Americans have more income left over after food expenses. https://t.co/PKXCfe0Maw pic.twitter.com/vKESAqEgJY

— Human Progress (@HumanProgress) January 12, 2016

Americans have more income left over after food expenses

29 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history Tags: child poverty, family poverty, food prices

More evidence from the @economicpolicy institute of the great success of the 1996 US federal welfare reforms

17 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, gender, labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, family poverty, single mothers, single parents, US welfare reforms

NZ real household incomes up 55% since 1994 but no dancing in the street by the Leftover Left

08 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, labour economics, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality Tags: child poverty, family poverty, Leftover Left, living standards, Maori economic development, Twitter left

https://twitter.com/sbancel/status/654162844884205568

Pakeha and Pasifika real household incomes increased by 55% since the low point of 1994. Maori household incomes increased by 65% since 1994.

Source: Bryan Perry, Household Incomes in New Zealand: trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2014 – Ministry of Social Development, Wellington (August 2015), Table D.6.

What is the success sequence?

08 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of education, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - USA, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, family poverty, high school dropouts, marriage and divorce, single parents, success sequence

Source: The success sequence: Conservatives think they have a formula for raising people out of poverty.

.

Adam Smith versus Jamie Whyte or is there poverty on the Starship Enterprise?

07 Jan 2016 2 Comments

in Adam Smith, applied welfare economics, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, Rawls and Nozick Tags: child poverty, family poverty, star trek

Jamie Whyte today wrote an excellent op-ed on the meaninglessness of current measures of poverty. His point was that defining poverty as 60% of the median income means the poor will always be with us. This relative definition of poverty misleads us as to the level of hardship and deprivation in society as Jamie Whyte says today:

There is no poverty in New Zealand. Misery, depravity, hopelessness, yes; but no poverty.

The poorest in New Zealand are the unemployed. They receive free medical care, free education for their children and enough cash to pay for basic food, clothing and (subsidised) housing. Most have televisions, refrigerators and ovens. Many even own cars. That isn’t poverty.

I agree that this definition of poverty in relative income terms is misleading and reflects a political agenda. When I was young, the poor were thin, now they are fat.

Poverty rates have not changed despite a greater abundance of food. Indeed, child poverty rates have increased since I was young despite this relative opulence of food.

Over the Christmas break I read Simon Chapple and Jonathan Boston’s Child Poverty in New Zealand. They included a discussion of what was poverty drawing on the relative concept of poverty of Adam Smith. Smith spoke about wrote about the differences in poverty between countries and across time:

A linen shirt … is, strictly speaking, not a necessary of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably though they had no linen.

But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt, the want of which would be supposed to denote that disgraceful degree of poverty which, it is presumed, nobody can well fall into without extreme bad conduct.

In any society, a certain level of material well-being is necessary to not be in poverty. Smith also talked about how poverty lines differ between countries starting with the discussion about shoes:

The poorest creditable person of either sex would be ashamed to appear in publick without them. In Scotland, custom has rendered them a necessary of life to the lowest order of men; but not to the same order of women, who may, without any discredit, walk about bare-footed. In France, they are necessaries neither necessaries neither to men nor to women; the lowest rank of both sexes appear there publickly, without any discredit, sometimes in wooden shoes, and sometimes bare-footed.

Under necessaries, I comprehend, not only those things which nature, but those things which the established rules of decency have rendered necessary to the lowest rank of people.

All other things I shall call luxuries; without meaning by this appellation, to throw the smallest degree of reproach upon the temperate use of them. Beer and ale, for example, in Great Britain, and wine, even in the wine countries, I call luxuries. A man of any rank may, without any reproach, abstain totally from tasting such liquors. Nature does not render them necessary for the support of life; and custom nowhere renders it indecent to live without them.

