Thomas C. Schelling on why international terrorism is so rare

09 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, defence economics, economics of crime, industrial organisation, managerial economics, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics, politics - USA, Thomas Schelling, war and peace Tags: terrorism, Thomas Schelling, war against terror

The epic photos of the ill-fated Ernest Shackleton expedition

25 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in economic history, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: Ernest Shackleton

Impact of Social Sciences – Scientific Misbehavior in Economics: Unacceptable research practice linked to perceived pressure to publish.

23 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

The slow diffusion of modern human resource management

19 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, human capital, industrial organisation, managerial economics, market efficiency, organisational economics, personnel economics, survivor principle Tags: firm size, modern human resource management, technology diffusion, The meaning of competition

Modern human resource management gained ground in the 1980s, slowly replaced the centralising of people management in personnel departments that was widespread by the 1960s.

Modern human resource management stressed rigorous selection and recruitment, more training at induction and on-the-job, more teamwork and multi-skilling, better management-worker communication, the use of quality circles, and encouraging employee suggestions and innovation.

The aim is a highly committed and capable workforce that pulls toward common goals. This drive for employer-employee unity is in contrast to the old days of detachment and formality with managers directing and controlling workers.

Modern human resource management replaced compliance with rules with genuine employee commitment and a unified corporate culture.

Modern human resource management is a technology and there is a long lag on the widespread adoption of any new technology.

The lag on the intra-industry diffusion of new technologies from 10% to 90% of users is 15 to 30 years long (Hall 2003; Grubler 1991). The literature on technology transfer is full of examples of the slow and costly diffusion of new technologies even with the on-site help of the original innovator and experienced consultants (Boldrin and Levine 2008).

New management practices are often complex and they are often slow and costly to introduce successfully without the assistance of consultants with prior experience with the new practices (Bloom and Van Reenen 2007, 2010).

Managerial innovations such as Taylor’s scientific management, Ford’s mass production, Sloan’s M-form corporations, Deming’s quality movement and Toyota’s lean manufacturing diffused slowly over decades. These technologies required large investments in learning, retraining, reorganisation, trial and error and adaptation and there were many failures (Bloom and Van Reenen 2010).

Bryson, Gomez, Kretschmer and Willman (2007) found that workplace voice and modern, high-commitment human resource management practices diffused unevenly across British workplaces. More employees, larger multi-establishment networks, public or for-profit ownership and network effects all increased the rates of diffusion of the new practices.

Large firms may invest more in skills because they are the early adopters of new management practices. Large firms are organisationally complex and they require more structured, explicit management practices to survive. Higher levels of worker skills have been linked with firms having better management practices (Bloom and Van Reenen 2007, 2010).

Employers who pay higher wages lose more if they mismanage or under-utilise well-paid workers. Large firms pay more, on average, so they lose more if they do not adopt good management practices in a timely fashion.

There are fixed costs to adopting new technologies and management practices, so large firms may be the first to find them profitable (Hall 2003). Later adopters may follow this lead when the new practices are more proven and, through experience and adaptation, cheaper to adopt.

The organisational disruption from switching to any new technology can reduce production and profits for several years and the new way of doing business may fail perhaps at a great cost (Holmes, Levine, and Schmitz 2012; Atkeson and Kehoe 2007; Roberts 2004).

These costs and uncertainties slow technology diffusion and explain why smaller firms use seemly out-of-date management practices. The new ways are not yet profitable for them. The pace of adoption of new technologies is driven by changes in the profitability of using the new technology as compared to the old (Karshenas and Stoneman 1993).

Firms of different sizes will invest in skills development and new management practices to the extent that is profitable to their circumstances.

On some occasions, large firms will find it profitable to invest in more skills development because this is part of the costs of investing in more capital per worker. On other occasions, skills development is necessary to reduce the costs of a growing corporate hierarchy.

No firm cannot invest in more skills development unless this growth is buoyed by market demand. Precipitate investments in skills development are fraught with risks.

Why are we always restructuring the workplace? The economics of organisational fickleness

16 Dec 2014 2 Comments

in entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, managerial economics, market efficiency, organisational economics, personnel economics, survivor principle Tags: industrial organisation, survivior principle

Ok, whatever is, is efficient, but I always had my doubts when we are always restructuring wherever I worked. This continual organisational upheaval and restructuring was also a phenomena in the private sector.

What was the survival value of this continual disruption of organisational form and organisational capital in competition with rival firms with more stable internal organisational forms?

