Thinking of rent control? https://t.co/8IW3gS2idn via @JimRose69872629

— Jim Rose (@JimRosenz) August 16, 2018

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

16 Aug 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of bureaucracy, economics of regulation, law and economics, politics - New Zealand, property rights, Public Choice Tags: offsetting behaviour, rent control, unintended consequences

10 Jul 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, economics of regulation Tags: Harold Demsetz, racial discrimination, rent control

09 May 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of regulation Tags: rent control

07 May 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of regulation, Public Choice, rentseeking, television, urban economics Tags: rent control, Seinfeld

28 Apr 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, income redistribution, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: 2017 New Zealand election, offsetting behaviour, rent control, unintended consequences

Morgan wants to restrict the ability to evict tenants for reasons other than damage to the property and non-payment of rent. This includes not been able to evict a tenant on sale of the property.

We intend to change the regulations around residential tenancy law so leases make it far easier for a tenant to remain in the premises long term…

This will be achieved by restricting the conditions under which a landlord can evict a tenant to those of non-payment of rent or property damage. Sale of a property is not necessarily a legitimate reason for eviction. Tenants will be able to give 90 days notice.

That policy will make winding up of estates difficult. Houses will be have to be left vacant rather than rented while affairs are put in order. That is to name one of many flaws in a policy announced by a party that prioritises being different over been useful and right.

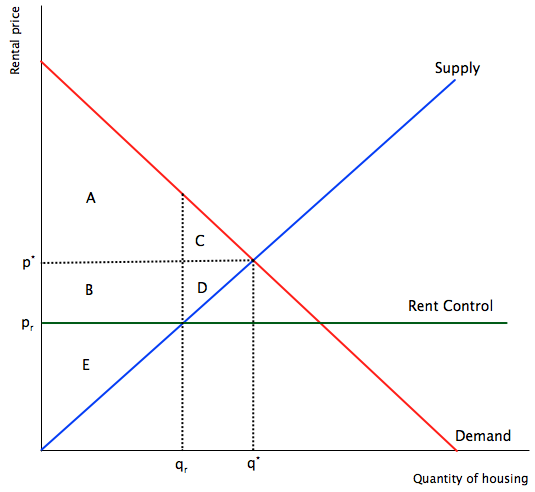

Source: RENTING Werner Z. Hirsch at encyclopedia of law and economics.

10 Jan 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economic history, economics of natural disasters, economics of regulation, Milton Friedman Tags: george stigler, rent control

06 Sep 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, television Tags: rent control, Seinfeld

05 May 2016 1 Comment

in David Friedman, economics of regulation, law and economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: avoiding difficult decisions, housing habitability laws, living standards, New Zealand Labour Party, offsetting, rent control, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge, unintended consequences

Source: David Friedman, Chapter 1: What Does Economics Have to Do with Law?

18 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, politics - USA, urban economics Tags: expressive voting, offsetting behaviour, rational ignorance, rational irrationality, rent control, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

10 Jul 2015 1 Comment

in applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, industrial organisation, labour economics, law and economics, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, property rights, survivor principle, urban economics Tags: consumer products standards, do gooders, economics of regulation, nanny state, offsetting behaviour, rent control, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, urban economics

The Government admits that its proposed insulation and smoke alarm standards for rental properties could push up rents by more than $3 a week. Under legislation to be introduced in October, social housing would have to be retrofitted with ceiling and underfloor insulation by next July, and all other rental homes by July 2019.

An important driver of lower quality housing in New Zealand is the restrictions on land supply. The costs of those restrictions, land makes up 60% of the cost of new houses rather than 40%. Land prices have doubled and tripled in a number of cities. As the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment has said:

The median price of sections has increased from $94,000 in 2003 to over $190,000 today (compared with $NZ 100,000 per section in the US), ranging from Southland ($82,000) to Auckland ($308,000)…

Section costs in Auckland account for around 60% of the cost of a new dwelling, compared with 40% in the rest of New Zealand.

The RMA is the Resource Management Act and was passed just before New Zealand housing prices started to rise rapidly.

Source: Dallas Fed; Housing prices deflated by personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator.

Higher land prices for new houses spill into the prices of existing houses, which are now much more expensive than they need to be but for the RMA inspired land supply restrictions in Auckland and elsewhere in New Zealand.

One way in which homeowners and landlords can keep costs down when buying a house either for their own use or as an investment property is not to invest in insulation and smoke alarms. Deposits are less, mortgages are less and rents are less. It all adds up.

$3 is not much for some but it is enough that some parents cannot find $3 or so per week to feed their children breakfast. Joe Trinder, the Mana News editor blogged about the great expense of feeding the kids for ordinary families.

Put simply, you cannot argue that a few dollars is a lot of money to people on low incomes but ignore the consequences for their welfare of a $3 per week increase in their rents.

If tenants were willing to pay for insulation, landlords would provide well-insulated rental properties to service that demand. Walter Block wrote an excellent defence of slumlords in his 1971 book Defending the Undefendable:

The owner of ghetto housing differs little from any other purveyor of low-cost merchandise. In fact, he is no different from any purveyor of any kind of merchandise. They all charge as much as they can.

First consider the purveyors of cheap, inferior, and second-hand merchandise as a class. One thing above all else stands out about merchandise they buy and sell: it is cheaply built, inferior in quality, or second-hand.

