Saving Endangered Species

25 Sep 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, Austrian economics, comparative institutional analysis Tags: endangered species, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

Seinfeld Economics: The Shower Head (black markets)

07 Sep 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economics, economics of media and culture, environmental economics, environmentalism, television Tags: black markets, nanny state, offsetting behaviour, Seinfeld, The fatal conceit, water economics

The iron law of prohibition

03 Jul 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, health economics Tags: alcohol regulation, black markets, economics of prohibition, economics of smoking, marijuana decriminalisation, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretense the knowledge

Does @nztreasury @moturesearch understand its own 90-day trials research?

17 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, econometerics, economics of regulation, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand Tags: employment law, employment protection law, employment regulation, offsetting behaviour, probationary periods, trial periods

https://twitter.com/moturesearch/status/743595301345333248

Media reporting and Motu’s own tweet on its research contradict its own conclusions about what it found about the introduction of 90-day trial periods for new jobs in New Zealand.

https://twitter.com/moturesearch/status/743563189451841537

Motu’s executive summary is both as bold as the Motu tweet and directly contradicts it

We find no evidence that the ability to use trial periods significantly increases firms’ overall hiring; we estimate the policy effect to be a statistically and economically insignificant 0.8 percent increase in hiring on average across all industries.

However, within the construction and wholesale trade industries, which report high use of trial periods, we estimate a weakly significant 10.3 percent increase in hiring as a result of the policy.

No evidence means no evidence. Not no evidence but we did find some evidence in two large industries – evidence of a 10.3% increase in hiring. That is a large effect.

Both economic and statistical significance matter. Not only is the effect of 90-day trial periods in the construction and wholesale trades other than zero, 10% is large – a hiring boom. No evidence of any effects on employment of 90 day trial periods means no evidence.

Neither Treasury nor Motu understand their own research and the evidence of large effects in two industries. Can you conclude you have no evidence when you have some evidence, which they did in construction and wholesale trades? There is evidence, there is not no evidence.

The paper was weak in hypothesis development and in its literature review. It was not clear whether the paper was testing the political hypothesis or the economic hypotheses. Neither were well explained or situated within modern labour economics or labour macroeconomics. If a political hypothesis does not stand up as a question of applied price theory, you cannot test it.

The Motu paper does not remind that graduate textbooks in labour economics show that a wide range of studies have found the predicted negative effects of employment law protections on employment and wages and on investment and the establishment and growth of businesses:

1. Employment law protections make it more costly to both hire and fire workers.

2. The rigour of employment law has no great effect on the rate of unemployment. That being the case, stronger employment laws do not affect unemployment by much.

3. What is very clear is that is more rigourous employment law protections increase the duration of unemployment spells. With fewer people being hired, it takes longer to find a new job.

4. Stronger employment law protections also reduce the number of young people and older workers working age who hold a job.

5. The people who suffer the most from strong employment laws are young people, women and older adults. They are outside looking in on a privileged subsection of insiders in the workforce who have stable, long-term jobs and who change jobs infrequently.

Trial periods are common in OECD countries. There is plenty of evidence that increased job security leads to less employee effort and more absenteeism. Some examples are:

- Sick leave spiking straight after probation periods ended;

- Teacher absenteeism increasing after getting tenure after 5-years; and

- Academic productivity declining after winning tenure.

Jacob (2013) found that the ability to dismiss teachers on probation – those with less than five years’ experience – reduced teacher absences by 10% and reduced frequent absences by 25%.

Studies also show that where workers are recruited on a trial, employers have to pay higher wages. For example, teachers that are employed with less job security, or with longer trial periods are paid more than teachers that quickly secure tenure.

