Source: The Sanders campaign is living in an economic fantasy world.

And people vote for @BernieSanders because he is honest

21 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in fiscal policy, income redistribution, macroeconomics, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking Tags: 2016 presidential election, cranks, quackery, rational ignorance, rational irrationality

Commercial evaluation of KiwiRail, Solid Energy and total SOE portfolio in New Zealand since 2007

20 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in fiscal policy, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, public economics Tags: government ownership, privatisation, state owned enterprises

Two dogs of an investment propped up a $20 billion portfolio that a few years later was worth less than 1/5 of that. Both of these stalwarts are now worth not even one dollar.

Source:New Zealand Treasury – information released under the Official Information Act, January 2016.

Smoking – where are the externalities?

19 Feb 2016 2 Comments

in applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, health economics, politics - New Zealand, public economics

It will be a slow train coming before the Morgan Foundation calls for a cut in the tobacco tax because the optimal Pigovian tax on it is already too high from the perspective of externalities or the burden on the public health budget.

Source: Cigarette Taxation and the Social Consequences of Smoking | Heartland Institute.

I think smoking is disgusting and unhealthy but that does not give me the right to regulate the disgusting habits of others. Where would I start in regulating risk-taking? I would have to start with swimming, tramping and biking. They are all high-risk activities of the self-righteous? Not everything others do that I do not like causes an externality.

Few economists work on the economics of smoking other from the starting point that it should be reduced. Those that do not share that starting point such as Robert Tollison, Gary Anderson and William Shughart are subject to relentless personal abuse. They are immediately denounced as the paid whores of the tobacco industry.

That was one of the reasons I got interested in the economics of smoking. There must be something in the case made by Robert Tollison and others questioning tobacco taxes if the first line of argument against them is you are saying that because someone paid, you low down dog.

NZ state-owned enterprise dividends & cash injections since 2007 – updated

18 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, public economics Tags: government ownership, KiwiRail, New Zealand Greens, New Zealand Labor Party, privatisation, rational irrationality, state owned enterprises

With a straight face, the Labour Party and the Greens claim that state-owned enterprises should not be sold because taxpayers give up the future dividend stream.

Source: New Zealand Treasury – data released under the Official Information Act.

Leaving to one side what the sale price is the net present value of, for as far back as I could obtain data from the Treasury, it is a rare year in which the taxpayers does not pour more money into state-owned enterprises than they get back in dividends.

Transpower is carrying the entire state-owned enterprise portfolio. Earlier on, Solid Energy – a now bankrupt coal mining company– was carrying the portfolio in terms of cash flow to the taxpayer.

KiwiRail commercial valuation since 2007 @JordNZ @dpfdpf

18 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in industrial organisation, politics - USA, public economics Tags: KiwiRail, privatisation, state owned enterprises

Does @nztreasury understand company tax incidence?

18 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, politics - New Zealand, public economics

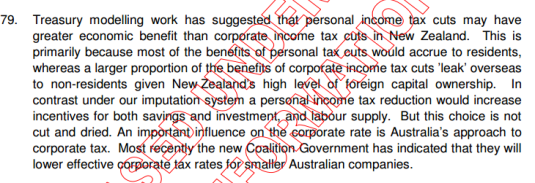

The New Zealand Treasury understands neither who pays company taxes when capital is internationally mobile nor why Ireland was relentlessly bullied over its 12.5% company tax rate.

The Treasury makes the surprising claim that the benefits of company tax cuts will leak overseas to non-residents because of the high level of foreign capital ownership.

Now if New Zealand were to substantially cut its company tax rate, hell will freeze over before the Australian Treasurer rings up and say thanks mate. The Australian worry will be the loss of investment and corporate headquarters to New Zealand.

Who pays company tax when capital is internationally mobile is one of the easiest questions you can get in an economics quiz. Just trace out how investors will react to a lower company tax in New Zealand.

