Why conspiracy theories are rational to believe

07 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture Tags: conspiracy theories

Anti-vaxxer logic

29 Oct 2016 Leave a comment

in health economics Tags: anti-vaccination movement, antiscience left, conspiracy theories, conspiracy theorists, The Great Escape, vaccinations, vaccines

Behind on my chemtrails blogging

20 Oct 2016 Leave a comment

in transport economics Tags: conspiracy theories, cranks, Quacks

Milton Friedman is said to have mesmerised several countries with a flying visit!?

30 Sep 2016 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic growth, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics, politics - Australia Tags: central banks, conspiracy theories, lags on monetary policy, monetary policy, rules versus discretion, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge

Milton Friedman visited Australia in 1975. He spoke with government officials and appeared on the TV show Monday Conference. Apparently, that was enough for him to take over Australian monetary policy setting for the foreseeable future.

When working at the next desk to the monetary policy section in the late 1980s, I heard not a word of Friedman’s Svengali influence:

- The market determined interest rates, not the reserve bank was the mantra for several years. Joan Robinson would be proud that her 1975 visit was still holding the reins.

- Monetary policy was targeting the current account. Read Edwards’ bio of Keating and his extracts from very Keynesian treasury briefings to Keating signed by David Morgan that reminded me of macro101.

See Ed Nelson’s (2005) Monetary Policy Neglect and the Great Inflation in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand who used contemporary news reports from 1970 to the early 1990s to uncover what was and was not ruling monetary policy. For example:

“As late as 1990, the governor of the Reserve Bank rejected central-bank inflation targeting as infeasible in Australia, and cited the need for other tools such as wages policy (AFR, October 18, 1990).”

Bernie Fraser was still sufficiently deprogrammed in 1993 to say that “…I am rather wary of inflation targets.” Easy to then announce one in the same speech when inflation was already 2-3%.

When as a commentator on a Treasury seminar paper in 1986, Peter Boxhall – fresh from the US and 1970s Chicago educated – suggested using monetary policy to reduce the inflation rate quickly to zero, David Morgan and Chris Higgins almost fell off their chairs. They had never heard of such radical ideas.

In their breathless protestations, neither were sufficiently in-tune with their Keynesian educations to remember the role of sticky wages or even the need for the monetary growth reductions to be gradual and, more importantly, credible as per Milton Freidman and as per Tom Sargent’s End of 4 big and two moderate inflations papers.

I was far too junior to point to this gap in their analytical memories about the role of sticky wages, and I was having far too much fun watching the intellectual cream of the Treasury senior management in full flight. At a much later meeting, another high flying deputy secretary was mystified as to why 18% mortgage rates were not reining in the current account in 1989.

Friedman’s Svengali influence did not extend to brainwashing in the monetarist creed that the lags on monetary policy were long and variable. The 1988 or 1989 budget papers put the lag on monetary policy at 1 year, which is short and rapier, if you ask me.

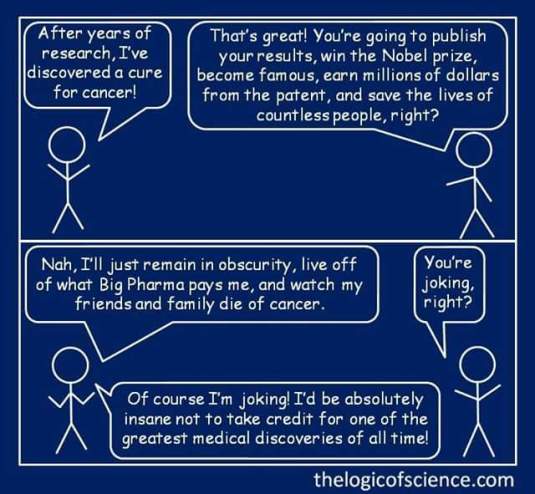

The logic of cancer cure conspiracy theories

08 Aug 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture, health economics Tags: conspiracy theories, conspiracy theorists, cranks, political psychology, Quacks

