Piketty and Capital Taxation in the 21st Century

20 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economic growth, economic history, income redistribution, macroeconomics, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking Tags: Leftover Left, Thomas Piketty

Zombie lending and lower Japanese productivity growth

15 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in economic growth, macroeconomics, politics - New Zealand, public economics Tags: fiscal stimulus, Japan, Lost Decade, Think Big

The low Japanese productivity growth throughout the 1990s could have been the result of subsidies to inefficient firms and declining industries both directly and through a banking system rolling over loans in arrears to insolvent firms.

This policy is known as zombie lending, and it lowered productivity because higher cost firms kept producing a greater share of Japanese output than would otherwise have been the case (Hayashi and Prescott 2003; Ahearne and Shinada 2005).

- Zombie firms are insolvent firms often propped up with new loans and loan rollovers from Japanese banks.

- Zombie banks are insolvent banks propped up with loans from the central bank and by lax regulatory inspections of their weak loan portfolios and lack of adequate capital.

Japan’s economic policies have until recently kept insolvent banks operating, further encouraging zombie lending, which impeded the flow of capital to the more efficient firms.

The competitive process where zombies shed workers and lose market share was thwarted. The Japanese authorities subsidised insolvent banks and firms and provided credit to some firms and not to others (Prescott 2002; Hayashi and Prescott 2002; Caballero et al. 2005; Hoshi and Kashyap 2004).

The pervasiveness and long-term persistence of zombie lending as a shock to Japanese productivity growth cannot be understated. As Kashyap noted:

The government allowed even the worst banks to continue to attract financing and support their insolvent borrowers

…By keeping these unprofitable borrowers alive, banks allowed the zombies to distort competition throughout the rest of the economy.

Caballero et al. (2008) estimated that 30 per cent of all publicly traded Japanese manufacturing, construction, real estate, retail, wholesale, and service sector firms were on life support from banks in the early 2000s, and that most large Japanese banks only complied with capital standards because regulators were lax in their inspections.

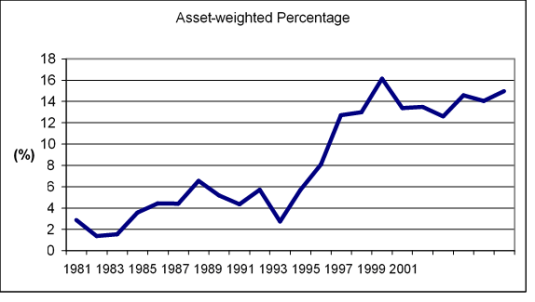

The percentage of zombies hovered between 5 and 15 per cent up until 1993 and rose sharply over the mid-1990s to exceed 25 per cent for every year after 1994 (Caballero et al. 2008).

Figure 1: Prevalence of Firms Receiving Subsidized Loans in Japan

Source: Caballero et al. (2008) Zombie Lending and Depressed Restructuring in Japan. American Economic Review.

Zombie lending is a more serious problem for Japanese non-manufacturing firms than for manufacturing firms (Caballero et al. 2008). Small and medium size firms were also major beneficiaries of zombie lending.

Zombie lending also discourages new investments that increase Japanese productivity, encourages inefficient firms to avoid making the decisions necessary to raise their profitability, and impedes the solvent Japanese banks from finding good lending opportunities (Caballero et al. 2008; Sekine et al. 2003). As Kashyap noted:

Usually when an industry is hit by a bad shock, many firms exit… In Japan, firms never exited. Given that they never exited, it is not surprising that new firms weren’t created.

Under normal conditions, higher cost firms would go bankrupt and be replaced by new and better ideas and firms. Instead, firms that were more efficient than the zombie firms tended to exit industries because their demise does not require the banks to acknowledge large bad loans. This exit of the firms of intermediate efficiency rather than the exit of the least efficient firms dragged productivity down even further (Nishimura et al. 2005; Okana and Horioka 2008). New Zealand in the 1970s and in the early 1980s also had a range of policy measures that supported high-cost firms and declining industries.