If company taxes are lower in New Zealand, more investment will flow into New Zealand, increasing the size of the capital stock in New Zealand and with it wages in New Zealand because New Zealand workers have more capital to work with.

When will these international capital inflows stop? It is obvious! When risk-adjusted after-tax returns equalise for internationally mobile investors. They will adjust their portfolios so that after-tax returns equalise across tax jurisdictions.

The after-tax returns are equalised by the competing tax jurisdictions having different before-tax rates of return on capital and therefore costs of capital.

Jurisdictions with high company taxes have to offer larger before-tax returns so that internationally mobile investors receive the same risk-adjusted after-tax return everywhere. High tax jurisdictions boost before tax return by wages being lower in the high tax jurisdiction.

High company taxes are paid for by the workers of the jurisdiction concerned through having to accept lower wages to work with the same amount of capital. They must compensate foreign investors by boosting before-tax returns so that their after-tax rates of return equalise across competing tax jurisdictions.

The New Zealand Treasury missed this most basic point about who pays a company tax in a globalised world. The Australian Treasury is right on top of this basic piece of economics:

The mobility of capital refers to how easily financial capital (debt and equity) flows into and out of a country. Greater capital mobility will shift more of the burden of taxation from capital to labour through larger changes in the domestic capital stock, and hence in domestic labour productivity and wages (Grubert and Mutti 1985; Gravelle 2010).

In this situation, a reduction in the company tax rate will result in large inflows of foreign capital to ensure that there is no material difference between the after tax (risk adjusted) rate of return on investment in Australia and the rate available abroad.

The many attempts at company tax harmonisation by the European Union and G20 are motivated by the fear of large capital flows into the lower tax jurisdictions.

No high-tax country views the low company taxes in Ireland, Singapore and Hong Kong as a windfall where they can raise more tax revenue on the additional dividends repatriated from lower tax jurisdictions.

Very large economies such the USA can get away with a slightly above average rates of company tax because the number of other places to go are fewer.

A small open economy such as New Zealand should safely assume that most to all of burden of the company tax is on New Zealand workers through lower wages.

Capital migrates from high-tax to low-tax locations, reducing capital-to-labour ratios in high-tax countries. The low-tax countries experience higher capital-to-labour ratios, a higher marginal product of labour, and higher wages.

I will be putting in an Official Information Act request seeking to find out whether the work of Arnold Harberger influences their company tax briefings to ministers. I will also add any work they are done on corporate inversions and the company tax rate in Ireland.

@EconomicPolicy’s strangest yet case for the #livingwage @Mark_J_Perry

17 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - USA, public economics

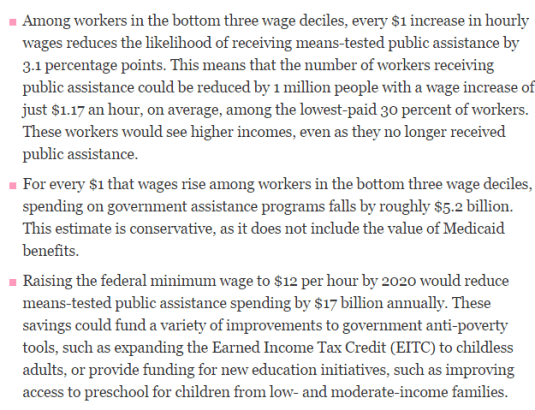

In a bizarre twist, the Economic Policy Institute is spinning one of the strongest arguments against minimum wage increases into an argument for them.

The Economic Policy Institute pointed out this week that raising the minimum wage saves billions because public assistance to low-paid workers is wound back as their wages rise.

A bog standard argument against minimum wage rises is the take-home pay of low paid workers will rise by much less than the rise in labour costs to their employers.

The reason for that discrepancy between before and after-tax pay is cash and non-cash assistance from government reduces as their wages rise with the minimum wage increase.

It is pretty standard for effective marginal tax rates and low-paid workers to be high because of the many forms of assistance in cash and in-kind which they receive winds back as their wages rise.

