David Friedman on global warming, population and problems with the externality argument

02 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, David Friedman, economic history, economics of information, economics of regulation, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, law and economics, population economics, property rights Tags: climate alarmism, competition as a discovery procedure, David Friedman, externalities, global warming, population bomb, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Richard Posner on libertarian scepticism about law as an engine of women’s liberation

25 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

The argument for liberty is not an argument against organization

08 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in Austrian economics, F.A. Hayek, liberalism Tags: The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Why Can’t Public Transit Be Free? – The Atlantic

01 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, transport economics Tags: activists, do gooders, free public transport, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

The earliest urban experiment in free public transit took place in Rome in the early 1970s. The city, plagued by unbearable traffic congestion, tried making its public buses free.

At first, many passengers were confused: “There must be a trick,” a 62-year-old Roman carpenter told The New York Times as he boarded one bus. Then riders grew irritable. One “woman commuter” predicted that “swarms of kids and mixed-up people will ride around all day just because it doesn’t cost anything.”

Romans couldn’t be bothered to ditch their cars—the buses were only half-full during the mid-day rush hour, “when hundreds of thousands battle their way home for a plate of spaghetti.” Six months after the failed, costly experiment, a cash-strapped Rome reinstated its fare system.

Three similar experiments in the U.S.—in Denver, Colorado, and Trenton, New Jersey, in the late 70s, and in Austin, Texas, around 1990—also proved unfruitful and shaped the way American policy makers viewed the question of free public transit.

All three were attempts to coax commuters out of their cars and onto subway platforms and buses. While they succeeded in increasing ridership, the new riders they brought in were people who were already walking or biking to work. For that reason, they were seen as failures.

A 2002 report released by the National Center for Transportation Research indicated that the lack of fares attracted hordes of young people, who brought with them a culture of vandalism, graffiti, and bad behavior—which all necessitated costly maintenance. The lure of “free,” the report implied, attracted the “wrong” crowd—the “right” crowd, of course, being wealthier people with cars, who aren’t very sensitive to price changes.

HT: http://m.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/01/why-cant-public-transit-be-free/384929/

Robert D. Tollison on the main positive contribution of economists to public policy

30 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

The Times of London on the fatal conceit, the pretence to knowledge and unintended consequences

27 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

The competing visions of stabilisation policy have been defined by Franco Modigliani and Milton Friedman

26 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economics of information, history of economic thought, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: Franco Modigliani, Keynes in macroeconomics, monetary policy, stabilisation policy, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Paul Samuelson and Robert Lucas both agree that economists have solved the problem of economic depressions

24 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, fiscal policy, great depression, great recession, history of economic thought, macroeconomics, monetary economics, Robert E. Lucas Tags: Paul Samuelson, prosperity and depression, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Paul Samuelson’s repeated predictions of the Soviet Union economy catching up with the USA

24 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in economic history, economics of bureaucracy, growth disasters, Marxist economics Tags: fall of communism, fall of the USSR, forecasting errors, Paul Samuelson, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

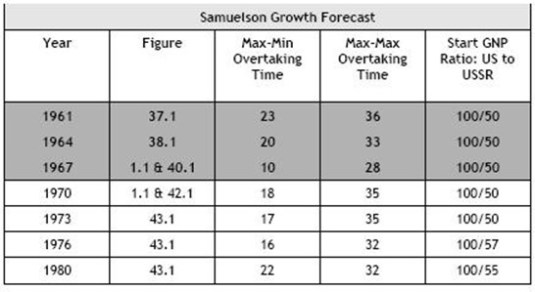

Paul Samuelson wrote in the 1961 edition of his famous economics textbook that GNP in the Soviet Union was about half that in the United States but the Soviet Union was growing faster.

Figure 1: Samuelson’s 1961 Forecast of Soviet catch up

Source: Levy and Peart (2006)

As a result, Soviet GNP would exceed that of the United States by as early as 1984 or perhaps by as late as 1997, depending on whether you were reading the early 1960s or later editions of Samuelson’s immensely popular textbook. In the 1980 edition there was little change in the analysis, though the two dates were delayed to 2002 and 2012

Samuelson predicted that the Soviet Union would catch up with the United States and kept predicting this until 1989 in every edition of his textbook of which there are at least 14. Levy and Peart were good enough to tabulate these predictions by Samuelsson of Soviet catch up with the USA over the editions of his textbook in the table below.