Workers who start on a trial tend to be more productive and quit less often. The reason is that there was a better job match. Workers do not apply for jobs to which they think they will be less suited. By applying for jobs that the worker thinks they will be a better fit, everyone gains in terms of wages, job security and productivity. For more information see

- Pierre Cahuc and André Zylberberg, The Natural Survival of Work, MIT Press, 2009;

- Tito Boeri and Jan van Ours, The Economics of Imperfect Labor Markets, MIT Press, 2nd edition (2013);

- Dale T. Mortensen, “Markets with Search Friction and the DMP Model”, American Economic Review 101, no. 4 (June 2011): 1073-91;

- Christopher Pissarides. “Equilibrium in the Labor Market with Search Frictions”, American Economic Review 101 (June 2011) 1092-1105;

- Christopher Pissarides, “Employment Protection”, Labour Economics 8 (2001) 131-159.

- Eric Brunner and Jennifer Imazeki, “Probation Length and Teachers Salaries: Does Waiting Payoff?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 64, no. 1 (October 2010): 164-179.

- Andrea Ichino and Regina T. Riphahn, “The Effect of Employment Protection on Worker Effort – A Comparison of Absenteeism During and After Probation”, Journal of the European Economic Association 3 no. 1 (March 2005), 120-143;

- Christian Pfeifer “Work Effort During and After Employment Probation: Evidence from German Personnel Data”, Journal of Economics and Statistics (February 2010); and

- Olsson, Martin “Employment protection and sickness absence”, Labour Economics 16 (April 2009): 208-214.

In the labour market, screening and signalling take the form of probationary periods, promotion ladders, promotion tournaments, incentive pay and the back loading of pay in the form of pension vesting and other prizes and bonds for good performance over a long period.

There is good reasons to have strong priors about how employment regulation will work. Employment law protects a limited segment of the workforce against the risk of losing their job. These are those who have a job and in particular those that have a steady job, a long-term job.

The impact of the introduction of trial periods on employment will be ambiguous because the lack of a trial period can be undone by wage bargaining.

- If you have to hire a worker with full legal protections against dismissal, you pay them less because the employer is taking on more of the risk if the job match goes wrong. If they work out, you promote them and pay them more.

- If you hire a worker on a trial period, they may seek a higher wage to compensate for taking on more of the risks if the job match goes wrong and there is no requirement to work it out rather than just sack them.

The twist in the tail is whether there is a binding minimum wage. If there is a binding minimum wage, either the legal minimum or in a collective bargaining agreement, the employer cannot reduce the wage offer to offset the hiring risk so fewer are hired.

The introduction of trial periods will affect both wages and employment and employment more in industries that are low pay or often pay the minimum wage. Motu found large effects on hiring in two industries that used trial periods frequently. That vindicates the supporters of the law.

Motu said that 36% of employers have used trial periods at least once. The average is 36% of employers have used them with up to 50% using them in construction and wholesale trade. That the practice survives in competition for recruits suggested that it has some efficiency value.

The large size of the employment effect in construction and wholesale trades is indeed a little bit surprising. Given that a well-grounded in economic theory hypothesis about the effect of trial period is ambiguous in regard to what will happen to wages and unemployment, a large employment effect is a surprise. If Motu had spent more time explaining employment protection laws and what hypotheses they imply, that surprise would have come to light sooner.

Motu’s research for the remaining New Zealand industries was a bit of an outlier. It should have spent more time explaining how to manage that anomalous status in light of the strong priors impartial spectators are entitled to have on the economics of employment protection laws.

A conflicting study about the effects of any regulation should be no surprise. If there are not conflicting empirical studies, the academics are not working hard enough to win tenure and promotion. Extraordinary claims nonetheless require extraordinary evidence.

Dr Mark Pennington – ‘Robust Political Economy’

20 May 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economics of media and culture, economics of regulation, entrepreneurship, environmental economics, industrial organisation, liberalism Tags: offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Will @JulieAnneGenter’s KiwiBank plan bankrupt KiwiPost? @JordNZ

03 Apr 2016 Leave a comment

in financial economics, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, privatisation, survivor principle Tags: economics of banking, government ownership, KiwiBank, New Zealand Greens, offsetting behaviour, rational irrationality, state owned enterprises, The fatal conceit

The Greens are followed up on an earlier suggestion by Julie Anne Genter, the Green’s Shadow Minister of Finance, that KiwiBank should be refocused to keeping interest rates low. To that end, it would not be required to pay dividends to the government to help fund the effort. KiwiBank has only just started paying dividends to its parent, KiwiPost.

