Milton Friedman on the essence of the Age of the Worker

13 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economic growth, economic history, health and safety, income redistribution, industrial organisation, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, occupational choice, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, Public Choice, rentseeking, unions Tags: competition and monopoly, The Great Enrichment, union power, union wage premium

Milton Friedman on evidence-based policy

27 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, Milton Friedman Tags: evidence-based policy, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge, unintended consequences

Milton Friedman vs. an Academic Socialist

08 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in Milton Friedman Tags: capitalism and freedom

The three lags on monetary policy

31 Mar 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, economics of information, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: lags on monetary policy, monetary policy

There are large uncertainties about the size and timing of responses to changes in monetary policy. There is a close and regular relationship between the quantity of money and nominal income and prices over the years. However, the same relation is much looser from month to month, quarter to quarter and even year to year. Monetary changes take time to affect the economy and this time delay is itself highly variable. The lags on monetary policy are three in all:

- The lag between the need for action and the recognition of this need (the recognition lag)

-

The lag between recognition and the taking of action (the legislation lag)

-

the lag between action and its effects (the implementation lag)

These delays mean that is it difficult to ascertain whether the effects of monetary policy changes in the recent past have finished taking effect.

Secondly, it is difficult to ascertain when proposed changes in monetary policy will take effect. Thirdly, feedbacks must be assessed. The magnitude of the monetary adjustment necessary to deal with the problem at hand is never obvious.

It is common for a central bank to act incrementally. The central bank makes small adjustments to monetary conditions over time as more information is available on the state of the economy and forecasts are updated.

Most discussions on monetary policy focus on the implementation lag. This lag depends on the fundamental characteristics of the economy.

A long and variable implementation lag means that it is difficult for central banks to ascertain what is happening now or forecast what will happen. Central banks may stimulate the economy after it is well on the way to recovery and tighten monetary policy when the economy is already going into a recession.

In his classic A Program for Monetary Stability, published in 1959, Milton Friedman summarised his empirical findings on length and variability of the lags on monetary policy:

on the average of 18 cycles, peaks in the rate of change in the stock of money tend to preceded peaks in general business by about 16 months and troughs in the rate of change in the stock of money to precede troughs in general business by about 12 months. For individual cycles, the recorded lead has varied between 6 and 29 months at peaks and between 4 and 22 months at troughs.

With lags as variable as those estimated by Friedman, it is difficult to see how any policy maker could know which direction to adjust his policy, much less the precise magnitude needed. Long lags greatly complicate good forecasting. A forecaster cannot know what the state of the economy will be when his policy takes effect.

Many Keynesians, Friedman notes, advocate “leaning against the wind.” By this they mean, in some sense, that the monetary (and fiscal) authorities should try to balance out the private sector’s excesses rather than passively hope that it adjusts on its own.

Friedman tested the Fed’s success at leaning “against the wind” by checking whether the rate of money growth has truly been lower during expansions and higher during contractions. He admits that this method of grading he Fed’s performance is open to criticism, but decides to go ahead and see what turns up. He finds that Fed has – for the periods surveyed – been unsuccessful.

By this criterion, for eight peacetime reference cycles from March 1919 to April 1958. Actual policy was in the ‘right’ direction in 155 months, in the ‘wrong’ direction in 226 months; so actual policy was ‘better’ than the [constant 4% rate of money growth] rule in 41% of the months.

Nor is the objection that the inter-war period biased his study is good since Friedman found that:

For the period after World War II alone, the results were only slightly more favourable to actual policy according to this criterion: policy was in the ‘right’ direction in 71 months, in the ‘wrong’ direct in 79 months, so actual policy was better than the rule in 47% of the months. [2]

One of the best ways to parry a metaphor is with another metaphor. Keynesians have a host of metaphors in their rhetorical arsenal; one frequently voiced is that a wise government should “lean against the wind” when choosing policy. Friedman counters:

We seldom know which way the economic wind is blowing until several months after the event, yet to be effective, we need to know which way the wind is going to be blowing when the measures we take now will be effective, itself a variable date that may be a half year or a year or two from now. Leaning today against next year’s wind is hardly an easy task in the present state of meteorology.

By scrutinising the practice of monetary policy over the decades, Friedman manages to produce objections that both Keynesians and non-Keynesians must take seriously. A key part of any response to Friedman rests on the ability of forecasters to do their jobs with tolerable accuracy.

The Tobin tax or @RobinHoodTax makes those monetary cranks in the social credit movement look credible!

31 Mar 2015 1 Comment

in macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetary economics Tags: monetary cranks, Robin Hood tax, Tobin tax

The Case for a RobinHoodTax.org on Financial Transactions goo.gl/sbL2JL #RobinHoodTaxUSA #RHT300B http://t.co/4lTAe1OMcU—

Robin Hood Tax (@RobinHoodTax) August 07, 2015

Sweden led the way with Tobin taxes in 1986: a 0.5% tax on the purchase or sale of an equity security. The revenues from the Tobin tax were initially expected to be 1,500 million Swedish kronor per year.

The actual revenues collected did not amount to more than 80 million Swedish kronor in any year and the average was closer to 50 million. Bond trading fell by more than 80 percent and the options market died. A lesson never learned by Tobin tax advocates. As taxable trading volumes fell, so did revenues from capital gains taxes, entirely offsetting the revenues from the equity transactions tax.

During the first week of the Swedish tax, the volume of bond trading fell by 85%; futures trading fell by 98%; and the options trading market disappeared. Trading for over 50% of Swedish equities moved to London by 1990. A true Robin Hood tax: the Tobin tax robbed from the Swedish capital gains taxman and gave to the British stamp duty taxman.

The Tobin tax is named after U.S. economist James Tobin who in 1972 suggested taxing foreign-exchange trades to limit currency speculation.

The Tobin tax on foreign-exchange transactions was to provide a disincentive for traders to make so many international transfers of money. Tobin in 1978 wrote that currency speculation can have ‘serious and painful internal economic consequences’. Tobin said his Tobin tax idea was unfeasible in practice.

Tobin and his idea of taxing of currency speculation improves market efficiency is total nonsense in theory as Milton Friedman explained:

The empirical generalization about the prevalence of destabilizing speculation, which is what gives the theoretical proposition its interest, seems to be one of those propositions that has gained currency the way a rumour does— each man believes it because the next man does, and despite the absence of any substantial body of well documented evidence for it.

Is the Tobin tax designed to raise 35 billion euros in revenue, as promised by EU Tax Commissioner Algirdas Semeta, or is it designed to curb speculation as was the original motivation by James Tobin to propose this tax?

Many have extolled such a tax as a potential source of earmarked revenues for a variety of purposes. Both left-wing and right wing populists have advocated the Tobin tax or Robin Hood tax to replace existing taxes or raise additional revenue.

Both types of populist advocate replacing or augmenting the income tax with a stamp duty. Enough people are familiar when stamp duties to realise that such a tax won’t raise much revenue. But if you call the stamp duty a Robin Hood tax, the media release suspends critical judgement and cheers them on.

Advocates of the Robin Hood tax blithely assert that the revenue raised will approximately equal 0.5% of the existing share and foreign exchange market turnover with few changes in behaviour or speculative activity, despite the imposition of a tax designed to curb speculation and reduce the total number of transactions significantly.

The $3.7 trillion-a-year Eurobond market came into being after JFK imposed an interest-equalization tax in 1963 to reduce investment in foreign securities by U.S. investors and to ease a so called balance of payments deficit.

What is the point of a Tobin tax if you already have a capital gains tax?. New Zealand doesn’t have a capital gains tax but it does have a tax on assets bought with the intention of resale rather than long-term income.

