must switch to new industries, sectors and locations or learn new skills.

A role for public policy is to facilitate this process of reallocation to new jobs and retraining.

Critics of the sectoral shifts approach point to the inherent difficulties of distinguishing between sectoral and cyclical movements in unemployment, due to cross-industry differences in sensitivity to aggregate fluctuations.

Recessions as reorganisations

12 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, F.A. Hayek, history of economic thought, job search and matching, macroeconomics, Robert E. Lucas, unemployment Tags: FA Hayek, recessions, recoveries, Robert Lucas

Most models of the shape of recoveries draw on a learning process. A long tradition in business cycle theory holds that limited knowledge of relative price changes can temporarily disrupt labour demand and supply because of errors in wage and price perceptions (Alchian 1969; Sargent 2007; Hellwig 2008).

Pricing, investment and production plans are made on the basis of incomplete and conflicting knowledge of constantly changing aggregate, industry and local conditions. Firms and workers will over- or under-supply when they misperceive wages and prices.

With imprecise information, it takes time for employers and workers to sort out temporary from permanent shifts in demand and supply, inflation-driven changes from real changes in prices and input costs, and general changes from the local changes that may be more important to particular firms. As Hayek explained in his Nobel prize lecture:

The true, though untestable, explanation of extensive unemployment ascribes it to a discrepancy between the distribution of labour (and the other factors of production) between industries (and localities) and the distribution of demand among their products.

This discrepancy is caused by a distortion of the system of relative prices and wages. And it can be corrected only by a change in these relations, that is, by the establishment in each sector of the economy of those prices and wages at which supply will equal demand.

Recoveries are shaped by the speed of entrepreneurial learning about the new labour and product market conditions, the relative cost of adjusting capital and labour rapidly or slowly and the costs and benefits of labour market search. This new learning is necessary because the old constellation of prices and wages is no longer valid.

It was a misdirection of resources brought about by the initial inflationary firm, as Hayek explained in a visit to Australia in 1950:

During a process of expansion the direction of demand is to some extent necessarily different from what it will be after expansion has stopped.

Labour will be attracted to the particular occupations on which the extra expenditure is made in the first instance.

So long as expansion lasts, demand there will always run a step ahead of the consequential rises in demand elsewhere.

And in so far as this temporary stimulus to demand in particular sectors leads to a movement of labour, it may well become the cause of unemployment as soon as the expansion comes to an end…

If the real cause of unemployment is that the distribution of labour does not correspond with the distribution of demand, the only way to create stable conditions of high employment which is not dependent on continued inflation (or physical controls), is to bring about a distribution of labour which matches the manner in which a stable money income will be spent.

This depends of course not only on whether during the process of adaptation the distribution of demand is approximately what it will remain, but ‘also on whether conditions in general are conducive to easy and rapid movements of labour.

In a recession, employers and workers do not immediately know that demand has fallen elsewhere as well as in their own local markets and recognise the need to adjust to their poorer prospects everywhere, and it is not known how long the drop in demand will last (Alchian and Allen 1973).

The cost of learning about available opportunities restricts the speed of a recovery. Workers and entrepreneurs must gather information on the new state of demand and the location and nature of new opportunities. This information is costly and is quickly made obsolete by further changes, and the cost of acquiring information is more costly the faster the information is sought to be acquired (Alchian 1969; Alchian and Allen 1967).

The process of recovering from a recession would be a faster process if the new constellation of wages and prices that are the best alternative uses of resources was known immediately and was credible to firms and workers (Alchian and Allen 1973).

Workers and employers must first have sufficient time to discover what new knowledge they now need to know to serve their interests well, leave enough room for the unforeseeable and keep their knowledge fresh in ever-changing markets.

New wage levels must be created by workers and employers testing and retesting in the labour market the new relative scarcities of labour. Imbalances between the allocation of labour supply and demand to different firms and sectors and the new level and pattern of consumer demand are gradually remedied by changes in relative prices and wages, layoffs, business closures and job search.