Source: Levy and Peart (2009)

Samuelson’s predictions of the Soviet Union catching up to and overtaking the United States were echoed in most other major economics textbooks of his time.

Plainly, they all got it wrong except for the Austrian economists, Eastern bloc émigrés and G. Warren Nutter.

From 1956 to 1961, Nutter undertook a massive study of the history of the economy of the Soviet Union and published The Growth of Industrial Production in the Soviet Union in 1962.

Nutter’s study concluded that Soviet economic growth over the first half of the 20th Century was indeed remarkable, and that there had been periods of growth spurts, but when the entire Soviet period was taken into consideration, Soviet growth lagged behind Western economies and Soviet economic capacity showed every sign of falling further behind rather than catching up with the West.

Nutter’s conclusions were certainly not welcomed by the Sovietologists of his time. As the fall of the Soviet Union revealed more realistic data, Nutter’s estimates of Soviet growth rates have been vindicated, and in fact, if anything Nutter overstated rather than understated Soviet economic performance.

Paul Craig Roberts found worse exaggeration with the Romanian economy in 1979. A World Bank report, Romania: The Industrialization of an Agrarian Economy under Socialist Planning, credited central planning with achieving a 9.8 annual rate of economic growth over the quarter century from 1950 to 1975. It should be added that in the 1970s, Romania was a western favourite because of its independent stance within the Eastern European bloc.

The World Bank did not realize that using these growth rates to project backward these growth figures on Romanian income per capita quickly produced a figure too low to sustain life. This mistake provoked the Wall Street Journal observation:

We have heard exaggerated claims made for central economic planning, but never that it resurrected a whole nation from the dead.

Samuelson never reflected in his later textbooks after 1989 about how wrong he was for many decades about Soviet economic performance. Few people, thank you for admitting that there you’re wrong – they are more likely to dance on the grave of your error.

In Paul Samuelson’s case, he had more reasons of most to learn from his failed predictions because as his predictions didn’t work out, he had to rewrite and update his book and charts predicting the USSR was going to overtake the USA in about 20 years.

Rather than the suspect that there something wrong with the Soviet economic system, Paul Samuelson looked for excuses – increasingly pathetic excuses. As Larry White explained:

In the seven editions of his textbook published from 1961 to 1980, Samuelson kept including a chart indicating that Soviet output was growing faster that U.S. output, and predicting a catch-up in about twenty-five years. He repeatedly had to move the predicted catch-up date forward from the previous edition because the gap had never actually begun to close. In several editions he blamed low realized Soviet growth on bad weather.

What is more puzzling is Samuelson did update his views on the merits of fiscal and monetary policy in stabilising the economy, and the effectiveness of each over the decades in light of experience and between the 1960s and 1980s. In the 1948 edition of his best-selling textbook, Economics, Samuelson wrote that:

few economists regard Federal Reserve monetary policy as a panacea for controlling the business cycle.

In 1967 Samuelson said that monetary policy had “an important influence” on total spending. His 1985 edition states;

“Money is the most powerful and useful tool that macroeconomic policymakers have,” adding that the Fed “is the most important factor” in making policy.

Samuelson’s 1967 edition said policymakers faced a trade-off between inflation and unemployment. His 1980 edition said there was less of a trade-off in the long run than in the short run. The 1985 edition, he said there is no long-run trade-off between unemployment and inflation.

Samuelson gave quite compelling reasons as to why Keynesianism declined:

- Keynesian macroeconomists and policymakers made the mistake of projecting the experience of the Great Depression onto the post-war era;

- it turned out that, contrary to what Keynes had said, monetary policy mattered a lot; and

- The final blow to Keynesianism was stagflation: There is nothing in Keynesian macroeconomics that would allow you to solve stagflation.

Samuelson did not learn in the same way from brute experience regarding the economics of socialism.