Working Class American Families Face Marginal #Tax Rates up to 43.7% bit.ly/1IGqQqE @ScottElliotG https://t.co/zJwIfrp2pT—

Tax Foundation (@taxfoundation) January 04, 2016

There is a large literature on the labour supply effects of this winding back of family tax credits and other assistance to low-paid as their earnings increase.

The poverty trap facing welfare beneficiaries and the low-paid because of this winding back of family tax credits and other social assistance is so widely accepted that is the only time that the Left believes in supply-side economics. It is one of the reasons for their enthusiasm for a universal basic income.

Because of the interaction between wage rises and social assistance, the practical upshot is the job of the low-paid worker is put at risk by the minimum wage increase and yet their take-home pay increases by much less. Some will lose their jobs. Others will not be hired in the first place.

Jens Rushing's perfect response to #RaiseTheWage critics went viral this summer. Read it: attn.com/stories/2619/e… https://t.co/KBIM5XLKmz—

The Fairness Project (@ProjectFairness) November 06, 2015

Almost 20 years ago, Paul Krugman pondered on why supporters of the minimum wage was so adamant that their before-tax wage must increase rather than their incomes be supplemented by family tax credits and other social assistance. He asked:

…why take this route? Why increase the cost of labour to employers so sharply, which–Card/Krueger notwithstanding–must pose a significant risk of pricing some workers out of the market, in order to give those workers so little extra income? Why not give them the money directly, say, via an increase in the tax credit?

In his book review, Krugman nailed it when he concluded that the demands for a higher minimum wages about morality:

…I suspect there is another, deeper issue here-namely, that even without political constraints, advocates of a living wage would not be satisfied with any plan that relies on after-market redistribution. They don’t want people to “have” a decent income, they want them to “earn” it, not be dependent on demeaning handouts…

In short, what the living wage is really about is not living standards, or even economics, but morality. Its advocates are basically opposed to the idea that wages are a market price–determined by supply and demand, the same as the price of apples or coal.

And it is for that reason, rather than the practical details, that the broader political movement of which the demand for a living wage is the leading edge is ultimately doomed to failure: For the amorality of the market economy is part of its essence, and cannot be legislated away.

The advocates of the living wages simply offended by the notion of people earning so little. I am less kind than Krugman to this moralising.

These do-gooders are perfectly willing to put the jobs of the low-paid at risk so that they are not offended by how little they have paid.

In the finest traditions of rational irrationality and expressive voting, they simply deny they are putting jobs at risk and going into terribly convoluted arguments about how the employment effects of be small and everyone are we better off and more productive. Arguments that Paul Krugman laughed at back in 1998.

Living wage advocates are not using the low-paid for policy experiments, which would be pretty bad, they use them to make themselves feel better about the inequalities of the world. They just want to drive the sinners out of the temple come what may.

Once were Sweden! New Zealand, Swedish and Australian general government expenditure as % of GDP since 1986

12 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economic growth, economic history, fiscal policy, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, public economics Tags: Australia, growth of government, lost decades, size of government, Sweden

I came across this data showing that New Zealand and Sweden had the same sized public sectors in the mid-1980s some years ago. The data could not be found again for a long time in the OECD statistical databases. One reason was the OECD changed its name to general disbursements.

Data extracted on 12 Feb 2016 08:45 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

The size of the public sector in Australia has not changed much for 30 odd years. The public sector has been in a long decline in Sweden and New Zealand since peaks as a percentage of nominal GDP in the late 1980s and early 1990s respectively.

I know of no comments on the large size of the New Zealand public sector as measured by general government expenditure in the late 1980s. Its contribution to the stagnant economic growth of that time is worth exploring.

PMG radio & TV licences (Frank Thring)

11 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, economics of media and culture, economics of regulation, public economics

HT: Antony Green.

The only time that the left become supply-side economists

10 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, Public Choice, public economics Tags: povertytraps, taxation and labour supply

Recent Comments