.

After reading the annual reports of the Fed, Milton Friedman noticed the following pattern

16 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, great depression, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: lags on monetary policy, monetary policy

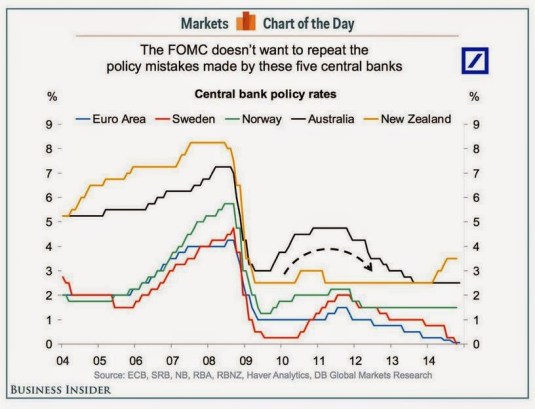

Economics New Zealand: Did we move too quickly?

09 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: monetary policy

A clickable timeline of central banking activity during the 2008 financial crisis

05 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link?

31 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, Euro crisis, great depression, great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: deflation, fiscal policy, liquidity traps, monetary policy, stabilisation policy

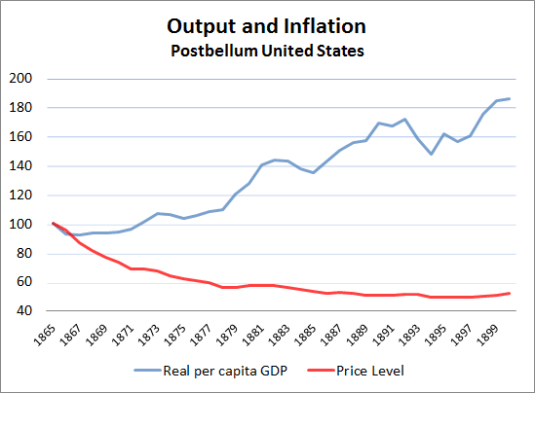

Deflation has a bad reputation. People blame deflation for causing the great depression in the 1930s. What worse reputation can you get as a self-respecting macroeconomic phenomena?

The inconvenient truth for this urban legend is empirical evidence of deflation leading to a depression is rather weak.

The most obvious is confounding evidence, is up until the great depression, deflation was commonplace. In the late 19th century, deflation coincided with strong growth, growth so strong that it was called the Industrial Revolution.

For deflation to be a depressing force, something must have happened in the lead up to the Great Depression to change the impact of deflation on economic growth.

Atkeson and Kehoe in the AER looked into the relationship between deflation and depressions and came up empty-handed.

Deflation and depression do seem to have been linked during the 1930s. But in the rest of the data for 17 countries and more than 100 years, there is virtually no evidence of such a link.

Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link?

Andrew Atkeson, and Patrick J. Kehoe, 2004.

Are deflation and depression empirically linked? No, concludes a broad historical study of inflation and real output growth rates. Deflation and depression do seem to have been linked during the 1930s. But in the rest of the data for 17 countries and more than 100 years, there is virtually no evidence of such a link.

View original post 1,842 more words

The success of monetarism and the death of the correlation between monetary growth and inflation

30 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, econometerics, economics of bureaucracy, economics of information, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: lags on monetary policy, Levis Kochin, monetary policy

Monetarists blame fluctuations in inflation on excessively volatile growth in monetary aggregates. In 1982, Friedman defined monetarism in an essay on defining monetarism as follows:

Like many other monetarists, I have concluded that the most important thing is to keep monetary policy from doing harm.

We believe that a steady rate of monetary growth would promote economic stability and that a moderate rate of monetary growth would prevent inflation

The U.S. data supported this hypothesis about the volatility of monetary growth and inflationuntil 1982, but since 1983 monetary aggregates have been essentially uncorrelated with subsequent inflation in the U.S.

Levis Kochin pointed out in 1979 that a well designed monetary policy would lead to zero correlation between any measure of monetary policy and subsequent inflation. The reason for this is the correlation between any variable and a constant is zero.

If monetary growth is stable, say, a constant growth rate of 4% per year, as advocated by Milton Friedman, monetary growth will have no correlations with any variable:

Poole (1993, 1994) and Tanner (1993) also argue that one predictable consequence of optimal monetary policy is that the correlation between monetary policy instruments and policy goals will be driven to zero.

Poole further contends that it is obvious to any careful reader of Theil (1964) that optimally variable policy will give rise to a zero correlation between policy and goal variable…

In 1966 Alan Walters, a U.K. monetarist, observed:

If the [monetary] authority was perfectly successful then we should observe variations in the rate of change of the stock of money but not variations in the rate of change of income… [a]ssuming that the authority’s objective is to stabilize the growth of income.