If that were to be the case, that KiwiBank was no longer be required to pay dividends, that would blow quite a hole in the balance sheet of its parent company KiwiPost.

KiwiPost owns the share capital of KiwiBank, which must be valued on a commercial basis to pass auditing as a state owned enterprise which is commercially orientated.

Source: Historic $21 million dividend paid by state owned bank Kiwibank | interest.co.nz.

That share capital owned by KiwiPost in KiwiBank would be have to be written off if KiwiBank were to pay no further dividends because it is no longer commercially orientated entity. Such a write-off of its investment in KiwiBank would write off most of Kiwi Post’s equity capital.

The reason why state owned enterprises are required to be valued on commercial principles is to ensure that any subsidies or other favours sought by politicians show up in the profit and loss statement or the balance sheet through asset write-offs. Section 7 of the State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986 non-commercial activities states that:

Where the Crown wishes a State enterprise to provide goods or services to any persons, the Crown and the State enterprise shall enter into an agreement under which the State enterprise will provide the goods or services in return for the payment by the Crown of the whole or part of the price thereof.

This statutory safeguard ensures that the cost of any policies proposed by ministers, and the Greens are very keen on transparency and independent costing of political promises, are plain to all.

@NZGreens expand KiwiBank into wrong market to cut mortgage rates @JulieAnneGenter

03 Apr 2016 1 Comment

in industrial organisation, monetary economics, politics - New Zealand, survivor principle Tags: economics of banking, government ownership, KiwiBank, New Zealand Greens, offsetting behaviour, privatisation, rational irrationality, state owned enterprises, The fatal conceit

The Greens want to cut mortgage rates by having KiwiBank expand in business lending. Wrong market.

This expansion into a market that is not the mortgage market is to be underwritten by a capital injection as the Greens explain:

- Inject a further $100 million of capital in KiwiBank to speed its expansion into commercial banking;

- Allow KiwiBank to keep more of its profits to help it grow faster; and,

- Give KiwiBank a clear public purpose to lead the market in passing on interest rate cuts.

Note well that the $100 million capital injection is to expand in to commercial banking. More aggressive passing on of interest rate cuts may jeopardise credit ratings if this lowers the profitability of KiwiBank. KiwiBank has an A- rating

The bigger hole in the policy is the more aggressive mortgage rate setting by KiwiBank will be done by keeping more of its profits and paying fewer dividends to its parent company Kiwi Post and through that to the taxpayer. There are next to no dividends currently to stop distributing to fund a more aggressive mortgage rate setting policy.

Source: KiwiBank pays its first dividend of $21 million to Government | Stuff.co.nz.

KiwiBank paid its first dividend last year. Prior to that, the bank kept all profits to allow it to expand its lending base. $20 million in foregone dividends does not go far given the actual size of all lending markets in New Zealand.

Source: G1 Summary information for locally incorporated banks – Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

KiwiBank is minnow in the mortgage market and a pimple in commercial lending. Rapid business expansion is risky in any market, much less in banking.

The government has declined further capital injections so profits were retained to meet capital adequacy ratios. The government in 2010 earmarked NZ$300 million for an uncalled capital facility for NZ Post to help maintain its credit rating and KiwiBank’s growth.

Saving the best for last, KiwiBank last year announced plans to borrow up to $150 million through an issue of BB- perpetual capital notes to be used to bolster the bank’s regulatory capital position.

The Margin for the Perpetual Capital Notes has been set at 3.65% per annum and the interest rate will be 7.25% per annum for the first five years until the first reset date of 27 May 2020. Kiwi Capital Funding Limited is not guaranteed by KiwiBank, New Zealand Post nor the New Zealand Government.

The Perpetual Capital Notes have a BB- credit rating compared to KiwiBank which has an A- rating. These capital notes were issued in addition to prior subordinate debt in the form of CHF175 million (about NZ$233 million) worth of 5-year bonds.