Via Why Were American Econ Textbooks So Pro-Soviet? Bryan Caplan | EconLog | Library of Economics and Liberty and Soviet Growth & American Textbooks.

Measurement without theory alert: It’s Time For Companies To Fire Their Human Resource Departments – Forbes

23 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics, theory of the firm Tags: agent principal problems, creative destruction, human resource departments, managerial discretion, measurement without theory, The pretence to knowledge

Kyle Smith in Forbes today launched into human resource departments and called for their abolition. My hypothesis is he doesn’t understand why rigid, rule-bound human resource departments exist in the first place in large hierarchies. The fact that this form of organisation survives in competition with other forms of organisation and modern human resource management has been spreading rather the contracting in popularity over the recent decades is a test of its survival value in market competition.

Smith made the following claims:

- 93 percent of the HR staffers deciding whether to call in someone for an interview were female, these tend to be young and single and hence still in the dating market for men so they’re jealous of beautiful women so they are less likely to call them in for an interviews because of their looks;

- They speak gibberish: “Internal action learning.” “Being more planful in my approach.” “Human capital analytics.” “Result driven”;

- HR employees are too absorbed in process and heedless of the big picture;

- HR departments grossly overestimate the extent to which employees will recommend the company to a friend; and

- HR places a disturbingly high premium on what it calls “communication skills”.

This is a classic example of measurement without theory. Of not having a theory to make sense of the facts and explain why this form of organisation – modern human resource departments – is survived and prospered in market competition.

The form of organisation that survives in competition with actual and potential market rivals is that specific form of organisation which allows the firm to deliver the products that customers want at the lowest price while covering costs (Alchian 1950; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b).

Some larger firms may struggle with striking the most profitable balance between greater local managerial discretion and effective corporate governance of a large diverse organisation with professional managers and diffuse ownership structures. It will be shown that very large firms promulgate rigid personnel policies while smaller firms are much more flexible in their deals with individual employees.

Competition between different sizes, shapes and internal organisational forms of firms all vying for sales, cheaper sources of supply and investor support sifts out the keener priced, lower cost, and more innovative enterprises (Alchian 1950; Stigler 1958). These lower-cost firms will be able to under-sell their higher cost rivals. The winning size and shape is that configuration which meets any and all problems the firm is actually facing and seizes more of the entrepreneurial opportunities that are within its grasp (Stigler 1958; Alchian 1950).

As the size of a firm grows, important information is less likely to find its way up hierarchies and reach the appropriate decision-makers and be up-to-date and be comprehended if it does. The top of corporate hierarchies can be overwhelmed with information and much of what information they do receive can be old, incomplete, conflicting and garbled (Williamson 1967, 1975).

Larger firm respond to this loss of up-to-date knowledge of the local circumstances of time and place with a greater dependence on broad rules (Oi 1983a, 1983b, 1988, 1990). For this reason, larger employers will be less effective in assessing individual attributes of employees and assigning employees to the most productive task (Parsons 1997).

Larger firms offset this competitive disadvantage by specialising in the production of standardised goods with larger teams of more homogeneous, more highly trained workers; smaller firms produce more customised goods produced in smaller quantities by smaller teams of less specialised employees (Oi 1983a, 1983b; Oi and Idson 1999). Smaller firms can quickly adapt to changing circumstances of all kinds because top management are closer to and better informed about all operations, employees and customers.

If large firms are to survive in competition, the personnel policies of larger employers must adapt to offset the diseconomies of scale in idiosyncratic decisions by relying on broad inflexible rules. These top-down rules will leave far less discretion in the hands of local managers. This is because the higher layers in a large corporate hierarchy cannot control and direct lower layers that behave in an increasing diversity of ways to the same information and to local events that do not affect the rest of the firm.

Planning and coordination costs increase with organisational size. There will be errors in assigning tasks, deciding rewards, and monitoring performance. Information flows and co-ordination become problems that only increase with the size if the firm. It can be cheaper to monitor compliance with rules and issue general instructions that apply to all employees.

