19th century Bank of England was well on to stigma effects in a banking crisis

09 Feb 2020 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, business cycles, economic history, economics of bureaucracy, economics of information, fisheries economics, industrial organisation, law and economics, macroeconomics, monetary economics, property rights, Public Choice, survivor principle Tags: adverse selection, asymmetric information, bank runs, banking crises, banking panics, lender of last resort, monetary policy, screening

John Cochrane on a big hole in the Greek bailout (and media analysis of the bailout)

15 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in currency unions, Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: bank runs, banking panics, Greece, John Cochrane, lender of last resort, sovereign bailouts, sovereign default

An average of 41% of Greek bank assets are non-performing, with loan repayments 90 days overdue or more (Barclays). http://t.co/HfXV8uapkj—

Mike Bird (@Birdyword) July 13, 2015

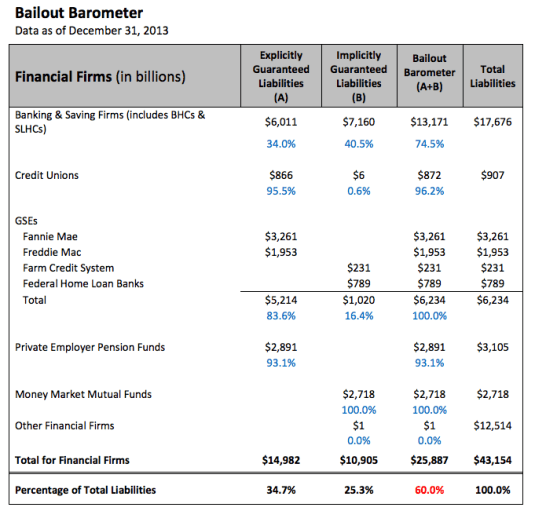

The U.S. bailout barometer.

19 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, financial economics, monetary economics, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: bailouts, deposit insurance, implicit guarantees, lender of last resort

To avert a financial panic, central banks should lend early and freely to solvent banks against good collateral but at penal rates

19 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in financial economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics, Thomas M. Humphrey Tags: lender of last resort, Thomas Humphrey, Walter Bagehot

First. That these loans should only be made at a very high rate of interest. This will operate as a heavy fine on unreasonable timidity, and will prevent the greatest number of applications by persons who do not require it. The rate should be raised early in the panic, so that the fine may be paid early; that no one may borrow out of idle precaution without paying well for it; that the Banking reserve may be protected as far as possible.

Secondly. That at this rate these advances should be made on all good banking securities, and as largely as the public ask for them. The reason is plain. The object is to stay alarm, and nothing therefore should be done to cause alarm. But the way to cause alarm is to refuse some one who has good security to offer… No advances indeed need be made by which the Bank will ultimately lose. The amount of bad business in commercial countries is an infinitesimally small fraction of the whole business…

The great majority, the majority to be protected, are the ‘sound’ people, the people who have good security to offer. If it is known that the Bank of England is freely advancing on what in ordinary times is reckoned a good security—on what is then commonly pledged and easily convertible—the alarm of the solvent merchants and bankers will be stayed. But if securities, really good and usually convertible, are refused by the Bank, the alarm will not abate, the other loans made will fail in obtaining their end, and the panic will become worse and worse.

Walter Bagehot Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market (1873).

The classical theory of the lender of last resort stressed

(1) protecting the aggregate money stock, not individual institutions,

(2) letting insolvent institutions fail,

(3) accommodating sound but temporarily illiquid institutions only,

(4) charging penalty rates,

(5) requiring good collateral, and

(6) preannouncing these conditions in advance of crises so as to remove uncertainty.

Did anyone follow these rules in the global financial crisis? The Fed violated the classical model in at least seven ways:

- Emphasis on Credit (Loans) as Opposed to Money

- Taking Junk Collateral

- Charging Subsidy Rates

- Rescuing Insolvent Firms Too Big and Interconnected to Fail

- Extension of Loan Repayment Deadlines

- No Pre-announced Commitment

- No Clear Exit Strategy

…{the Fed’s} policies are hardly benign, and that extension of central bank assistance to insolvent too-big-to-fail firms at below-market rates on junk-bond collateral may, besides the uncertainty, inefficiency, and moral hazard it generates, bring losses to the Fed and the taxpayer, all without compensating benefits. Worse still, it is a probable prelude to a severe inflation and to future crises dwarfing the current one.

Sargent, Prescott, Taylor and Kydland on the Global Financial Crisis and the Great Recession

21 Mar 2014 1 Comment

in economics of regulation, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics Tags: bank panics, Edward Prescott, Finn Kydland, global financial crisis, great recession, John Taylor, lender of last resort, moral hazard, Tom Sargent

Many of the key issues about what modern macroeconomics has to say on global financial crises are discussed in a 2010 interview with Thomas Sargent where he says that two polar models of bank crises and what government lender-of-last-resort and deposit insurance do to arrest or promote them were used to understand the GFC. They are polar models because:

-

in the Diamond-Dybvig and Bryant model of banking runs, deposit insurance and other bailouts are purely a good thing stopping panic-induced bank runs from ever starting; and

-

In the Kareken and Wallace model, deposit insurance by governments and the lender-of-last-resort function of a central bank are purely a bad thing because moral hazard encourages risk taking unless there is regulation or there is proper surveillance and accurate risk-based pricing of the deposit insurance.

