There are at least 98 regulated occupations in New Zealand covering about 20% of the workforce. In 2011, this amounts to 440,371 workers. The skills that are regulated range across all skill sets and many occupations:

- 49% of regulation is in the form of a licence;

- 18% of regulated work is in the form of licensing of tasks;

- 31% of regulated workers require a certificate; and

- 4% of regulated workers require registration.

There are 32 different governing Acts that regulated occupations in New Zealand with 55% of the workers subject to occupational regulation are employed in just five occupations:

- 98,000 teachers;

- 48,500 nurses;

- 42,730 bar managers;

- 32,733 chartered accountants; and

- 22,749 electricians.

The Health Practitioners Competency Assurance Act 2003 regulates 22 occupations and a total of 89,807 workers. The next best is the 10 occupations regulated by the Health and Safety in Employment Act 2002 which regulates an unknown number of occupations. The Civil Aviation Act 1990 regulates eight occupations and 19,095 workers, the Building Act 2004 regulates seven occupations and 21,101 workers and the Maritime Transport Act 1994 regulates six occupations and 20,500 workers. 12 of the regulated occupations are regulated under laws passed since 2007.

The purpose of occupational regulation is to protect buyers from quacks and lemons – to overcome asymmetric information about the quality of the provider of the service.

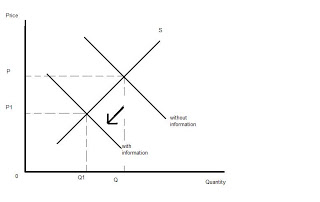

Adverse selection occurs when the seller knows more than the buyer about the true quality of the product or service on offer. This can make it difficult for the two people to do business together. Buyers cannot tell the good from the bad products on offer so many they do not buy to all and withdraw from the market.

Goods and services divide into inspection, experience and credence goods.

- Inspection goods are goods or services was quality can be determined before purchase price inspecting them;

- Experience goods are goods whose quality is determined after purchase in the course of consuming them; and

- Credence goods are goods whose quality may never be known for sure as to whether the good or service actually worked – was that car repair or medical procedure really necessary?

The problem of adverse selection over experience and credence goods present many potentially profitable but as yet unconsummated wealth-creating transactions because of the uncertainty about quality and reliability.

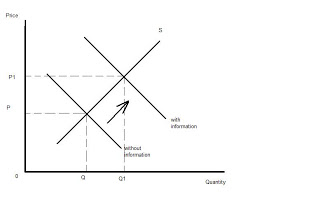

Buyers are reluctant to buy if they are unsure of quality, but if such assurances can be given in a credible manner, a significant increase in demand is possible.

Any entrepreneur who finds ways of providing credible assurances of the quality of this service or work stands to profit handsomely. Brand names and warranties are examples of market generated institutions that overcome these information gaps through screening and signalling.

Screening is the less informed party’s effort, usually the buyer, to learn the information that the more informed party has. Successful screens have the characteristic that it is unprofitable for bad types of sellers to mimic the behaviour of good types.

Signalling is an informed party’s effort, usually the seller, to communicate information to the less informed party.

The main issue with quacks in the labour market is whether there are a large cost of less than average quality service, and is there a sub-market who will buy less than average quality products in the presence of competing sellers competing on the basis of quality assurance. This demand for assurance creates opportunities for entrepreneurs to profit by providing assurance.

David Friedman wrote a paper about contract enforcement in cyberspace where the buyer and seller is in different countries so conventional mechanisms such as the courts are futile in cases where the quality of the good is not as promised or there is a failure to deliver at all:

Public enforcement of contracts between parties in different countries is more costly and uncertain than public enforcement within a single jurisdiction.

Furthermore, in a world where geographical lines are invisible, parties to publicly enforced contracts will frequently not know what law those contracts are likely to fall under. Hence public enforcement, while still possible for future online contracts, will be less workable than for the realspace contracts of the past.

