It is not smart to subsidise electric cars

23 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in energy economics, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, transport economics Tags: carbon credits, carbon trading, electic cars

London Smog 1959

23 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, environmental economics, environmentalism Tags: London, London smog

On burden of proof

20 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, liberalism, rentseeking Tags: climate alarmism, conjecture and refutation, green rent seeking, philosophy of science, precautionary principle

Why masterly inactivity will be the American response to global warming

20 Mar 2015 1 Comment

in energy economics, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, Public Choice Tags: climate alarmism, global warming, green rent seeking, opinion polls, voting

The bandwagon effect

06 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming Tags: climate alarmism, conjecture and refutation, philosophy of science

Obama’s climate deal with China is a solar and wind energy fantasy

03 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in energy economics, entrepreneurship, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming Tags: carbon neutral economy, China, climate alarmism, global warming, solar energy

David Friedman on global warming, population and problems with the externality argument

02 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, David Friedman, economic history, economics of information, economics of regulation, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, law and economics, population economics, property rights Tags: climate alarmism, competition as a discovery procedure, David Friedman, externalities, global warming, population bomb, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

The loaded question

28 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, liberalism Tags: climate alarmism, conjecture and refutation, green rent seeking, philosophy of science, precautionary principle

On ad hominem attacks

26 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in development economics, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming Tags: activists, climate alarmism, conjecture and refutation, green rent seeking, philosophy of science, precautionary principle

On arguments from authority

22 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, liberalism, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: climate alarmism, conjecture and refutation, philosophy of science

Why did environmentalists change her mind about pollution taxes being a ‘licence to pollute’?

18 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in energy economics, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming

When I was a lad, the environmental movement was dead set against pollution taxes. Robert N. Stavins and Bradley W. Whitehead said in 1992:

…for many years, market-based incentives were characterized by environmentalists, not only as impractical, but also as “licenses to pollute.” Over time, environmental groups have frequently applied a different and more rigorous standard in measuring market-based systems against their command-and-control counterparts, possibly because of their belief that market-based systems legitimize pollution by purporting to sell the right to pollute. This old suspicion likely continues among many rank-and-file environmentalists.

How times have changed. Now the environmental movement of the biggest champions of carbon taxes as well as carbon trading. What gives? Anything more than cynical political opportunism? Concede nothing until the last moment when it is tactically opportune to sideline opposition.

Initially, all environmental regulations were command and control regulations that specified quantities and the technologies to be mandated and gave no role to prices to ensure that the pollution reduction was done by those who could do it cheapest. Robert Crandall noticed the shift in position in his recent essay on pollution controls:

… environmentalists have increasingly realized that markets can work to allocate pollution reduction responsibilities efficiently among firms and across industries. Although the command-and-control approach is still the norm, environmental lobbyists and legislators have, on occasion, considered market-based approaches to pollution control. Most of the proposals for limiting global warming, for example, explicitly include market-based approaches for controlling carbon dioxide emissions.

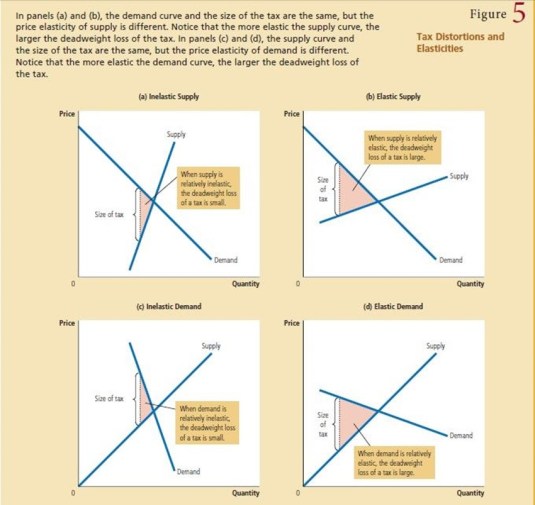

The reason for the change in tactics by the environmental movement is quite straightforward. The deadweight cost of regulation and taxes that leads to increasing resistance from those subject to existing and proposed environmental regulations.

