Figure 1: Tax revenue as percentage of French, German, British and US GDP, 1965–2013

Source: OECD StatExtract.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

28 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, politics - USA, public economics, taxation Tags: British economy, France, Germany, growth of government

Figure 1: Tax revenue as percentage of French, German, British and US GDP, 1965–2013

Source: OECD StatExtract.

18 May 2015 Leave a comment

in politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: company tax, endogenous growth theory, foreign direct investment, lost decades

New Zealand is one of only two developed countries, the other being Finland, that switched from a territorial tax system to a worldwide system.Both eventually returned to a territorial tax system for competitiveness reasons. New Zealand went one step further in their experiment with worldwide taxation by ending deferral.

This resulted in a twenty year stagnation in foreign investment at a time when foreign investment was growing dramatically in the rest of the developed world.

This coincided with an economic decline in New Zealand relative to Australia and the rest of the developed world. Because foreign investment is key to accessing the world’s consumers, it is not surprising that less foreign investment translated to less economic prosperity at home.

The New Zealand experience shows that ending or limiting deferral in the United States, as President Obama and others have proposed, would likely have severe economic downsides. Instead, as New Zealand eventually did in 2009, the U.S. should implement a territorial system that exempts foreign earnings.

via New Zealand’s Experience with Territorial Taxation | Tax Foundation.

14 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of regulation, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking, urban economics Tags: Auckland, capital gains tax, housing affordability, RMA

If the affordability crisis in New Zealand is demand side driven requiring capital gains tax to temper that demand, why is the affordability crisis so marked in one city? Does that make a case for a capital gains tax only on Auckland or suggest the capital gains tax is trying to solve the wrong problem.

via demographia.com

14 May 2015 Leave a comment

in politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics, taxation Tags: efficient taxes, tax reform

12 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economic growth, economic history, great depression, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics, taxation Tags: Edward Prescott, Euroclerosis, France, Germany, labour supply, Robert Lucas, taxation and labour supply

Figure 1 shows that Americans work the same hours per year pretty much the entire post-war period. By contrast, there is been a long decline in hours worked in Germany and France. The large drop in 1992 was German unification.

Figure 1: annual hours worked per working age American, German and French, 1950 – 2013

Source: OECD StatExtract and The Conference Board Total Economy Database™,January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/

The long decline seemed to tally with the disproportionately sharp rise in the average tax rate on labour income, including social security contributions in France and Germany. When tax rates on labour income, including social security contributions stabilised in about 1980, hours worked stabilised in all countries.

Figure 2: average tax rate on labour income,USA, Germany and France, 1950 – 2013

Source: Source: Cara McDaniel.

Some pander to the great vacation theory of European labour supply. This is the hypothesis of a large increase in the preference for leisure in the European Union member states. That is, mass voluntary unemployment and mass voluntary reductions and labour supply by choice by Europeans. They just decided to work less.

This is not the first outing for the great vacation theory of labour supply. In the late 1970s, Modigliani dismissed the new classical explanation of Lucas and Rapping (1969) of the U.S. great depression in which the 1930s unemployment was voluntary unemployment – the great depression was just a great vacation – with the following remarks:

Sargent (1976) has attempted to remedy this fatal flaw by hypothesizing that the persistent and large fluctuations in unemployment reflect merely corresponding swings in the natural rate itself.

In other words, what happened to the U.S. in the 1930’s was a severe attack of contagious laziness!

I can only say that, despite Sargent’s ingenuity, neither I nor, I expect most others at least of the non-Monetarist persuasion, are quite ready yet. to turn over the field of economic fluctuations to the social psychologist!

As Prescott has pointed out, the USA in the Great Depression and France since the 1970s both had 30% drops in hours worked per adult. That is why Prescott refers to France’s economy as depressed. The reason for the depressed state of the French (and German) economies is taxes, according to Prescott:

Virtually all of the large differences between U.S. labour supply and those of Germany and France are due to differences in tax systems.

Europeans face higher tax rates than Americans, and European tax rates have risen significantly over the past several decades.

Countries with high tax rates devote less time to market work, but more time to home activities, such as cooking and cleaning. The European services sector is much smaller than in the USA.

