Figure 1: Real GDP per British and Irish aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1955-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

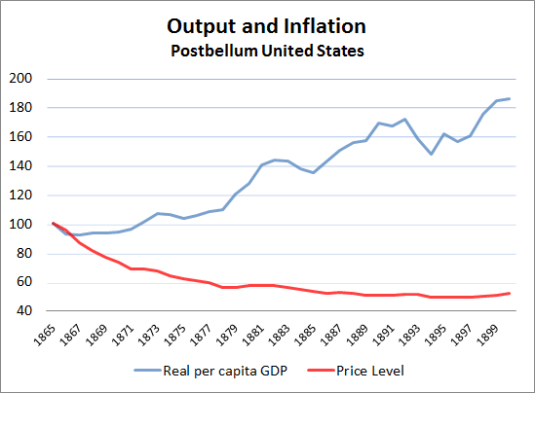

Figure 2 detrends British real GDP growth since 1955 by 1.9% and Irish real GDP growth by 3.6%. The US real GDP growth in the 20th century is used as the measure of the global technological frontier growing at trend rate of 1.9% in the 20th century. The Irish economy is more complicated story because its growth rate in figure 2 was detrended at a rate of 3.6% because it was catching up from a very low base. Trend GDP growth per working age Irish for 1960-73 was 3.6 per cent (Ahearne et al. 2006).

Figure 2: Real GDP per British and Irish aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1.9 per cent detrended UK, 3.6% detrended Ireland, 1955-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

A flat line in figure 2 indicates growth at 1.9% for that year. A rising line in figure 2 means above-trend growth; a falling line means below trend growth for that year.

In the 1950s, Britain was growing quickly that the Prime Minister of the time campaigned on the slogan you never had it so good.

By the 1970s, and two spells of labour governments, Britain was the sick man of Europe culminating with the Winter of Discontent of 1978–1979. What happened? The British disease resulted in a 10% drop in output relative to trend in the 1970s, which counts as a depression – see figure 2 .

Prescott’s definition of a depression is when the economy is significantly below trend, the economy is in a depression. A great depression is a depression that is deep, rapid and enduring:

- There is at least one year in which output per working age person is at least 20 percent below trend; and

- there is at least one year in the first decade of the great depression in which output per working age person is at least 15 percent below trend; and

- There is no significant recovery during the period in the sense that there is no subperiod of a decade or longer in which the growth of output per working age person returns to rates of 2 percent or better.

The British disease in the 1970s bordered on a depression. There was then a strong recovery through the early-1980s with above trend growth from the early 1980s until 2006 with one recession in between in 1990. So much for the curse of Thatchernomics?

Figure 1 suggests a steady economic course in Ireland until the 1990s with a growth explosion growth with the Irish converged on British living standards up until the global financial crisis.

Figure 2 shows the power of detrending GDP growth and why Ireland was known as the sick man of Europe in the 1970s and 1980s with unemployment as high as 18% and mass migration again. The Irish population did not grow for about 60 years from 1926 because of mass migration.

Figure 2 shows that real GDP growth per working age Irish dropped below its 3.6 per cent trend for nearly 20 years from 1974 , but more than bounced back after 1992. The deepest trough was 18 per cent below trend and the final trough was in 1992 – see Figure 2.

The deviation from trend economic growth made the Irish depression from 1973 to 1992 comparable in depth and length to the 1930s depressions (Ahearne et al. 2006).

The Irish depression of 1973 to 1992 can be attributed to large increases in taxes and government expenditure and reduced productivity (Ahearne et al. 2006). There were two oil price shocks in the 1970s and many suspect Irish policy choices from 1973 to 1987.

There were three fiscal approaches: an aggressive fiscal expansion from 1977; tax-and-spend from 1981; and aggressive fiscal cuts from 1987 onwards. In the early 1980s, Irish CPI inflation at 21 per cent, public sector borrowing reached 20 per cent of GNP.

To rein in budget deficits, taxes as a share of GNP rose by 10 percentage points in seven years. The unemployment rate reached 17 per cent despite a surge in emigration. The rising tax burden raised wage demands, worsening unemployment. Government debt grew on some measures to 130 per cent of GNP in 1986 (Honohan and Walsh 2002).

From 1992, Ireland rebounded to resume catching-up with the USA. The Celtic Tiger was a recovery from a depression that was preceded by large cuts in taxes and government spending from the late 1980s (Ahearne et al. 2006). Others reach similar conclusions but avoid the depression word. Fortin (2002, p. 13) labelled Irish public finances in the 1970s and to the mid-1980s as a ‘black hole’.

Fortin (2002) and Honohan and Walsh (2002) disentangle the Irish recovery into a long-term productivity boom that had dated from the 1950s and 1960s, and a sudden short-term output and employment boom since 1993 following the late 1980s fiscal and monetary reforms.

Honohan and Walsh (2002) wrote of belated income and productivity convergence. The delay in income and productivity convergence came from poor Irish economic and fiscal policies in the 1970s and 1980s.

This was after economic reforms in the late 1950s and the 1960s that started a process of rapid productivity convergence after decades of stagnation and mass emigration; Ireland’s population was the same in 1926 and 1971. During the 1950s, up to 10 per cent of the Irish population migrated in 10 years.

In the 1990s, many foreign investors started invested in Ireland as an export platform into the EU to take advantage of a 12.5 per cent company tax rate on trading profits. Between 1985 and 2001, the top Irish income tax rate fell from 65 to 42 per cent, the standard company tax from 50 to 16 per cent and the capital gains tax rate from 60 to 20 per cent (Honohan and Walsh 2002).

What happened after the onset of the global financial crisis in Ireland and the UK are for a future blog posts.

Recent Comments