Why do share markets fall after the announcement of a Tobin tax? Trading in a more stable market should be value enhancing and increase share prices? Ditto exporters and more stable currency prices etc.? Exporter share prices should increase because of less need to hedge? Numerous studies find a significant reduction in equity turnover following a stamp duty introduction.

I am sure that with the City of London as a global financial centre, the British are cheering on efforts of other EU members to sabotage their own financial markets with a Tobin tax. FX turnover in the City of London reached over $1.8 trillion every day in 2010, accounting for 36.7% of the global total. About half of European investment banking activity is conducted through London.

Ed Prescott estimates a large quantity of intermediated borrowing-lending between households – several times GDP. A large amount of resources is used in this intermediation – a conservative estimate is 4% of GNP.

Prescott also argued that the cost of transferring financial assets has fallen dramatically – from 2% towards zero on Vanguards Indexed ETF. The spread between borrowing and lending by households down – the spread on home mortgages was 3% in 1960s – now about 2%. None of these trends bode well for either a large tax base or growing tax base.

Another way to think about a Tobin tax is to consider it to be a tax on ATM withdrawals. There was such a debits tax on bank withdrawals of $.20 in my home State of Tasmania in the 1980s.

Naturally, a Tobin tax on ATM withdrawals is not a tax on any sort of real economic activity. People would simply make fewer ATM withdrawals and look for other ways to not use ATMs. It is routine for cash balances to respond to the time and other costs of replenishing money balances, and the fixed cost of using deposits for purchases.

The most important aspect of monetary strategy is timing

28 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic growth, economics of information, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics, Robert E. Lucas Tags: Keynesian macroeconomics, lags on monetary policy, monetary policy

The simplest statement to make about the lags in monetary policy is they are long and variable. This simple statement is also the key insight to understanding the actual implementation of monetary policy. Hence, how many months or years in advance must a central bank forecast to achieve its monetary goals? In 1994, the Economist said:

But [central banks] cannot afford to wait until inflation is actually rising before they act. Monetary policy does not change the speed of the economy instantly: it can take 18 months or more for a rise in interest rates to have its full impact on inflation. The target of policy ought therefore to be future not current inflation, in order to prevent a surge in 1996. The earlier interest rates are raised, the better the chances of engineering a smooth slowdown to a sustainable rate of growth before slack in the economy is exhausted.

Economists differ about the length of those lags. Uncertainty about the average length of those lags and the variability of those lags makes discretion most difficult. Activist policy can improve welfare only if the information about economic structure and economists’ ability to forecast is sufficiently accurate.

Friedman is the most famous and persuasive critic of Keynesianism on the grounds of lags. He has two main arguments: first, that there are “long and variable lags” between the identification of a problem and the effects of the designed remedy; second, that activist policy often itself becomes a source of instability since policy itself becomes a variable that the market must guess.

Friedman’s critique does not depend on the quantity theory of money. Keynesian policies do not necessarily follow even if the Keynesian theory of the business cycle were conclusively proved.

It must also be demonstrated that the government has the ability and willingness of the government to act as the theory prescribes. We are therefore further assuming that central banks have the incentive to stabilise the economy. If the government lacks the information required to stabilise the economy, issues of public choice incentives become fully redundant. Incentives to pursue an objective do not matter if the objective itself is unattainable.

Competing visions of central banking

25 Mar 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, economic growth, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics, Robert E. Lucas Tags: Keynesian macroeconomics, monetary policy

The competing visions of central banks over monetary policy have been defined by Franco Modiglani and Milton Friedman respectively. Modiglani considers the Keynesian vision of macroeconomic policy to be:

a market economy is subject to fluctuations which need to be corrected, can be corrected, and therefore should be corrected.

The Keynesian claim implies that central banks have sufficient knowledge of the structure of the economy to be able to choose the policy mix appropriate to a given set of circumstances. It is possible to target unemployment, interest rates and inflation in such a way that they can be maintained (and hence made predictable) by constant adjustment of policy instruments to new shocks.