Time use studies find that lower hours of market work in Europe is entirely offset by higher hours of home production, implying that Europeans do not enjoy more leisure than Americans despite the widespread impression that they do. Europeans did not work less. They worked more on activities that were not taxed.

11 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: company tax rates, foreign investment, multinational corporations, tax competition

How Taxes Affect Investment Decisions For Multinational Firms onforb.es/1Oe5lKu by @ErikCederwall http://t.co/BduZZbHs2n—

Tax Foundation (@taxfoundation) April 15, 2015

03 May 2015 2 Comments

in economic growth, economic history, entrepreneurship, macroeconomics, Public Choice, public economics Tags: British disease, British economy, Margaret Thatcher, poor man of Europe, Sweden, Swedosclerosis, taxation and the labour supply, welfare state

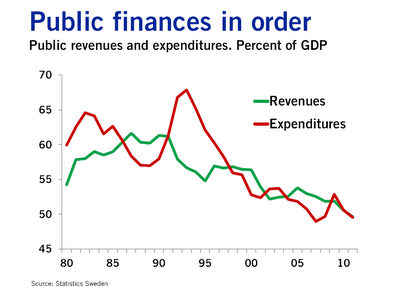

In 1970, Sweden was labelled as the closest thing we could get to Utopia. Both the welfare state and rapid economic growth – twice as fast as the USA for the previous 100 years.

Of course the welfare state was more of a recent invention. Assar Lindbeck has shown time and again in the Journal of Economic Literature and elsewhere that Sweden became a rich country before its highly generous welfare-state arrangements were created

Sweden moved toward a welfare state in the 1960s, when government spending was about equal to that in the United States – less that 30% of GDP.

Sweden could afford to expand its welfare state at the end of the era that Lindbeck labelled ‘the period of decentralization and small government’. Swedes in the 60s had the third-highest OECD per capita income, almost equal to the USA in the late 1960s, but higher levels of income inequality than the USA.

By the late 1980s, Swedish government spending had grown from 30% of gross domestic product to more than 60% of GDP. Swedish marginal income tax rates hit 65-75% for most full-time employees as compared to about 40% in 1960. What happened to the the Swedish economic miracle when the welfare state arrived?

In the 1950s, Britain was also growing quickly, so much so that the Prime Minister of the time campaigned on the slogan you never had it so good.

By the 1970s, and two spells of labour governments, Britain was the sick man of Europe culminating with the Winter of Discontent of 1978–1979. What happened?

Sweden and Britain in the mid-20th century are classic examples of Director’s Law of Public Expenditure. Once a country becomes rich because of capitalism, politicians look for ways to redistribute more of this new found wealth. What actually happened to the Swedish and British growth performance since 1950 relative to the USA as the welfare state grew?

Figure 1: Real GDP per Swede, British and American aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1950-2013, $US

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 1 is not all that informative other than to show that there is a period of time in which Sweden was catching up with the USA quite rapidly in the 1960s. That then stopped in the 1970s to the late 1980s. The rise of the Swedish welfare state managed to turn Sweden into the country that was catching up to be as rich as the USA to a country that was becoming as poor as Britain.

Figure 2: Real GDP per Swede, British and American aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, detrended, 1.9%, 1950-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 2 which detrends British and Swedish growth since 1950 by 1.9% is much more informative. The US is included as the measure of the global technological frontier growing at trend rate of 1.9% in the 20th century. A flat line indicates growth at 1.9% for that year. A rising line in figure 2 means above-trend growth; a falling line means below trend growth for that year. Figure 2 shows the USA growing more or less steadily for the entire post-war period. There were occasional ups and downs with no enduring departures from trend growth 1.9% until the onset of Obamanomics.

Figure 2 illustrates the volatility of Swedish post-war growth. There was rapid growth up until 1970 as the Swedes converged on the living standards of Americans. This growth dividend was then completely dissipated.

Swedosclerosis set in with a cumulative 20% drop against trend growth. The Swedish economy was in something of a depression between 1970 and 1990. Swedish economists named the subsequent economic stagnation Swedosclerosis:

Prescott’s definition of a depression is when the economy is significantly below trend, the economy is in a depression. A great depression is a depression that is deep, rapid and enduring:

There is no significant recovery during the period in the sense that there is no subperiod of a decade or longer in which the growth of output per working age person returns to rates of 2 percent or better.