A rational person would not expect high quality, exquisite workmanship, or superior new merchandise at bargain rate prices; he would not feel outraged and cheated if bargain rate merchandise proved to have only bargain rate qualities.

Our expectations from margarine are not those of butter. We are satisfied with lesser qualities from a used car than from a new car.

However, when it comes to housing, especially in the urban setting, people expect, even insist upon, quality housing at bargain prices.

Richard Posner discussed housing habitability laws in his Economic Analysis of the Law. The subsection was titled wealth distribution through liability rules. Posner concluded that habitability laws will lead to abandonment of rental property by landlords and increased rents for poor tenants.

https://twitter.com/childpovertynz/status/618985237628858368

What do-gooder would want to know that a warranty of habitability for rental housing will lead to scarcer, more expensive housing for the poor! Surprisingly few interventions in the housing market work to the advantage of the poor.

Certainly, there will be less rental housing of a habitability standard below that demanded by do-gooders in the new New Zealand legislation. In the Encyclopaedia of Law and Economics entry on renting, Werner Hirsch said:

It would be a mistake, however, to look upon a decline in substandard rental housing as an unmitigated gain.

In fact, in the absence of substandard housing, options for indigent tenants are reduced. Some tenants are likely to end up in over-crowded standard units, or even homeless.

The straightforward way to increase the quality of housing in New Zealand without increasing poverty is to increase the supply of land.

As land prices fall, both homebuyers and tenants will be able to pay for better quality fixtures and fittings because less of their limited income is paying for buying or renting the land.

20 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, law and economics, property rights, Public Choice, rentseeking, Richard Posner Tags: Frank Easterbrook, rent control, Richard Posner

POSNER, Circuit Judge, with whom EASTERBROOK, Circuit Judge, joins in 819 F. 2d 732 – Chicago Board of Realtors Inc v. City of Chicago:

The stated purpose of the ordinance is to promote public health, safety, and welfare and the quality of housing in Chicago. It is unlikely that this is the real purpose, and it is not the likely effect.

Forbidding landlords to charge interest at market rates on late payment of rent could hardly be thought calculated to improve the health, safety, and welfare of Chicagoans or to improve the quality of the housing stock.

But it may have the opposite effect. The initial consequence of the rule will be to reduce the resources that landlords devote to improving the quality of housing, by making the provision of rental housing more costly. Landlords will try to offset the higher cost (in time value of money, less predictable cash flow, and, probably, higher rate of default) by raising rents. To the extent they succeed, tenants will be worse off, or at least no better off.

Landlords will also screen applicants more carefully, because the cost of renting to a deadbeat will now be higher; so marginal tenants will find it harder to persuade landlords to rent to them. Those who do find apartments but then are slow to pay will be subsidized by responsible tenants (some of them marginal too), who will be paying higher rents, assuming the landlord cannot determine in advance who is likely to pay rent on time. Insofar as these efforts to offset the ordinance fail, the cost of rental housing will be higher to landlords and therefore less will be supplied–more of the existing stock than would otherwise be the case will be converted to condominia and cooperatives and less rental housing will be built…

The provisions that authorize rent withholding, whether directly or by subtracting repair costs, may seem more closely related to the stated objectives of the ordinance; but the relation is tenuous. The right to withhold rent is not limited to cases of hazardous or unhealthy conditions. And any benefits in safer or healthier housing from exercise of the right are likely to be offset by the higher costs to landlords, resulting in higher rents and less rental housing.

The ordinance is not in the interest of poor people. As is frequently the case with legislation ostensibly designed to promote the welfare of the poor, the principal beneficiaries will be middle-class people.

They will be people who buy rather than rent housing (the conversion of rental to owner housing will reduce the price of the latter by increasing its supply); people willing to pay a higher rental for better-quality housing; and (a largely overlapping group) more affluent tenants, who will become more attractive to landlords because such tenants are less likely to be late with the rent or to abuse the right of withholding rent–a right that is more attractive, the poorer the tenant. The losers from the ordinance will be some landlords, some out-of-state banks, the poorest class of tenants, and future tenants.

The landlords are few in number (once owner-occupied rental housing is excluded–and the ordinance excludes it). Out-of-staters can’t vote in Chicago elections. Poor people in our society don’t vote as often as the affluent. See Filer, An Economic Theory of Voter Turnout 81 (Ph.D. thesis, Dept. of Econ., Univ. of Chi., Dec. 1977); Statistical Abstract of the U.S., 1982-83, at pp. 492-93 (tabs. 805, 806). And future tenants are a diffuse and largely unknown class.

In contrast, the beneficiaries of the ordinance are the most influential group in the city’s population. So the politics of the ordinance are plain enough, cf. DeCanio, Rent Control Voting Patterns,Popular Views, and Group Interests, in Resolving the Housing Crisis 301, 311-12 (Johnson ed. 1982), and they have nothing to do with either improving the allocation of resources to housing or bringing about a more equal distribution of income and wealth.

A growing body of empirical literature deals with the effects of governmental regulation of the market for rental housing. The regulations that have been studied, such as rent control in New York City and Los Angeles, are not identical to the new Chicago ordinance, though some–regulations which require that rental housing be "habitable"–are close. The significance of this literature is not in proving that the Chicago ordinance is unsound, but in showing that the market for rental housing behaves as economic theory predicts: if price is artificially depressed, or the costs of landlords artificially increased, supply falls and many tenants, usually the poorer and the newer tenants, are hurt…

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments