Figure 1: Weekly working hours needed at minimum-wage to move above a 50% relative poverty line after taxes, mandatory social or private contributions payable by workers, and family benefits for lone parent with two children, Anglo-Saxon countries, 2013

In which Anglo-Saxon country is full-time work not enough to escape family poverty on the minimum wage?

07 Jun 2015 1 Comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, population economics, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: earned income tax credit, poverty traps, single parents, taxation and the labour supply, welfare state

Which Anglo-Saxon country has the largest after-tax pay increase after a minimum wage increase?

06 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, welfare reform Tags: poverty traps, single parents, taxation and the labour supply, welfare reform, welfare state

Figure 1: Net gain after income taxes, Social Security contributions and benefit reductions after a 5% minimum wage increase for a lone parent family

Which Anglo-Saxon country has the highest after-tax minimum wage?

05 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, public economics Tags: Australia, British economy, Canada, Ireland, progressive taxation, taxation and the labour supply, welfare state

Figure 1: Minimum wage after income tax and social security contributions, US$ PPP, Anglo-Saxon countries, 2013

New Zealand does rather well on many measures of poverty and inequality

05 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: child poverty, family poverty, living wage, welfare state

Tough times? On #MayDay, compare % of low-paid #workers in yr country bit.ly/1EFrrV7 #LabourDay http://t.co/jNBrmjcom9—

(@OECD) May 01, 2015

Working for minimum wage? See how your country compares, then read oe.cd/mw2015 ( PDF) #wages http://t.co/DJsLYawtfw—

(@OECD) May 06, 2015

The futility of minimum wage increases as a poverty reduction strategy

31 May 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA, welfare reform Tags: family tax credits, poverty traps, welfare reform, welfare state

Hours worked per worker varies greatly across industrialised countries

20 May 2015 Leave a comment

Monday morning blues? Compare the avg number of #working hours in yr country per year. More: bit.ly/1JPVYQu http://t.co/r5MsELJr1n—

(@OECD) April 19, 2015

Health spending has been slow for a few years now

15 May 2015 Leave a comment

in health economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: public health expenditure, welfare state

Black and Hispanic poverty dropped by a third after the 1996 US welfare reforms

13 May 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: 1996 welfare reforms, child poverty, family poverty, welfare state

What’s left of the welfare state after dastardly neoliberalism still lifts most out of poverty

12 May 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA, poverty and inequality Tags: child poverty, family poverty, Leftover Left, neoliberalism, welfare reform, welfare state

How government reduces child poverty (SPM-measured) in the U.S. bit.ly/1D7eXjZ From: @aecfkidscount http://t.co/80m2jjXxvY—

Richard V. Reeves (@RichardvReeves) April 16, 2015

To tackle poverty, the Left says welfare, the Right says work. Guess what? They're both right: brook.gs/1zSabJI http://t.co/E4AZR05CQJ—

Richard V. Reeves (@RichardvReeves) February 13, 2015

The magic of (increasing) redistribution in one @EugeneSteuerle graph blog.metrotrends.org/2015/02/addres… http://t.co/lbtlM3zT5L—

Richard V. Reeves (@RichardvReeves) February 18, 2015

How the welfare state reduces inequality

11 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, labour economics, poverty and inequality Tags: poverty and inequality, top 1%, welfare reform, welfare state

How Gov. transfers (more than Federal taxes) reduce inequality cbo.gov/publication/49… http://t.co/3dMObjsykL—

Richard V. Reeves (@RichardvReeves) November 13, 2014

Swedosclerosis and the British disease compared, 1950–2013

03 May 2015 2 Comments

in economic growth, economic history, entrepreneurship, macroeconomics, Public Choice, public economics Tags: British disease, British economy, Margaret Thatcher, poor man of Europe, Sweden, Swedosclerosis, taxation and the labour supply, welfare state

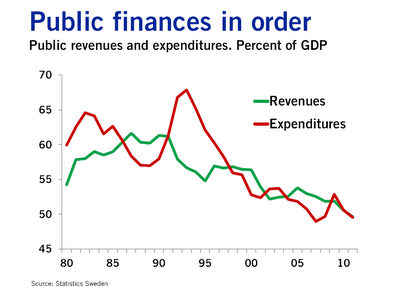

In 1970, Sweden was labelled as the closest thing we could get to Utopia. Both the welfare state and rapid economic growth – twice as fast as the USA for the previous 100 years.

Of course the welfare state was more of a recent invention. Assar Lindbeck has shown time and again in the Journal of Economic Literature and elsewhere that Sweden became a rich country before its highly generous welfare-state arrangements were created

Sweden moved toward a welfare state in the 1960s, when government spending was about equal to that in the United States – less that 30% of GDP.

Sweden could afford to expand its welfare state at the end of the era that Lindbeck labelled ‘the period of decentralization and small government’. Swedes in the 60s had the third-highest OECD per capita income, almost equal to the USA in the late 1960s, but higher levels of income inequality than the USA.

By the late 1980s, Swedish government spending had grown from 30% of gross domestic product to more than 60% of GDP. Swedish marginal income tax rates hit 65-75% for most full-time employees as compared to about 40% in 1960. What happened to the the Swedish economic miracle when the welfare state arrived?

In the 1950s, Britain was also growing quickly, so much so that the Prime Minister of the time campaigned on the slogan you never had it so good.

By the 1970s, and two spells of labour governments, Britain was the sick man of Europe culminating with the Winter of Discontent of 1978–1979. What happened?

Sweden and Britain in the mid-20th century are classic examples of Director’s Law of Public Expenditure. Once a country becomes rich because of capitalism, politicians look for ways to redistribute more of this new found wealth. What actually happened to the Swedish and British growth performance since 1950 relative to the USA as the welfare state grew?

Figure 1: Real GDP per Swede, British and American aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1950-2013, $US

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 1 is not all that informative other than to show that there is a period of time in which Sweden was catching up with the USA quite rapidly in the 1960s. That then stopped in the 1970s to the late 1980s. The rise of the Swedish welfare state managed to turn Sweden into the country that was catching up to be as rich as the USA to a country that was becoming as poor as Britain.

Figure 2: Real GDP per Swede, British and American aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, detrended, 1.9%, 1950-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 2 which detrends British and Swedish growth since 1950 by 1.9% is much more informative. The US is included as the measure of the global technological frontier growing at trend rate of 1.9% in the 20th century. A flat line indicates growth at 1.9% for that year. A rising line in figure 2 means above-trend growth; a falling line means below trend growth for that year. Figure 2 shows the USA growing more or less steadily for the entire post-war period. There were occasional ups and downs with no enduring departures from trend growth 1.9% until the onset of Obamanomics.

Figure 2 illustrates the volatility of Swedish post-war growth. There was rapid growth up until 1970 as the Swedes converged on the living standards of Americans. This growth dividend was then completely dissipated.

Swedosclerosis set in with a cumulative 20% drop against trend growth. The Swedish economy was in something of a depression between 1970 and 1990. Swedish economists named the subsequent economic stagnation Swedosclerosis:

- Economic growth slowed to a crawl in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Sweden dropped from near the top spot in the OECD rankings to 18th by 1998 – a drop from 120% to 90% of the OECD average inside three decades.

- 65% of the electorate receive (nearly) all their income from the public sector—either as employees of government agencies (excluding government corporations and public utilities) or by living off transfer payments.

- No net private sector job creation since the 1950s, by some estimates!

Prescott’s definition of a depression is when the economy is significantly below trend, the economy is in a depression. A great depression is a depression that is deep, rapid and enduring:

- There is at least one year in which output per working age person is at least 20 percent below trend; and

- there is at least one year in the first decade of the great depression in which output per working age person is at least 15 percent below trend; and

-

There is no significant recovery during the period in the sense that there is no subperiod of a decade or longer in which the growth of output per working age person returns to rates of 2 percent or better.

The Swedish economy was not in a great depression between 1970 and 1990 but it meets some of the criteria for a depression but for the period of trend growth between1980 and 1986.

Between 1970 and 1980, output per working age Swede fell to 10% below trend. This happened again in the late 80s to the mid-90s to take Sweden 20% below trend over a period of 25 years.

Some of this lost ground was recovered after 1990 after tax and other reforms were implemented by a right-wing government. The Swedish economic reforms from after 1990 economic crisis and depression are an example of a political system converging onto more efficient modes of income redistribution as the deadweight losses of taxes on working and investing and subsidies for not working both grew.

The Swedish economy since 1950 experienced three quite distinct phases with clear structural breaks because of productivity shocks. There was rapid growth up until 1970; 20 years of decline – Swedosclerosis; then a rebound again under more liberal economic policies.

The sick man of Europe actually did better than Sweden over the decades since 1970. The British disease resulted in a 10% drop in output relative to trend in the 1970s, which counts as a depression.

There was then a strong recovery through the early-1980s with above trend growth from the early 1980s until 2006 with one recession in between in 1990. So much for the curse of Thatchernomics?

After falling behind for most of the post-war period, the UK had a better performance compared with other leading countries after the 1970s.

This continues to be true even when we include the Great Recession years post-2008. Part of this improvement was in the jobs market (that is, more people in work as a proportion of the working-age population), but another important aspect was improvements in productivity…

Contrary to what many commentators have been writing, UK performance since 1979 is still impressive even taking the crisis into consideration. Indeed, the increase in unemployment has been far more modest than we would have expected. The supply-side reforms were not an illusion.

John van Reenen goes on to explain what these supply-side reforms were:

These include increases in product-market competition through the withdrawal of industrial subsidies, a movement to effective competition in many privatised sectors with independent regulators, a strengthening of competition policy and our membership of the EU’s internal market.

There were also increases in labour-market flexibility through improving job search for those on benefits, reducing replacement rates, increasing in-work benefits and restricting union power.

And there was a sustained expansion of the higher-education system: the share of working-age adults with a university degree rose from 5% in 1980 to 14% in 1996 and 31% in 2011, a faster increase than in France, Germany or the US. The combination of these policies helped the UK to bridge the GDP-per-capita gap with other leading nations.

How to argue for welfare reform when sincerely arguing against the 1996 US Federal welfare reforms

28 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: 1996 US welfare reforms, female labour supply, labour demographics, welfare state

The share of single mothers without a high school degree with earnings rose from 49 percent to 64 percent between 1995 and 2000 but has since fallen or remained constant almost every year since then. At 55 percent, it’s now just slightly above its level in 1997, the first full year of welfare reform (see first graph).

TANF now serves only 25 of every 100 families with children that live below the poverty line, down from AFDC’s 68 of every 100 such families before the welfare law

Over the last 18 years, the national TANF average monthly caseload has fallen by almost two-thirds — from 4.7 million families in 1996 to 1.7 million families in 2013 — even as poverty and deep poverty have worsened.

The number of families with children in poverty hit a low of 5.2 million in 2000, but has since increased to more than 7 million. Similarly, the number of families with children in deep poverty (with incomes below half of the poverty line) hit a low of about 2 million in 2000, but is now above 3 million.

The employment situation for never-married mothers with a high school or less education — the group of mothers most affected by welfare reform — has changed dramatically over the last several decades.

In the early 1990’s, when states first made major changes to their cash welfare programs, only about half of these mothers worked.

Importantly, there was a very large employment gap between the share of these never-married mothers and single women without children with similar levels of education, suggesting that there was substantial room for these never-married mothers to increase their participation in the labour force.

By 2000, the employment gap between these two groups of women closed, and it has remained so. But in the years since, the employment rate for both groups has fallen considerably.

The employment rate for never-married mothers is now about the same as when welfare reform was enacted 18 years ago. This suggests that the economy and low education levels are now the causes of limited employment among never-married mothers — not the availability of public benefits or anything particular to never-married mothers.

The Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities, who hail clearly from the Left of American politics, scrupulously documented the following:

- Big gains in the employment of single mothers until a setback in the Great Recession but is still much better than in 1996;

- Welfare dependency dropped by two thirds;

- Despite this two third drop in welfare dependency, and earnest predictions of acute poverty and deprivation made in 1996, the number of families in deep poverty has not changed, and the number of families in poverty fell significantly and only rose again with the Great Recession; and

- There was a dramatic increase in the percentage of never married mothers in employment, so much so that there is no difference in the employment rate of single women with no children and never married mothers!

Welfare dependency down by two thirds, employment of never married mothers up to levels no one thought possible, family poverty down, and economic independence is much more widespread and all because of the 1996 US Federal welfare reforms. That sounds like success to me – a great success.

via Chart Book: TANF at 18 | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Recent Comments