Bang Dang Nguyen and Kasper Meisner Nielsen looked at how share prices reacted to 149 cases of the chief executive or another prominent manager dying suddenly in American companies between 1991 and 2008.

If the shares rise on an executive’s death, he was overpaid; if they fall, he was not. Only 42% of the bosses studied were overpaid. Those with the bigger pay packages gave the best value for money as measured by the share-price slump when they passed away unexpectedly.

Share prices do speak to the value of the company and the contribution of its CEO. The share price of Apple went up and down by billions on the back of rumours about the health of Steve Jobs.

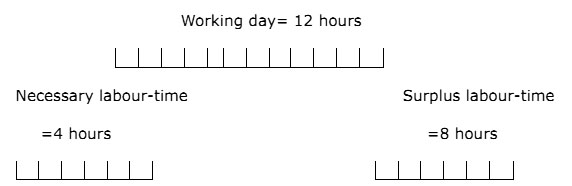

In terms of splitting of what some call the labour surplus increase from a firm hiring an executive, these employees retain on average about 71% and their employer keeps 29%. Others call this rent sharing.

71% going to the CEO might initially sound high, “but it’s not like he’s taking home more than he produced for the company,” says Nguyen.

The exploitation of CEOs gets worse when you consider the extensive use of promotion tournaments by their employers when setting their wages. They are thrust into rat races. Promotion tournaments are an integral and often invisible part of their workplaces.

Executive level employees are often ranked by their employers relative to each other and promoted not for being good at their jobs but for being better than their rivals. These promotion tournaments sent one employee against another – one worker against another – to the profit of the owners of the firm.

The rat race set up by the owners of the firm are so cutthroat that in competitions to determine promotions the capitalists who own the firm may find that their employees discover that the most efficient way of winning a promotion is by sabotaging the efforts of their rivals.

Lazear and Rozen’s tournament theory of executive pay has stood the test of time. The key to this rat race is the larger is your boss’s pay, the bigger the motivation for you as an underling to work for a promotion. As Lazear wrote in his book, Personnel Economics for Managers

The salary of the vice president acts not so much as motivation for the vice president as it does as motivation for the assistant vice presidents.

Recent Comments