The Swedish economy was not in a great depression between 1970 and 1990 but it meets some of the criteria for a depression but for the period of trend growth between1980 and 1986.

Between 1970 and 1980, output per working age Swede fell to 10% below trend. This happened again in the late 80s to the mid-90s to take Sweden 20% below trend over a period of 25 years.

Some of this lost ground was recovered after 1990 after tax and other reforms were implemented by a right-wing government. The Swedish economic reforms from after 1990 economic crisis and depression are an example of a political system converging onto more efficient modes of income redistribution as the deadweight losses of taxes on working and investing and subsidies for not working both grew.

The Swedish economy since 1950 experienced three quite distinct phases with clear structural breaks because of productivity shocks. There was rapid growth up until 1970; 20 years of decline – Swedosclerosis; then a rebound again under more liberal economic policies.

The sick man of Europe actually did better than Sweden over the decades since 1970. The British disease resulted in a 10% drop in output relative to trend in the 1970s, which counts as a depression.

There was then a strong recovery through the early-1980s with above trend growth from the early 1980s until 2006 with one recession in between in 1990. So much for the curse of Thatchernomics?

After falling behind for most of the post-war period, the UK had a better performance compared with other leading countries after the 1970s.

This continues to be true even when we include the Great Recession years post-2008. Part of this improvement was in the jobs market (that is, more people in work as a proportion of the working-age population), but another important aspect was improvements in productivity…

Contrary to what many commentators have been writing, UK performance since 1979 is still impressive even taking the crisis into consideration. Indeed, the increase in unemployment has been far more modest than we would have expected. The supply-side reforms were not an illusion.

John van Reenen goes on to explain what these supply-side reforms were:

These include increases in product-market competition through the withdrawal of industrial subsidies, a movement to effective competition in many privatised sectors with independent regulators, a strengthening of competition policy and our membership of the EU’s internal market.

There were also increases in labour-market flexibility through improving job search for those on benefits, reducing replacement rates, increasing in-work benefits and restricting union power.

And there was a sustained expansion of the higher-education system: the share of working-age adults with a university degree rose from 5% in 1980 to 14% in 1996 and 31% in 2011, a faster increase than in France, Germany or the US. The combination of these policies helped the UK to bridge the GDP-per-capita gap with other leading nations.

01 May 2015 Leave a comment

in politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics Tags: Director's Law, laffer curve

01 May 2015 Leave a comment

in politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: average tax rates, Marginal tax rates, vaccination and the labour supply

Highest income #tax rate among #OECD countries? Belgium with 42.8% statista.com/chart/3337/whe… http://t.co/RgaWxsGPzB—

Statista (@StatistaCharts) March 25, 2015

30 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, income redistribution, Public Choice, public economics Tags: capital of freedom, entrepreneurial alertness, neoliberalism, top 1%

29 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in income redistribution, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking Tags: public sector transparency

Tax summary: here's another honest/informative version of @hmtreasury chart by @StrongerInNos that explains "welfare" http://t.co/SeH9FJIRWq—

Jonathan Portes (@jdportes) November 02, 2014

28 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics Tags: conspiracy theories, Leftover Left, neoliberalism, taxation in the labour supply, top 1%

How much does each income group pay in taxes? bit.ly/1JHSCik by @aplundeen http://t.co/B66ynsUrkc—

Tax Foundation (@taxfoundation) April 14, 2015

The U.S. Income Tax system is progressive bit.ly/1FG9Usm by @aplundeen http://t.co/HXDWbvv1xy—

Tax Foundation (@taxfoundation) April 15, 2015

24 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in income redistribution, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics Tags: Director's Law, Leftover Left, median voter theorem, neoliberalism, tax reform, welfare state

24 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, fiscal policy, great depression, macroeconomics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: capital taxation, New Zealand, taxation and the labour supply, top tax rate

Source: Ellen McGrattan.

There were large differences in increases in the 1930s in the top marginal income tax rate between Sweden, the UK, France with Australia and New Zealand and between the USA and Canada and the rest as McGrattan explains:

These data show that there is a strong negative correlation, roughly −94%, between the change in the top income tax rates and the deviation in per capita real GDP relative to trend in 1933.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments