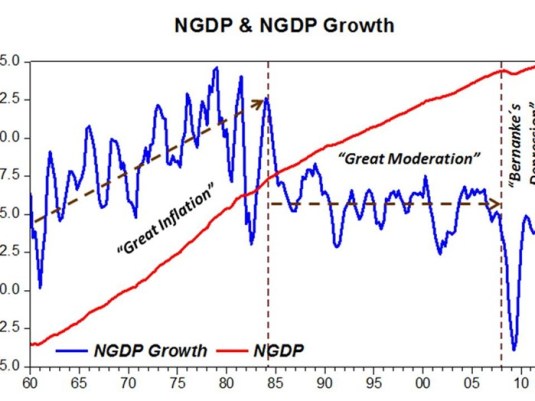

There are large uncertainties about the size and timing of responses to changes in monetary policy. There is a close and regular relationship between the quantity of money and nominal income and prices over the years. However, the same relation is much looser from month to month, quarter to quarter and even year to year. Monetary changes take time to affect the economy and this time delay is itself highly variable. The lags on monetary policy are three in all:

- The lag between the need for action and the recognition of this need (the recognition lag)

-

The lag between recognition and the taking of action (the legislation lag)

-

the lag between action and its effects (the implementation lag)

These delays mean that is it difficult to ascertain whether the effects of monetary policy changes in the recent past have finished taking effect.

Secondly, it is difficult to ascertain when proposed changes in monetary policy will take effect. Thirdly, feedbacks must be assessed. The magnitude of the monetary adjustment necessary to deal with the problem at hand is never obvious.

It is common for a central bank to act incrementally. The central bank makes small adjustments to monetary conditions over time as more information is available on the state of the economy and forecasts are updated.

Most discussions on monetary policy focus on the implementation lag. This lag depends on the fundamental characteristics of the economy.

A long and variable implementation lag means that it is difficult for central banks to ascertain what is happening now or forecast what will happen. Central banks may stimulate the economy after it is well on the way to recovery and tighten monetary policy when the economy is already going into a recession.

In his classic A Program for Monetary Stability, published in 1959, Milton Friedman summarised his empirical findings on length and variability of the lags on monetary policy:

on the average of 18 cycles, peaks in the rate of change in the stock of money tend to preceded peaks in general business by about 16 months and troughs in the rate of change in the stock of money to precede troughs in general business by about 12 months. For individual cycles, the recorded lead has varied between 6 and 29 months at peaks and between 4 and 22 months at troughs.

With lags as variable as those estimated by Friedman, it is difficult to see how any policy maker could know which direction to adjust his policy, much less the precise magnitude needed. Long lags greatly complicate good forecasting. A forecaster cannot know what the state of the economy will be when his policy takes effect.

Many Keynesians, Friedman notes, advocate “leaning against the wind.” By this they mean, in some sense, that the monetary (and fiscal) authorities should try to balance out the private sector’s excesses rather than passively hope that it adjusts on its own.

Friedman tested the Fed’s success at leaning “against the wind” by checking whether the rate of money growth has truly been lower during expansions and higher during contractions. He admits that this method of grading he Fed’s performance is open to criticism, but decides to go ahead and see what turns up. He finds that Fed has – for the periods surveyed – been unsuccessful.

By this criterion, for eight peacetime reference cycles from March 1919 to April 1958. Actual policy was in the ‘right’ direction in 155 months, in the ‘wrong’ direction in 226 months; so actual policy was ‘better’ than the [constant 4% rate of money growth] rule in 41% of the months.

Nor is the objection that the inter-war period biased his study is good since Friedman found that:

For the period after World War II alone, the results were only slightly more favourable to actual policy according to this criterion: policy was in the ‘right’ direction in 71 months, in the ‘wrong’ direct in 79 months, so actual policy was better than the rule in 47% of the months. [2]

One of the best ways to parry a metaphor is with another metaphor. Keynesians have a host of metaphors in their rhetorical arsenal; one frequently voiced is that a wise government should “lean against the wind” when choosing policy. Friedman counters:

We seldom know which way the economic wind is blowing until several months after the event, yet to be effective, we need to know which way the wind is going to be blowing when the measures we take now will be effective, itself a variable date that may be a half year or a year or two from now. Leaning today against next year’s wind is hardly an easy task in the present state of meteorology.

By scrutinising the practice of monetary policy over the decades, Friedman manages to produce objections that both Keynesians and non-Keynesians must take seriously. A key part of any response to Friedman rests on the ability of forecasters to do their jobs with tolerable accuracy.

Recent Comments