Internal reorganisations divert management time away from more profitable pursuits such as facilitating production. Managerial resources are scarce, like any other resource, and must be allocated to their highest value uses.

But as a firm grows, waste accumulates through the duplication of employee effort and the assignment of unnecessary tasks within the organisation.

Jack Nickerson and Todd Zenger wrote a great paper in 2002 on the efficiency of being fickle – of repeated reorganisations of the workplace. Their point was simple: times change and they change a lot faster than we think so organisations have to adapt to their rapidly unfolding new market conditions.

They illustrated their point about the need for regular reorganisation inside a short period of time with a case study of the alternating waves of centralisation and decentralisation in Hewlett-Packard.

Throughout the 1970s, Hewlett-Packard was a thoroughly decentralised organisation and was successful in the market. It had a remarkable record of innovation in the 1970s.

In the early 1980s, Hewlett-Packard hard found this decentralisation was starting to work against it in the rapidly evolving computer market. The Independent divisions developed computers, peripherals and components that will both incompatible with each other and competed with each other.

This redundancy between the independent divisions was costly and was confusing to consumers because they had a hodgepodge of products that really won’t related to each other. The computer industry in the early 1980s was involving very rapidly with many incompatible computers and programs, but the few that turned out to be the best became immensely profitable.

In 1984 and 1985, Hewlett-Packard hard centralise product development in headquarters and put all marketing and sales into one unit. Financial performance recovered after this reorganisation.

By 1990, Hewlett-Packard was on again in a steep financial decline. The centralisation of decision-making has slowed product development and there was a significant drop in innovation.

In 1990, computers was separated into competing products and computing systems. Individual product lines were decentralised and treated a separate business units.

In 1994, Hewlett-Packard again decentralised customer support of all computer activities. Three years later, it decentralised the same activities into three organisations. In 1999 it spun off its instruments and medical business.

Over 16 years, Hewlett-Packard, experience five fundamental ships alternating between decentralisation and centralisation. Each one of these reorganisations was greeted with the share price increase.

The reason why this fickleness in organisational form was efficient was the market changes rapidly. Organisational forms and organisational capital become obsolete rather quickly.

The form of organisation that survives in competition with actual and potential market rivals is that specific form of organisation which allows the firm to deliver the products that customers want at the lowest price while covering costs (Alchian 1950; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b).

Each time Hewlett-Packard decentralised was a time in the product life cycle of their industry where there was rapid innovation. Hewlett-Packard tended to centralise in the consolidation phase of product life cycles.

New technologies are unproven and they come with much less information and prior experience to guide the top of a hierarchy in directing their successful adoption from a distance (Acemoglu, Aghion, Lelarge, Van Reenen and Zilibotti 2007). In any hierarchy, the top faces two problems with their subordinates: communicating their desires and seeing that they are carried out (Tullock 2005).

When a large firm directs major changes from the top of a hierarchy, failures of communication in the chain of command are a growing risk. More employees require more supervisors. More supervisors require more supervisors of supervisors at every tier of the hierarchy – the layers of supervision multiply (Posner 2010; Williamson 1975, 1985).

There are delay in executing orders, a loss of information and feedback on the way up, and the truncation of the directions from the top: there is a general weakening of control and coherence (Posner 2010; Williamson 1975, 1985). The daily implementation problems of new technologies cannot go up and down a hierarchy for resolution.

Firms must decentralise (rather than grow in hierarchy) to profit most from a line manager’s superior local knowledge about the implementation of the latest, more complex technologies. Delegating initiative to managers downstream is vital when a large firm introduces frontier technologies about which information flows upstream are slow and considerable learning by doing and rapid adaptation are required (Acemoglu, Aghion, Lelarge, Van Reenen and Zilibotti 2007; Jensen and Meckling 1995).

New technologies usually bug-ridden and require considerable refinement, adaptation and consumer feedback on their use before the mature product emerges (Greenwood 1999; Greenwood and Yorukoglu 1997). This costly process of learning, improvisation and product and process re-design explains the multi-decade long 10-90 lag in technology diffusion across firms in the same industry and the slow rate of consumer acceptance of new products.

Larger firms may struggle with striking the most profitable balance between greater local managerial discretion and effective corporate governance of a large diverse organisation with professional managers and diffuse ownership structures.

A risk of greater local managerial discretion in a large firm is less effective governance (Williamson 1975, 1985; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b). The risks of separating of ownership from control and the distortions to knowledge flows in hierarchies drives the internal organisation of large firms and the division of decision control and decision management rights between the board and management (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Williamson 1985).

The separation of decision management rights, vested in hired managers, from decision control rights, vested in the board of directors, is a common governance safeguard against conflicts of interest in business, professional and non-profit organisations, large and small (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b).

Decision management rights cover the initiation and the implementation of decisions. Decision control rights involve the ratification and the monitoring of decisions. Managers and division heads carry out the production decisions, budgets and policies on wages, hours, staffing and job designs developed by head office and which are ratified by the board of directors (Fama and Jensen 1983b, 1985).

Competition between different sizes, shapes and internal organisational forms of firms all vying for sales, cheaper sources of supply and investor support sifts out the keener priced, lower cost, and more innovative enterprises (Alchian 1950; Stigler 1958). These lower-cost firms will be able to under-sell their higher cost rivals.

The winning firm size and internal organisational shape is that configuration which meets any and all problems the firm is actually facing and seizes more of the entrepreneurial opportunities that are within its grasp (Stigler 1958; Alchian 1950).

Large firms invest heavily in mimicking the nimbleness of small firms. Some firms re-create some of the advantages of being small by organising into M-form hierarchies made up of product divisions to improve performance monitoring, identify managerial slack, encourage mutual monitoring, promote competition within the firm for top-level management positions and facilitate comparisons of compliance with the policies of head office (Klein 1999; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Williamson 1975, 1985).

Large firms must develop organisational architectures to assign decision rights, reward employees, and evaluate the performance of employees and business units. The aim is to empower subordinates with the requisite local knowledge with the power to act swiftly and the incentive to make good decisions. The organisational architecture of a firm encompasses the assignment of decision rights within the firm, the methods of rewarding individual employees, and the structure of the systems that evaluate the performance of individual employees and business units.

Poor cost control, budgetary excess and any lack of innovation and initiative over products designs and pricing, input mixes and wage and employment policies will reflect in relative divisional performances and overall corporate profits.

Any news of less promising current and future net cash flows will feed into share prices and into the labour market prospects of both career managers and the members of boards of directors (Manne 1965; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Demsetz 1983; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). To survive, managerial firms must balance delegation with more centralised control (Fama and Jensen 1983a; McKenzie and Lee 1998).

One way of balancing delegation with centralised control is simply to reorganise the firm on a regular basis as market circumstances change and entrepreneurial judgements about the future are updated. This regular reorganisation of the firm may seem fickle, but the firm must adapt or die. Firms must be efficiently fickle in their organisational forms.

Not only is whatever is, is efficient, any attempt to change whatever is, is efficient, because otherwise it wouldn’t be attempted. Of course, these reorganisations are entrepreneurial ventures that are never guaranteed success.

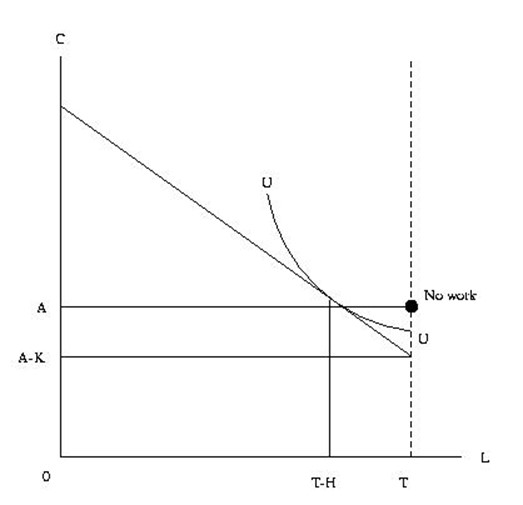

The trade-off between hiring higher-skilled and less-skilled workers

13 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in industrial organisation, labour economics, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: demand for labour, derived demand for labour, profit-maximisation

Firms differ in the skill compositions of their labour forces because higher-skilled labour is not always the most profitable type of labour to hire.

A profit-minded firm seeks low costs per unit of labour. In truth, nothing is expensive or cheap. This is because buyers will keep buying until the marginal cost equals the marginal benefit. The next unit was not purchased because it wasn’t worth the cost. The last unit was bought because its cost just matched its benefit.

The most cost-effective labour is the labour with the lowest ratio of wages to output. Low cost per unit of output is the goal whether it is comes from low wages or high labour productivity (Lazear 1998).