Prices are a signal wrapped in an incentive. Growing demand induces higher employment and rising wages. Wages stagnate, and there are layoffs where there is an excess supply.

These changes give the unemployed an incentive to move to new uses and entrepreneurs to profitably hire the unemployed. The ensuing reorganisations are time-consuming and information-intensive because a job seeker and an employer with an apt vacancy take time to find each other.

Prices and wages must change sufficiently for firms to profitably create new jobs. New jobs require time to plan and build new job capital. This is the human, physical and organisational capital underlying a new job. There are also job creation costs when reopening existing positions that were mothballed during the downturn.

How is this to be done? Hayek explained again in 1950 in his speech in Australia:

Full employment policies as at present practised attempt the quick and easy way of giving men employment where they happen to be, while the real problem is to bring about a distribution of labour which makes continuous high employment without artificial stimulus possible.

What this distribution is we can never know beforehand. The only way to find out is to let the unhampered market act under conditions which will bring about a stable equilibrium between demand and supply.

Involuntary unemployment and the great vacation theories of the great depression and Eurosclerosis – updated again

10 Dec 2014 1 Comment

in economic growth, Edward Prescott, Euro crisis, great depression, job search and matching, labour economics, macroeconomics, Robert E. Lucas, unemployment Tags: Eurosclerosis, great depression, voluntary unemployment

Most Keynesian economists are convinced that something exists called involuntary unemployment and people can be unemployed through no fault of their own. They will accept the going wage but no employer is willing to offer it to them.

Lucas and Rapping’s (1969) paper, “Real Wages, Employment, and Inflation” provides the micro-foundations for an analysis of the labour suppl. They felt the need to reconcile the existence of unemployment with market clearing and referred to recent work of Armen Alchian (1969) on search explanations of unemployment.

Lucas and Rapping viewed unemployment as voluntary, including the mass unemployment during the great depression (Lucas and Rapping 1969: 748).

Lucas and-Rapping viewed current labour demand as a negative function of the current real wage. Current labour supply was a positive function of the real wage and the expected real interest rate, but a negative function of the expected future wage.

Under their framework, if workers expect higher real wages in the future or a lower real interest rate, current labour supply would be depressed, employment would fall, unemployment rise, and real wages increase.

Lucas and Rapping depicted labour suppliers as rational optimisers who engaged in inter-temporal substitution: working more when current wages were high relative to expected wages. The prevailing Keynesian approach assumed labour supply was passive, and movements in the demand for labour determined changes in employment.

Lucas and Rapping offered an unemployment equation relating the unemployment rate to actual versus anticipated nominal wages, and actual versus anticipated price levels. Unemployment could be the product of expectational errors about wages.

Lucas and Rapping’s model was poor at explaining unemployment after 1933 in terms of job search and expectational errors.

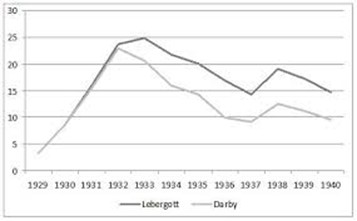

The graph below shows two different series for unemployment in the 1930s in the USA: the official BLS level by Lebergott; and a data series constructed famously by Darby. Darby includes workers in the emergency government labour force as employed – the most important being the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Once these workfare programs are accounted for, the level of U.S. unemployment fell from 22.9% in 1932 to 9.1% in 1937, a reduction of 13.8%. For 1934-1941, the corrected unemployment levels are reduced by two to three-and-a half million people and the unemployment rates by 4 to 7 percentage points after 1933.

Not surprisingly, Darby titled his 1976 Journal of Political Economy article Three-and-a-Half Million U.S. Employees Have Been Mislaid: Or, an Explanation of Unemployment, 1934-1941.

The corrected data by Darby shows stronger movement toward the natural unemployment rate after 1933. Darby concluded that his corrected date are suggests that the unemployment rate was well explained by a job search model such as that by Lucas and Rapping together with the wage fixing under the New Deal that kept real wages up and unemployment high.