- The deadweight losses of taxes, transfers and regulation are a constraint on inefficient policies (Becker 1983, 1985; Peltzman 1989).

- The deadweight loss is the difference between winner’s gain less the loser’s losses from a tax or regulation-induced change in output. Changes in behaviour due to taxes and regulation reduce output and investment.

- Policies that significantly cut the total wealth available for distribution by governments are avoided because they reduce the payoff from taxes and regulation relative to the germane counter-factual, which are other even costlier modes of redistribution (Becker 1983, 1985).

The rising deadweight cost of regulation due to technological change, and the dissipation of wealth through these rising costs progressively enfeebled environmental groups lobbying for more regulation. This allowed industry and consumers to win the initiative in resisting more environmental regulation. The cost of reducing carbon emissions is a classic example. Another is the United States acid rain allowance market.

In the case of carbon emissions, the additional political pressure that the winners had to exert to keep the same reduction in carbon emissions had to overcome rising pressure from the losers such as carbon intensive industries and they consist customers to escape their escalating losses of complying with any sort of further carbon emission regulation.

Eventually, the fight was no longer worthwhile relative to the alternatives. Taxed, regulated and subsidised groups can find common ground in wealth enhancing policies and an encompassing interest in mitigating any reduction in wealth from public policies (Becker 1983, 1985; Peltzman 1989).

In the case of global warming, both the environmental movement, and carbon intensive industries, and consumers find common ground in finding a cheaper way of reducing carbon emissions. That is done by agreeing to either carbon trading or carbon taxes. Coalitions of environmentalists and industry also form where carbon emission taxes or trading disadvantage the competition of some industries and some competitors within the same industry.

Carbon trading was a classic example of these dark coalitions. There’s a big difference in their cost to industry depending on whether carbon trading quotas are auctioned or given away to the incumbent firms for free or at a discount price.

It’s not easy to be green: the cost of fossil fuels divestments to the New Zealand superannuation fund

17 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of bureaucracy, energy economics, environmental economics, environmentalism, financial economics, global warming, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: efficient market hypothesis, fossil fuel disinvestment, Global disinvestment day, Green Party of New Zealand, index linked investing, privatisation, state ownership

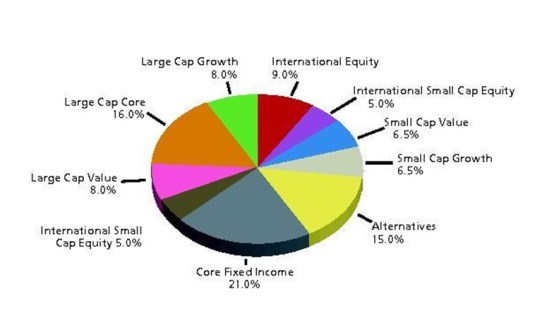

The Green Party of New Zealand wants the New Zealand superannuation fund to sell its $676 million in fossil fuel investments. For those not in the know, this government investment fund is worth about $25 billion and is funded by present taxes to pay for the universal old age pension in New Zealand. Its current investment strategy seems to rely heavily on index linked funds that minimise management and trading costs.

The Government uses the Fund to save now in order to help pay for the future cost of providing universal superannuation.

In this way the Fund helps smooth the cost of superannuation between today’s taxpayers and future generations.

In common with the endowment funds of the American universities, that $676 million is about 2% of the total New Zealand superannuation portfolio of about NZ$25 billion.

Any portfolio manager risks considerable fees if she must monitor the entire portfolio because 2% is of dubious moral stature.

The main cost of divestiture is compliance costs to prevent fossil fuel investments drifting back into the portfolio through the routine day to day investments of other companies within their portfolios as these other firms expand into new businesses or diversified. The entire portfolio must be monitored for this risk.

American universities found that fossil fuels divestment rules out indexed linked funds as a class, along with their low management and trading fees. Ethical investors must move to actively managed investment funds which are perhaps a third more expensive in management fees.

If a move to a fossil fuel free portfolio rules out passive indexed linked funds, that is a major risk to future returns of the New Zealand superannuation fund. Would this fossil fuels disinvestment including selling the recently acquired Z petrol station network by the New Zealand superannuation fund?

Z Energy now owns and manages these businesses, which include:

- a 15.4 per cent stake in Refining NZ who runs New Zealand’s only oil refinery.

- a 25 per cent stake in Loyalty New Zealand who run Fly Buys

- over 200 service stations

- about 90 truck stops

- pipelines, terminals and bulk storage

As usual, in the course of argument for disinvestment by the government investment fund, the Green Party makes an excellent argument for the privatisation not only of state owned enterprises but of the New Zealand superannuation fund.

Rather than have one victory at a time, the Greens want the NZ superannuation fund to use the funds from the disinvestment to reinvest in pet projects of politicians. The green party co-leader said:

Money released from divestment can be reinvested in the rapidly growing renewable energy and energy efficiency sectors, helping to hasten the transition of our economy to a low-carbon future.

This makes government investment funds the playthings of politicians so they can never match the returns of a genuinely privately owned investment fund.

I, Pencil versus Global Disinvestment Day in fossil fuels

16 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, environmentalism, theory of the firm Tags: activists, CEO pay, Global disinvestment day, global warming, separation of ownership and control

I, Pencil is a 1958 classic economics polemic by Leonard Read explaining about how nobody knows how even the most basic items in a consumer society are made and more importantly, they don’t need to know.

The relevance of I, Pencil to environmental activists on Global Disinvestment Day is they pretend to know enough about the vast number of products made by the many companies within the average share portfolio to be out of work out whether these companies are investing in fossil fuels so they can sell their shares in them.

I, Pencil made the point that people simply don’t know how the most basic products are made, much less who made them, and with what. Even if they did know, this information would become rapidly out of date. The marvel of the market is the remarkably small amount of information that people need to go about their business. Prices summarise much of what people need to know.

The whole point of the separation of ownership and control in modern corporations such as those listed on share markets is shareholders simply have no chance of monitoring the day to day affairs of companies in which they invest.

Many shareholders have too small a stake to gain from monitoring managerial effort, employee performance, capital budgets, the control of costs and investment policies (Manne 1965; Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Williamson 1985; Jensen and Meckling 1976). This lack of interest by small and diversified investors does not undo the status of the firm as a competitive investment.

Day-to-day management and risk bearing are split into separate tasks with various governance structures developed to ensure that the professional management teams serve the interests of the owners who invested in the company, along with their many other investments that compete for their attention. Large firms are run by managers hired by diversified owners because this outcome is the most profitable form of organisation to raise capital and then find the managerial talent to put this pool of capital to its most profitable uses (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b, 1985; Demsetz and Lehn 1985; Alchian and Woodward 1987, 1988).

Firms who are not alert enough to develop cost effective solutions to incentive conflicts and misalignments will not grow to displace rival forms of corporate organisation and methods of raising equity capital and loans, allocating legal liability, diversifying risk, organising production, replacing less able management teams, and monitoring and rewarding employees (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Fama 1980; Alchian 1950).

Indeed, our friends on the Left do go on about the power of boards of directors to set their own exorbitant salaries because shareholders lack of control them because they know so little about what they do.

That is, according to our friends on the Green Left, shareholders are not supposed to know enough about company performance and operations to work out if the salaries of top executives are justified. Top executive pay is always published in annual reports of companies.

Activist shareholders concerned about fossil fuel use nonetheless will be able to work out what the companies in their share portfolios are investing in and whether these investments are in fossil fuels. Details of these investments are much less public than the pay of top executives.

This continuous monitoring of corporate investment policies and associated buying and selling of shares will make investing in small parcels of shares in smaller companies listed on the share market rather expensive. Diversified share portfolios in index linked funds can have hundreds of companies in them. Some of these companies receive next to no media coverage that will simplify the cost to activist shareholders of monitoring their investments in fossil fuels.

Recent Comments