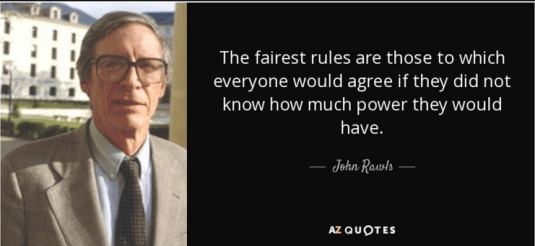

Much of the Wealth of Nations was about the natural progress of opulence under a capitalist system. There is nothing wrong with inequality as John Rawls has explained.

The fact that citizens have different talents can be used to make everyone better off. In a society governed by the difference principle, those better endowed with talents are welcome to use their gifts to make themselves better off, so long as they also contribute to the good of those less well endowed.

With his emphasis on fair distribution of income, Rawls’ initial appeal was to the Left, but left-wing thinkers started to dislike his acceptance of capitalism and tolerance of large discrepancies in income.

Will the poor always be with us? I once had an argument with a colleague at work about whether there was poverty on the Starship Enterprise.

Star Trek was supposed to be a society that had abolished money and a post-scarcity economy because everything was available through a replicator. To quote Captain Picard:

A lot has changed in three hundred years. People are no longer obsessed with the accumulation of ‘things’. We have eliminated hunger, want, the need for possessions.

The economics of the future is somewhat different. You see, money doesn’t exist in the 24th century… The acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives. We work to better ourselves and the rest of Humanity.

The Ferengi and their 285 rules of acquisition were a satire on capitalism. The Ferengi was originally meant to replace the Klingons as the Federation’s arch-rival but they were too comical.

Gene Roddenberry’s love story with socialism was a class-ridden society. In Star Trek, higher ranked officers had larger cabins, and most of all they always beamed back from the planet.

An old mate reminded me years ago that anyone who beamed down with Captain Kirk dressed in those red security officer tops were expendables. They were lucky to last 60 seconds in most episodes I watched.

Death and accommodation were class based on Star Trek but it was a supremely opulent society for everyone. That is the point to remember.

Standards are living are much better today than before for everyone despite inequalities that are quite acceptable under the difference principle of John Rawls.

Current definitions of poverty do not take into account the natural progress of opulence. In the 1970s, US Department of Energy started collecting its Household Energy Consumption Survey. This survey is one of the few accurate measures of growing affluence among the poor in America.

Not only does this survey ask about household appliances, it asked about on income. The survey is conducted every 4 years or so since the 1970s. Because of that, it is able to track the diffusion of appliances to households of varying incomes across America.

Yesterday’s luxuries at today’s necessities in poor households with a rapid diffusion of everything from air-conditioners to digital appliances. Many poor households in the USA have more space than middle-class households in Western Europe. Food is also much cheaper in the USA than in Europe.

https://twitter.com/VisualEcon/status/644080191841640448

This growing affluence of poorer Americans is despite higher measured family poverty in America according to the relative poverty measure based on the median income. That makes no sense.

@GarethMorgannz is repeating Bob Hawke’s mistake that child poverty can be solved by more money

06 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, labour economics, labour supply, politics - New Zealand, welfare reform Tags: 1996 US welfare reforms, child poverty, family poverty, universal basic income

Jess Berentson-Shaw’s series on child poverty in the Dominion Post on child poverty had two major flaws. She argues that the solution to child poverty is to give more families more money.

The first flaw is she does not discuss previous failed attempts to solve poverty with more money. For example, Bob Hawke promised in the 1987 election that no child need live in poverty by 1990. Raising the family allowance to $1 above the family poverty line did not fix child poverty. That promise was the one Hawke later said he regretted most in his public life.

During the 1987 Australian Federal election campaign, Labour Party Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced a Family Allowance Supplement that would ensure no Australian child need live in poverty by 1990. These changes in social welfare benefits and family allowance supplements would ensure that every family would be paid one per week dollar more than the poverty threshold applicable to their family situation. I know child poverty was to be done in this way because I worked in the Prime Minister’s Department at this time.

About 580,000 Australian children lived in poverty in 1987. In 2007, at least 13 per cent of children, or 730,000 people, were poor. This was after social welfare benefits and family allowance supplements were increased to $1 above the child poverty threshold.