Watch Buzz Aldrin punches Bart Sibrel after being harassed on moon landing

24 Jul 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture Tags: conspiracy theories, moon landing

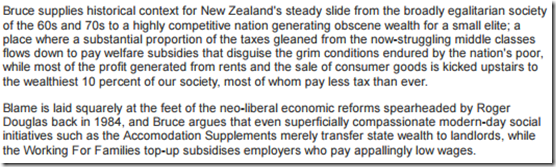

Bryan Bruce’s boy’s own memories of pre-neoliberal #NewZealand @Child_PovertyNZ

23 May 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economic history, economics of regulation, income redistribution, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: child poverty, conspiracy theories, expressive voting, family poverty, Leftover Left, living standards, neoliberalism, Old Left, pessimism bias, rational irrationality, reactionary left, top 1%

New work by Chris Ball and John Creedy shows substantial *declines* in NZ inequality.

initiativeblog.com/2015/06/24/ine… http://t.co/f94fw4Bhae—

Eric Crampton (@EricCrampton) June 24, 2015

You really are still fighting the 1990 New Zealand general election if Max Rashbrooke makes more sense than you on the good old days before the virus of neoliberalism beset New Zealand from 1984 onwards.

Source: Mind the Gap: Why most of us are poor | Stuff.co.nz.

Bryan Bruce in the caption looks upon the New Zealand of the 1960s and 70s as “broadly egalitarian”. Even Max Rashbrooke had to admit that was not so if you were Maori or female.

The present rate of technology adoption is nearly a vertical line —@blackrock https://t.co/3oS3YAI4ld—

Vala Afshar (@ValaAfshar) January 22, 2016

Maybe 65% of the population of those good old days before the virus of neoliberalism. were missing out on that broadly egalitarian society championed by Bryan Bruce.

As is typical for the embittered left, the reactionary left, gender analysis and the sociology of race is not for their memories of their good old days. New Zealand has the smallest gender wage gap of any of the industrialised countries.

The 20 years of wage stagnation that proceeded the passage of the Employment Contracts Act and the wages boom also goes down the reactionary left memory hole.

That wage stagnation in New Zealand in the 1970s and early 80s coincided with a decline in the incomes of the top 10%. When their income share started growing again, so did the wages of everybody after 20 years of stagnation. The top 10% in New Zealand managed to restore their income share of the early 1970s and indeed the 1960s. That it is hardly the rich getting richer.

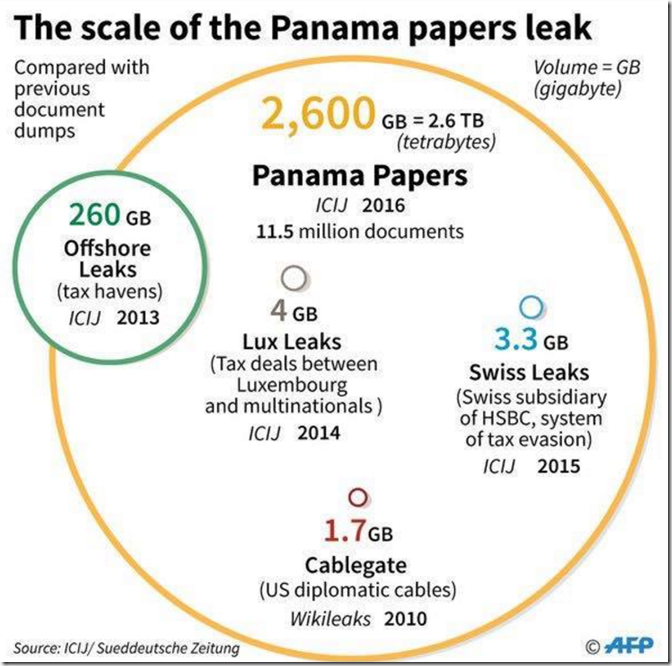

The scale of the #Panamapapers leak

16 Apr 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of crime, law and economics, property rights, public economics Tags: conspiracy theories, tax havens

@GarethMP @jamespeshaw need message discipline on @NZGreens as honest brokers

08 Apr 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, survivor principle Tags: anti-trust economics, cartel theory, competition law, conspiracy theories, economics of banking, New Zealand Greens, privatisation, state owned enterprises

Yesterday morning, Green MP Gareth Hughes posted a British Greens’ video about how other politicians are a bunch of squabbling children but the Greens are above that. It’s only the Greens who offer a “true alternative to the establishment parties” and their “same childish Punch & Judy politics”.