When bankrupt firms can stay in business, they retain workers who otherwise would be willing to work for lower wages at a healthy firm and depress market prices for their products. Low prices and high wages reduce the profits that more productive firms can earn which discourages entry and investment.

The creation of new jobs is a measure of industry dynamism. In manufacturing, which suffered the least from the zombie problem, job creation hardly changed from the early 1990s to the late 1990s. In contrast, there was a large decline in job creation in the non-manufacturing sectors, particularly in construction (Caballero et al. 2008; Hoshi 2006; Caballero et al. 2008).

There was less restructuring of employment and market shares in favour of the more productive firms. The gap in productivity growth between the Japanese manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors more than doubled over the 1990s (Caballero et al. 2008).

Japanese R&D spending has also slowed down significantly since the start of the 1990s (Comin forthcoming). The gap in the rate of computer adoption between Japan and USA also increased in the 1990s. The speed of diffusion of new technologies slowed to the point that South Körea has now surpassed Japan in the diffusion of computers and the Internet (Comin forthcoming).

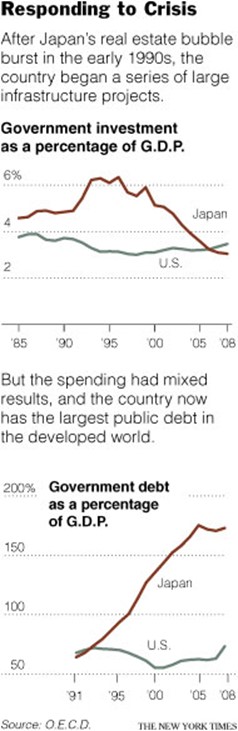

Over the 1990s, there were ten massive fiscal packages to maintain employment and investment. Much of this additional Japanese government spending was on public works and other projects whose social payoffs have been queried by independent observers. The consumption tax was increased from 3 per cent to 5 per cent in 1997. There were two rounds of temporary tax cuts – for 2 years only.

Japan pursued economic policies in response to a recession that stifled total factor productivity by providing bad incentives to the private sector.

The unproductive firms depressed Japanese productivity because they competed for labour and capital that could have been used by the more productive firms. Zombie lending allowed many firms to stay in business long after the monetary policy changes that uncovered their unprofitable petered out. The diversion of resources to these insolvent firms prevented a productivity recovery. The lack of a productivity recovery depressed wages, incomes and consumer demand.

The zombie lending and fiscal packages compounded the 1990 monetary contraction into the highly persistent shocks that were required to be able to depress Japanese productivity growth for more than a decade.

More and more resources were tied up in high cost firms and in declining industries. This was rather than be reallocated to more productive uses by the normal market processes of relative price and wage changes, free entry and profit and loss. Kashyap argues that:

The experience in Japan definitely shows that providing subsidized credit to dying firms will be costly over time. Keeping an industry from restructuring only delays the day of reckoning and raises the cost substantially

…There are many examples besides Japan where people fail to recognize that it is dangerous to keep people attached to businesses that are fundamentally unprofitable

The massive Japanese government investments have echoes of the ‘Think Big’ energy investments in New Zealand in the late 1970s.

The productivity impact of ‘Think Big’ was suspect. In addition, state-owned enterprises offering a net return of zero to the Crown in the 1980s has Japanese parallels.

The propping up of high cost state owned and private firms in the 1970s and 1980s in New Zealand helped to depress productivity growth rates. State-owned enterprises offered a net return of about zero to the taxpayer, even as recently as last year in New Zealand.

More and more resources were tied up in New Zealand in the high cost firms and declining industries than be reallocated to more productive uses by the market processes of price and wage changes, free entry and profit and loss. The lack of productivity growth depressed wages, incomes and consumer demand in New Zealand.

The productivity based explanations for the slumps in New Zealand from 1974 to 1992 and in Japan from 1990 to 2003 have a number of common threads.

Trends in average marginal tax rates in the USA

05 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, political change, politics - USA, public economics Tags: Marginal tax rates, tax reform, taxation and the labour supply

Tom Sargent’s Keynote Address BYU CPEC 2012 on taxation and redistribution

11 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in fiscal policy, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, public economics Tags: taxation and the labour supply, Tom Sargent

Is welfare dependence optimal for whom – part 4: In-work tax credits and labour supply

10 Dec 2014 3 Comments

in labour economics, labour supply, public economics, welfare reform Tags: Labour leisure trade-off, welfare dependency, welfare reform

In-work tax credits were introduced in many countries including New Zealand to encourage movement into employment by breadwinners. By linking a large payment with full-time and semi-full-time work, the rewards for working are increased for single parents and families. These in work tax credits combined child tax credit with an in work tax credit for the sole mother or couple.

These in-work benefits can phase-in when a minimum income level is reach such as with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the USA, or a paid in full when a minimum number of hours are worked. The Working for Families in-work tax credit in New Zealand and the UK family tax credit are two examples where there is a large cash payment with no phasing-in:

- Working for Families in New Zealand is paid if 30 hours are worked by New Zealand families or 20 hours are worked by sole parents; and

- The British family tax credit was paid if 16 hours are worked, initially 24 hours per week.

Figure 1 shows the impact of the introduction of an in-work tax credit paid in full to families and sole parents if a minimum number of hours per week are worked by a family or sole parent. There is no phase-in region such as with the earned income tax credit (EITC) in the USA.

Figure 1: In work tax credits and labour supply

The in-work tax credit phases-out after once the family’s income increases past an income threshold. This income threshold is usually linked to the number of children as well.

An in-work family tax credit linked to a high number of minimum number of hours worked provides an incentive for those not in work to increase their hours worked by a large amount and leave welfare, as is shown by arrow 1 in Figure 1.

For those already work, the income and substitution effect cut against each other and their net effect depend on the number of hours currently worked.

- Those working a low number of hours, hours less per week than the minimum to qualify for the in-work tax-credit have an incentive to increase their hours to the minimum to qualify and leave welfare is shown by arrow 2 in Figure 1.

- Arrows 3 and 4 in Figure 1 both represent reduction in hours worked.

- Some workers can take-home more pay and work fewer hours per week or per year as shown by arrow 3.

- Other high working hours worker can enjoy more leisure time at the expense of a slightly reduced take-home pay as shown by arrow 4.

The net labour supply effects of an in-work tax credit are therefore ambiguous because of these multiplicity of labour supply effects with some people working more another’s work in letters.

There will also be a bunching of hours worked at around the eligibility point for paying the in-work tax credit. The eligibility point is usually grouped around working a minimum of three or four days per week part or full-time that sum to 30 hours for families and 20 hours for sole parents.

Workers working less that the weekly working hour minimums will increase to the minimum to qualify for the family tax credit. Workers working more than the minimum required to qualify for the family tax credit might cut back to the working hours minimum because of the superior labour leisure trade-off. The number of people on welfare will fall because workers leave part and full benefit dependence to qualify for the in-work tax credit.

Whether labour supply on net actually increases or decreases depends on the relative numbers of individuals at different points on the budget constraint working full-time, not working and working part-time and on the magnitudes of their responses. Some will stay as they are working full-time, not working and working part-time.

To summarise, the static labour–leisure trade-off model of labour supply suggests that increases in either benefit abatement thresholds or a reduction in benefit abatement rates will increase the numbers entering the benefit and see none leave. No one will leave.

A hours worked per week based in-work tax credit will move people who are not working and working a low number of hours to work and into a higher number of work hours respectively, with bunching around the eligibility point. An in-work tax credit will also cause some to cut back their hours so the net labour supply effect is ambiguous.