Milton Friedman in 2003, wrote about how the Fed acquired a good thermostat:

The contrast between the periods before and after the middle of the 1980s is remarkable.

Before, it is like a chart of the temperature in a room without a thermostat in a location with very variable climate; after, it is like the temperature in the same room but with a reasonably good though not perfect thermostat, and one that is set to a gradually declining temperature.

Sometime around 1985, the Fed appears to have acquired the thermostat that it had been seeking the whole of its life…

Prior to the 1980s, the Fed got into trouble because it generated wide fluctuations in monetary growth per unit of output. Far from promoting price stability, it was itself a major source of instability as Chart 1 illustrates.

Yet since the mid ’80s, it has managed to control the money supply in such a way as to offset changes not only in output but also in velocity.

Nick Rowe explained the difficulty of causation and correlation under different policy regimes and Milton Friedman’s thermostat superbly as an econometric problem Nick Rowe:

If a house has a good thermostat, we should observe a strong negative correlation between the amount of oil burned in the furnace (M), and the outside temperature (V).

But we should observe no correlation between the amount of oil burned in the furnace (M) and the inside temperature (P). And we should observe no correlation between the outside temperature (V) and the inside temperature (P).

An econometrician, observing the data, concludes that the amount of oil burned had no effect on the inside temperature. Neither did the outside temperature. The only effect of burning oil seemed to be that it reduced the outside temperature. An increase in M will cause a decline in V, and have no effect on P.

A second econometrician, observing the same data, concludes that causality runs in the opposite direction. The only effect of an increase in outside temperature is to reduce the amount of oil burned. An increase in V will cause a decline in M, and have no effect on P.

But both agree that M and V are irrelevant for P. They switch off the furnace, and stop wasting their money on oil.

Subsequent work of Levis Kochin showed that if the effects of fluctuations in monetary aggregates were not precisely known then the optimal policy would produce negative correlations between monetary aggregates and inflation:

The negative correlation results from coefficient uncertainty because the less certain we are about the size of a multiplier, the more cautious we should be in the application of the associated policy instrument.

Therefore, although optimal policy leads to lack of correlation between the goal and control variables if the coefficient is known, it will lead to a negative relationship if there is coefficient uncertainty. The higher the uncertainty, the more cautious will be the optimal policy response. Also, if the control variable can’t be controlled perfectly then the correlation between the goal and the control variable becomes positive i.e., the control errors are random…

Uncertainty about the impact of a policy will stay the hand of any bureaucrat , much less a central banker, as Kochin and his co-author explain:

Uncertainty should lead to less policy action by the policymakers. The less policymakers are informed about the relevant parameters, the less activist the policy should be. With poor information about the effects of policy, very active policy runs a higher danger of introducing unnecessary fluctuations in the economy.

What influence did Milton Friedman have on 1980s and 1990s Australian monetary policy?

29 Jan 2015 3 Comments

in F.A. Hayek, Milton Friedman, monetarism, politics - Australia Tags: conspiracy theorists, conspiratorial left, inflation targeting, monetary policy, vast right-wing conspiracy

The Hayek and Friedman Monday conferences on the ABC in 1976 and 1975 are still ruling the Australian policy roost, if some of the Left over Left in Australia are to be believed. Milton Friedman is said to have mesmerised several countries with a flying visit with his Svengali powers of persuasion.

When working at the next desk to a monetary policy section in the Australian Prime Minister’s Department in the late 1980s, I heard not a word of Friedman’s Svengali influence:

• The market determined interest rates, not the Reserve Bank was the mantra for several years. Joan Robinson would have been proud that her 1975 Monday conference was still holding the reins.

• Monetary policy was targeting the current account. Read Edwards’ biography of Keating and his extracts from very Keynesian Treasury briefings to Keating signed by David Morgan that reminded me of Keynesian macro101.

When as a commentator on a Treasury seminar paper in 1986, Peter Boxhall – fresh from the US and 1970s Chicago educated – suggested using monetary policy to reduce the inflation rate quickly to zero, David Morgan and Chris Higgins almost fell off their chairs. They had never heard of such radical ideas.

In their breathless protestations, neither were sufficiently in-tune with their Keynesian educations to remember the role of sticky wages or even the need for the monetary growth reductions to be gradual and, more importantly, credible as per Milton Freidman and as per Tom Sargent’s end of 4 big and two moderate inflations papers in the early 1980s.

I was far too junior to point to this gap in their analytical memories about the role of sticky wages, and I was having far too much fun watching the intellectual cream of Treasury senior management in full flight. (I read Friedman & Sargent much later).

The competing visions of stabilisation policy have been defined by Franco Modigliani and Milton Friedman

26 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economics of information, history of economic thought, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: Franco Modigliani, Keynes in macroeconomics, monetary policy, stabilisation policy, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Recent Comments