Limits on the degree of local managerial discretion over employment relations in large managerial firms can arise from restrictions on managerial delegations, divided decision making rights, hierarchical approval procedures, and the breath and content of wage and personnel policies. The discretion of supervisors in large firms may be limited to individual performance ratings (Gibbs and Hendricks 2004). Some large firms may have no process or policy to handle requests for a phased retirement.

Good evidence to illustrate the proposition that larger firms prefer rigid rules over discretion in personnel policies comes from the days of mandatory retirement. Mandatory retirements can be viewed as the wholesale substitution of local managerial discretion with a single company-wide rule because larger firms find idiosyncratic decisions to be more costly (Parsons 1997).

Mandatory retirements are near universal in very large workplaces, but in small to medium size firms, there were flexible retirement polices. Few very large firms reported flexible retirement polices.

Smaller firms provided for policies that allowed for exceptions to mandatory retirement rules while most of largest firm reported a policy of zero exceptions to mandatory retirement rules (Parsons 1997). This U.S. evidence from the time of mandatory retirements suggests that larger employers may find it more difficult to handle the idiosyncrasies of phased retirements.

A price of growth in the size of firms is often the standardisation of products, workforce compositions and terms of employment. Standardisation in larger firms constrains wages, reduces managerial slack and aggrandisement, and facilitates performance evaluations and yardstick competition between divisions.

Large employers write personnel policies to govern most aspects of the employment relationship. These human resources policies will be common to all employees and all revisions and exceptions require central approval.

More centralised human resources policies that limit supervisor discretion can reduce favouritism and the cost of employees wasting working time on attempts to influence line managers about their pay and working hours.

The price of more centralised human resources policies is less local adaptability to genuine opportunities. The offset is centralised personnel policies save on the costs to the firm of having to gather and process up and back down a large corporate hierarchy the information need to make decisions with more localised finesse. These rule-bound decisions are less deft but are also cheaper to make.

In other areas, large firms will take steps to empower local managers and foil ill-informed intervention from above to put decisions where the knowledge is held. Reporting and decision procedures and performance pay can all craft a sufficient amount of distance between managerial layers to create an adequate amount delegation to take advantage of local knowledge and overcome the costs of slow and garbled information transfer in hierarchies, managerial overload, and the losses from decisions lagging behind in dynamic and unpredictable environments.

Smaller firms survive and profit from being small because their size allows them to succeed with more workforce diversity and more customised products. The owners are know more and can be directly involved in management. Owner-managers can quickly adapt to new conditions with fewer risks and can sidestep the need to develop policies on phased retirements or revise it on the spot in light of an unforeseen or low-probability contingency.

One reason for larger firms paying higher wages by industry standards is as compensation to offset their requirements for more standardised hours of work. The efforts of the more able entrepreneurs to deploy their talents wisely result in systematic differences in the organisation of production and the structure of the workforces that firms employ. Smaller employers pay less in wages but can offer more flexible work hours. The wage premiums offered in large firms are in part because of their organisational rigidity.

Rigid, rule-bound HR department is doing its job to the letter because this constrains line managers from favouritism and been lobbied for favours by employees was they have very little control over terms and conditions of employment and promotions and perhaps only have input into performance ratings.

A major reason why companies limit pay reviews and performance promotion rounds to an annual process is to prevent everyone wasting time between these annual events on lobbying for pay rises and promotions The HR department is the guardian of the gate to ensure there is no favouritism because it enforces rules rigidly.

The nub of the problem is large firms have several layers of management with fairly strict limits on what each individual line manager can do (Williamson 1975, 1985; Fama and Jensen 1983b). There must be some limits on local managerial discretion because the owners and senior managers of any firm set the strategic direction of the firm, the products it sells, and how many workers are employed and on what wages. All parts of the firm must march in the same direction.

The discovery of monitoring or incentive systems that induce managers to act in the best interest of shareholders are entrepreneurial opportunities for pure profit (Fama and Jensen 1983b, 1985; Alchian and Woodward 1987, 1988; Demsetz 1983, 1986; Demsetz and Lehn 1985; Demsetz and Villalonga 2001).

Investors will not entrust their funds to who are virtual strangers unless they expect to profit from a specialisation and a division of labour between asset management and managerial talent and in capital supply and residual risk bearing (Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). There are other investment formats that offer more predictable, more certain rate of returns.