Later that same day Greens co-leader James Shaw posted a video that shaded the truth about the history of dividends from Kiwibank as a way of scoring points of the National Party led government.

Shaw claimed that the government is extracting more and more dividends from Kiwibank rather than letting it keep those profits as capital on which the government owned bank can be a more aggressive competitor.

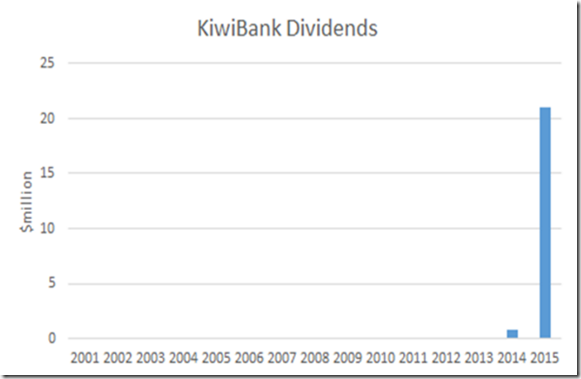

Source: Kiwibank pays its first dividend of $21 million to Government | Stuff.co.nz.

Shaw is vaguely correct in that it is dividends plural when referring to Kiwibank’s dividends. Kiwibank paid dividends of $21 million last year; and $750,000 the year before. Kiwibank has paid two dividends to New Zealand Post in its entire history since 2002.

It shades the truth to say that the government is extracting more and more dividends from Kiwibank when when it has only paid one dividend worth mentioning, which was last year.

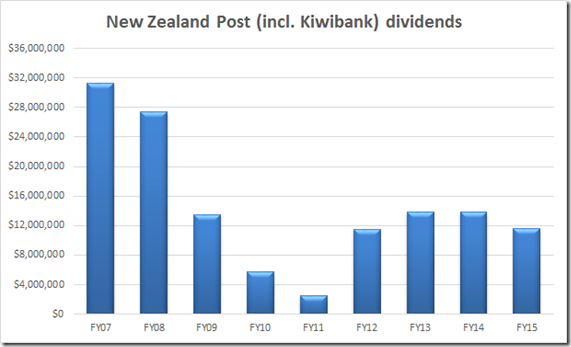

Source: New Zealand Treasury – data released under the Official Information Act.

