A rising majority of university students around the world are women (HT @cblatts) http://t.co/6loTmSgrk9—

William Easterly (@bill_easterly) June 15, 2015

A rising majority of university students around the world are women

26 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, discrimination, economic history, economics of education, gender, growth disasters, growth miracles, human capital, labour economics Tags: College premium, compensating differentials, education premium, graduate premium, marriage and divorce, reversing gender gap

South Korean gender pay gap for the 10th, 50th and 90th percentile since 1985

24 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, discrimination, economic history, economics of education, gender, growth miracles, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, compensating differentials, gender wage gap, marital division of labour, South Korea

The Japanese gender pay gap at the 10th, 50th and 90th percentile since 1975

23 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economic history, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: compensating differentials, gender wage gap, Japan

The unadjusted gender pay gap is still large in Japan but is declining slowly.

Has the gender gap closed for graduates over the last generation? @greencatherine

19 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of education, gender, human capital, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, compensating differentials, economics of fertility, gender wage gap, marriage and divorce, reversing gender gap

Today’s women who are well-established in their careers in their 30s and 40s are doing better than their mothers who are also tertiary educated in terms of closing the gender wage gap. The gender wage gap in the chart below is unadjusted. It is the raw gender wage gap for women aged 35 to 44 and for women aged 55 to 64.

In Canada and the USA there is been no progress at all. In New Zealand, the gender gap between male and female tertiary educated workers is a little larger for today’s prime age women graduates than for older female workers who completed a tertiary education.

I suspect that gender gap be no smaller for today’s career women as compared to two decades ago has something to do with compensating differentials.

Today’s career women want it all: both motherhood and a career. They trade-off work-life balance for wages.

Women choose university degrees and occupations that are more agreeable to a balancing motherhood and a career.

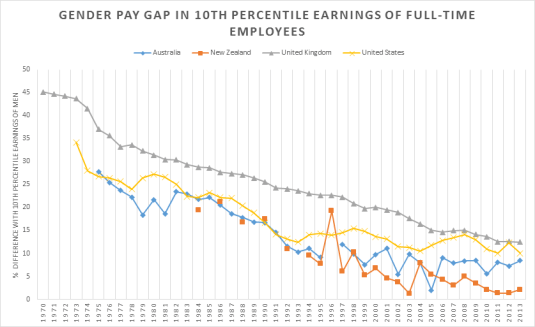

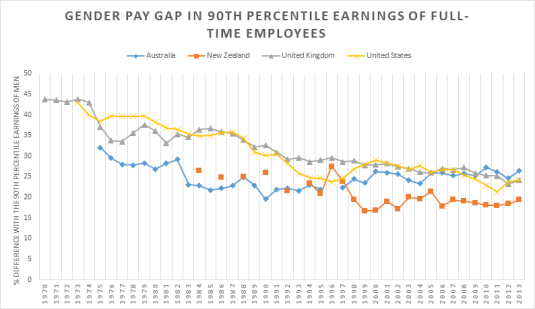

@janlogie The dramatic closing of the gender pay gap at the 10th percentile in the US, UK, Australia and NZ since 1970 but not at the 90th percentile!

15 Oct 2015 4 Comments

in discrimination, economic history, gender, human capital, labour economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, compensating differentials, gender wage gap, marriage and divorce

It seems that the top 10% of men are so busy oppressing the top 10% of women that they forgot to keep up the violence inherent in the capitalist system against the bottom 10% of women. The gender pay gap at the bottom of the economic strata closed quite dramatically and consistently since 1970 or as far back as data was available in Australia, New Zealand, the UK and USA. Much of the closing of the gender pay gap for the low-paid was under the scourge of Reagan, Thatcher, Hawke and Keating and Rogernomics.

Source and Notes: OECD Employment Database. The gender gap plotted below is unadjusted. It is calculated as the difference between the 10th percentile earnings of men and the 10th percentile earnings of women relative to the 10th percentile earnings of men. Estimates of earnings used in the calculations refer to gross earnings of full-time wage and salary workers. However, this definition may slightly vary from one country to another.

By comparison to this dramatic liberation of women from the gender pay gap at the bottom, the gender pay gap for full-time employees has not really tapered down that much at the top of the income distribution and has been pretty flat for coming on 20 years. It seems the class war is over and has been won by women at the bottom but not at the top?