One type of corporate waste is uncompetitive staff retention policies. The risks to dividends and capital because of this and other manifestations of corporate waste, reduced employee effort, and managerial slack and aggrandisement in large managerial firms are risks that are well known to investors (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jenson 1983b). Corporate waste and managerial slack also increase the chances of a decline in sales and even business failure because of product market competition (Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983b).

The reward for forming a well-disciplined managerial firm despite the drawbacks of diffuse ownership is the ability to raise large amounts in equity capital from investors seeking diversification and limited liability (Demsetz 1967; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983b; Demsetz and Lehn 1985).

Competition from other firms will force the evolution of devices within the firms that survive for the efficient monitoring the performance of the entire team of employees and of individual members of those teams as well as managers (Fama 1980, Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Demsetz and Lehn 1985).

Managerial firms who are not alert enough to develop cost effective solutions to incentive conflicts and misalignments will not grow to displace rival forms of corporate organisation and methods of raising equity capital and loans, allocating legal liability, diversifying risk, organising production, replacing less able management teams, and monitoring and rewarding employees (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Fama 1980; Alchian 1950).

Entrepreneurs will win profits from creating corporate governance structures that can credibly assure current and future investors that their interests are protected and their shares are likely to prosper (Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b, 1985; Demsetz 1986; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). Corporate governance is the set of control devices that are developed in response to conflicts of interest in a firm (Fama and Jensen 1983b).

A risk of greater local managerial discretion in a large firm is less effective governance (Williamson 1975, 1985; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b). The separation of decision management rights, vested in hired managers, from decision control rights, vested in the board of directors, is a common governance safeguard against conflicts of interest in business, professional and non-profit organisations, large and small (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b).

Decision management rights cover the initiation and the implementation of decisions. Decision control rights involve the ratification and the monitoring of decisions. Managers and division heads carry out the production decisions, budgets and policies on wages, hours, staffing and job designs developed by head office and which are ratified by the board of directors (Fama and Jensen 1983b, 1985).

Managerial firms survive in market competition because divided decision rights and limits on the local discretion of expert managers and corporate boards increase investment returns net of greater scope for managerial slack and the inflexibilities of growing hierarchies (Fama and Jensen 1983b; Demsetz and Lehl 1985; Alchian 1950). More local managerial discretion over conditions of employment and hours of work may strike at the heart of the governance structures that allow many large firms to emerge, survive and prosper despite their separation of ownership from control.

In contrast, entrepreneurial firms are owned and managed by the same people (Fama and Jensen 1983b). Mediocre personnel policies and sub-standard staff retention practices within entrepreneurial firms are disciplined by these errors in judgement by owner-managers feeding straight back into the returns on the capital that these owner-managers themselves invested. Owner-managers can learn quickly and can act faster in response the discovery of errors in judgement.

The owners of a managerial firm advance, withdraw, and redeploy capital, carry the residual investment risks of ownership and have the ultimate decision making rights over the fate of the firm (Klein 1999; Foss and Lien 2010; Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Owners of a managerial firm, by definition, will delegate control to expert managerial employees appointed by boards of directors elected by the shareholders (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b).

The owners of a managerial firm will incur costs in observing with considerable imprecision the actual efforts, due diligence, true motives and entrepreneurial shrewdness of the managers and directors they hired (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983b).

Poor cost control, budgetary excess and any lack of innovation and initiative over products designs and pricing, input mixes and wage and employment polices will reflect in relative divisional performances and overall corporate profits of a managerial firm.

Any news of less promising current and future net cash flows will feed into share prices and into the labour market prospects of both career managers and the members of boards of directors (Manne 1965; Fama 1969, 1970; Fama and French 2004; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Demsetz 1983; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). To survive, managerial firms must balance delegation with more centralised control (Fama and Jensen 1983a; McKenzie and Lee 1998).

Managerial firm have HR departments, and will continue to have HR departments because their objective is to limit the discretion of individual line managers and ensure that they carry out corporate objectives.

Smaller firms are more likely to be entrepreneurial firms where the owner-managers are on the spot to make the key decisions and keep things in line.

Recent Comments