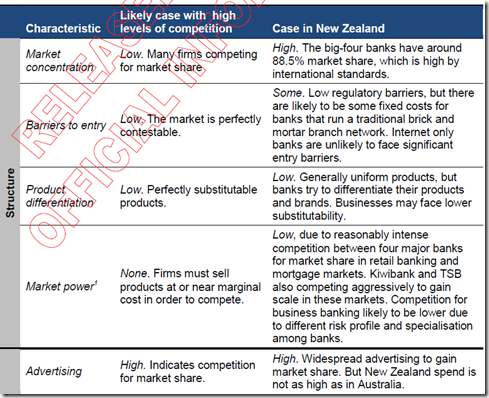

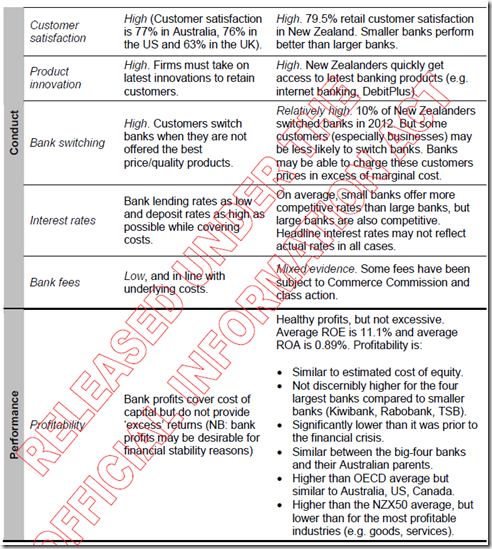

As for James Shaw’s claim that the entry of Kiwibank made banking in New Zealand much more competitive, Michael Reddell disposed of that by linking to a 2013 Treasury assessment of competition in retail banking.

Source: New Zealand Treasury Official Information Act Releases.

There are no excess profits in the New Zealand banking market for Kiwibank to undercut. Entry barriers are low, banking products are easy substitutes for each other between the competing banks, and the banks compete for market share by advertising of, for example, special packages to switch banks.

Adding to the analysis of the Treasury, Posner and Easterbrook suggest that these industry behaviours together are suspicious.

- Fixed relative market shares among top firms over time.

- Declining absolute market shares of the industry leaders.

- Persistent price discrimination.

- Certain types of exchanges of price information.

- Regional price variations.

- Identical sealed bids for tenders.

- Price, output, and capacity changes at the time of the suspected initiation of collusion.

- Industry-wide resale price maintenance or non-price vertical restraints.

- Relatively infrequent price changes; smaller price reactions as a result of known cost changes.

- Demand is highly responsive to price changes at market price.

- Level and pattern of profits relatively favourable to smaller firms.

- Particular pricing and marketing strategies.

As the Treasury noted in its analysis, there are several small banks offering competitive rates that would allow them to expand if they offered value for money over the existing offerings. Returns on equity of the big banks are not discernibly higher than for the smaller ones.

To add again to the Treasury analysis, it is not easy to organize a cartel. There are markets to divide, prices to set, and production quotas to assign. The best place to be in a cartel is outside of it undercutting the higher price and selling as much as you can before the cartel inevitably collapses. Brozen and Posner suggest the following pre-conditions to collusion:

- market concentration on the supply side;

- no fringe of small sellers;

- high transport costs from neighbouring markets;

- small variations in production costs between firms;

- readily available information on prices;

- inelastic demand at the competitive price;

- low pre-collusion industry profits;

- long lags on new entry;

- many buyers (otherwise selective discounting to big buyers will be too tempting while monitoring adherence to the agreement will be difficult);

- no significant product differentiation;

- large suppliers selling at the same level in the distribution chain;

- a simple price, credit and distribution structure;

- price competition is more important than other forms of competition;

- demand is static or declining over time; and

- stagnant technological innovation and product redesign.

Stable collusive arrangements are thus likely to be rare because the absence of any of the above conditions will tend to undermine the potential for successful collusion.

Successful cartel operation is even harder than its initial formation. Members of the cartel must continue to believe that they enjoy net profits from participating in the collusion.

The more profitable the collusive price fixing, the greater the incentive for outsiders to seek entry to compete. In cartel theory, these new entrants are known as interlopers.

The more numerous the participants in the cartel and the more lucrative the collusion, the greater the temptation for individual members to cheat and the greater the fear of each that some other member will cheat first.

Cartel members that cheat early profit the most from the cartel price before it collapses. That is why the history of cartels is a history of double-crossing. Long-term survival of the cartel has two fundamental requirements:

- cheating by a member on the cartel prices, outputs and market shares must be detectable; and

-

detected cheating must be adequately punishable without breaking-up of the cartel.

If banking was a cartel, you would not see advertising on the TV every night inducing customers to switch but you do. That advertising is cheating on the banking cartel the New Zealand Greens want to break up.

There is an infallible rule in competition law enforcement. It arises mostly crisply in merger law enforcement. If competitors oppose a merger, the merger must be pro-consumer. If the merger is anti-competitive, that merger will increase prices. The competing firms can follow those prices up and profit from the weakening of competition subsequent to the merger.

Recent Comments