I doubt that KiwiBank can raise capital through subordinated debt under normal commercial conditions if it does not plan to seek profits in the same way as other commercial banks do. The current issue of Perpetual Capital Notes are already rated as junk bonds:

An issue of $150 million of perpetual capital notes from KiwiBank with a speculative, or "junk", credit rating have been priced at the bottom of their indicative margin range.

The closest the prospectus for these Perpetual Capital Notes got to complementing KiwiBank changing from a normal business to being a public good is the following risk statement:

Kiwibank’s banking activities are subject to extensive regulation, mainly relating to capital, liquidity levels, solvency and provisioning.

Its business and earnings are also affected by the fiscal or other policies that are adopted by various regulatory authorities of the New Zealand Government.

The interest rate on this subordinate debt will go up to offset the additional risk of aggressive lending and aggressive expansion, which will cancel out many of the advantages of not having to pay for dividends and the capital injection.

That discipline is one of the purposes of subordinate debt in the regulatory capital of banks. This is to provide another pair of eyes and ears to watch the performance of the bank and through rising costs of lending and risk ratings, signal trouble of imprudent lending and lack of cost control.

The proposal to use KiwiBank to lower mortgage rates does not add up. KiwiBank does not pay much in the way of dividends to fund such a foray. KiwiBank is already far more leveraged than any other New Zealand major bank.

@AmyAdamsMP 3 strikes deters many crimes but with a twist @dbseymour @greencatherine

17 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of crime, law and economics Tags: career criminals, criminal deterrence, habitual criminals, Leftover Left, marginal deterrence, offsetting behaviour, primate punishment, unintended consequences

A card-carrying Leftist would not know what to do with this study by Radha Iyengar. In their life mission of excusing criminals, they could bait and switch. Quickly acknowledged the results of the study, a massive reduction in serious crime, then go on as fast as possible to the unintended consequences on marginal deterrence. 3rd strike offenders tend to commit more violent crimes because they have less to lose. That is basic applied price theory.

Source: Do three-strikes laws make criminals more violent?

Sadly, card-carrying leftists denied themselves this argument when arguing against 3 strikes when the laws before Parliament. You have to admit the deterrence works in order to argue that 3 strikes and you are out screws up marginal deterrence.

To be fair, the Left did not do that fully. The standard argument against life without parole is that these prisoners will have nothing to lose and will be difficult for the prison guards to manage. That is, life without parole screws up marginal deterrence even among hardened criminals.

The impact of changes in behaviour on life expectancy since 1960

25 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, health economics Tags: economics of obesity, economics of smoking, life expectancies, offsetting behaviour, The Great Escape

Greater maternity leave will increase the gender wage gap

31 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, poverty and inequality Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, gender wage gap, high-powered jobs, offsetting behaviour, Parental leave, paternity leave, unintended consequences

@Greenpeace leave it in the ground campaign increases emissions @RusselNorman

06 Dec 2015 1 Comment

in economics of regulation, energy economics, environmental economics, global warming Tags: Hotelling, offsetting behaviour, Oil prices, OPEC, The fatal conceit

Matthew Kahn wrote a fascinating blog post today on the impact of climate change, regulatory risks and fossil fuels disinvestment campaigns on investment portfolios.

At the end of that post, Kahn discussed the implications of a threatened carbon tax extraction rates of fossil fuels and the level of greenhouse gases:

Suppose that Exxon is aware that there will be a rising $100 carbon tax 50 years from now. Al Gore has claimed (in a 2014 WSJ piece) that this carbon pricing will lead to “stranded assets” and Exxon shareholders will suffer greatly.

He needs to study his Hotelling no-arbitrage condition. Exxon will simply increase its extraction upfront to avoid this tax and the carbon emissions will occur earlier!

Regulatory uncertainty fostered by Greenpeace will have the same result of increasing extraction rates and carbon emissions with it because of the lower oil prices.

If Greenpeace looks like implementing any of its anti-growth, anti-poor, antidevelopment policies in a country, investors will respond by extracting as much as they can in anticipation of the regulatory crackdown.

Not long after I joined the Department of Finance from university, I remember attending a Treasury seminar that gave a property rights explanation of oil prices in the 1970s.

