Europe’s dismal economy

15 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, business cycles, Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics Tags: Euroland, Euros crisis

Romer and Romer vs. Reinhart and Rogoff – MoneyBeat – WSJ

01 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: financial crises, GFC

Identifying financial crises after the fact is problematic: researchers will disagree on what their characteristics were, when they started and ended, and what actually counts as a crisis. This is particularly true of crises before World War II or involving developing economies, for which accurate data are harder to come by.

So the Romers created a measure of financial distress based on real-time accounts of developed-economy conditions prepared semiannually by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development between 1967 and 2007. And to check that the OECD wasn’t for some reason off-base on conditions, they crosschecked it with central bank annual reports and articles in The Wall Street Journal.

They then scored the severity of financial conditions from zero to 15, thus avoiding quibbles over what is and isn’t a crisis and allowing for more precise readings of economic effects.

Their finding: Declines in economic output, as measured by gross domestic product and industrial production, following crises were on average moderate and often short-lived. There was a lot of variation in outcomes, so there was nothing cut and dried about how economies respond to crises…

via Romer and Romer vs. Reinhart and Rogoff – MoneyBeat – WSJ.

Romers’ work suggests the poor performance of economies around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis shouldn’t be cast as inevitable. In The Current Financial Crisis: What Should We Learn From the Great Depressions of the 20th Century? de Cordoba and Kehoe note that:

Kehoe and Prescott [2007] conclude that bad government policies are responsible for causing great depressions. In particular, they hypothesize that, while different sorts of shocks can lead to ordinary business cycle downturns, overreaction by the government can prolong and deepen the downturn, turning it into a depression.

An Open Letter to Paul Krugman | David K. Levine

31 Oct 2014 3 Comments

in budget deficits, business cycles, comparative institutional analysis, economics of religion, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics

David Friedman on the causes of the global financial crisis and the great recession

16 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

Earl A. Thompson on fiscal and monetary policy in the Great Recession

09 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, fiscal policy, great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: crowding out, Earl A. Thomson, fiscal policy, great depression, great recession, permanent income hypothesis, Ricardian equivalence

Eugene Fama and the simulative effects of fiscal policy

31 Jul 2014 6 Comments

in budget deficits, fiscal policy, great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: crowding out, Eugene Fama, fiscal policy, Treasury view of fiscal policy

Eugene Fama argues that government bailouts and stimulus plans seem attractive when there are idle resources – when there is unemployment such as in a recession or depression including in the 1930s.

Fama counters that:

1. Bailouts and stimulus plans must be financed.

2. If the financing takes the form of additional government debt, the added debt displaces other uses of the funds.

3. Thus, stimulus plans only enhance incomes when they move resources from less productive to more productive uses.

In the end, despite the existence of idle resources, bailouts and stimulus plans do not add to current resources in use. They just move resources from one use to another.

Fama noted that there was just one valid negative comment in response to this argument that appears to be valid which was made by Brad DeLong.

Fama thinks Delong’s point about involuntary inventory accumulation is consistent with Fama’s initial arguments about the need for the stimulus to work through moving resources to higher value uses.

For me, the notion that a fiscal stimulus is a negative productivity shock is a good starting point for analysis. The method of financing the stimulus is important too.

Economic agents know that a temporary expenditure program has no lasting effect on employment but has lasting effect on disposable income and taxes. Indeed, massive public interventions to maintain employment and investment during a financial crisis can, if they distort incentives enough, lead to a depression.

In Australia, there was a massive fiscal contraction from late 1930 onwards called the Premiers’ Plan. In 1931, unemployment rates was 25% or more.

- The Premiers’ Plan required the federal and state governments to cut spending by 20%, including cuts to wages and pensions and was to be accompanied by tax increases, reductions in interest on bank deposits and a 22.5% reduction in the interest the government paid on internal loans.

- The Premiers’ Plan was complementary to the Arbitration Court’s 10 per cent nominal wage cut in January 1931 and the devaluation of the Australian pound. Most countries had abandoned the gold standard by 1931 and 1932 and devalued by about 10% including the UK. These competitive devaluations were called currency wars. Most countries below started to recovery before they left the gold standard, a year or two before they left the cross of gold.

Maclaren (1936) dated the Australian economic recovery from the last months of 1932. It was to take another three years before unemployment rates fell below 10 per cent — the rate it had been during most of the 1920s.

The June 1931 Premiers’ Plan of fiscal consolidation had time by late 1932 to become credible and take hold given the usual leads and lag on fiscal policy. Unemployment data for the time show a rapid fall in the high twenties unemployment rate in 1932 to be below 10 per cent by 1937.

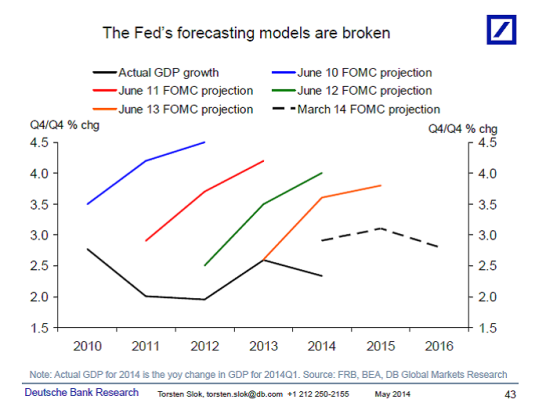

Groundhog Day for economic forecasters – The Grumpy Economist

13 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in economic growth, great recession Tags: forecasting errors, John Cochrane

Robert Lucas explained his support for U.S. monetary policy in 2008 as follows

10 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, Robert E. Lucas Tags: fiscal policy, GFC, monetary policy, Robert Lucas

- There are many ways to stimulate spending, but monetary policy was the most helpful counter-recession action because it was fast and flexible.