The Keynesian approach assumes that the economy can slip into recessions for all sorts of reasons (Barro 1989). Business fluctuations result from shocks to aggregate demand. The principal source of these shocks are expectations induced shifts in investment demand. The role of the central bank is to make prompt, frequent policy responses to counteract this instability.

The task of government is to discover the particular monetary and fiscal polices which can eliminate shocks emanating from the private sector. A key finding of recent macroeconomic research is that anticipated monetary policy has very different effects to unanticipated monetary policy.

The Keynesian vision thus presuppose that government can foresee shocks which are invisible to the private sector but at the same time it is unable to reveal this advance information in a credible way and hence defusing the shock because it is no longer unanticipated. In addition, the counter cyclical monetary policies of governments must themselves be unforeseeable by private agents, but at the same time systematically related to the state of the economy (Lucas and Sargent 1979)

Of course, the Keynesian view of central banking is also premised on a goodwill theory of government. Governments pursue policies that are in the public interest. That is a public interest that is well-defined and is free of conflicts over income distribution, electoral success and power the could lead policy-makers to pursue goals other than full employment, stable prices and efficiency. Thus, if the latest forecast is a recession, additional stimulus is the usual prescription. However, since most Keynesian economists accept the permanent income and natural rate hypotheses, more stimulus implies less later at some unknown time.

Friedman’s vision of central banking is far more circumspect:

The central problem is not designing a highly sensitive [monetary] instrument that offsets instability introduced by other factors[in the economy], but preventing monetary arrangements becoming a primary source of instability (Milton Friedman 1959).

Friedman considers that a key element in the case for policy discretion is whether the sufficient information is available that can be used to reduce variability and assist the economy’s adjustment the unforeseen. A well intentioned policy-maker will destabilise if he is mislead by incomplete or incorrect information.

From the monetarist standpoint, price stability can be approximately attained under a well chosen and predictable monetary policy rule. Under this view, the unemployment and interest rates are unpredictable and can manipulated only at a prohibitive cost. The Keynesian and monetarist views are mutually incompatible and lead to very different policy recommendations (Lucas 1981).

Paul Samuelson on where he disagreed with Milton Friedman on macroeconomic policy

19 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, fiscal policy, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: fiscal policy, monetary policy, Paul Samuelson, rules versus discretion, stabilisation policy

via Samuelson vs. Friedman, David Henderson | EconLog | Library of Economics and Liberty and An Interview With Paul Samuelson, Part One — The Atlantic.

After reading the annual reports of the Fed, Milton Friedman noticed the following pattern

16 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, great depression, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: lags on monetary policy, monetary policy

Finn Kydland on the myth of the Celtic Tiger

14 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic growth, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman

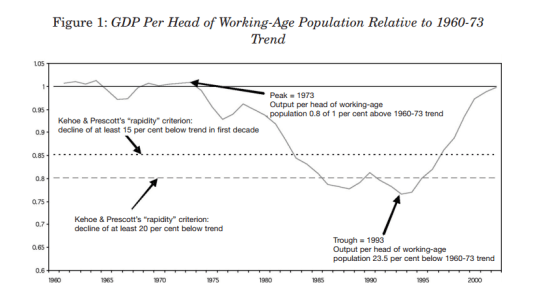

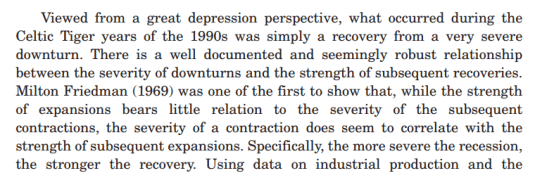

Finn Kydland has a simple explanation for the so-called Celtic Tiger. It was a recovery from a deep depression in the 1970s and 1980s in the Irish economy.

HT: “Ireland’s Great Depression,” Finn Kydland, Alan Ahearne and Mark A. Wynne, The Economic and Social Review 37(2), Summer/Autumn 2006, 215-243. (pdf)

Recent Comments