It was an alternative hypothesis to the OPEC cartel explanation. This was always a clumsy explanation because of the instability of cartels. Not only does OPEC not control the majority of production even in the 1970s, several members have been at war with each other and other OPEC member countries frequently in terrible financial straits with every incentive to cheat on their OPEC production quotas

Under the property rights hypothesis for oil prices, the oil companies anticipated nationalisation and pumped as much oil as they could before they were nationalised. This depressed prices prior to these nationalisations for as far back as the mid-50s. After these nationalisations, the oil companies became contractors who ran the oil fields on behalf of the national government who expropriated them.

After the nationalisation in the late 60s and early 70s, the radical change in property rights structure reduced extraction rates and with it increased oil prices in the international markets.

The oil price increases were a result of the change in control over production from the oil companies to the oil-producing countries. With these nationalisations there was a change from high rates of time preference to low rates on the part of the production decision-makers.

There was over-depletion because of insecure property rights. OPEC deserves credit for introducing long-overdue conservation policies to the benefit of generations of consumers then unborn.

The same logic applies to threats of a carbon tax. That risk encourages more depletion today so oil producers can sell at the untaxed rate. This will increase greenhouse gas emissions because oil prices will be depressed.

Policies that limit or reduce revenues in the future will induce the resource owners to bring their sales forward to the present. To quote Hans-Werner Sinn:

In my view, the Green Paradox is not simply a theoretical possibility. I believe it explains why fossil fuel prices have failed to rise since the 1980s, despite decreasing stocks of fossil fuels and the vigorous growth of the world economy.

The emergence of green policy movements around the world, rising public awareness of the climate problem, and increased calls for demand reducing policy measures, ranging from taxes and demand constraints to subsidies on green technologies, have alarmed resource owners.

In fact, while most of us perceived these developments as a breakthrough in the battle against global warming, resource owners viewed them as efforts that threatened to destroy their markets. Thus, in anticipation of the implementation of these policies, they accelerated their extraction of fossil fuels, bringing about decades of low energy prices.

Peak China

20 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, population economics Tags: China, offsetting behaviour, one child policy, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

Is the living wage a form of indirect sex discrimination?

03 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, gender, labour economics, Marxist economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand Tags: expressive voting, living wage, offsetting behaviour, rational irrationality, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

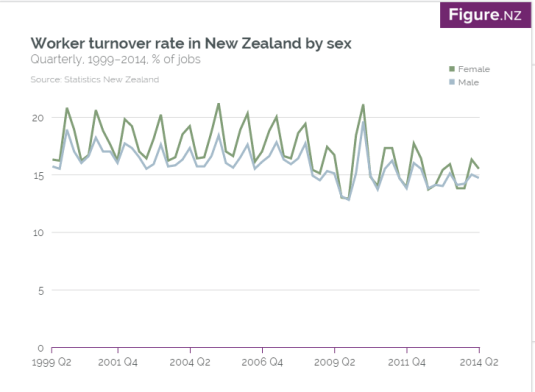

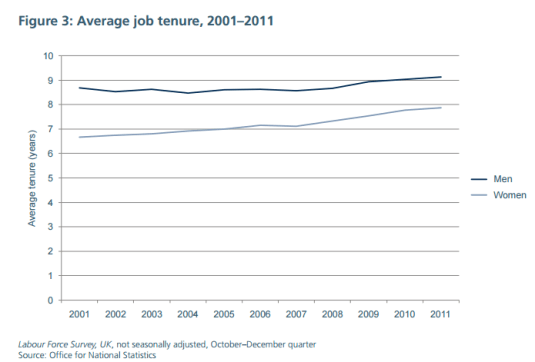

The living wage will certainly be to the profit of incumbent workers at the time of the wage increase but that is provided that their employer stays in business. The introduction of a living wage will result in indirect sex discrimination because of the higher job turnover rates of women. Women also have shorter average job tenures than men in any particular job.

Source: Worker turnover rate in New Zealand by sex – Figure.NZ.