There is an infallible test of the practicality of Left over Left dreams such as the abolition of child poverty by writing bigger and bigger cheques to those currently poor.

If you could abolish child poverty simply by increasing welfare benefits and family allowances, the centre-right parties would be all over it like flies to the proverbial as a way of camping over the middle ground and winning the votes of socially conscious swinging voters for decades to come. Many people who would naturally vote for the centre-right parties on all other issues vote for centre-left parties out of a concern for poverty and a belief that centre-left parties will give a better deal to the poor.

The notion that poverty is simply the result of a lack of money and giving people more money will abolish child poverty has never worked. As the OECD (2009, p. 171) observed:

It would be naïve to promote increasing the family income for children through the tax-transfer system as a cure-all to problems of child well-being.

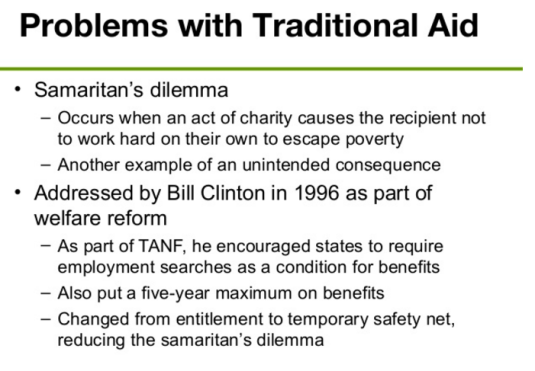

Berentson-Shaw’s second major flaw is she does not discuss the success of the 1996 US federal welfare reforms. Any serious participant in discussions of child poverty must address those 1996 US reforms.

These reforms cut Hispanic and black child poverty rates by 1/3rd in a few years by moving single mothers into employment. Time limits on welfare for single parents reduced caseloads by two thirds, 90% in some states.

After the 1996 US Federal welfare reforms, the subsequent declines in welfare participation rates and gains in employment were largest among the single mothers previously thought to be most disadvantaged: young (ages 18-29), mothers with children aged under seven, high school drop-outs, and black and Hispanic mothers. These low-skilled single mothers were thought to face the greatest barriers to employment. Blank (2002) found that:

…nobody of any political persuasion predicted or would have believed possible the magnitude of change that occurred in the behaviour of low-income single-parent families.

Employment are never married mothers increased by 50% after the US well for a reforms: employment of single mothers with less than a high school education increased by two-thirds; and employment of single mothers aged 18 to 24 approximately doubled.

Working population poverty is unchanged despite declines in elderly and child poverty #PovertyIs http://t.co/i7O7dTEUg2—

Political Line (@PoliticalLine) June 19, 2015

With the enactment of welfare reform in 1996, black child poverty fell by more than a quarter to 30% in 2001. Over a six-year period after welfare reform, 1.2 million black children were lifted out of poverty. In 2001, despite a recession, the poverty rate for black children was at the lowest point in national history.

Proposal to make child-care tax credit refundable would boost employment of working mothers bit.ly/1i1Xzcq https://t.co/2xlQQtPRJs—

The Hamilton Project (@hamiltonproj) October 29, 2015

The only modern welfare reforms to significantly cut child poverty were the US federal welfare reforms. They emphasised helping those who helped themselves, which is the classic Samaritans’ dilemma.

Countless studies show that when comparing the carrot and the stick in welfare reform, the stick is always more effective in reducing poverty and increasing employment.

The typical white family still makes $25,000 more than the typical black one: washingtonpost.com/news/wonkblog/… http://t.co/CEOADLSJdx—

Demos Action (@DemosAction) September 16, 2015

The best solution to child poverty is to move their parents into a job. Simon Chapple is clear in his book last year with Jonathan Boston:

Sustained full-time employment of sole parents and the fulltime and part-time employment of two parents, even at low wages, are sufficient to pull the majority of children above most poverty lines, given the various existing tax credits and family supports.

The best available analysis, the most credible analysis, the most independent analysis in New Zealand or anywhere else in the world that having a job and marrying the father of your child is the secret to the leaving poverty is recently by the Living Wage movement in New Zealand.