The net fiscal cost of an in-work tax credit depends on the phase-in and phased out particulars of the tax credit programme and the increase in paid employment and the number of taxpaying workers as a result of the in-work tax credit. The Working for Families tax credits in New Zealand and the United Kingdom are famous for clustering of labour supply around the eligibility point for the in work tax credit.

For example, in the UK, a lot of people used to work exactly 24 hours week. When the eligibility point was reduced to 16 per week, a new word had to be invented. This new word was mini-jobs to describe the large number of part-time workers in the UK who cut-back to exactly 16 hours per week. The family tax credit for workers is twice as generous in the UK as in New Zealand.

The blogs so far

part-one-the-labour-leisure-trade-off-and-the-rewards-for-working

part-two-the-labour-supply-effects-of-welfare-benefit-abatement-rate-changes

part-3-abatement-free-income-thresholds-and-labour-supply

part-4-in-work-tax-credits-and-labour-supply

part-5-higher-abatement-rates-and-labour-supply

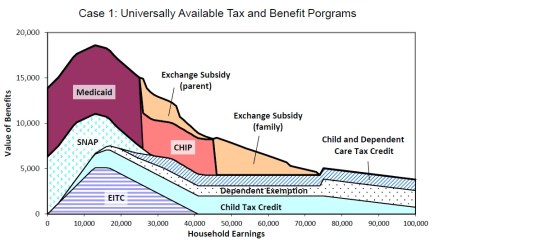

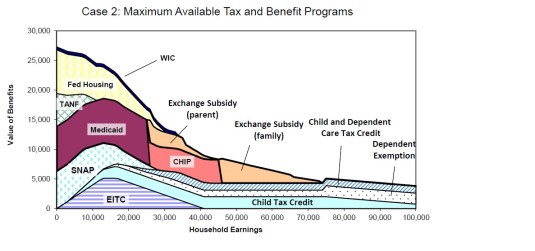

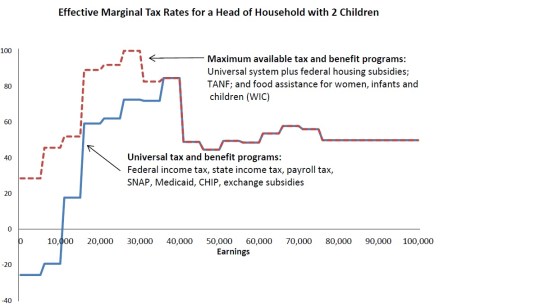

The shape of the welfare state in the USA

08 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in fiscal policy, income redistribution, labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA, public economics, welfare reform Tags: effective marginal tax rates, Obama care, poverty traps, welfare reform

One in five Americans on Medicaid; this image does not include those on Medicare –those over 65 who get their healthcare paid by the government.

It’s not just Ed Miliband. Labour’s on the wrong side of history » The Spectator

21 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, election campaigns, liberalism, macroeconomics, Marxist economics, political change, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics, technological progress Tags: free trade, globalisation, market augmenting governments

Politicians can’t be heroes any more. Instead, they have to operate within the tightly drawn tramlines of the global economy.

This is true for those on the left and the right, but the pressure that this places on countries to adopt a low-tax, light-regulation regime is something with which the right is far more comfortable.

via It’s not just Ed Miliband. Labour’s on the wrong side of history » The Spectator.

Net and average tax in NZ | Kiwiblog

17 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

Tax Burdens: Some Facts (For a Change) | Pundit 2011

16 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in income redistribution, liberalism, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, public economics Tags: tax burdens, tax incidence

The 47% is bigger than you think

16 Nov 2014 2 Comments

in politics - USA, public economics, Rawls and Nozick Tags: 47%, tax incidence, who pays taxes

What if We’re Looking at Inequality the Wrong Way? – NYTimes.com

16 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, entrepreneurship, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, liberalism, Marxist economics, occupational choice, politics - USA, poverty and inequality, public economics, Rawls and Nozick, technological progress Tags: Piketty, poverty and inequality

Recent Comments