Any benefit premised on not quitting jobs discriminates against women because of their higher job quit rates. More women than men will have to quit living wage jobs because of motherhood and other changes in their personal circumstances. Isn’t that discrimination?

One in six workers change their jobs every year. That job turnover rate is higher among the workers with less human capital simply because both sides of the job match have less reasons to continue. A job quit or job layoff for a less skilled worker does not result as much of a loss of job specific and firm specific human capital than would be the case if the worker was more skilled with more firm-specific human capital.

One of the iconic empirical facts of the labour market is job turnover rates are higher and job layoff rates are higher for less skilled workers. As workers acquire more job specific human capital, they are more reluctant to quit and their employer hesitate before laying them off. This is because of the firm specific human capital which both invested would have to be written off.

Women quit jobs more often than men, work part-time or switch between part-time and full-time work more often than men and enter and re-enter to the workforce because of motherhood and maternity leave. Women also tend to invest in more generalised, more mobile human capital. Women anticipate a more intermittent labour force participation and more spells of part-time work. As such, women have less reasons to invest in specific human capital if they anticipate leaving because of motherhood and either changing jobs more often are working part-time. If you are changing jobs more often, such as women do, investing in more general human capital and less in specific capital increases options when searching for vacancies.

Any benefit of the living wage will erode faster for women because they quit jobs at a higher rate than men. Is this indirect sex discrimination? This higher job turnover rate is driven by human capital investment strategies and career plans. The living wage, which privileges the incumbent workers at the time the living wage increases implemented, discriminates against female workers because they change jobs more often or are likely to quit sooner after the living wage was initially implemented.

The particular form of indirect sex discrimination at hand arises from the Golden Handcuffs effect of the living wage. Closer Together Whakatata Mai – reducing inequalities explain the Golden Handcuffs effect this way:

You may have noticed in the article it is actually the SAME people being paid the living wage (“all of them have stayed on as staff”). This is how labour markets can work if employers make different choices. If you look at the Living Wage employers – they haven’t hired a whole new set of people – they have invested in the people they already have. The world has not ended and many more people are happy and businesses and organisations are doing just fine.

Even the proponents of the living wage admit that a living wage increase will segment the labour market and create insiders and outsiders with the insiders paid more than what used to be called the reserve army in the unemployed by the same crowd of activists. A reduction in job turnover will increase unemployment durations because there are fewer vacancies posted every period.

Hopefully all the existing employees of the living wage employer are capable of the requisite up skilling they need to match their new productivity targets. Not everyone did well at school. One of the reasons workers on low wages are on those low wages because they perhaps didn’t do as well at school as activists who appointed themselves to speak for them. A harsh reality of life is 50% of the population have below-average IQs.

This up skilling answer to the cost to employers of a living wage increase is a variation of the standard policy response in a labour market crisis. That standard labour market policy response in crisis is send them on a course. Sending them on a course as a response to a crisis makes you look like you care and by the time they graduate the problem will probably have fixed itself. Most problems do. I found this bureaucratic response to labour market crises to repeat itself over and over again while working in the bureaucracy.

The reason was sending them on a course was so popular with geeks as yourself sitting at your desk as a policy analysis, minister or political activist all did well at university. You assume others will do well through further education and training including those who have neither the ability or aptitude to succeed in education. People don’t go on from high school to higher education for a range of reasons that include a lack of motivation to study or a simple lack of ability no matter how hard they try.

The living wage hypothesis about reduced turnover, up-skilling and greater motivation is a small example of the American company that decided to pay a minimum wage of $70,000 a year. Those workers who cannot earn as much of this elsewhere would never quit. Some of his better employers quit because they resented being paid the same as less productive employees. Hopefully, the minority shareholder suing his brother who is the CEO for offering that above market wage doesn’t end up bankrupting the company. As such, the incumbent workers’ fortunes are unusually closely tied to their existing employer if they are paying above the going rate in their industry and occupation.

I suppose you could hold on like grim death but women tend to have more reasons to move on than men if only because of pregnancy and motherhood. These golden handcuffs are of less value to them than to men. Younger workers are also less advantaged because many young New Zealanders take a overseas working holiday of several years, if not more. If they have a living wage job now that have to give up that advantage.