In the Diamond-Dybvig and Bryant model, if there is government-supplied deposit insurance, people do not initiate bank runs because they trust their deposits to be safe. There is no cost to the government for offering the deposit insurance because there are no bank runs! A major free lunch.

Tom Sargent considers that the Bryant-Diamond-Dybvig model has been very influential, in general, and among policy makers in 2008, in particular.

Governments saw Bryant-Diamond-Dybvig bank runs everywhere. The logic of this model persuaded many governments that if they could arrest the actual or potential runs by convincing creditors that their loans were insured, that could be done at little or no eventual cost to taxpayers.

In 2008, the Australian and New Zealand governments announced emergency bank deposit insurance guarantees. In Bryant-Diamond-Dybvig style bank panics, these guarantees ward off the bank run and thus should cost nothing fiscally because the deposit insurance is not called upon. These guarantees and lender of last resort function were seen as key stabilising measures. These guarantees were called upon in NZ to the tune of $2 billion.

- The Diamond-Dybvig and Bryant model makes you sensitive to runs and optimistic about the ability of deposit insurance to cure them.

- The Kareken and Wallace model’s prediction is that if a government sets up deposit insurance and doesn’t regulate bank portfolios to prevent them from taking too much risk, the government is setting the stage for a financial crisis.

- The Kareken-Wallace model makes you very cautious about lender-of-last-resort facilities and very sensitive to the risk-taking activities of banks.

Kareken and Wallace called for much higher capital reserves for banks and more regulation to avoid future crises. This is not a new idea. Sam Peltzman in the mid-1960s found that U.S. banks in the 1930s halved their capital ratios after the introduction of federal deposit insurance. FDR was initially opposed to deposit insurance because it would encourage greater risk taking by banks.

Sargent also said that it is just wrong to say that the GFC caught modern macroeconomists by surprise: Allen and Gale’s 2007 book Understanding Financial Crises compiles many of the dynamic models of the causes of financial crises and government policies that can arrest or ignite them.

Stern and Feldman’s Too Big to Fail uses insights from the formal economic literature to warn in 2004 about the time bomb for a financial crisis set by current banking regulations and government promises.

In Great Depressions of the Twentieth Century (2007) written by a team of 24 economists, Kehoe and Prescott and others concluded that bad government policies are responsible for causing depressions. In particular, while different sorts of shocks can lead to ordinary business cycle downturns, it is overreactions by governments that can prolong and deepen the downturn, turning it into a depression. Depressions and great recessions, such as currently the case in the USA, are caused by crisis management policies that turn garden-variety recessions into something much worse. Crisis management policies distort the incentives to hire and invest and reduce competition and efficiency.

As an example, one in three unemployed in the EU are Spanish mainly because of Spanish employment protection laws.

Cahuc et al. 2012 estimated that Spanish unemployment would be 45% lower if Spain adopted the less strict French laws! About ten years ago, under French employment law, the contestants on the French version of Survivor sued successfully for wrongful dismissal by the Tribal Council! French workers cannot be laid off just to improve business profits. They can be laid off to avoid bankruptcy.

John Taylor argues that we should consider macroeconomic performance since the 1960:

- There was a move toward more discretionary policies in the 1960s and 1970s;

- A move to more rules-based policies in the 1980s and 1990s; and

- Back again toward discretion in recent years.

These policy swings are correlated with economic performance—unemployment, inflation, economic and financial stability, the frequency and depths of recessions, the length and strength of recoveries. Less predictable, more interventionist, and more fine-tuning type macroeconomic policies have caused, deepened and prolonged the current recession.

Finn Kydland considers fiscal policy to be at the heart of current problems. Instead of restructuring and investing more prudently, Western countries faced with budget shortfalls will seek to increase taxes:

- The U.S. economy isn’t recovering from the Great Recession of 2008-2009 with the anticipated strength.

- A widespread conjecture is that this weakness can be traced to perceptions of an imminent switch to a regime of higher taxes.

- The fiscal sentiment hypothesis can account for a significant fraction of the decline in investment and labor supply in the aftermath of the Great Recession, relative to their pre-recession trends.

- The perceived higher taxes must fall almost exclusively on capital income. People must suspect that the tax structure that will be implemented to address large fiscal imbalances will be far from optimal.

Those who disagree with the policy-based explanation for the depth and length of the Great Recession must explain why the US and EU economies have not recovered after the worst of the global financial crisis passed in November 2008?! The case that there were intervening government policies that prolonged and deepened each national recession is strong.

Recent Comments