According to the calculations of the Living Wage movement, earning only $19.25 per hour with a second earner working only 20 hours affords their two children, including a teenager, Sky TV, pets, annual international travel, video games and 10-hours childcare.

This analysis of the Living Wage movement shows that finishing school so your job pays something reasonable and marrying the father of your child affords a comfortable family life. In the USA this is called the success sequence.

Single motherhood and the feminisation of poverty

31 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, child poverty, economics and fertility, engines of liberation, family poverty, marriage and divorce, marriage premium, single mothers, single parents

43.1% of single mothers are living in poverty this #MothersDay statusofwomendata.org http://t.co/OgWcmvLnDZ—

IWPR (@IWPResearch) May 10, 2015

When do rising incomes increase child poverty?

22 Aug 2015 2 Comments

in economic history, labour economics, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, family poverty, Leftover Left, measurement error, New Zealand Greens

Summary of the 222 pages of MSD's Household Incomes report: kids are still missing out BIG time. #itsnotchoice http://t.co/4x7dm1O0Wg—

Child Poverty NZ (@povertymonitor) August 13, 2015

AHC = after deducting housing costs

BHC = before deducting housing costs

‘anchored line’:

- this is the line set at a chosen level in a reference year (now 2007), and held fixed in real terms (CPI adjusted)

- the concept of ‘poverty’ here is – have the incomes of low-income households gone up or down in real terms compared with what they were previously?

‘moving line’:

- this is the fully relative line that moves when the median moves (e.g. if median rises, the poverty line rises and reported poverty rates increase even if low incomes stay the same)

- the concept of ‘poverty’ here is – have the incomes of low-income households moved closer or further away from the median?

Bryan Perry, Household Incomes in New Zealand: trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2014 – Ministry of Social Development, Wellington (August 2015), p. 133.

Source: Bryan Perry, Household Incomes in New Zealand: trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2014 – Ministry of Social Development, Wellington (August 2015), p. 133.

Is child poverty in New Zealand 245,000 children or 305,000 children?

260,000 kids in income poverty, 180,000 in material hardship, 10% in severe poverty, 3in5 in poverty for a long time http://t.co/Oy5cWftvwU—

Child Poverty NZ (@povertymonitor) May 21, 2015

If you base your estimate of child poverty on the 60% of median income after housing costs moving line, which is the number of low income households who moved further away from 60% of median income, a median which increased by 5% last year, the figure is 305,000 children after housing costs. 45,000 children are in households that is not as close to the median as last year but are not necessarily any poorer than last year in terms of money coming into the house.

45k more children in #poverty this year than last, that’s 305k Kiwi kids without life's basics. C'mon @johnkeypm! http://t.co/K8zeQpgA79—

UNICEF New Zealand (@UNICEFNZ) August 13, 2015

If you base your estimate on the anchored line, which is the number of low income households whose income has gone up on down compared to what they were on previously,the number of children in poverty has increased from 235,000 to 245,000 after housing costs. About 10,000 children are poorer than last year – poorer enough than last year to be classified as in poverty.

Poverty in America

22 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, labour economics, politics - USA, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: 1996 U.S. welfare reforms, child poverty, family poverty

Half as many blacks in the U.S. today are living in poverty as in 1960. buff.ly/1KTT5Sz http://t.co/PKK5REXr0P—

HumanProgress.org (@humanprogress) August 07, 2015

@DandLMitchell Lindsey Mitchell on poverty

15 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, family poverty, Lindsey Mitchell, welfare state

Director’s Law in New Zealand?

14 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, income redistribution, labour economics, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, Public Choice, public economics Tags: child poverty, Director's Law, family poverty, family tax credits, welfare state

One group with negative net tax liability is low- to middle-income households with dependent children. For example, single-earner families with two children can earn up to around $60,000 pa before they pay any net tax.

Around half of all households with children receive more in welfare benefits and tax credits than they pay in income tax.

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/clip_image0026_thumb.jpg?w=268&h=177)

Recent Comments