Workers who lack the labour productivity to earn a wage equivalent of the living wage elsewhere will never quit a living wage job, and will have a much reduced incentive to up-skill or seek promotion. There will be less internal reward for undertaking additional training or job responsibilities among low skilled is because the living wage will mean they will not get a wage rise. That wage rise is gobbled up by the living wage increase if you’re already a low-paid worker.

Naturally, as vacancies arise, recruits will be drawn from a much higher quality recruitment attracted by the higher wage at the living wage employer. The less skilled workers who don’t currently work for the living wage employer will miss out completely.

Did the New Zealand film industry just eat our lunch? By Jason Potts

01 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of media and culture, fiscal policy, industrial organisation, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, rentseeking, survivor principle Tags: film subsidies, Hollywood economics, industry policy, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge, unintended consequences

James Cameron is going to film the next three instalments of the Avatar franchise in New Zealand. He promises to spend at least NZ$500 million, employ thousands of Kiwis, host at least one red-carpet event, include a NZ promotional featurette in the Avatar DVDs, and will personally serve on a bunch of Film NZ committees, and probably even bring scones, all in return for a 25% rebate on any spending he and his team do in the country (up from a 20% baseline to international film-makers) that is being offered by the New Zealand Government.

The implication that many media reports are running with is that this is a loss to the Australian film industry, that we should be fighting angry, and that we should hit back at this brilliantly cunning move by the Kiwi’s by increasing our film industry rebates, which currently are about 16.5% (these include the producer and location offsets, and the post, digital and visual effects offset) to at very least 30%. These rebates cost tax-payers A$204 million in 2012, which hardly even buys you a car industry these days.

So what are the economics of this sort of industry assistance? Is this something we should be doing a whole lot more of? Was the NZ move to up the rebate especially brilliant? First, note that James Cameron has substantial property interests in New Zealand already, so this probably wasn’t as up for grabs as we might think. But if that’s how the New Zealand taxpayers want to spend their money, that’s up to them. The issue is should we follow suit?

The basic economics of this sort of give-away is the concept of a multiplier “”), which is the theory that an initial amount of exogenous spending becomes someone else’s income, which then gets spent again, creating more income, and so on, creating jobs and exports and all sorts of “economic benefits” along the way.

People who believe in the efficacy of Keynesian fiscal stimulus also believe in the existence of (>1) multipliers. Consultancy-based “economic impact” reports do their magic by assuming greater-than-one multipliers (or equivalently, a high marginal propensity to consume coupled with lots of dense sectoral linkages). With a multiplier greater than one, all government spending is magically transformed into “investment in Australian jobs”.

So the real question is: are multipliers actually greater-than-one? That’s an empirical question, and the answer is mostly no. (And if you don’t believe my neoliberal bluster, the progressive stylings of Ben Eltham over at Crikey more or less make the same point.)

But to get this you have to do the economics properly, and not just count the positive multipliers, but also account for the loss of investment in other sectors that didn’t take place because it was artificially re-directed into the film sector, which no commissioned impact study ever does.

This is why economists have a very low opinion of economic impact studies, which are to economics what astrology is to physics.

What does make for a good domestic film industry then? Look again at New Zealand, and look beyond the great Weta Studios in Wellington, for Australia and Canada both have world-class production studios and post-production facilities. Look beyond New Zealand’s natural scenery, for Vancouver is an easy match for New Zealand and Australia pretty much defines spectacular.

No, the simple comparison is that New Zealand is about 20% cheaper than Australia and 30% cheaper than Canada. New Zealand has lower taxes, easy employment conditions and relatively light regulations (particularly around insurance and health and safety). It’s just easier to get things done there.

If Australia really wants to boost its film industry, it might look more closely at labour market restrictions (including minimum wages) and regulatory burden and worry less about picking taxpayer pockets and bribing foreigners.

This article was originally published on The Conversation in December 2013. Read the original article. Republished under the a Creative Commons Attribution No Derivatives licence.

Recent Comments