Younger, more educated women delay having families and can earn as much as their partners. bit.ly/1jw98Ky http://t.co/BaDIlBIBA2—

Ninja Economics (@NinjaEconomics) October 14, 2015

Rather than up the workers, the battle cry of the Posh Trots is up the managers, liberate them from insidious pay inequities imposed upon them by a vast sexist conspiracy of male managers.

Source and Notes: OECD Employment Database. The gender gap plotted below is unadjusted. It is calculated as the difference between the 10th percentile earnings of men and the 10th percentile earnings of women relative to the 10th percentile earnings of men. Estimates of earnings used in the calculations refer to gross earnings of full-time wage and salary workers. However, this definition may slightly vary from one country to another.

This failure to close the gender pay gap at the top requires more investigation. The available of reliable contraceptives in the late 1960s led to an explosion of investment by women in long duration professional education and in careers where absences because of motherhood in their 20s and 30s was penalised in terms of human capital depreciation and promotional opportunities.

The reason for the endurance of the gender pay gap at the top of the income distribution is compensating differentials. Women at the top were able to have it all.

Professional women could invest in a career and a family and mix-and-match according to their own preferences for career and family and timing of births rather than the preferences of others who looked upon them as some sort of pathfinder for their gender. It is at the top of the income distribution where short absences from the workplace can has very large consequences for wages and promotion.

Are you happy in your job?

12 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in occupational choice Tags: compensating differentials

Is sociology really irrelevant in policy debates?

03 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economics of bureaucracy, economics of media and culture, income redistribution, labour economics, occupational choice, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: compensating differentials, evidence-based policy, media bias, offsetting behaviour, public intellectuals, sociology, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

Is sociology really irrelevant in policy debates? @familyunequal does a better job with the #s blog.contexts.org/2015/01/25/soc… http://t.co/c4E25DTCmm—

(@SocImages) February 04, 2015

@NZGreens @TransportBlog cars rule in Auckland! Auckland commuting times by transport mode

21 Aug 2015 1 Comment

in job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice, politics - New Zealand, transport economics, urban economics Tags: Auckland, bicycles, commuting times, compensating differentials, expressive voting, green rent seeking, Inner-city Left, New Zealand Greens, public transport, rational irrationality, search and matching, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge

I am not surprised only 7% of Auckland’s take public transport to work considering it takes much longer than any other form of commuting.

The average commute by public transport is 40 minutes as compared to less than 25 in a car. 74% of Aucklanders drive to work and another 9% are a passenger in a car.

No information was available on those who bike to work because only 1% of Aucklanders bike to work. Only 2% of all New Zealanders take a bike to work. The sample size was therefore too small. Yet another reason to ban bikes at night. Few commute on this mode of transport in Auckland.

The near identical commuting distances irrespective of the mode of transport except walking is further evidence that people are quite discerning in balancing commuting times and job selection as per the theory of compensating differentials. Indeed, average commuting times in Auckland are much the same as the average commuting time in America.

The Auckland transport data showing people commute much the same distance by any mode of transport bar walking also validates Anthony Downs’ theory of triple convergence.

Improving the commuting times in one mode of transport will mean people simply take the mode of peak hour transport that is suddenly become less congested while others who were not going to commute at peak times or start commuting at peak times as Anthony Downs explains:

If that expressway’s capacity were doubled overnight, the next day’s traffic would flow rapidly because the same number of drivers would have twice as much road space.

But soon word would spread that this particular highway was no longer congested. Drivers who had once used that road before and after the peak hour to avoid congestion would shift back into the peak period. Other drivers who had been using alternative routes would shift onto this more convenient expressway. Even some commuters who had been using the subway or trains would start driving on this road during peak periods.

Within a short time, this triple convergence onto the expanded road during peak hours would make the road as congested as it was before its expansion.

Does the minimum wage increase unemployment?