Both the Keynesian approach to unemployment and the job search approach to unemployment view workers in emergency government work programs as employed and not as unemployed.

In the late 1970s, Modigliani dismissed the new classical explanation of the U.S. great depression in which the 1930s unemployment was mass voluntary unemployment as follows:

Sargent (1976) has attempted to remedy this fatal flaw by hypothesizing that the persistent and large fluctuations in unemployment reflect merely corresponding swings in the natural rate itself.

In other words, what happened to the U.S. in the 1930’s was a severe attack of contagious laziness!

I can only say that, despite Sargent’s ingenuity, neither I nor, I expect most others at least of the nonMonetarist persuasion,. are quite ready yet. to turn over the field of economic fluctuations to the social psychologist!

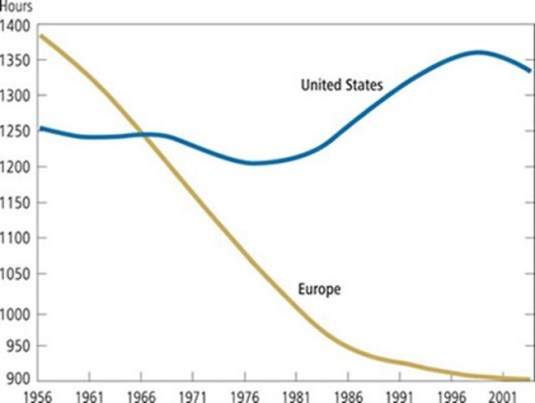

As Prescott has pointed out, the USA in the Great Depression and France since the 1970s both had 30% drops in hours worked per adult. That is why Prescott refers to France’s economy as depressed. The reason for the depressed state of the French (and German) economies is taxes, according to Prescott:

Virtually all of the large differences between U.S. labour supply and those of Germany and France are due to differences in tax systems.

Europeans face higher tax rates than Americans, and European tax rates have risen significantly over the past several decades.

In the 1960s, the number of hours worked was about the same. Since then, the number of hours has stayed level in the United States, while it has declined substantially in Europe. Countries with high tax rates devote less time to market work, but more time to home activities, such as cooking and cleaning. The European services sector is much smaller than in the USA.

Time use studies find that lower hours of market work in Europe is entirely offset by higher hours of home production, implying that Europeans do not enjoy more leisure than Americans despite the widespread impression that they do.

Richard Rogerson, 2007 in “Taxation and market work: is Scandinavia an outlier?” found that how the government spends tax revenues when assessing the effects of tax rates on aggregate hours of market work:

- Different forms of government spending imply different elasticities of hours of work with regard to tax rates;

- While tax rates are highest in Scandinavia, hours worked in Scandinavia are significantly higher than they are in Continental Europe with differences in the form of government spending can potentially account for this pattern; and

- There is a much higher rate of government employment and greater expenditures on child and elderly care in Scandinavia.

Examining how tax revenue is spent is central to understanding labour supply effects:

- If higher taxes fund disability payments which may only be received when not in work, the effect on hours worked is greater relative to a lump-sum transfer; and

- If higher taxes subsidise day care for individuals who work, then the effect on hours of work will be less than under the lump-sum transfer case.

Others such as Blanchard attribute the much lower labour force participation in the EU since the 1970s to their greater preference for leisure in Europe. An increased preference for leisure is another name for voluntary unemployment.

The lower labour force participation in higher unemployment in Europe is voluntary because of the higher demand for leisure among Europeans. According to Blanchard:

The main difference [between the continents] is that Europe has used some of the increase in productivity to increase leisure rather than income, while the U.S. has done the opposite.

An unusual left-right unity ticket emerged to explain the great depression in the 1930s and the depressed EU economies from the 1970s: the great vacation theory.

Explicit and implicit marginal tax rate increases in the past seventy years in the USA

03 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, great recession, job search and matching, labour supply, macroeconomics Tags: Casey Mulligan, great recession, taxation and the labour supply

Recent Comments