A second and perhaps more serious problem may arise in the future as a result of technological developments that already exist and are now going into common use. These technologies, of which the most fundamental is public key encryption, make possible an online world where many people do business anonymously, with reputations attached to their cyberspace, not their realspace, identities

Online auction and sales sites address adverse selection with authentication and escrow services, insurance, and on-line reputations through the rating of sellers by buyers.

E-commerce is flourishing despite been supposedly plagued by adverse selection and weak contract enforcement against overseas venders.

In the labour market, screening and signalling take the form of probationary periods, promotion ladders, promotion tournaments, incentive pay and the back loading of pay in the form of pension investing and other prizes and bonds for good performance over a long period.

In the case of the labour force, there are good arguments that a major reason for investments in education is as a to signal quality, reliability, diligence as well as investment in a credential that is of no value the case of misconduct or incompetence. Lower quality workers will find it very difficult if not impossible to fake quality and reliability in this way – through investing in higher education.

In the case of teacher registration, for example, does a teacher registration system screen out any more low quality candidates for recruitment than do proper reference checks and a police check for a criminal record.

Mostly disciplinary investigations and deregistrations under the auspices of occupational regulation is for gross misconduct and criminal convictions rather than just shading of quality.

Much of personnel and organisational economics is about the screening and sorting of applicants, recruits and workers by quality and the assurance of performance.

Alert entrepreneurs have every incentive to find more profitable ways to manage the quality of their workforce and sort their recruitment pools.

Baron and Kreps (1999) developed the recruitment taxonomy made up of stars, guardians and foot-soldiers.

Stars hold jobs with limited downside risk but high performance is very good for the firm – the costs of hiring errors for stars such as an R&D worker are small: mostly their salary. Foot-soldiers are employees with narrow ranges of good and bad possible outcomes.

Guardians have jobs where bad performance can be a calamity but good job performance is only slightly better than an average performance.

Airline pilots and safety, compliance, finance and controller jobs are all examples of guardian jobs where risk is all downside. Bad performance of these jobs can bring the company down. Dual control is common in guardian jobs.

The employer’s focus when recruiting and supervising guardians is low job performance and not associating rewards and promotions with risky behaviours. Employers will closely screen applicants for guardian jobs, impose long apprenticeships and may limit recruiting to port-of-entry jobs.

The private sector has ample experience in handling risk in recruitment for guardian jobs. Firms and entrepreneurs are subject to a hard budget constraints that apply immediately if they hire quacks and duds.

Blackboard economics says that governments may be able to improve on market performance but as Coase warned that actually implement regulatory changes in real life is another matter:

The policy under consideration is one which is implemented on the blackboard.

All the information needed is assumed to be available and the teacher plays all the parts. He fixes prices, imposes taxes, and distributes subsidies (on the blackboard) to promote the general welfare.

But there is no counterpart to the teacher within the real economic system

Occupational regulation comes with the real risk of the regulation turning into an anti-competitive barrier to entry as Milton Friedman (1962) warned:

The most obvious social cost is that any one of these measures, whether it be registration, certification, or licensure, almost inevitably becomes a tool in the hands of a special producer group to obtain a monopoly position at the expense of the rest of the public.

There is no way to avoid this result. One can devise one or another set of procedural controls designed to avert this outcome, but none is likely to overcome the problem that arises out of the greater concentration of producer than of consumer interest.

The people who are most concerned with any such arrangement, who will press most for its enforcement and be most concerned with its administration, will be the people in the particular occupation or trade involved.

They will inevitably press for the extension of registration to certification and of certification to licensure. Once licensure is attained, the people who might develop an interest in undermining the regulations are kept from exerting their influence. They don’t get a license, must therefore go into other occupations, and will lose interest.

The result is invariably control over entry by members of the occupation itself and hence the establishment of a monopoly position.

Friedman’s PhD was published in 1945 as Income from Independent Professional Practice. With co-author Simon Kuznets, he argued that licensing procedures limited entry into the medical profession allowing doctors to charge higher fees than if competition were more open.

Data Source: Martin Jenkins 2012, Review of Occupational Regulation, released by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment under the Official Information Act.

Recent Comments