- There is no other way that so much cash could have been put into the system as fast, and if necessary it can be taken out just as quickly. The cash comes in the form of loans.

- There is no new government enterprises, no government equity positions in private enterprises, no price fixing or other controls on the operation of individual businesses, and no government role in the allocation of capital across different activities. These were important virtues.

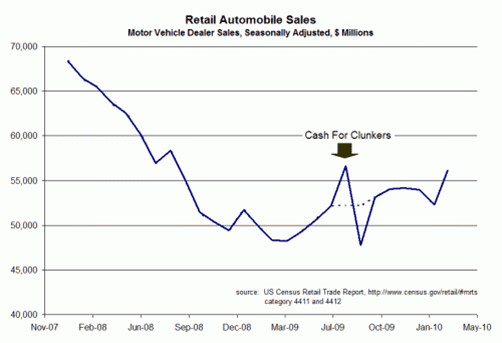

Did “Cash for Clunkers” work?

07 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in great recession, macroeconomics Tags: cash for clunkers, intertemporal consumption smoothing, permanent income hypothesis

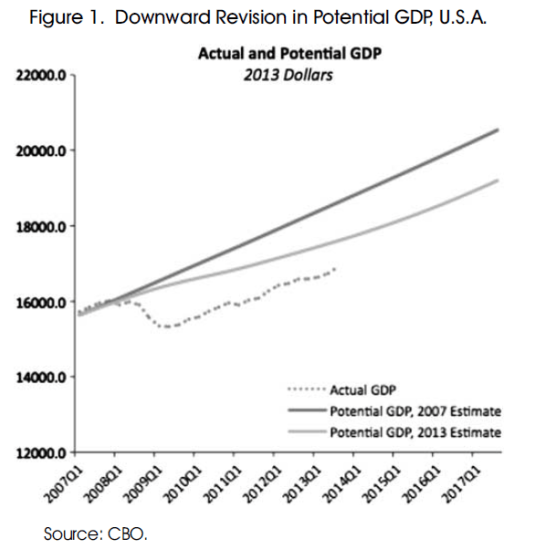

Actual and potential GDP in the USA

26 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

Crony capitalism flashback – who voted against the TARP in 2008?

20 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in financial economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, rentseeking Tags: crony capitalism, TARP

The US House of Representatives initially voted down the TARP in a grand coalition of right-wing republicans and left-wing democrats, voting 205–228. The right-wing republicans opposed the bailout because capitalism is a profit AND loss system. Democrats voted 140–95 in favour of the Bill while Republicans voted 133–65 against it.

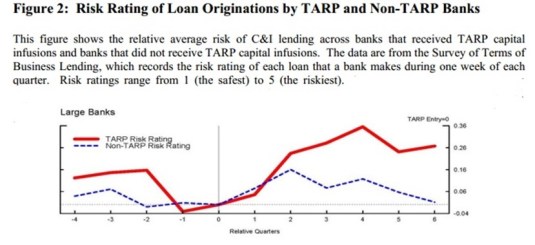

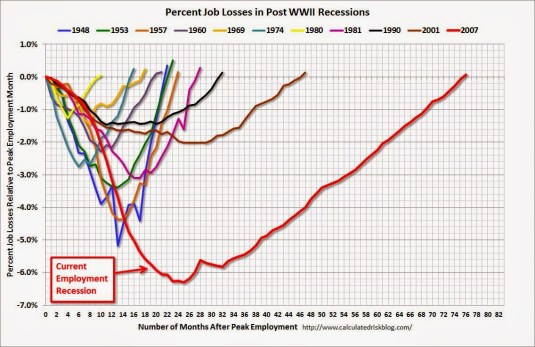

The chart above shows that the degree of risk in commercial loans made by TARP recipients appears to have increased. This is no surprise. In the 1960s, Sam Peltzman published a paper in in the 1960s showing that when deposit insurance was introduced in the USA in the 1930s, the banks halve their capital ratios. They did not need to have as much capital as before to back their lending. The chart below shows that the TARP really didn’t do much for economic policy uncertainty.

In an open letter sent to Congress, over 100 university economists described three fatal pitfalls in the TARP:

1) Its fairness. The plan is a subsidy to investors at taxpayers’ expense. Investors who took risks to earn profits must also bear the losses. The government can ensure a well-functioning financial industry without bailing out particular investors and institutions whose choices proved unwise.

2) Its ambiguity. Neither the mission of the new agency nor its oversight is clear. If taxpayers are to buy illiquid and opaque assets from troubled sellers, the terms, timing and methods of such purchases must be crystal clear ahead of time and carefully monitored afterwards.

3) Its long-term effects. If the plan is enacted, its effects will be with us for a generation. For all their recent troubles, America’s dynamic and innovative private capital markets have brought the nation unparalleled prosperity. Fundamentally weakening those markets in order to calm short-run disruptions is will short-sighted.

A recent IMF study of 42 systemic banking crises showed that in 32 cases, there was government financial intervention.

Of these 32 cases where the government recapitalised the banking system, only seven included a programme of purchase of bad assets/loans (like the one proposed by the US Treasury). These countries were Mexico, Japan, Bolivia, Czech Republic, Jamaica, Malaysia, and Paraguay.

The Government purchase of bad assets was the exception rather than the rule in banking crises and rightly so. The TARP mostly benefited bank shareholders. A case of privatising the gains and socialising the losses from banking was passed on the votes of Congressional Democrats.

Recent Comments