20 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, unemployment Tags: College premium, compensating differentials, education premium, evidence-based policy, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

https://twitter.com/MiltonFriedmanS/status/630956276554444800/photo/1

#Australia:highest minimum wage in OECD relative to purchasing power. Increases #youthunemployment #auspol #jobsearch http://t.co/HML9l2rD7R—

Bob Day (@senatorbobday) August 11, 2015

Over-qualification rates in jobs in the USA, UK and Canada

19 Aug 2015 2 Comments

in economics of bureaucracy, economics of education, human capital, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - USA, Public Choice Tags: British economy, Canada, compensating differentials, job shopping, offsetting behaviour, on-the-job training, search and matching, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge

In the UK, foreign-born are much more likely to be over qualified than native born highly educated not in education with less difference between men and women. More men than women are overqualified for their jobs in the UK. Over qualification is less of a problem in the UK than in the USA and Canada.

Source: OECD (2015) Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2015: Settling In.

In the USA and Canada, there are few differences between native and foreign born men in over-qualification rates. Foreign-born women tend to be more over-qualified than native born women in the USA and more so in Canada. Many more workers are overqualified for their jobs in the USA and Canada as compared to the UK.

There are large differences in the percentage of people with tertiary degrees and the education premium between these three countries that are outside the scope of this blog post. These trends may explain differences in the degree of educational mismatch.

It goes without saying that the concept of over-qualification and over-education based mismatch in the labour market is ambiguous, if not misleading and a false construct.

To begin with, under human capital theories of labour market and job matching, what appears to be over-schooling substitutes for other components of human capital, such as training, experience and innate ability. Not surprisingly, over-schooling is more prominent among younger workers because they substitute schooling for on-the-job training. A younger worker of greater ability may start in a job below his ability level because he or she expects a higher probability to be promoted because of greater natural abilities. Sicherman and Galor (1990) found that:

overeducated workers are more likely to move to a higher-level occupation than workers with the required level of schooling

Investment in education is a form of signalling. Workers invest so much education that they appear to be overqualified in the eyes of officious bureaucrats. The reason for this apparent overinvestment is signalling superior quality as a candidate. Signalling seems to be an efficient way of sorting and sifting among candidates of different ability. The fact that signalling survives in market competition suggests that alternative measure ways of measuring candidate quality that a more reliable net of costs are yet to be discovered.

A thoroughly disheartening chart if you're a graduate in the UK i100.io/mpDbJAl http://t.co/mv9izA0mbc—

i100 (@thei100) August 20, 2015

Highly educated workers, like any other worker, must search for suitable job matches. Not surprisingly, the first 5 to 10 years in the workforce are spent in half a dozen jobs as people seek out the most suitable match in terms of occupation, industry and employer. Some of these job seekers who are highly educated will take less suitable jobs while they search on-the-job for better matches. Nothing is free or instantly available in life including a good job match.

A more obvious reason for over qualification is some people like attending university and other forms of education for the sheer pleasure of it.

Anyone who encounters the words over-qualified and over-educated should immediately recall concepts such as the pretence to knowledge, the fatal conceit, and bureaucratic busybodies. As Edwin Leuven and Hessel Oosterbeek said recently:

The over-education/mismatch literature has for too long led a separate life of modern labour economics and the economics of education.

We conclude that the conceptional measurement of over-education has not been resolved, omitted variable bias and measurement error are too serious to be ignored, and that substantive economic questions have not been rigorously addressed.

Which jobs are most dangerous?

13 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in health and safety, labour economics Tags: compensating differentials, job safety

Fatal #workplace accidents most prevalent in construction & manufacturing / via @EU_Eurostat

statista.com/chart/3544/eur… http://t.co/gmG6PB5rE3—

Statista (@StatistaCharts) June 10, 2015

% of U.S. workers working from home

07 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply Tags: compensating differentials, teleworkers, time use surveys

Source: American Time Use Survey, Table 7. Employed persons working on main job at home, workplace, and time spent working at each location by class of worker, occupation, and earnings, 2014 annual averages.

The average numbers of hours working at home is about 3 hours per week and varies little by any cross-tab.

The workplace payoff of Myers Briggs personality types

03 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in human capital, labour economics, managerial economics, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: compensating differentials, economics of personality traits, occupational choice

https://twitter.com/businessinsider/status/626968055046926336/photo/1

Human Resources will assign you a personality…. #HRhumour HT @ssmoir_1973 http://t.co/Vz6vs5ODLw—

Gem Reucroft (@HR_Gem) July 30, 2015

Recent Comments