The wage spread between high quality and lower quality workers is large enough such that no employer hiring lower quality workers can profitably switch to hire higher quality recruits and no firms hiring high-quality workers will switch to hire lower quality recruits (Lazear 1998).

Employers will buy more of an under-priced skill until the returns to labour equalise again across different skill levels and the hiring of any more of the hitherto mispriced skill is no longer profitable because of rising wages.

Firms of all sizes will revisit their skills strategies when market conditions change if they hope to survive in their new circumstances.

Comparing sea ice today to Shackleton’s Ill Fated Voyage – 100 years ago this month

12 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in economic history, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: Ernest Shackleton

I am a great admirer of Ernest Shackleton – his unlimited determination and boundless courage

What is the main driver of a gender wage gap?

12 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, discrimination, gender, labour economics, liberalism, organisational economics, personnel economics

Some economics of zero hours contracts – part 4: team production as a constraint on working time flexibility

07 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics, unions Tags: labour economics, zero hours contracts

To continue with my theme in my previous three blogs that zero hours contracts aren’t supposed to exist, a leading explanation for the hesitancy of employers to agree to part-time hours is team production (Hutchens and Grace-Martin 2004, 2006; Hutchens 2010).

Employers may want their employees to work a minimum number of working hours because of rigid production technologies and/or team production. Production technologies vary in the rigidity they impose on the hours worked by employees.

The co-ordination of working times is paramount to effective team production. Once the work time schedule is fixed for team, the worker faces a choice between working at the fixed schedule or working in another team or job.

Two common examples of teams are an assembly line and a football team. Both require a minimum number of workers with rigid starting and finishing times. The absence of a team member could reduce team productivity or safety or even stop production entirely.

When the cost of absence is higher such as for team production, there are more efforts to reduce absences. When a single employee absence is costly to employers, employers take steps to ensure that a minimum number of workers plus a reserve are present. There will be increased spending on monitoring, more cross-training, mutual monitoring by employees and the use of peer pressure. Multiple production lines reduce the risks of absence because spare staff can be hired to fill in across different teams.

Other workers can produce independently of their co-workers. One example is a member of a typing pool. The contribution of each typist depends on their efforts alone. The increment they add to production does not vary with the presence or absence of others, nor is the productivity of others affected by their output. If there is little teamwork, the absence of a worker does not affect other workers.

The Department of Labour (2009) found that about 60 per cent of New Zealand full-time employees did not have flexible hours.

A leading reason for employers hiring part-time workers is to solve scheduling problems that arise when hours of operation and peak periods of daily or weekly production do not easily divide into standard shift lengths.

For example, within the day and within the week variation in customer demand explains the heavy use of part-timers in restaurants, retails stores and many services outlets. Not surprisingly, zero hours contracts arise in industries such as the food services sector where there is already a long history of part-time work.

Different production technologies require their own levels of coordination and supervision. This complicates the use of part-timers. Scheduling problems can arise of workers arrive at different times.

A mix of full and part-time employees could increase supervision costs. There can be repetitions of instructions and different capabilities to perform the same tasks.

Two part-timers could be productive if job is repetitive and does not require much co-ordination. Again, and not surprisingly, zero hours contracts occur in industries where the jobs appear to be relatively simple and the worker can pretty much work out what to do after a little bit of training with little supervision.

A managerial employee is less likely to be allowed to be part-time because they will be absent when employees need direction (Hutchens and Grace-Martin 2004, 2006. Managerial employees have scale effects. Higher level management decisions percolate through the rest of the organisation. The interaction of talent and scale ensures that the impact of any loss of efficiency from having part-time managers compound geometrically into the efforts and productivity of those they lead. Sharing a managerial job has costs because information must be exchanged and a common agenda agreed.

The economics of team production suggests that zero hours contracts will occur in teams with peaks and ebbs in customer demand, where workers are pretty much interchangeable alone can take over with little or no instructional briefing, and the level of task dependency between workers is small.

When extra workers on zero hours contracts are brought on to deal with the spike in demand, they take over the servicing of this demand. There is little need for them to interact with existing workers. For example, in a restaurant situation, they could deal with the extra tables filled by the spike in demand. In a McDonald’s restaurant, for example, they could just take over that the till that was otherwise not in use and serve the extra queues of customers.

To summarise, unless we have a good idea about why firms are moving to zero hours contracts, which we don’t, and why employees sign these contracts rather than work for other employers who offer more regular hours of work, meddling in these still novel arrangements is pretty risky.

Recent Comments